Although the Exodus of the “children of Israel” from Egypt is rightly to be regarded as one of the greatest milestones in human history, in the context of the age in which they lived it must have seemed a very small, even trivial event. The Egyptians themselves would have regarded it as just one more tiresome episode in a constantly recurring situation. For centuries the bedouin tribesmen of Sinai and south Palestine had been permitted from time to time to bring their flocks to the fringes of the fertile Delta in search of pasture; whenever there was famine on the steppelands, the cry would go around, “There is corn in Egypt!” From time to time, when the nomads, grown numerous, sought to move farther in and settle, the army of Pharaoh would be sent to expel them from the borders once more. They had outstayed their welcome.

Archaeology has not yet provided any material remains that could throw light on the story of the sojourn in Egypt and of the Exodus. Circumstantial details contained in the narrative, however, and our knowledge of the wider history of the age, suggest that Joseph and Moses fit best into the context of the Nineteenth Dynasty, when the residence city of the Pharaohs was not Thebes or Memphis, but Pi-Ramesses in the eastern Delta, probably that same city called “Raamses” which the Hebrews are said to have helped to build. The Pharaoh of the Exodus in that case is likely to have been Ramses II, who founded this new city and embellished it with fine buildings and gardens.

The Reign of Ramses II

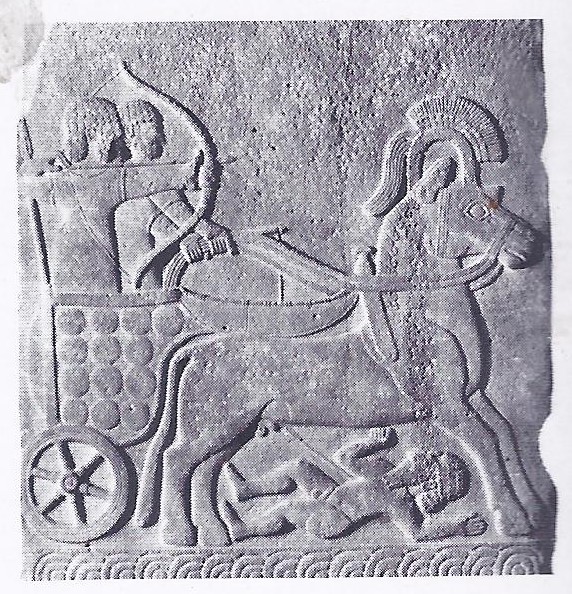

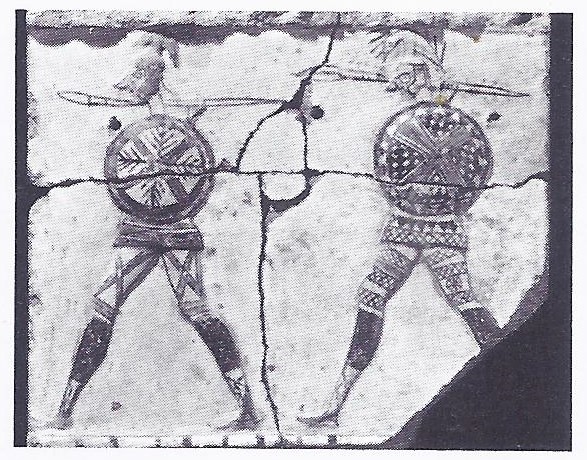

Ramses II is one of the most impressive figures in the whole history of the ancient Near East. His long reign of sixty-seven years (he lived to the age of ninety) was a time of great prosperity for Egypt. The resources of the country were developed, trade and industry flourished. A vast program of temple building was carried through. In every city in Egypt and Nubia his monuments proliferated. Quarries and mines were opened and wells dug in desert places to ease the lot of the miners. In front of the astonishing temple of Abu Simbel, carved in the living rock, there are four colossal figures representing, not the great gods of Egypt, but the king himself seated in fourfold majesty, his face towards the rising sun. In the lofty hall of this temple and on the walls of others throughout the land, Ramses caused to be depicted, in flamboyant detail and in huge size, scenes from the great battle which he fought against the combined forces of the Hittite Empire and their allies in the year 1300 B.C., the fourth year of his reign.

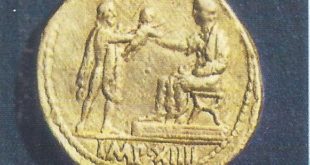

The battle took place near the city of Kadesh in Syria. Almost single-handed, if we are to believe his account, he had charged the enemy in his chariot and driven them sprawling backwards into the river Orontes. (It was a theme of which the court poets and sculptors did not tire. In spite of his claim to have won a great victory, however, this trial of strength seems to have ended in stalemate. His greater achievement was the treaty of “brotherhood” which, after years of negotiation, he subsequently made with the Hittite king, Hattushil and which proved to be lasting. By a fortunate chance of survival, the text of this treaty survives in both the Hittite and the Egyptian versions, the one carved in hieroglyphics on a stone stele in the temple of Karnak, the other in cuneiform on tablets found in the Hittite capital, Hattusas, the modern Boghazkoi.

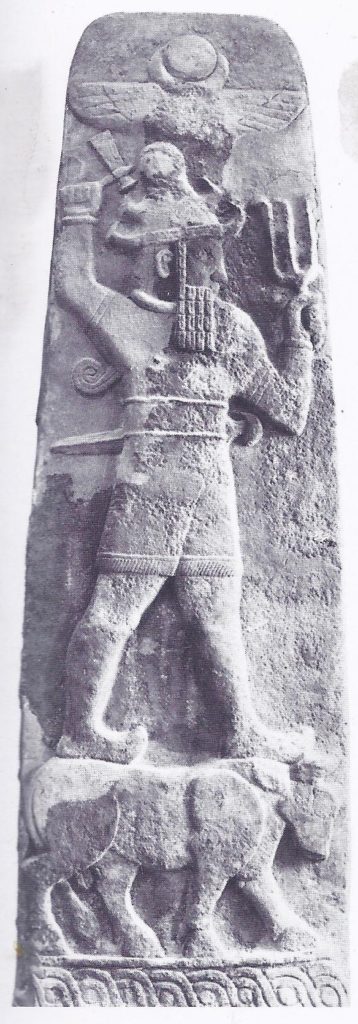

The treaty was cemented by the marriage of Ramses to the daughter of the Hittite king. She was sent to Egypt with an escort befitting so important a traveler and her way was made easy, we are told, by the storm god who caused the winter snows of Lebanon to melt and the sun to shine as she passed by. The entente cordiale was not thereafter broken by either side. The Hittite Empire became increasingly preoccupied with struggles to maintain their empire in Anatolia and were content to maintain their position in North Syria, while Egypt was left in possession of the Phoenician coast, all of Palestine and probably also of the land beyond the Jordan. If the armies of Joshua and Gideon were at this time moving into “the land of milk and honey,” they must have found themselves in territory still at least nominally Egyptian and in part garrisoned by Egyptian troops.

Canaanite Strongholds

Unfortunately, archaeological evidence for the destruction of the Bronze Age cities of Palestine mentioned in the Biblical narrative is curiously inconclusive. The dramatic story of the fall of Jericho cannot nowadays be substantiated by the remains of fallen walls. On the sites of Lachish and Hazor — both mighty Canaanite strongholds — the evidence of pottery suggests a date late in the thirteenth century for the conquest and Tell Beit Mersim, which is thought to have been the ancient city of Kiriath-Sepher, fell at about the same time. In each case, no break in civilization is apparent between the levels below the layer of rubble and ash that marks destruction and the levels of rebuilding above. It may rather be that one of the campaigns of Merneptah, the son and successor of Ramses II, was responsible for the calamity; in one of his inscriptions he claims to have crushed rebellion: “Canaan is plundered, Askalon is taken and Gezer seized; the people of Israel are desolate and have no seed. Palestine is widowed for Egypt.”

This mention of Israel is unique in Egyptian writings and suggests that by 1230 B.C., the approximate date of the events described in the long text of the stele, some Israelites were already established in the Promised Land.

Threats to the Hittite Empire

The Hittite empire, meanwhile, was already running into difficulties. Assyrian armies were marching west and threatening Syria from across the Euphrates and the turbulent Gasgas, barbarians from the northeastern mountains, constantly menaced the homeland. Hattushil had kept both at bay by military action and admit diplomacy, but after his death in about 1250 B.C. his son, Tudkhaliya IV, met with opposition from a different quarter: from a hitherto friendly neighbour on the Aegean coast. This was the king of Ahhiyawa, who now began unwelcome interference in the affairs of the western dependencies of the Hittite empire.

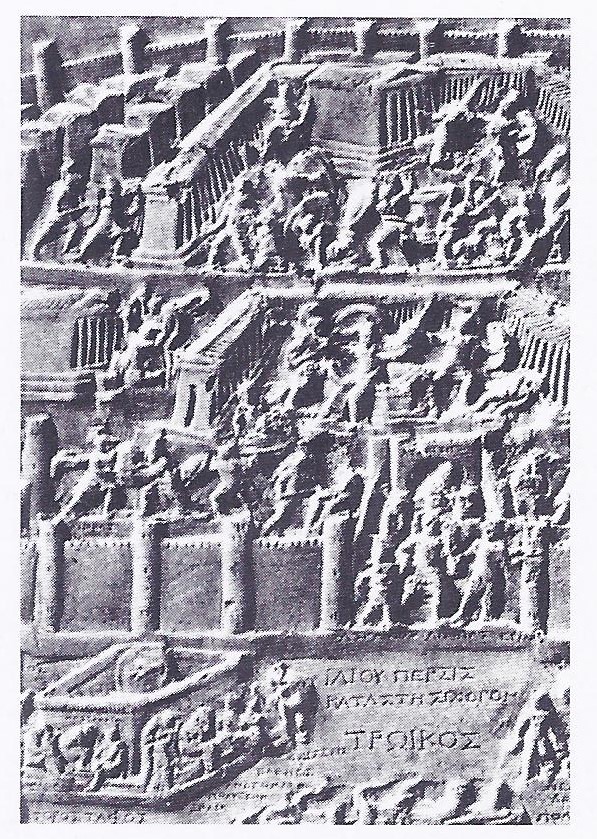

The land of Ahhiyawa is still not certainly located. Many scholars, however, believe that the Ahhiyawans were the people who play the chief role in the Homeric epics — the Achaiwoi or Achaeans, warlike Greeks from the mainland and the islands who mustered their ships and under their leader, Agamemnon, sailed to attack Troy. The story of the ten year siege of Troy by the Achaeans is the story of the Iliad. Now, judging by the geographical distribution of the confederate cities and the description of the warriors’ dress and accouterments as transmitted in the tradition that survived till Homer’s day, it is clear that these Achaeans were the same people whom archaeologists have named the Mycenaeans, the Greek-speaking warrior race who occupied Crete and the islands of the Dodecanese after the fall of Knossos. Their seafaring merchants established colonies or trading posts over the whole of the eastern Mediterranean and even penetrated west of Sicily to the coasts of Italy, France and Spain. Mycenaean pottery is found in Cyprus, in the cities of the Levant, in Egypt and some have been found, too, on the west coast of Turkey.

The kings of Ahhiyawa who sheltered fugitives from the Hittite court may well have been Achaean Greeks whose kingdom — somewhere on the fringe of the Hittite empire, perhaps in Caria or on the island of Rhodes — now constituted a threat to peace. In a treaty between Tudkhaliya IV and one of his vassals, the king of Amurru, the Hittite king refers to “the kings who are of equal rank with me: the king of Egypt, the king of Babylon, the king of Assyria and the king of Ahhiyawa,” but the words “and the king of Ahhiyawa” were subsequently deliberately erased from the tablet. Fortunately the signs are still legible and we are left wondering what crisis in Hittite affairs had led to the hasty removal of the offending phrase, perhaps by some scribe who had been lacking in discretion.

End of the Hittite Empire

In the reign of Tudkhaliya’s successor, Arnuwanda III, the situation became more critical: a rebel made common cause with Ahhiyawa and occupied wide territories in the southwest of Asia Minor. In the east, a hostile attack by one Mita, or Midas, suggests that the Phrygians, who were destined later to occupy the Hittite homeland, were already in league with other mountain peoples against their former overlords. In these texts we can dimly perceive the first stirrings of great movements of populations, the origin and direction of which we do not yet understand, but which were to topple the great empire of the Hittites and change the map of the Near East.

The end came in the reign of Arnuwanda’s brother, Shuppiluliuma II, ill-fated bearer of a great name. At his accession, a little before 1200 B.C., he must already have found himself at the head of an army fighting for its life. The records from Boghazkoi tell of naval battles. Tablets from Ugarit, still a Hittite dependency, reflect a state of emergency in North Syria at the approach of an enemy who is not named. These tablets, some of them letters, were found in the oven in which they had been packed for baking; there had been no time to take them from the kiln when the city met its final destruction. Ugarit was sacked and burned, never to be rebuilt. Other cities of Anatolia and Syria met the same fate. Hattusas itself suffered a great conflagration and wherever excavation has been undertaken on Hittite sites, the destruction is only too apparent. So complete was the disaster that no written record of it has survived, save in the annals of the one kingdom that was able to withstand the invaders. That kingdom was Egypt.