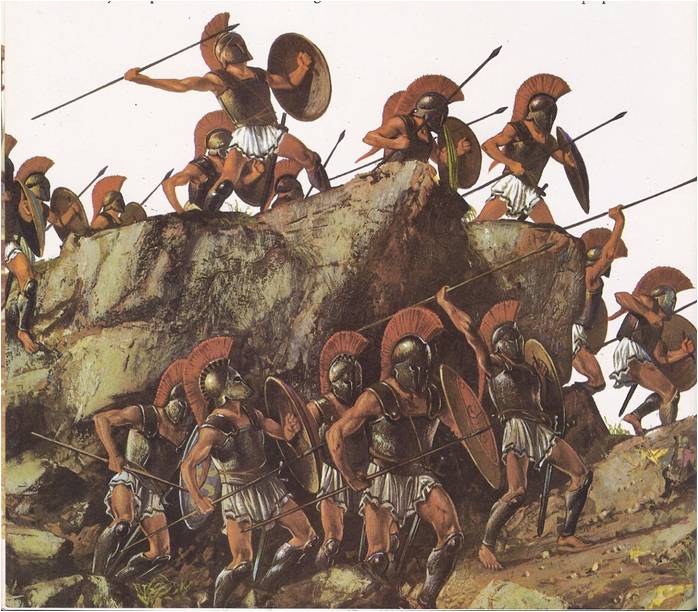

In the first years of Spartan peace, Greece was filled with wandering soldiers. Their little cities needed them no more. The new governments, which Spartans appointed, looked on them as men who might make trouble and were quick to get rid of them. Homeless and with no way to earn a living, the old campaigners roamed from place to place. They became soldiers of fortune, men who fought for any general or city that offered pay and three meals a day. In 401 B. C., ten thousand of them hired themselves out to Cyrus, a prince of Persia, who hoped to steal his brother’s throne.

The Army of Ten Thousand was an odd lot. There were officers and men from a dozen or more Greek states, soldiers who had fought with and against each other during the thirty years of war that had torn Greece apart. Yet, under a foreign commander, they worked well together. They made a strong force which no Asian army could begin to match. Cyrus led them far into Persia and wherever they went they were victorious. Then Cyrus was killed in battle and the Greek officers were tricked and treacherously murdered. The great army suddenly found itself stranded, with neither money nor leaders. The men were not even sure where they were, except that it was hundreds of miles from the coast of Greece.

Election of Xenophon

The Persian king waited for them to lose heart and surrender, as any Asian army did when it had no officers to give it orders. The Army of Ten Thousand was Greek. After a day of confusion, the soldiers called an Assembly and elected a new general, Xenophon, a young Athenian who had been the assistant of one of the dead officers. For four months he led them through a wilderness of mountains, while Persian cavalrymen hurried them and icy winds cut through their flimsy summer uniforms. Their food was whatever they could take from the strongholds of mountain tribes along the way. Gradually, they abandoned their baggage and the prizes they had won in battle; it took all their strength simply to go on.

One day, as the weary army dragged itself to the top of another steep hill, the men in the lead gave a great shout. Xenophon, thinking it was an ambush, rushed to the front of the column, but he found no fighting and his soldiers standing with tears running down their faces. They pointed ahead, beyond the slope of the mountains and the fields below. “The sea”, they shouted, “the sea!”

To a Greek, the sea meant home. The long march was over.

When his men had returned safely to Greece, Xenophon gave up his command, but he did not go home. Athens had sent him away and the citizens did not invite him to return. The Spartans, however, offered him an estate in the Peloponnesus, a fine piece of land with a wide meadow, streams and thickly wooded hills. Xenophon loved hunting and fishing and he accepted the Spartan offer. He built a house especially designed to catch the sunlight all the year, planted an orchard with every sort of fruit tree known in Greece and settles down, content. In the mornings, while the mists still drifted across the meadow, he and his hounds chased wild boar and deer. After lunch, he worked at a book he was writing.

Like Thucydides, Xenophon was an exile, far from his home. Like him, he had lived through the dreadful time when Athens tried to win the world and lost everything. His book was not a tragic tale of men and cities ruined by war. Thucydides had told only one part of the story of the Greeks. Xenophon told another. He wrote about the bravery of the Ten Thousand, about good fellows who dined together and talked until dawn and about the best of times in a splendid world of Greeks. That was the world that he and his soldiers had feared they might never see again. It was a pleasant book about a pleasant life, a little stuffy sometimes and old-fashioned, like Xenophon himself.

Other men told parts of the story. They remembered the days before the war and the months when the fighting had been far from the city. Then Pericles’ Golden Age continued, they said. Life was good and Greece was still a land of poets, athletes and wise men. Later, when people who were not Greeks read the books, they were sometimes confused. It did not seem possible that all the writers were talking about the same place. The readers had forgotten that one Greek could be many things – a soldier one day, a merchant the next and a statesman the day after that.

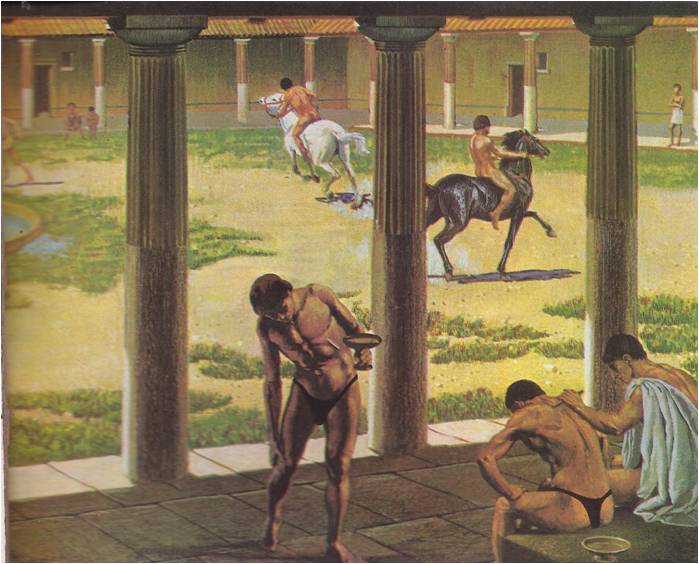

Xenophon, the young adventurer, became a country squire. He puttered about his orchard and entertained the friends who came for a week or two of quiet. Once every four years, however, his house overflowed with guests. Athenian friends and old companions from the long march turned up from every part of Greece to attend the games at Olympia, just two and a half miles down the road. They stabled their horses in the meadow, set up camp in the orchard and each morning they rode out to watch the contests.

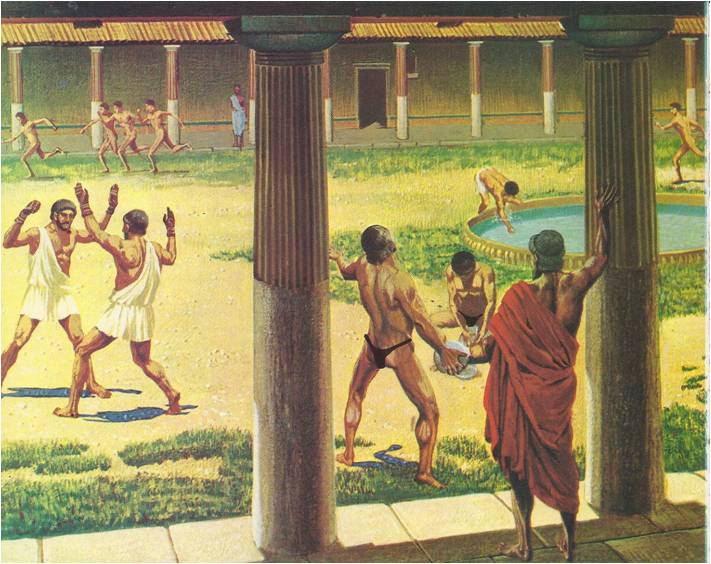

At Olympia a city of tents had sprung up around the temples and the stadium. Every polis put up a camp for its own athletes and trainers. There were dining pavilions, gymnasiums and a long row of peddlers’ booths, like the midway at a fair. There were beggars, fortunetellers and souvenir-sellers and even scholars who showed off their skills to the thousands who had come to see the games.

No quarrel between men or cities was allowed to interfere with the great festival. A month-long truce protected the athletes who had to travel through enemy territory on their way to Olympia. No city dared to break the truce, for the Olympic Games were sacred.

The First Olympic Games

At Olympia, it was said, Zeus had fought with his father Cronus for the right to rule the universe. To celebrate his victory, he called for the gods to match their strength and skill on the same field. In those first Olympic Games, Apollo outraced Hermes, the wing footed messenger of the gods. He boxed with Ares, the god of war and defeated him.

Later, when the greatest athletes of Greece came to Olympia with dreams of winning victories like Apollo’s, Zeus was still the guardian and final judge of the contests. His statue, a huge figure of gold and ivory, stood above the fields. On the first day of the festival the athletes brought their sacrifices to the altar. They prayed for victory and swore to compete fairly.

Then came the four days of contests. First there were junior events, for lads eighteen and younger – sprints, track events and wrestling. The men’s contests began on the third day of the festival. There were footraces including a 200-yard dash and an endurance run of two or three miles. Then the heavyweights took over the field for Pancration, a rugged hand to hand fight of two men, which combined boxing and wrestling. In practice the athletes wore caps to protect their heads and ears, but at Olympia they fought without them. They hammered each other with fists bound with leather strips, which saved their knuckles but did nothing to soften their blows. They tried to throw each other with a “flying mare” or a “wrestlers’ heave”. Anything was allowed except biting and eye-gouging and the fight continued until one of the contenders gave the sign of defeat. Sometimes the battle was ended by death.

The fourth day brought the Pentathlon, a less savage contest for all-around athletes. Each man had to compete in the five events: sprinting, regular wrestling, the discus throw, the javelin toss and the long jump. The discus was a round, plate like weight of stone or metal, thrown for distance. The spear like javelin was thrown for accuracy at a target. In the long jump, an odd sort of broad jump, the athletes were not allowed a running start; instead, they held heavy weights which they tossed behind them when they leaped, to give themselves an extra push forward.

While these events were going on in the stadium, there were others in Hippodrome, the horse arena. There, bareback riders raced their mounts and charioteers, some of them kings or princes, showed off the fastest teams in Greece. The chariot racing was wild. The drivers urged on their horses, tilted and crashed against other chariots, risking anything to come in first.

Winning was the aim of every man at the Games. In other times and places, athletes found a kind of reward in playing a game well, whether they won or lost. For a Greek, victory was the only thing that mattered. He spent years training himself, then tried his strength in the games in his own city. If he won these home-town meets, he went on to Olympia and the three other international contests: the Isthmian Games at Corinth, the Pythian Games at Delphi and the Nemean Games which, like the Olympics, were held in the Peloponnesus. At each of them he tried to prove that he was the best man and to show the gods that he had the strongest will to win.

The Laurels

The winners prize at Olympia, awarded at the ceremony on the last day of the festival, were simple wreaths of olive leaves but it meant fame and honour which only the greatest heroes could expect. As the victor rode home, he was hailed in town after town. The important men of his own polis came to meet him on the road and formed a procession to conduct him into the city. Sometimes a section of the city wall was torn down, making a new gateway for the victor. “What need have we for the walls,” the people said, “with such men to defend us?” They put him into a four-horse chariot and led him to the shrine of the city’s guardian god. There he placed his wreath on the altar as an offering. A feast was given in his honour and when the banqueting was over and the toasts drunk, there was singing by the chorus that performed at all the city’s festivals. This night they chanted a new ode, a song which told of the athlete’s victory.

No one thought it odd that a serious poem should be written about a foot race or a wrestling match. Pindar, the greatest writer of odes, wrote his poems in praise of athletes. A victor, he thought had something of god in him and the new heroes of the games were a sign that Greece still had men like Homer’s heroes. A poem was a proper way to tell about such godlike men, or about anything so important that it ought to be remembered.

Whenever a Greek read Homer’s poems, the Achaeans seemed to live again because of Homer and the old warriors could never be forgotten, nor could their gods. Another poet, Hesiod, had followed Homer’s example and had written down more of the tales of Zeus and the adventures on Mount Olympus. He called his book Theogony, “The Doings of the Gods.” Hesiod, was a farmer in the back country. “A poor place,” he called it, “bad in winter, hard in summer, never good.” Planting and the harvest were battles he fought every year. So he wrote about them, too, in Works and Days, a farmers’ almanac in poetry. He gave advice on when to plow, how to cultivate and how to prepare for winter. He had suggestions for relaxing in spite of the heat of summer and made a few cautious remarks about the dangers of sailing as a landlubber saw it.

That was about 700 B. C. A hundred years later, all of Greece had developed an ear for poetry and it seemed that nearly everyone was writing it. Any intelligent man, in fact, was expected to be able to do it, just as he could play the harp or flute. Politics and laws, love and history were all set out in verses. Ofcourse, few men were upto writing epic poetry, the long story-poems like those of Homer and Hesiod. Odes like Pindar’s were for grand occasions and meant to be sung by a chorus. Other people, especially those who wanted to tell of their love or sadness or both, wrote lyrics. There were songs sung to the accompaniment of the lyre, the little Greek harp.

The most famous of lyric poets was a woman, Sappho, who lived on the island of Lesbos about 590 B. C. It was said that she kept a school for girls, but the Greeks remembered her for her love songs. Years later, historians and other sober-minded men wrote their thoughts in prose; fewer people wrote poetry. Then, men and girls in love found in Sappho’s lyrics the words which expressed their feelings. More than any other poet, she seemed to know what she longed to say themselves. Only she could teach them how to beg Aphrodite not to break their hearts.

Greek Tragedy

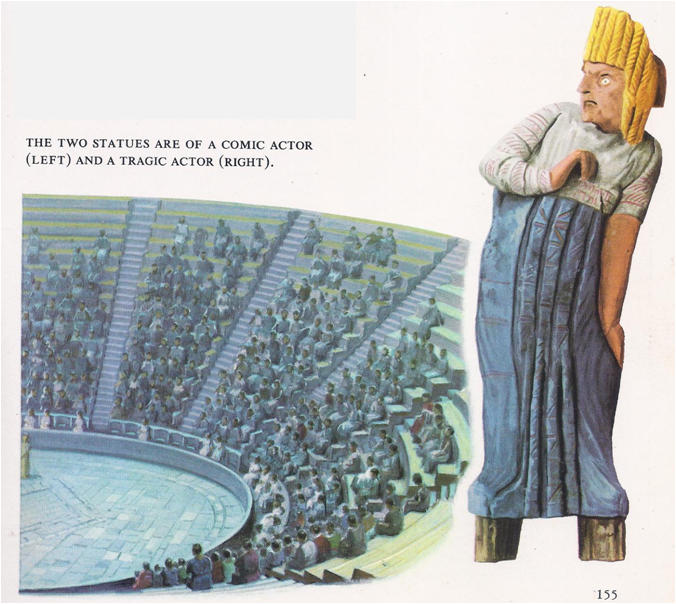

In Athens, where poetry turned into plays, poets could be heroes, as honoured as the Olympic athletes. In Pericles’ time, the contest for playwrights, begun by Pisistratus, became the most exciting event of the year. Even the wars were not allowed to interfere. At the base of the Acropolis, a great new theatre was built, big enough for ten or twelve thousand people. On contest days, some spectators arrived before dawn to make certain that they would have seats. By an hour after the sunrise, the crowd was pouring into the rows of stone benches, carrying cushions and sandwiches. From their seats they looked down into their clearing where the old satyr-dances had once been performed. Now it was brushed clean and circled by a ring of white stone. Behind it was the building where the actors changed into their costumes and beyond, the hills and fields stretched away to the sea.

When the theatre was filled, the priests and city officials took their places in the marble seats in the front row. A hush fell over the great crowd and the signal was given for the play to begin. The chorus came on the stage and then the first of the actors. A large wig and boots with soles several inches thick made him tall. He wore a huge mask, painted to represent his character, so that even the people in the topmost rows could see who he was. When he spoke, a device like a megaphone, built into the mask, let everyone hear clearly.

The play was very different from the acted-out songs which Thespis wrote. There were four actors now as well as he chorus. Changes of costume and masks allowed them to play many parts. Painted scenery was hung on the actor’s dressing house and from its roof was suspended a “god-machine,” the mechanism which “flew” the gods and their messengers above the heads of the other actors.

Such things helped to bring to life the old stories which the plays told. On the clearing below the grandstand, Agamemnon, Hector, Achilles and Helen of Troy lived once more. Agamemnon came home to his castle at Mycenae and at the end of his play, he was killed by his treacherous wife. The great doors of the dressing house were flung open to show him lying dead. The chorus, always on stage, watching and commenting, mourned the death of the king and told what it meant to those who still lived in the world of men.

Each morning of the contest, one playwright presented a trilogy – three plays which told three parts of one long story. Since the stories were old, the audience always knew what was going to happen – Agamemnon would die, Troy would fall, or the Trojan women would weep for the loss of their city. The crowd came to see how a new playwright would use the old plot and what new meaning he would find in it.

In the death of the kings, there were lessons which touched everyone, but three playwrights could find three different lessons in the same story. Aeschylus, an early playwright, always looked for justice. Some years later, however, Sophocles set out to show his audiences that they must accept life as it was, just or not. Then the wars brought misery to Athens, and another playwright, Euripides, could only write off suffering that seemed cruelly unjust. Each of the three writers won prizes at Athens in his time. Each of them added something of his own to the tragedies, the majestic plays of Greece. Together they won for a tragedy a place in the world for all time.

There was laughter in the theatre, too. The contest of plays was still held to honour Dionysus and no one forgot that he was a god who enjoyed laughing. Tragedy was the morning’s business. In the afternoon, the comic playwrights took over. The actors who bounced onto the stage after lunch were much more likely to pretend to be Athenian heroes. No one was safe from their jokes. They called Pericles “Onion Head” and boastful Cleon “the son of thunder, a robber with the voice of a waterfall.” Aristophanes, the greatest of the comic writers, made fun of politicians, sculptors, poets, professors and ordinary Athenians sitting in the audience. No over-eager speaker at the Assembly or pompous merchant in the market place escaped his sharp eye. Sooner or later, they turned up in a play. Only in Athens, where men were free to speak their minds, could such a thing have happened. Aristophanes used this right to point out the foolishness and pride which threatened the good of the city.

Mocking the Gods

The gods, too, were victims of Aristophanes’ humour. In one of his plays, he made the god of war a cook, stirring up a salad – Corinth was the grated cheese and Athens the honey for the dressing. Once he said the Athenian character up in the “god-machine” to ask the gods for peace. When the man knocked on the door of Zeus’ palace, no one was home but Hermes, the messenger. His message was that the gods, tired of humans and their wars, had gone on vacation.

Some people did not laugh at this comedy, because they wondered seriously if the gods were still on Olympus. It had become hard to believe in myths which told of gods who fought each other and perched in clouds. Many Greeks began to doubt that the gods the old poets talked about really existed at all. They still respected the things that the gods stood for – Apollo’s discipline and Athena’s wisdom. They were sure, too, that some power strong and good, ruled the world, but it did not matter whether they called it Zeus or Fate or simply God. As for the old myths, they were good stories that helped to explain important ideas. A good example was the tale of the battle of the Lapiths, whose wives were stolen by centaurs who were half men and half horses. The storytellers said that Apollo helped the Lapiths win the battle and get their wives back. Whether the story was true or not, it taught that the lawlessness of beasts had given way to the order established by men. People were free to believe the myths or not, just as they pleased. If a man said that Apollo had nothing to do with the eclipse of the sun and tried to find out what caused it, no one stopped him.

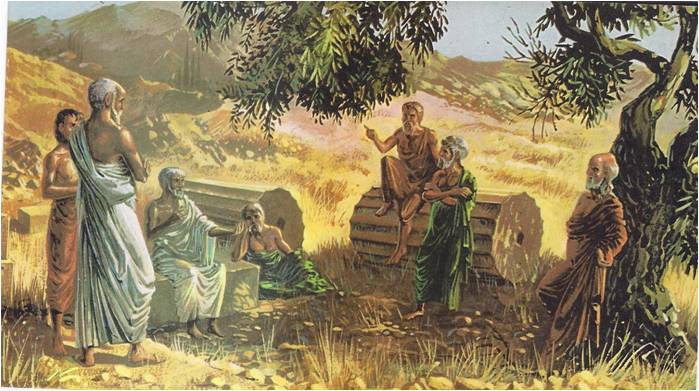

In Athens in the time of Pericles, men strolled along the paths in the groves beside the playing field and talked. Some of them discussed business, some argued politics – and some had minds that were filled with questions. They had been to school and they had travelled to other lands but when they tried to learn the truth about the world around them, there were many facts and few explanations. In the groups that gathered around the benches, they found other men who were troubled by the same difficult questions. “What is the universe?” they asked. “Why does man exist?” Day after day they argued about the possible answers. If a stranger stopped to listen and asked one of them what they were talking about, he was told: “Philosophy.” In Greek, the word meant “the love of wisdom.”

Philosophy did not begin in Athens, however, but in Miletus in Asia Minor. There, in the sixth century B. C., a group of men became fascinated with the question: “What is the universe made of?” One philosopher, Thales, suggested that everything was made of water. Another, Anaximenes, noticed that clouds were made of air and eventually became water, so he said that everything was made of air. A third man, Anaximander, disagreed with them both. He said that whatever it was that came first was something invisible, called the “Unlimited,” and everything visible came from it.

None of the answers seemed altogether right, perhaps because the men were assuming that the universe was made of just one thing. Nevertheless, they had the courage to ask the question and they had discovered a way to find the answer – by looking at the world and thinking logically about what was there.

In 585 B. C., Thales believed he knew what caused the eclipse of the sun. He predicted when the next eclipse would happen and he was right. Then Anaximander built a model of the heavens in order to study the way the planets moved. For the first time, the storytellers, with their tales of the gods, had to face up to scientists.

Meanwhile, a group of men in the Greek cities in Italy had come up with a different kind of answer to the old riddle of the universe. Mathematics, they said, would explain the world. Their leader, Pythagoras, discovered a basic law of geometry, the Pythagorean Theorem: In any right triangle, the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. He also noticed that the notes of a musical scale had a mathematical order. When he saw that such different things such as music and geometry could be explained by mathematics, he decided that “things are really numbers.” Other philosophers answered that mathematics might show how things went together in order, but it did not explain what things really were and the debate went on.

The Problem of Change

In the early fifth century, people began to argue about a problem of change. They wanted to know how something that looked permanent could turn into something else. What really happened, for instance, when a log turned into ashes? Heraclitus, a philosopher from Ephesus, argued firmly that everything was always changing. The nature of the universe was change. “You cannot step into the same river twice,” he said, “for new waters are flowing on.” Parmenides, a philosopher from Elea, said just as firmly that Heraclitus was insane; there was no such thing as change. Everything was always the same but some things merely looked as if they were changing.

To many of the Greeks it seemed that Heraclitus and Parmenides were both wrong. It was common sense that some things change and some do not. Anyone who said it was all one way or the other was simply unreasonable. On the other hand, they had to admit that the arguments which the two men used to back up their ideas seemed reasonable. It was a puzzle and people began to get discouraged about philosophy. As they wandered from one group of talkers to the next, they heard no reasonable answers. The philosophers could not even agree with each other.

In Pericles’ Athens, where a boy learned to argue when he learned to talk, a new group of scholars turned up. They called themselves Sophists, which meant “wise men” and they proclaimed that philosophy was a foolish waste of time. One of them said: “There is no answer to our questions about the world; if there were such an answer, no one would be able to find it; and if someone did find it, he wouldn’t be able to explain it to anyone else.”

The Sophists set themselves up to teach anything that could be explained. Being practical men, they did for pay. A few old-fashioned philosophers labelled them “wisdom-peddlers.” However, in democratic Athens, where any man could get ahead if he was clever, the Sophists did very well indeed. One of them promised that for a small fee he would teach anyone “the whole duties of man.” Another said that he was an expert at arithmetic, geometry, mathematics, grammar and literature; and was ready to answer any question.

The most important thing the Sophists taught was rhetoric, the art of speaking in a way that persuades people. That was the key to success in the Assembly and the law courts, the places where a young politician could make a name for himself. The Sophists’ pupils learned to speak elegant phrases, to argue a point cleverly and to move the sympathies of a jury. One of the teachers promised that a man who paid his fee and took his course would be able to win any lawsuit; but he changed his guarantee after one of his students refused to pay and suggested that the teacher sue him for the money in the law courts. The young men who learned from the Sophists embarrassed their elders with clever arguments. So, ofcourse, the elder citizens said that the Sophists were leading the youths astray and ruining Athens.

Socrates

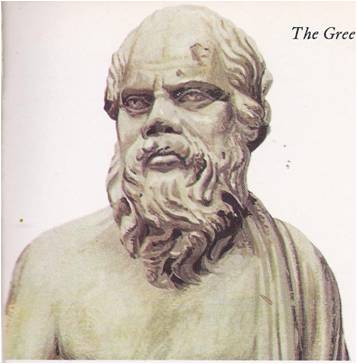

About this time, a stone carver named Socrates began to spend his time talking in the market place. He said that his purpose in life was to seek the truth. Soon he had quite a circle of followers and some of them were young men from the best families in the city. Socrates was bald and had a potbelly, but when he spoke, people forgot what he looked like. His words and his ideas seemed to make everything else unimportant. Athens had never before known such a teacher and many people wanted the honour of studying with him; but Socrates chose his students carefully. He quickly sent away anyone who was seeking honour rather than learning.

Socrates was a poor man and his wife was forever nagging him for spending his days talking instead of earning money. Even so, he charged his students no fees. He disliked the Sophists, who taught for pay and felt that they were giving philosophy a bad reputation. He also taught that the first philosophers had asked the wrong questions, because they began with the universe instead of themselves. “What is man?” asked Socrates. “How can a man lead a good life?”

The good life did not mean riches or fame, but wisdom. A man had to begin by knowing himself. The first step, Socrates said, was admitting that he really knew nothing. He was greatly puzzled when he heard the Oracle at Delphi had named him as the wisest man in the world and he set out to find someone wiser in order to prove that the Oracle had made a mistake. In the end, he decided that perhaps she was correct, if she meant that the wisest man in the world was the one who knew just how ignorant he was.

Socrates became a familiar figure in the market place. Year in, year out, he was there and always with a cluster of eager students. Even the proud Alcibiades was humble before him. His fame grew, but not his riches. Somehow he managed to scrape together the money for his household bills and his students saw to it that he was at least well fed. The discussions that started in the marketplace continued through the evening at dinner parties where Socrates and his friends talked far into the night. They spoke of the meaning of justice, of friendship, of love and of courage. There was also much joking, often at Socrates’ expense. The tales about his sharp-tongued wife were told time and again, for she had never changed her mind about the time he “wasted” talking.

When Athens went to war, Socrates went, too and he proved to be as good a soldier as he was a philosopher. The troops remembered him for the time he stood all night in one spot, thinking through an idea.

Death of Socrates

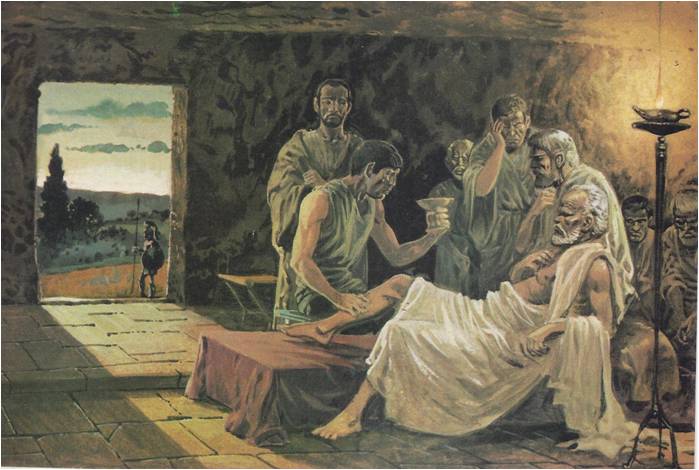

After the war, Athens was nervous and afraid. The citizens were suspicious of anything out of the ordinary which might upset things and make them worse than they already are. Socrates was the most ordinary man in the city; he had earned the hatred of a number of noisy, important men by showing up their ignorance. They began to say that his free way of talking was dangerous, that he had an evil influence on his students. They reminded people that he taught Alcibiades, who had led Athens to ruins and Xenophon, who was fighting for the Persians. Eventually Socrates was put on trial before the jury of 501 Athenians. The charge was “failing to believe in the gods of the city and corrupting the youth of Athens.” He was convicted by sixty votes and the sentence was death. According to custom, he was given a month longer to live. Then he was to kill himself by drinking a poisonous tea brewed from a little plant called the hemlock.

Socrates went on chatting with his friends as eagerly as before. He held firmly to his belief that man had the power to discover the truth. When the time came for him to drink the poison, he still looked for the good. “I am persuaded that it is better for me to die now and to be released from trouble,” he said.

For Athens, the death of Socrates in 399 B. C. was the last and greatest defeat of the war. The people had voted against freedom itself and condemned wisdom in the name of the goddess who was supposed to guard it.

Socrates had never written down any of his philosophy; but one of his young students, Plato, was determined that his words would not be forgotten. He began to write a series of dialogues, like the conversations which Socrates had had with his friends. First he set down a record of the trial and his teacher’s final days. Then he wrote about Socrates’ early life and made certain that no one could mistake him for a Sophist or an enemy of Athens. In the dialogues he described the dinner parties and the walks through the city; the friends who were always there and the talk that changed the Greeks’ way of thinking.

As Plato wrote more dialogues, however, the philosophy gradually became his own and not Socrates’. For men who looked for the truth, he had a story. It began with prisoners chained in a cave. Behind them a bright fire flickered. Between the prisoners and the light of the fire, figures came and went, carrying odd cut-outs of trees and animals and hills. The prisoners, bound so that they faced the wall of their prison, could only see the moving shadows. For them, the shadows were truth. If one of the prisoners was set free, he could turn and see the fire. At first it would be too bright for him to look at it but when his eyes grew used to the glow, he would walk beyond it to the mouth of his cave. There he would find the sunlight and again the brightness would blind him, but eventually he would see the real trees and animals and hills – the truth. When he returned to the cave and tried to tell the others what he had seen, they would not believe him. They would laugh or grow angry, as some Athenians did with Socrates. Even so, Plato said, he would try to explain it to them, to try to set them free.

Plato told the story in the Republic, the most famous of his dialogues. There, too, he wrote about his plans for an ideal state. It would be ruled by philosophers, he said, men who were free from the old territories of power and greed. Its foundations would be the four Greek virtues: courage, temperance, wisdom and justice.

Plato’s Academy

In the grove where he and Socrates had walked together, Plato started the Academy, the first university in the western world. His students came from every part of Greece. One of them was Aristotle, a bright seventeen-year-old who turned up in 367 B. C. Plato was sixty then. He and his young pupil made an odd pair when they strolled chatting along the paths. Often they seemed to think as differently as they looked. Plato wanted to see the universe all at once. Aristotle wanted to know the secrets of each of its parts; but they shared a love of truth, though they looked for it in different ways. Later they shared a place in the memory of the world as two of the greatest Greek philosophers.

When Plato died in 347 B. C., Aristotle left Athens. Some years later in 335, he came back to found his own school, the Lyceum. His students soon decided that he lived up to the claims of the sophist who had boasted that he knew everything. They heard him lecture on one subject after another and in each he was a master. He gave them their first ideas about biology. He gave them rules for logic, laws for poetry and others for rhetoric. His first lesson in every subject could be written in one word: “Look.” He sent his students peering and poking at plants and spiders, at the stars, the sea and everything around them.

Many of the young philosophers at the Lyceum acted more and more like scientists. In Plato’s time, science had been pushed aside. Studying the world of shadows, which was all a scientist could look at, did not seem important. A few scientists had kept at it, of course. Hippocrates had changed the whole idea of medicine by studying symptoms instead of magic. Now Aristotle spoke in favour of science. His lecture notes for astronomy, physics and biology had enough in them to keep the scientists busy for 1,600 years. They brought him such fame that he was simply called “The Philosopher.”

In every subject, the Greeks seemed to lead the world. Never before had people been so certain that they would find what they looked for – the perfect shape for a temple, a first prize at the Olympics, a good life, or the truth about the universe. Like the little city-states, each man went his own way. For the cities, that brought squabbles, wars and disaster; but for men, it meant freedom and the courage to try out their new ideas. “We must follow where the arguments lead us,” Socrates had said and in two thousand years the world was still following the paths which the Greeks had discovered.