Of all the city-states in Greece, Athens was the most fortunate. The city’s guardian was Athena, the goddess of war and wisdom. Indeed, the Athenians did well in war and were blessed with wisdom. In the dark days, when barbaric invaders had conquered one city after another, Athens had not surrendered. Later, when Athens felt the growing pains that brought civil war and ruin to so many city-states, a series of wise men guided Athenians safely through their troubles. The right leaders always seemed to come along at the right time.

It was more than good luck, ofcourse. The Athenians put their trust in men with new ideas and they were willing to experiment. The experiments changed an ordinary little town into a great brilliant polis that left an enduring mark on the world.

Athens was old. Its story began with a list of kings so ancient that no one was quite sure when they had lived. The greatest of them was Theseus, the young hero who killed the monster at Crete. The storytellers said that he won the friendship of the neighbouring tribesmen and persuaded their chiefs to swear loyalty to his city. That was the beginning of the polis, but many years passed before it became important.

In the seventh century B. C., Athens was only a second-rate, backwoods polis. Its king could do little more than dream of the glorious old days when their forefathers had defended the town’s acropolis – the Athenians called it the Rock – against the barbarians. Attica, the countryside around the old fortress on the Rock, was really ruled by a quarrelsome lot of rival noblemen, the chiefs of the clans. These barons ran their vast estates like private kingdoms. They owned the country villages and all but owned the people in them. They were constantly fighting one another and often they set fire to a rival baron’s fields, destroying a year’s crops in one day.

Something had to be done, for the endless little wars were driving Athens to starvation and ruin. The barons decided to change their ways. They joined forces, captured the Rock and set up a council to help govern the polis. They swore again the ancient oaths of loyalty to Athens and prayed to Athena to teach them to live together in peace.

The old quarrels, however, did not die so easily and new feuds broke out. The barons made life miserable for the common people, who hated them. The people themselves were divided. Those in the city and on the nearby farms, who called themselves “The Plain”, did not trust those by the sea, who called themselves “The Coast”.

To make things even worse, Athens had no written laws. The council of judges, the Areopagus, was a committee of barons and they changed the laws to suit themselves. When a baron claimed the land of a farmer who owed him money, the council always ruled in favour of the baron. If this still did not cover the debt, the council gave the baron permission to sell the farmer into slavery.

It happened that Athens had just begun to trade with money instead of exchanging goods. The barons were selling their crops abroad for cash and at home food became scarce. As prices went up, the farmers had to borrow to live. More and more of them lost their lands and their freedom. The people demanded laws to protect them, laws that would not be changed from one day to the next. In 621 B. C., the barons finally chose a man named Draco to write a code of laws for the city but, when the laws were posted, the citizens who rushed to read them turned away angrily. “Draco did not write these laws in ink!” they shouted. “he wrote them in blood!”

For Draco’s laws were strict, his punishments harsh. Even the theft of a fig from a baron’s orchard meant death. Draco was asked if he thought it was fair to give the same punishment to petty thieves and murderers. He answered, “Death is a proper punishment for the thief. It is unfortunate that nature has not given us a harsher one for a greater criminal.”

Solon the Wise

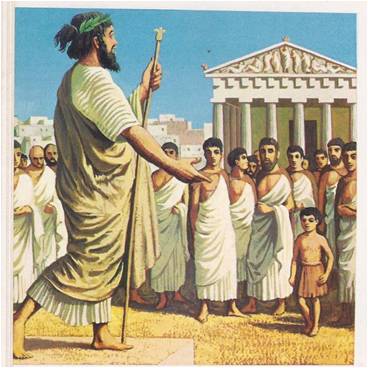

After that the people talked n more about laws. They talked about war against the barons. Both the people and the barons looked for a general to lead them and both turned to the same man – Solon. The barons chose him because he was a nobleman, a merchant’s son who understood business and money. The people chose him because he was a wise man, a poet who spoke out against injustice and agreed. Each side was sure that he would fight for them and each offered to make him the tyrant of Athens.

Again the Athenians were lucky. Solon had traveled widely and had seen for himself how civil wars destroyed cities. He said he would not be a tyrant or choose sides. If he could not work with both sides, he would work with neither. If they wanted him at all, they must agree to abide by the laws he made, whether they liked them or not. The spokesmen for the two sides looked at each other, nodded and accepted his terms.

In the first decree, Solon freed the farmers who had been made slaves and forbade the selling of citizens for their debts. He limited the amount of land that one man could own, so that the barons had to stop collecting little farms. Then he cancelled Draco’s laws and wrote a new code for Athens. When his laws were posted – first on wooden tablets, then on stone columns set up in the centre of the city – no one shouted that they were written in blood. The laws were sensible and fair. They set up a council of four hundred to guide the city and watch over the judges. Any citizen could be elected to the Council and every citizen had the right to vote in the Assembly.

Pisistratus

Solon seemed to have thought of everything. There was a law that made it easier for the farmers to plant profitable crops; a law that granted citizenship to foreign craftsmen who brought their business and families to Athens; a law that required every father to teach his son a trade. Competition among the men for rich wives was discouraged by a law that forbade a bride to have a dowry of more than three outfits of clothing and her kitchen pots. Another law said that ladies must not go out at night except in a chariot and a torchbearer running ahead. Any man whose dog bit another man was ordered by law to deliver the animal to the magistrates with a log, four and a half feet long, tied to its neck.

When his work was done, Solon left Athens for ten years. He wanted the Athenians to see that his laws would work for them whether he was in the city or not. His cousin, Pisistratus, had other ideas – he planned to make himself tyrant of Athens. He felt that his chances were good. He had become a hero when he had led the armies that won the island of Salamis for Athens. Since he had made a great point of speaking well of the common people, which added to his popularity. There were still a number of people who hated the barons. Besides some day the clans of the Plain and Coast would start to quarrel again and a new group had sprung up, the hill people. They were poor, they belonged to neither the Coast nor the Plain, they despised the barons and they needed a leader. The time would surely come when Pisistratus would be able to take advantage of these divisions and dissatisfactions; meanwhile, he waited.

He waited for ten years. Solon returned to Athens but he avoided politics and Pisistratus saw no reason to change his own plans. Just as he had foreseen, the clansmen were at it again. Megacles, the leader of the Coast, had insulted Lycurgus, the leader of the Plain. The people of the hills were now well organized and called themselves “The Hill”. Pisistratus thought most of them were rather stupid, but he needed them for fighting, not for thinking.

In 561 B. C., Pisistratus believed the time had come for him to act. One morning he raced his chariot into the crowded market place. As he reined his winded horses to a halt, the people saw that he was wounded. Staggering from the chariot, he pointed to his wound and gasped, “I have these because I spoke for the people!”

As a matter of fact, Pisistratus had made the wounds himself. They were shallow cuts, the kind that bleed a great deal but heal quickly. The people did not know that, ofcourse. They called for a special meeting of the Assembly, where they demanded protection for Pisistratus. Solon, who saw through his cousin’s trick, tried to tell the people the truth. They were too excited to listen and he lost his temper. “You are each so clever,” he cried. “How can you be so stupid when you get together?”

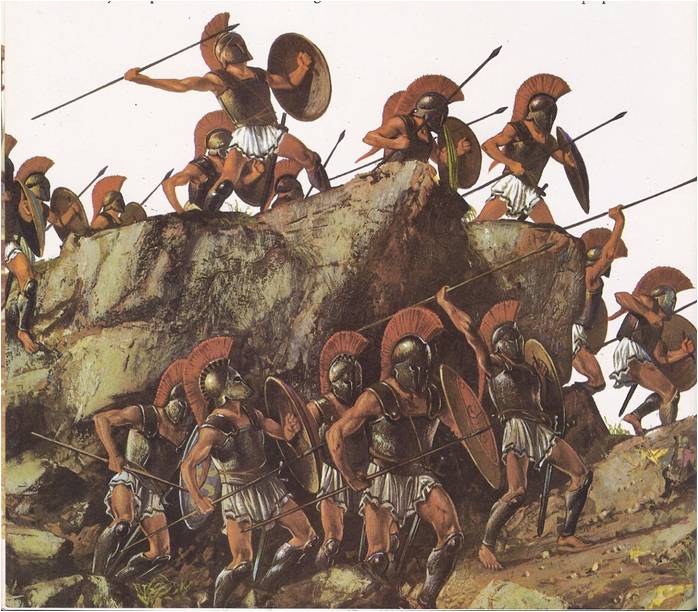

Stupid or not, the Assembly voted to give Pisistratus a bodyguard of fifty men with clubs. In the next few days, the bodyguard grew until it numbered close to a hundred men. They marched on the Acropolis and the hill people poured into the city to join the fight. The Acropolis was taken and suddenly Pisistratus was tyrant of Athens.

Athens’ New Tyrant

The barons who led the men of the Plain and the Coast patched up their quarrels and rushed to attack the Hill. Pisistratus was driven out, but the barons fell to arguing among themselves again. Megacles of the Coast became so angry that he switched sides and offered to help Pisistratus. There was one condition, however – Pisistratus must marry his daughter.

Pisistratus agreed and the two men worked out a wild scheme. The Greek historian Herodotus described it in this way:

“They put together the most ridiculous scheme that I imagine was ever thought of. I say that, first, because the Greeks have always been famous for their shrewdness; and second, because this trick was played on the Athenians, who are always said to be the cleverest of all Greeks. They found a woman called Phye (which means ‘tall’) who was nearly six feet tall and very beautiful, too. They dressed her in a suit of armour, rehearsed her in the part she was supposed to play and drove into the city. There the heralds, who had been sent ahead, cried, ‘Men of Athens, give kind welcome to Pisistratus. Athena honours him above all other men and has come to bring him to her own Acropolis.’ They shouted this about the city and the people, sure that the woman was the goddess, took back Pisistratus and paid worship to a girl from the country.”

Herodotus did not say what Solon did this time. Perhaps he simply stayed home in disgust. In any case, Pisistratus was tyrant again, but only for two years. When he married Megacles’ daughter, he refused to treat her as his wife or to pay any attention to her at all. Megacles was furious. He wanted to be the father-in-law of a tyrant and had hoped to be the grandfather of another. Instead, he and his daughter had been insulted. He properly organized Pisistratus’ old enemies, the clans and the barons and chased him out of Athens.

For twelve years, Pisistratus stayed away but he was never without a scheme and he made good use of the time. He toured the Mediterranean collecting a few unclaimed islands and dropping in on any city where the ruler was willing to welcome him. Then, while he was in Macedonia, he got hold of a gold mine. With the profits of a mine he brought an army and in 544 B. C. he was back in Athens and became a tyrant again. When the barons took a good look at his army, most of them decided to leave the polis in a hurry. So did Megacles and none of them came back while Pisistratus lived. He was finally able to rule Athens and even Solon said that, for a tyrant, he did a good job.

For the citizens, it was a fine time. Under Solon’s laws, their little country had grown up. The new shopping district around the market square had become the meeting place of people from every corner of the Mediterranean world. The Athenians, whose grandparents had known only the village gossip of Attica, now talked Egyptian politics, read poetry from Rhodes and told the latest jokes from Syracuse, almost as soon as the Syracusans did but Pisistratus was still not satisfied.

Solon had brought craftsmen and merchants to Athens. Pisistratus wanted builders and poets, anyone who could give the polis beauty and fame. He announced to all the world that once every four years the Panathenaean Festival, the city’s greatest holiday, would include international games and contests. The citizens of every Greek city were invited to enter. Competitors and spectators flocked to Athens, for no Greek could resist a good contest.

The Athenian Games

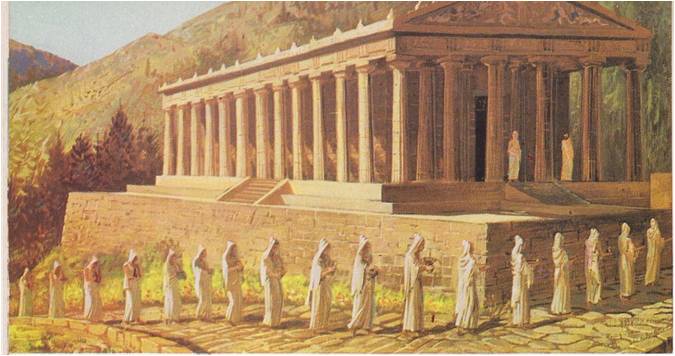

On the first three days of the festival, athletes competed in races and wrestling. There was a contest, too, for the rhapsodes, the minstrels who sang the tales of Homer. On the fourth day, the winners of all the contests joined the great procession of Athenians that wound its way through the city and up the Acropolis to the temple of the goddess. A tall model of a ship on wheels led the parade. On its mast was fastened a magnificent robe which the maidens of the city had woven for Athena. Following the ship rode charioteers and horsemen of the Athenian cavalry. Then came the elders of the city, musicians playing on pipes and lyres and youths leading the animals for sacrifice. Dancers were clicking, castanets wove in and out of the long train of marchers. When the procession reached the temple, the maidens put the splendid robe around the shoulders of the statue of the goddess. The animals were sacrificed at the altar and a hush fell over the people while every man made his prayer to Athena, asking her to remember the city. Then, shouting and singing, the crowd rushed down the hill to the victory feasts and the dancing that would end the festival.

These men who came to compete in the games went home talking about the splendors of Athens and Pisistratus saw to it there was more for them to talk about each time they returned. He had the old wooden temples on the Acropolis rebuilt in fine white stone. Perhaps he hoped that the gods would forgive him for once having made the Athenians kneel before a false Athena. He ordered a new temple for Dionysus, the god of wine and crops. When it was finished, he proclaimed another festival, the Great Dionysia of the City, a celebration that brought about one of the Greeks’ greatest experiments.

The Great Dionysia was held in early spring, when the grapevines had just begun to sprout. For five days, all work stopped in Athens, while the city celebrated the end of winter. The people feasted together and toasted each other with glass after glass of wine. There was singing and dancing around the altar of the new temple.

In the old days, the singers had worn goatskins in order to look like Dionysus’ servants, the satyrs. It was said that Satyrs were half men and half beasts, with pointed ears and tails like horses. Their chants were “goat-songs” – noisy, braying hymns for a god who liked to laugh. Pisistratus had decided to add a contest to this festival, too – a contest for new songs. Instead of goat-songs, the musicians and poets brought songs about other gods and ofcourse, the heroes in Homer. The chorus at the temple changed their goatskins for costumes and went with the stories. Then the chorus leaders began to sing some of the lines as solos, to make the tales clearer and more exciting.

One day the people who had come to watch the song contest suddenly sat up in surprise. Something odd was happening. The leader had just begun his solo but instead of telling a story about a man, he spoke as if he were that man himself. He talked to the chorus as though they were friends he had just run into on the street. It was strange.

The audience had never heard of acting or of plays. Until that afternoon, there had never been a play at all. When it came time to choose the winner of the song contest, the crowd voted to give the prize to Thespis, the man who had written the odd new poem. Pisistratus, delighted, announced a new contest-for plays.

Not everyone agreed that Thespis’ idea was a good one. After that first play, Solon told Thespis that a man pretending to be someone else had to lie to do it. Wasn’t Thespis ashamed to ask a man to tell lies, especially in front of so many people? Thespis answered that there was no harm in it, because the man was playing. Solon struck his staff on the ground angrily. “If we honour that sort of thing in play,” he said, “someday we will find it happening in our business!”

The younger Athenians were willing to take that risk. They hurried to see more plays and built a grandstand beside the clearing in front of the temple where the performances were given – the first theatre.

Meanwhile, Pisistratus was busy with new projects. He had two great dreams. The first was to build a temple for Zeus that would be bigger and more magnificent than any other temple in Greece. The second, was to have his sons and his sons’ sons rule the polis. Perhaps his dreams were too ambitious. Or perhaps, as many people said, Athena had not forgiven him. Both of his projects failed. When he died in 528 B. C., work stopped at his mammoth temple and no Athenian ever tried to finish it. His sons, Hippias and Hipparchus, did rule Athens for awhile. Then Hipparchus was killed in a quarrel and the citizens sided with his murderers. Tyrant or not, they said, he was in the wrong. Hippias overheard their complaints. Fearing for his own life he turned harsh and cruel. The people grew angrier and the barons, who had fled when Pisistratus marched his army into Athens, decided it was time to come home again.

One noble family, the rich and powerful Alcmoenids, had long been plotting the downfall of Pisistratus and his sons. They had wanted Athens to grow weary of tyrants and for the help of soldiers from Sparta. Now Athens was sick of Hippias. It was time for the Spartans to step in and the Alcmoenids knew just how to manage that.

They were famous for sharp trading and getting the most for the money, the Alcmoenids had won the contract to build a great new Temple of Apollo at Delphi. Delphi was the place of the Oracle, who gave advice to the rulers of every polis in Greece. The Oracle’s message came from the gods, but only the priests could understand it, so it was upto them to tell the kings and statesmen what the gods were saying. It was also upto them to worry about the cost of the new building and how it would look. The plans called for good, white stone, but not the best; that would be too expensive, but the Alcmoenids used the hardest, finest stone obtainable and they paid the difference themselves. The priests were delighted and very grateful. The Alcmoenids said they were happy to give Apollo a good home, even though they could not enjoy their own homes at Athens unless the Spartans agreed to fight Hippias. Somehow, after that, whenever the kings of Sparta came to ask the Oracle for advice – whether the question was about starting a war or planting crops – the answer the priests gave them was always: ”Free Athens first!”

The Spartans were not eager to fight, but it was hard to ignore the advice of the gods. They finally agreed to help Alcmoenids and the other noblemen and together they marched on Athens. Hippias and his followers locked themselves inside the walls of the Acropolis. For several days they held of the attackers. Then the Spartans captured Hippias’ children and the tyrant surrendered. He left the city promising never to return.

Athens was free but not peaceful. When the noblemen trooped back to Attica to claim their old estates, the people went to war to stop them. The Coast, the Plain and the Hill began to quarrel again, then joined in the fighting. The bewildered Spartans decided to let Athens save itself and went home. It seemed to them that the Athenians would go on quarrelling until they destroyed each other and their polis. However, they did not know Athens. Once again, there was a man with an idea – Cleisthenes.

Cleisthenes was an Alcmoenid, the leader of noblemen but he was an Athenian first. His plan for a new kind of government for Athens was one which he hoped would put a stop to the feuds and make a good life possible for nobles and commoners alike. When he explained the plan to the Athenians, they agreed to the experiment. It meant making many changes, but almost anything would be better than the constant wars.

First, Cleisthenes divided the citizens into ten new clans. Each had the same vote in the city council and each was made up of equal numbers of people from the Plain, the Coast and the Hill. Old enemies were forced to become allies and the feuding stopped.

There was still the danger that a proud man like Pisistratus might try to become a tyrant but, Cleisthenes had an answer for that, too – a backward sort of election, called “the ostracism”. Once a year all the citizens were called together in the market place and each man was given a clay ballot on which he could write the name of a politician who seemed dangerously eager to be important. The ballots were dropped into huge clay jars, one for each clan. Then officials emptied the jars, threw away the blank ballots and counted the ones with names written on them. To make the election legal, at least 6,000 ballots had to be cast. The man who got the most votes had to leave Athens for ten years. Suddenly there were few men who wanted to be tyrant.

Now Cleisthenes tried his greatest experiment. He said that every official of the polis – the councilmen, judges and planners – would be chosen by the votes of the people. Even the ten generals would be elected, one from each of the new clans. Any citizen could be names.

Democracy Invented

The Athenians, pleased with the system that gave every citizen a place in the government, did their best to make the plan work. The old quarrels began to be forgotten and the experiment was a success. Cleisthenes had invented democracy.

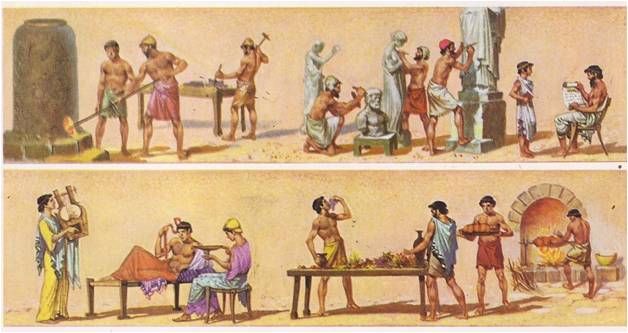

Athens had moved with amazing speed. All the changes, from Draco’s harsh laws to the new democracy, had been made in less than one hundred years. However, there were some things that remained the same and one of them was slavery. Prisoners of war, especially barbarians, were sold as slaves in every Greek city. There were many of them in Athens – a few on the farms, some in the mines and the rest in the city. Most families kept one or two as cooks, cleaners or nursemaids. Craftsmen used them as helpers in their workshops. Often they worked side by side with free men, doing the same jobs. In some cities, slaves were treated with savage cruelty, but in Athens they had a better time of it and there were laws to curb the harshness of bad tempered masters. The Spartans joked about that. They said that when you met an Athenian and his slave in the street, you could not tell the difference between them.

The Athenians, however, knew that there was a difference. A slave was a man who had so little pride that he let himself be captured, giving up his honour to save his skin. It was wrong to treat him cruelly, but he did not deserve to be free.

Not that being free guaranteed anyone the vote. The foreign merchants and craftsmen who came to live in Athens were free men, but many of them stayed for years without being given the rights of citizenship. Though the Athenians were happy to have them do business, they were still suspicious of strangers and in no hurry to let them vote.

No woman could vote, not even if she was a native of Athens. According to an old story, women as well as men had once belonged to the Assembly. Then there was an argument about which one of the gods should be the special guardian of the city. Some citizens wanted Athena, a goddess. Others preferred Poseidon, a god who was a man and a warrior. When it came to a vote in the assembly, all the men voted for the god and all the women voted for the goddess. Since there were more women than men at the meeting, Athena was elected, but the men had their revenge. At the first meeting where they outnumbered the women, they voted them out of the Assembly altogether.

Probably it was just a story. Nevertheless, Athens was a man’s democracy and a man’s city. Women were not expected to go about the streets freely. Their place was at home. Girls spent their time learning to be good wives for citizens, not to be citizens themselves. While they waited for their fathers to come to terms with the men who asked to marry them, they kept busy with ladylike activities: cooking, weaving and especially spinning. The girls who waited too long for marriage were called “spinsters.”

Foreigners sometimes thought that Athenian women must be dull and uneducated. That was because foreigners had almost no chance to meet them. A few foreigners had not heard the Athenian who boasted that his new wife had been brought up to “see as little, hear as little and ask as few questions as possible.” Most citizens wanted wives who were cleverer than that. It was true that a woman had little or no chance to see the world, but she heard about it from her husband. He was her teacher and he expected her to be bright enough to keep up with the things that interested him. He bought her the latest poems and books, discussed politics with her and at festival time he took her with him to the ceremonies and the contests. If an Athenian wife was dull, she probably had a dull husband.

There was little excuse, however, for an Athenian to be dull. He grew up in the most exciting city in Greece and unlike his sisters, he was always in the midst of things. At his birth, his family had celebrated because he was a boy, a future citizen. They spent all that they could afford to train him for his most important job, serving Athens. For six or seven years the little boy was pampered by his nursemaid. She saw to it that his bed was soft and his food the best in the house. She kept a careful eye on him when he rode around the courtyard in his little goat cart.

Then it was time for school. Instead of a nursemaid, the boy was looked after by a pedagogue, a slave who carried his books, guarded him in the streets and made certain that he got to school on time. Classes began early. The student and his pedagogue left the house at dawn, just as the farmers and tradesmen were hurrying to the market place. The school was in the house of the teacher, a poor man, but one who had all the training of the citizen. In the mornings, the students practiced writing on wax tablets with sharp sticks of ivory. The sticks had a blunt end for “erasing” mistakes. When it was time for arithmetic, however, the sticks and tablets were usually put away. The Greek system for writing down numbers was awkward and the boys often used pebbles instead. They called the pebbles calculus and when they counted with them, they “calculated”. The youngest boys had lessons in reading, as well as in writing and arithmetic, but reading was only for beginners. Older students learned by discussions and arguments and by chanting verses from Homer and other great writers.

Music and poetry were most important studies, especially in Athens. Every well-bred Athenian man was expected to be able to play the flute or the lyre, an instrument like a small harp. For music was more than a pleasant way to fill an afternoon or evening. The songs told the stories of the heroes and the gods. They were tales of courage and wisdom and from the boys learned what was expected of citizens.

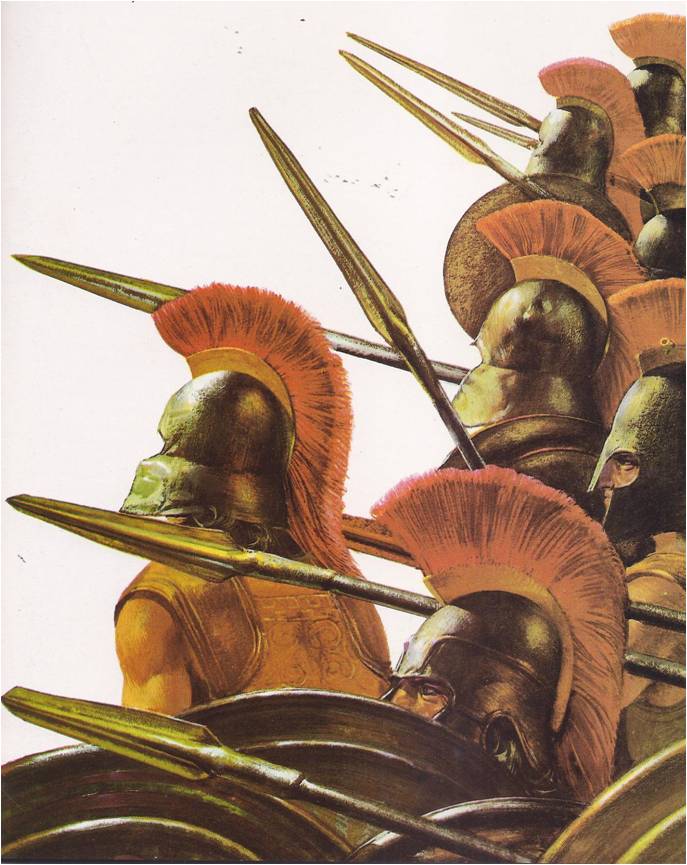

Not all the lessons were taught in the classroom. For several hours each day, school was held in a wrestling academy, a gymnasium which the masters owned or rented. There were games and exercises and training in wrestling or boxing. The boys enviously watched the older athletes, who were getting ready for the international games and they dreamed of the time when they could compete themselves. A healthy mind in a healthy body was the goal of every Athenian. He wanted to excel at everything – to be the best there was. It was the way to win the favour of the gods and it was his duty to Athens.

When they were eighteen, the boys left school. Many of them went on studying, talking and arguing with the wise men who gathered in the market place. They swore the oath of citizenship, but were not yet full citizens. First they had to spend a year training with the army. At the end of that year came the moment for which they had been working all of their lives. On a day that was sacred to Athena and the polis, the young men marched together to the Acropolis. There the people of Athens waited to greet them. As they came to the top of the hill, near the temple of the goddess, the crowds hailed them as citizens, new men of Athens.

On the special day, when the proud young citizens gave themselves to their polis, no one could doubt that Athens was the most fortunate city in Greece.