It was summer in 1939, vacation time for lots of people. No one knows how many Americans heard the voice of the British statesman Winston Churchill coming over the air on August 8, less than a month before World War 2 began. His words were grim, prophetic and weighted with bitter humour. “Holiday time, ladies and gentlemen! Holiday time, my friends across the Atlantic! Holiday time, when the summer calls the toilers of all countries for an all too brief spell from the offices and mills and stiff routine of daily life and bread-winning and sends them to seek, if not rest, at least change in new surroundings, to return refreshed and keep the myriad wheels of civilized society on the move.” Thus began the stockily built Englishman with the round face and the big cigar. As he talked, his light mood changed. He spoke of the “hush” which he said was “hanging over Europe.”

“What kind of a hush is it?” Churchill asked his radio audience. “Alas! It is the hush of suspense and in many lands it is the hush of fear. . . . Listen carefully; I think I hear something — yes, there it is, quite clear. Don’t you hear it? It is the tramp of armies crunching the gravel of the parade grounds, splashing through rain-soaked fields, the tramp of 2 million German soldiers and more than a million Italians going on maneuvers –yes, only on maneuvers! Of course, it’s only maneuvers -just like last year. After all, the dictators must train their soldiers. They could scarcely do less in common prudence, when the Danes, the Dutch, the Swiss, the Albanians and of course the Jews, may leap out at any moment and rob them of their living space and make them sign another paper to say who began it.”

Churchill continued in undisguised sarcasm: “Besides, these German and Italian armies may have another work of liberation to perform. It was only last year that they liberated Austria from the horrors of self-government. It was only in March they freed the Czechoslovak Republic from the misery of independent existence. It is only two years ago that Signor Mussolini gave the ancient kingdom of Abyssinia its Magna Carta. . . . No wonder the armies are tramping on when there is so much liberation to be done and no wonder there is a hush among all the neighbours of Germany and Italy while they are wondering which one is going to be liberated next. . . . This kind of guesswork is a very tiring game. Countries, especially small countries, have long ceased to find it amusing. Can you wonder that the neighbours of Germany, both great and small, have begun to think of stopping the game, by simply saying to the Nazis . . . : ‘He Who attacks any, attacks all. He who attacks the weakest will find he has attacked the strongest.’ That is how we are spending our holiday over here, in poor weather, in a lot of clouds. We hope it is better with you.”

Winston Churchill’s words paint a clear picture of the fear that haunted Europe that summer of 1939. They tell also of failure — failure to unite in time to discourage ambitious dictators. However, unity was forged into a mighty weapon by the heat of war and that unity crushed Italy, Germany and Japan. Plans for victory led to efforts to achieve world peace.

1. How did World War 2 begin?

2. How did the Allied powers defeat the Axis (aggressor nations)?

3. What attempts were made during World War II to achieve world peace?

1. How Did World War 2 Begin?

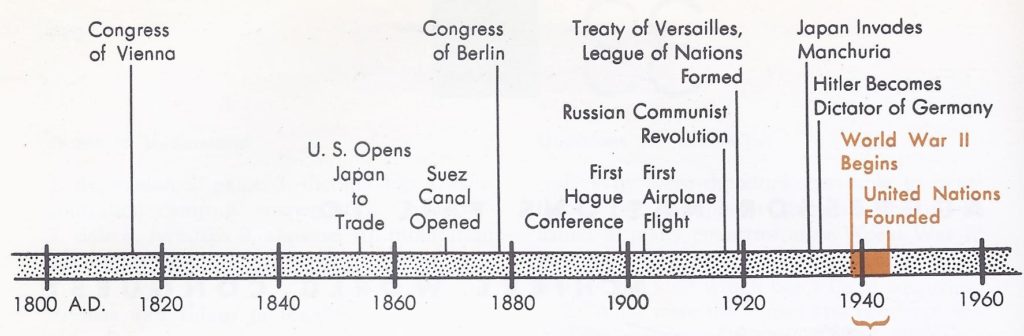

In order to understand the outbreak of World War II, we need to take a quick backward glance at the world picture during the 1920’s and 1930’s. Prospects for peace seemed fairly bright at the close of World War I. Germany had been disarmed. Russia was busy with serious problems at home. Great Britain and France wanted no more war. As the 1920’s wore on, to be sure, Mussolini was noisily asserting his demands, but it appeared unlikely that Italy would upset world peace. Japan was also beginning to reach into Manchuria, but Manchuria was far away and Japan’s aggression there did not seem very important to the nations of Europe and America. Meanwhile, the statesmen of the world had established the League of Nations and the World Court. They had signed international agreements which seemed to indicate that the world wanted peace and meant to have it.

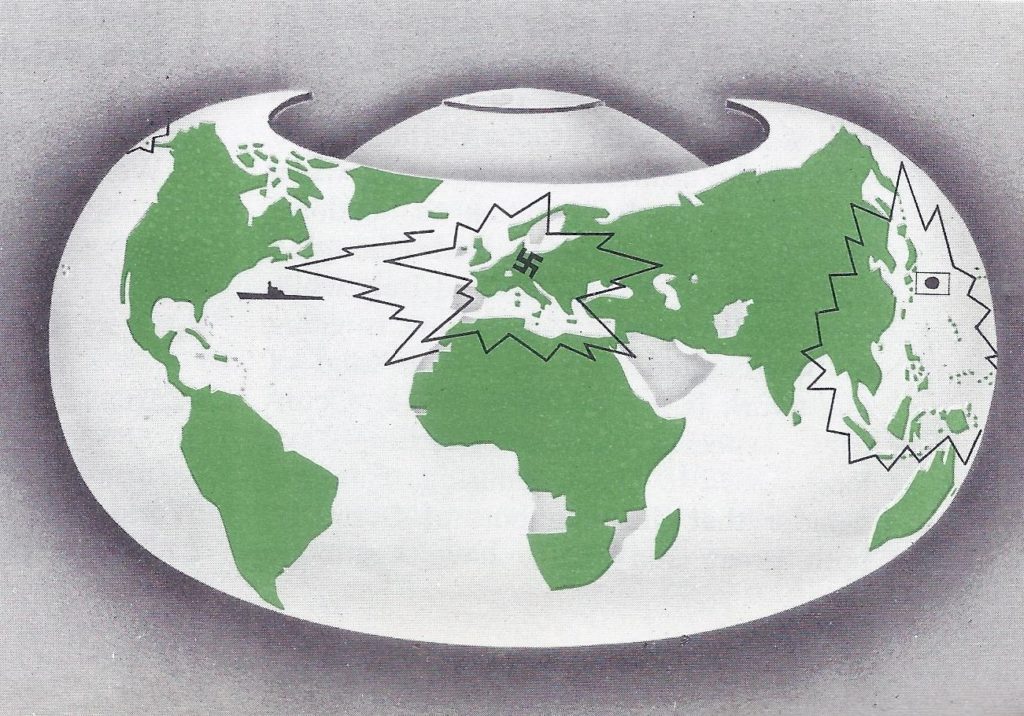

Aggressor nations began to threaten world peace. During the 1980’s hopes for world peace began to fade. Just as a few bullies with no regard for the rights of others can upset a neighbourhood, three aggressor nations upset the peace of the world. These three were Germany, Italy and Japan. Hitler and Mussolini, having established undisputed power over their own people, seized the territory of less powerful states. Meanwhile Japan, controlled by military leaders, made up its mind to become supreme in Asia. Japan talked of the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” This high-sounding phrase did not conceal Japan’s real ambition — to control the resources of China and all Southeastern Asia.

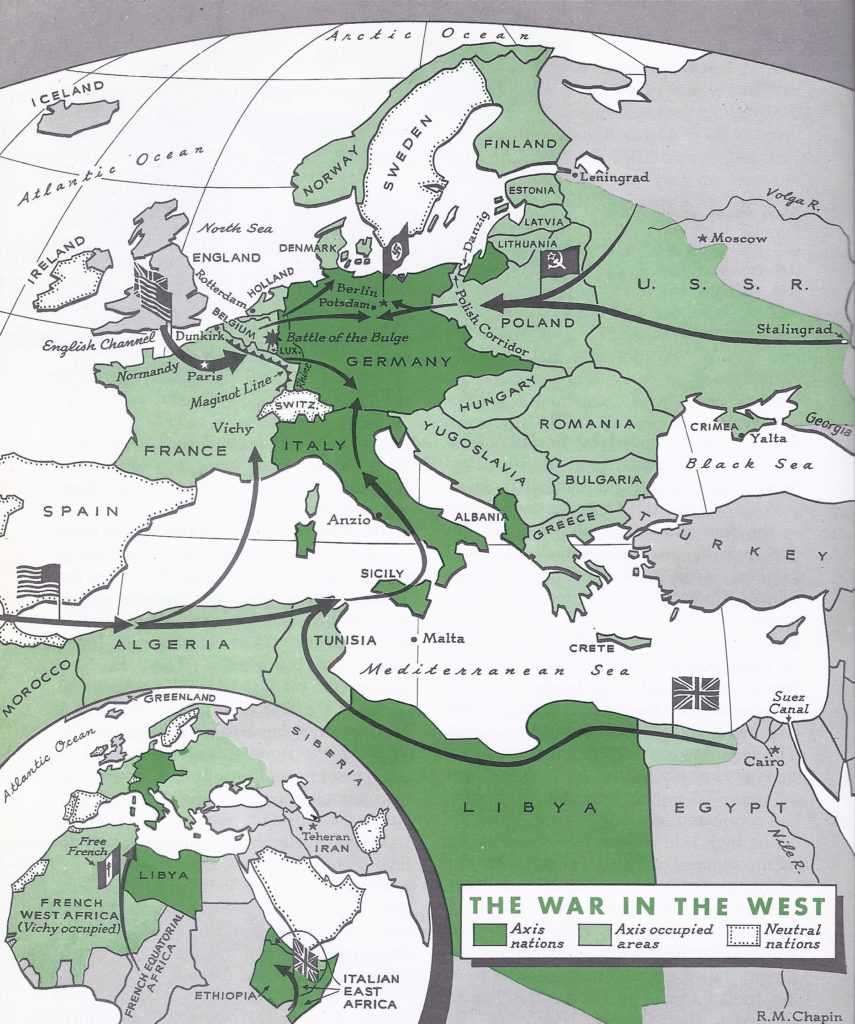

The aggressor nations drew together. Although Germany, Italy and japan each had its own special ambitions, they had some things in common. All were “have not” nations; that is, they lacked the land and natural resources they felt they should have. All wanted to change the existing world map by conquests that would give them great colonial empires such as those of the British and the French. Sooner or later all three left the League of Nations and made no pretense at peaceful dealings with the rest of the world. Japan had angrily quit the League because the League had scolded it for invading Manchuria. Germany dropped out when Hitler came into power and Italy left when the League protested against Mussolini’s attack on Ethiopia. In 1936 Germany, Italy and Japan drew together in what became known as the Rome-Berlin-Tokyo Axis, aggressor nations. (Axis in this sense means “alliance.”)

An arms-building race began. One of Hitler’s first acts after he came to power in 1933 was to re-arm Germany. He established universal military training, built a new navy and created a great air force. All these steps were violations of the treaties Germany had signed. Similarly Japan disregarded the limits on naval building agreed upon at the conferences held at Washington and London. Japan also built naval bases on the Pacific islands which it had won in World War I. With Germany, Japan and Italy setting the pace, the free nations began slowly and grudgingly to re-arm. By the late 1930’s an armaments race was under way in every part of the world.

The free world was slow to oppose aggressors. At first, Great Britain and France did not seem to realize the threat of the aggressor nations. Instead of fighting when Hitler started to expand his power, they tried to appease him. Did they believe that when the German dictator had taken Austria and the Sudetenland, he would be satisfied? Did they think he would turn eastward instead of westward? If Hitler did the latter, there might be war between Germany and Communist Russia which would not involve Great Britain and France.

By 1939, however, Great Britain and France were thoroughly alarmed by the aggressor nations. Hitler’s army was second only to Russia’s in size and probably superior to it in strength. Germany had a large navy and an air force which was second to none. Moreover, Hitler had strengthened his position with other nations. Italy and Japan had become his allies. Spain was friendly to him. Many of the smaller states of Europe dared not incur Hitler’s wrath by allying themselves with anyone who might oppose him.

Great Britain and France at last took action against the aggressor nations. Faced by these dangers, Great Britain and France finally abandoned their policy of appeasing Hitler. Great Britain passed a law requiring men to serve in the army, an action never before taken in peacetime. Great Britain also made alliances with Turkey, Greece, Romania and Poland, promising to aid them if they were attacked. France joined in these treaties and speeded up its efforts to re-arm. These last-minute efforts were offset in August 1939, however, by the stunning news that Russia had signed a treaty of neutrality with Germany!

Russia and Germany sealed Poland’s doom. This agreement with Russia cleared the way for the German army to strike at Poland. The new Poland created by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 was not to the liking of either Germany or Russia. Only the fact that these two countries distrusted each other had kept them from seizing Poland during the 1920’s and early ’30’s. Now a new partition could be carried out, with Hitler and Stalin rather than Frederick the Great and Catherine II doing the carving.

World War 2 began. At the end of the summer of 1939, Hitler demanded that Poland give Germany control of the Polish Corridor and that the free city of Danzig be restored to Germany. When Poland failed to agree to these demands, Hitler on September 1, 1939 ordered the German army to advance into the disputed region. France and Britain, loyal to their pledges, declared war on Germany two days later, World War II had started.

The world-wide struggle was to be in sharp contrast to the stationary trench warfare of World War I. On land, World War II was a conflict which featured sharp thrusts by swiftly moving motorized army units. In the air, it was a conflict marked by the dropping of parachute troops behind enemy lines and the destruction of cities and important military centres in bombing raids. On sea it involved huge airplane carriers, new kinds of landing craft and faster, deadlier submarines. As for civilians, World War II called for greater sacrifices and brought greater danger than any previous war in history.

After Poland fell, there was a lull in the fighting. The Poles were helpless in the face of the blitzkrieg (“lightning attack”) launched by the German tanks and planes. They fought bravely, as Poles have always done, but they had no chance. The British and French were too far away to send direct military aid. While German troops occupied the western parts of Poland, Russia occupied the east. Within a month free Poland disappeared.

Meanwhile, all was quiet on the border between Germany and France. Opposing armies were amassed behind fortifications, but neither Germany nor France wanted to move until more fully prepared. For months what was known as the “phony war” continued in the west.

Soviet Russia made the most of its opportunity. The Russians, though they had made a non-aggression treaty with Hitler, did not trust him. So they resolved to grab all they could while their hands were free. In addition to seizing eastern Poland, they moved against Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. These small Baltic states, created after World War I, were forced to give up naval bases to Russia and later were absorbed into the Soviet Union. Finland alone of the Baltic countries put up a valiant but losing fight. Russia also seized a part of Romania. By mid-1940, except for what was left of free Finland and the parts of Poland held by Germany, Russia had regained all the land it had lost in World War I.

Germany opened a full-scale attack on the west. With Poland wiped off the map and Russia busily occupied with land-grabbing, Hitler was free to strike at western Europe. In the spring of 1940 he launched a new lightning attack in an unexpected direction. Instead of moving against France and Great Britain, Nazi troops occupied neutral Denmark and swarmed into Norway. Hitler had the aid of fifth columnists, Nazi agents and sympathizers who helped betray the invaded country. The Norwegians resisted bravely, but their cause was hopeless. The help Britain and France gave was “too little and too late.”

Next Hitler swung his motorized divisions into Luxemburg, Belgium and Holland. The stubborn Dutch opened their dikes and flooded parts of their small country, but the waters that had stopped the Spanish in the 1500’s and the French in the 1600’s could not stop Hitler’s air force. German bombs wrecked Rotterdam in a senseless, vicious attack. Queen Wilhelmina and other members of the Dutch royal family fled to Great Britain.

The British and French sent forces into Belgium, but the fierce German plane and tank attack caused the Belgian king to surrender. The road to France now lay open to the Germans and the retreating British and French forces were in danger of being surrounded. Thanks to the British navy and air force, most of the exhausted British soldiers who fought their way to the beaches of Dunkirk were able to escape across the English Channel, but they had to leave their artillery and tanks in German hands.

France fell under the Nazi attack. The French had felt secure behind a chain of forts called the Maginot Line, but the German generals did not waste time in fruitlessly pounding these heavy fortifications. They by-passed the Maginot Line by going through Luxemburg, Belgium and Holland. Then the motorized German columns rolled swiftly southwestward across France, driving the French ground troops before them. From the air shrieked German Stukas, low flying planes that dive-bombed both retreating French soldiers and the bewildered homeless civilians who choked the roads.

The French government fled from Paris as the German war machine pushed relentlessly onward. The despairing French put their trust in aged Marshal Pétain, a hero of World War I, but the old man surrendered to the Germans almost at once. For the rest of the war Pétain remained head of unoccupied France with its capital at Vichy in the south. The white-haired, unhappy Pétain, however, obediently took orders from Hitler’s generals. Northern France was governed directly by Germany. For four bitter years the high-booted, helmeted troops of Hitler held Paris, the city where the French Revolution had preached the rights of man.

“Underground” movements sprang up in conquered countries. Many Frenchmen, like the Poles, Danes, Norwegians, Belgians and Dutch, did not surrender. When their countries were overrun, they established “governments in exile” in Great Britain. General Charles de Gaulle thought it a stain on the honour of France that his country had given up the fight. He proclaimed a “Free France,” which for several years controlled only a few African colonies. Meanwhile, in conquered countries, patriots went secretly to work. Try as he might, Hitler could not stamp out these resistance groups. They blew up bridges and wrecked trains. They buried explosives in roads and cut telephone and telegraph lines. They sheltered Allied airmen who had been shot down and helped them to escape. In spite of the fact that daily they faced arrest and severe punishment, these “underground forces” kept up their efforts.

Italy entered the war. Italy, which was neutral at first, might have remained so if Germany had not been so successful, but as the French forces collapsed under the German attack, Mussolini realized he might not share in the spoils of victory. So he declared war on tottering France in June 1940. The American President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, described Mussolini’s treacherous act in these words: “The hand that held the dagger has struck it into the back of its neighbour.” Mussolini also attacked Greece, an ally of Great Britain and started a desert war in North Africa along the frontier between Italian Libya and Egypt.

Actually the Italians achieved little by entering the war, even in the days when the Axis powers (aggressor nations) were winning. Egypt did not fall, because British forces pushed back the invading Italians. Greece was not subdued until Hitler came to Italy’s aid. Moreover, Hitler treated his Italian ally with contempt, making it painfully clear that Italy would be given only what Germany did not care to take.

Hitler launched a massive air attack on Great Britain. If Great Britain had been a part of the European continent, Germany might well have won the war. The British army had lost so much equipment during its retreat from Dunkirk that factories had to work for months to replace it. Meanwhile, the British had little with which to fight. What saved Britain was a streak of water so narrow that people have swum across it — the English Channel. Hitler, like Napoleon, had a large enough army to invade Britain but lacked control of the seas. So he planned to strike at Britain in a way Napoleon had never been able to do — through an air attack. The German air force was so much larger than that of the British that Hitler expected to humble the British speedily and force them to beg for peace.

In the meantime Winston Churchill had become prime minister of Great Britain. His courageous spirit inspired the British people to rally to the defense of their country against aggressor nations, even though he could promise them only “blood, sweat and tears.” When Germany unleashed the full fury of its air raids in the autumn and winter of 1940, no Englishman thought of surrender. The Royal Air Force, aided by the new and then top-secret device called radar, fought so successfully that Germany had to give up attacking in the daytime or from low altitudes. In a tribute to the British aviators, Churchill declared that never before in all history had “so many owed so much to so few.”

The Germans looked to the east. When his hopes of a quick victory over the British ended, Hitler hesitated. Should he try to invade Great Britain, even though he did not control the Channel or the North Sea? Or should he send his ground forces in an all-out attack on Russia? Hitler and his advisers believed that Russia, like France, could be crushed by a single knockout blow. By conquering Russia Germany would gain: (1) Russia’s broad wheat fields, (2) its oil wells near the Caspian Sea and (3) its other rich mineral resources. Furthermore, Hitler would no longer need to fear Russia’s treachery at his back. (Neither Hitler nor Stalin would let the fact that they had signed a treaty of neutrality stand in the way of attacking the other.)

Hitler strengthened his position in the Balkans. To pave the way for his attack on Russia, Hitler sent German forces into Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. He insisted that these countries become allies of Germany and Italy. German troops also overran Yugoslavia and Greece. The British troops which had been sent to check the German invasion of Greece were driven from the mainland to the island of Crete and from Crete to Egypt. The Fuhrer had a firm hold on the Balkans.

Hitler struck at Russia. Then in June 1941 Hitler suddenly launched an attack on Russia. At first his surprise move seemed likely to succeed, for the German columns rolled eastward into Russia almost on schedule. Soon they stood before the important Russian cities of Leningrad, Moscow, and Stalingrad, but these cities did not fall nor did Russia collapse, as Hitler had confidently predicted. Gradually resistance throughout Soviet Russia stiffened. The people of the Ukraine, who had first welcomed the Germans as liberators, were aroused to fighting fury by Nazi cruelty. Burning farm buildings and crops and destroying factories, the Russians fell back into the interior leaving nothing but “scorched earth” for the invading German armies. Hitler was to learn, as had Charles XII of Sweden and the Emperor Napoleon, that there was a vast difference between invading Russia and conquering it.

TIMETABLE WORLD WAR 2 – AGGRESSOR NATIONS (AXIS) ON THE OFFENSIVE

Germany invaded Poland, September 1, 1939

Germany suddenly invaded neutral Denmark and Norway, April, 1940

German troops swept through Holland and Belgium into France, May, 1940

France surrendered, June, I940

Germany invaded Russia, June, 1941

Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbour, December 7, I941

THE ALLIES HALT THE AXIS (AGGRESSOR NATIONS)

Massive German air attacks failed to knock out Britain, 1940-1941

US. Navy stopped Japanese advance at the battles of Coral Sea and Midway, May-June, 1942

Russians halted the German advance at Stalingrad, 1942

THE ALLIES ON THE OFFENSIVE

United States began Pacific “island-hopping” at Guadalcanal, August, 1942

American forces landed in North Africa, November, 1942

Allied landings forced Italy to surrender, September, 1943

Allied air attack on Germany reached a peak, 1944

Allies invaded the coast of France (D-Day), June 6, 1944

U.S. troops landed on Leyte in the Philippines, October, 1944

Germany surrendered (VE Day), May 8, 1945

United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, August 6, 1945

Japan surrendered (VJ Day), September 2, 1945

2. How Did the Allied Powers Defeat the Aggressor nations of the Axis?

The United States once again tried to stay neutral. From the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Americans had watched with painful interest the clash of armies and air forces in Europe. They remembered only too well that the United States had been drawn into Napoleon’s wars and World War 1. In these wars the United States had fought to defend its rights as a neutral. Hitler’s Germany, however, seemed a far more serious threat than either Great Britain or Napoleon in 1812, or the Kaiser’s Germany in 1914. Could America stay out of this second world war?

To many Americans the answer in the early days of the war seemed clear. If we sent no goods and lent no money to the warring nations and if we kept American-owned cargo ships out of dangerous waters, they argued, we could stay neutral. Let the warring nations buy only the supplies for which they could pay cash and carry them to Europe in their own vessels. In 1989, therefore, Congress put this “cash and carry” idea into effect.

Aggressor Nations (Axis) success led the United States to take positive steps. As the war progressed, American opinion underwent a change. By 1940 Germany seemed almost unbeatable. Belgium and Holland had been crushed under the Nazi iron heel. France had fallen. In these and other countries conquered by the aggressor nations (Axis powers), human freedom had disappeared. Hitler had not at that time attacked Russia, so Great Britain alone seemed to be holding out against the aggressor nations (Axis forces). Suppose Great Britain fell. Would the United States’ turn come next?

In 1940, therefore, Congress passed a law requiring military training for men between the ages of 21 and 35. It voted huge sums to increase the armed forces. Moreover, President Roosevelt turned over 50 of the old World War I destroyers to the British navy. In return the United States obtained naval bases on British islands in Atlantic and Caribbean waters. These outlying bases gave added protection against foreign attack.

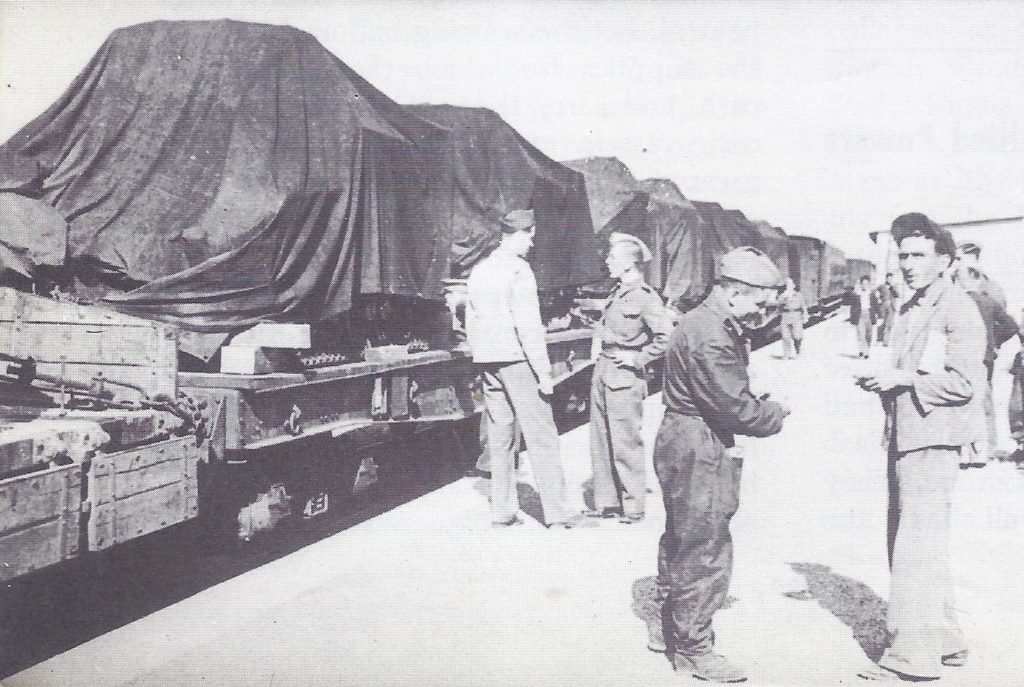

The American government went still further in 1941. Congress cancelled the “cash and carry” law and in its place passed the so-called Lend-Lease Act. This act allowed the President to sell, lease or lend war materials to any country whose defense was important to the safety of the United States. It soon became necessary to protect from German submarine attacks the supply line along which these Lend-Lease goods were being shipped. So American naval vessels went on patrol between their shores and Greenland and Iceland. American troops were also sent to guard those islands, two important stepping stones in the vital supply route across the Atlantic.

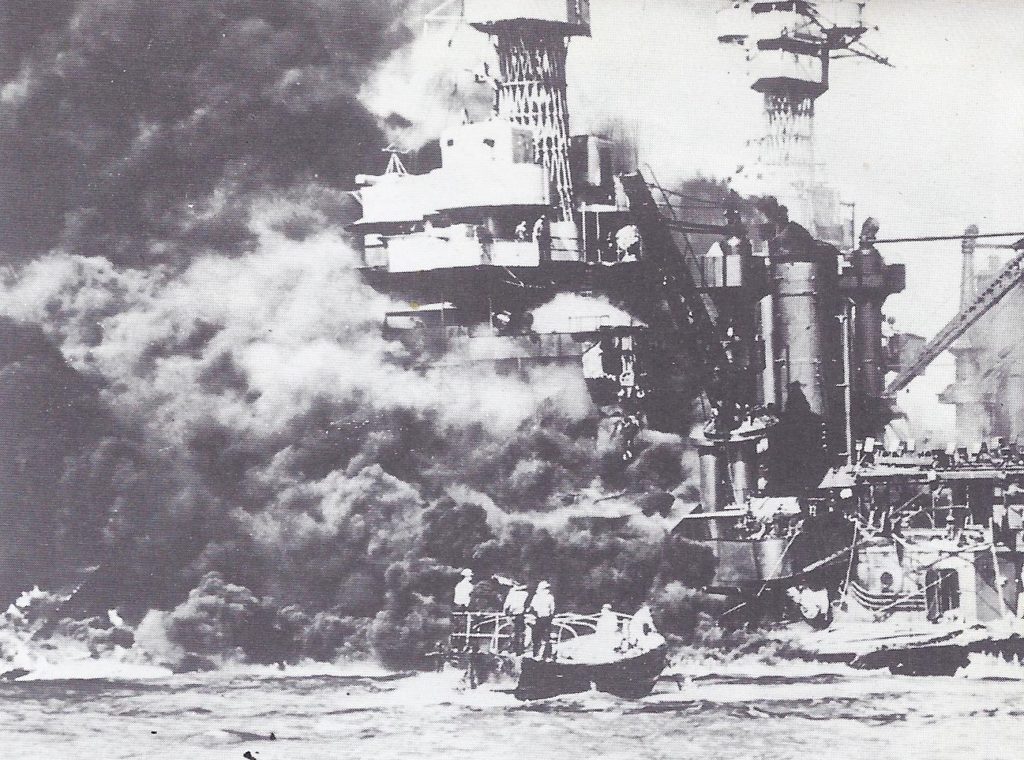

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour brought the United States into World War 2. To the average American late in 1941, indeed, the greatest threat to his country seemed to be Nazi Germany. But war first came to the United States from the opposite direction. While Germany and Italy had been expanding in Europe, the third aggressor nation (Axis power), Japan, had been busy in the Far East. As early as 1937 Japan had invaded China, a part of its ambitious plan to control all of east and southeastern Asia. Then as the war progressed, Japanese military leaders and businessmen came to believe that a golden opportunity was theirs if they seized it boldly. France and the Netherlands, now that they had fallen, could no longer protect their Asiatic possessions. Great Britain and Russia had all they could do to defend themselves in Europe. The American fleet had to patrol part of the Atlantic as well as the Pacific. Not in a thousand years could Japan expect to find the road to conquest so easy!

That is why Japanese planes streaked without warning over Pearl Harbour in Hawaii early on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941. The attack, which had been carried out while Japanese representatives were still talking peace in Washington, caused heavy loss of life and great damage to ships and planes. The United States replied by declaring war immediately against Japan. Shortly afterward, Germany and Italy joined Japan in making war on the United States.

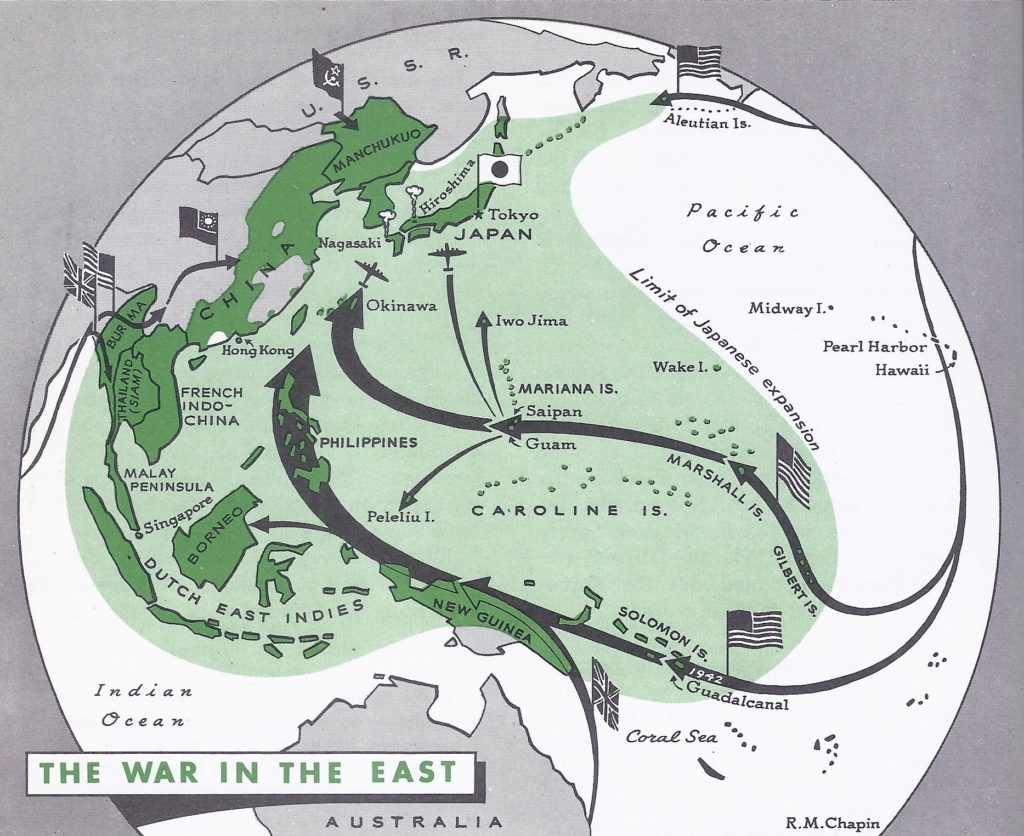

The Aggressor nations (Axis) gained on all sides. In the few months after the attack on Pearl Harbour, Japan took over French IndoChina, Thailand (Siam), the Malay Peninsula, the Dutch and British East Indies, the important British ports of Hong Kong and Singapore. Japanese forces overran the Philippines, finally overcoming the United States land forces that had heroically held out against them. The Japanese also conquered Burma and stood at the very gate of India. Not even Nazi Germany had conquered so many lands so quickly.

The high tide for the aggressor nations (Axis) was reached by the summer of 1942. The whole world seemed to lie at the feet of the war lords of Germany, Italy and Japan. Germany held most of Europe. German and Italian armies controlled North Africa, except for Egypt. Japan gripped the vast area from the Indian Ocean to the central Pacific and from the Aleutian Islands to the jungles of New Guinea. Japanese forces had also pushed into the heart of China. None of the great conquerors of the past — no Alexander, Caesar, or Napoleon seemed to have such power. The aggressor nations (Axis nations), however, had extended their lines too far. They were soon to find out that they had bitten off more than they could chew.

The turning point of World War 2 came in 1942. The tide had already begun to turn in the early summer of 1942 when the American navy won smashing victories in the Coral Sea, at Midway Island and in the Solomons. These battles cost Japan mastery of the Pacific. Then, in New Guinea and on Guadalcanal the Japanese were for the first time in the war driven from territory they had seized. Meanwhile, on the home front, Americans worked at top speed to supply goods not only for our own armed forces but for those of our Allies. The huge output of America’s farms and factories contributed greatly to final victory over the aggressor nations (Axis).

Far away on the Volga River, Russian troops halted a German army in the heart of Stalingrad. Now that their drive had stalled, the Germans began a slow retreat toward Poland. Meanwhile the Russians had set up new factories in Siberia to replace those in Europe which they had destroyed to keep them out of German hands. Moreover, Lend-Lease supplies from our America were reaching Russia in ever-growing amounts by roundabout routes through the Arctic Ocean and the Persian Gulf. Slowly but steadily Russian armies rumbled westward like a mighty steam roller.

The Allies attacked on a new front. The Allies also made important headway in North Africa. For many months the British had defended the island of Malta against furious air attacks. Malta was a key base in the central Mediterranean which helped the British to maintain their control of that sea. Then British forces under Field Marshal Montgomery drove veteran German troops headlong from Egypt and westward across Libya. Finally, in November 1942, an American army commanded by General Dwight D. Eisenhower landed in Morocco and Algeria. The Allied plan was to force the surrender of all German and Italian forces in North Africa. The aggressor nations (Axis) troops held out for several months, but in the end the combined American, “Free French,” and British forces triumphed.

The great event of 1943 was Italy’s surrender. From northern Africa allied British and American troops crossed the Mediterranean to the island of Sicily. From Sicily they struck at the Italian mainland. The struggle for control of the coast south of Rome was especially savage. In September 1943 the discouraged Italians turned against Mussolini and Italy surrendered. Though supposedly a warring nation no longer, defeated Italy was still far from being at peace. A large German army in the mountain ranges of central and northern Italy held on desperately until almost the end of the war.

Germany lost control of the air. Meanwhile Great Britain had become a vast air base from which swarms of British and American planes took off to bomb German industrial centres. This never ceasing rain of death and destruction by Allied bombers more than made up for the German air raids over Britain in 1940. It also marked the end of Germany’s control of the air. In a last desperate effort, the Nazis unleashed robot bombs and long distance rockets fired from German bases on the continent. These new weapons (named V-l and V-2) killed many British civilians, but they could not be aimed with sufficient accuracy to destroy factory centres and airfields.

In 1944, Allied forces landed in France. On June 6, 1944 came the day for which all peoples opposing the aggressor nations (Axis powers) had waited. This was “D Day,” when General Eisenhower, now Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces in Europe, sent his forces ashore in Normandy in northern France. As the giant guns of the combined American, British and Canadian fleets pounded German fortifications, as clouds of planes dropped bombs from the sky and cut German communication lines, as landing craft churned shore-ward bearing the first waves of Allied troops, General Eisenhower spoke these words over the radio:

Peoples of Western Europe: A landing was made this morning on the coast of France by the troops of the Allied Expeditionary Force. . . . I call upon all who love freedom to stand with us now. Together we shall achieve victory.

D-Day was the beginning of the end for Nazi Germany and aggressor nations.

France was liberated. The carefully laid Allied plans worked well. British and Canadian forces wheeled eastward and pushed back the German forces from the Channel shores. One column of American troops swung toward Paris; another force landed in southern France and drove northward. French patriots aided the Allied armies. In the face of this massive attack the Germans had to retreat. By the late summer of 1944 Paris was liberated. On toward Germany raced the Allied forces. The Germans launched their last great attack in Belgium at Christmas time, 1944. This was the so-called Battle of the Bulge, which slowed down the Allied invasion of Germany but did not stop it.

In 1945 Germany surrendered. As the Allied forces moved ever closer to Germany’s western border, the Russians on the east swept nearer and nearer. They had driven German troops from Poland, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary. Germany was caught in a huge vise which was steadily closing. Early in 1945, while the Russians continued their drive toward Berlin from the east, American forces crossed the Rhine and advanced into the very heart of Germany. Hitler, in black despair, killed himself in the ruins of bombed Berlin. By May 8, 1945 (known as VE, or Victory in Europe, Day) all that was left of Germany surrendered unconditionally.

Once the war in Europe was ended, important Nazi leaders were imprisoned. They were charged with having been responsible for the horrors committed in German prison camps where thousands of innocent civilians had been mass-murdered. In Italy, Mussolini was lynched by Italian guerrilla troops. In all the invaded countries traitors who had helped the aggressor nations (Axis) conquerors were punished for the aid they had given their nation’s enemies.

The Pacific advance continued. More slowly but just as surely, the tide had been turning against Japan. The war in the Pacific, however, presented special problems. First, island outposts which the Japanese had heavily fortified had to be taken. These islands could then be made steppingstones for an attack on the Japanese home islands. Second, the distances to be covered in the Pacific were immense. Ernie Pyle, a famous war correspondent, pointed out the importance of this fact in these words:

. . . at Anzio in Italy back in February of 1944, the Third Division set up a rest camp for its exhausted infantrymen; it was less than five miles from the front line, within constant enemy artillery range. But in the Pacific, they bring men clear back from the western islands to Pearl Harbour to rest camps — the equivalent of sending an Anzio beachhead fighter all the way back to Kansas City for his two weeks. It’s 3500 miles from Pearl Harbour to the Marianas, all over the water, yet hundreds of people travel it daily by air as casually as you’d go to work every morning.

By the end of 1944 American forces under General Douglas MacArthur had regained the Philippines. Meanwhile other American land and sea forces aided by their allies had won back considerable territory. In 1945, at a heavy cost in lives, Americans occupied the islands of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. From these bases it was possible to bomb Japan’s factories more easily. Hopeful Americans began to say that Japan would soon be defeated –perhaps in a year’s time.

The atomic bomb was used. The end came much sooner than was expected. Japan was ready to quit because of the terrific bombing which its cities were receiving. Japan wanted more favourable terms, however, than the unconditional surrender which the Allies demanded. Then on August 6, 1945, the first atomic bomb ever used in warfare was dropped on the city of Hiroshima. Three days later the second fell on Nagasaki. In each case a single bomb caused unbelievable loss of life and paralyzed a whole city. Two days after the destruction of Hiroshima, Russia declared war against already-beaten Japan and began an invasion of Manchuria to snatch some of the spoils of war.

All these blows were too much for the Japanese. They surrendered to General MacArthur on September 2, 1945, on board the U.S.S. Missouri in Tokyo Bay. American forces then moved into the city of Tokyo and the occupation of defeated Japan began.

World War II was far more costly than World War I. For the second time within twenty-five years the world and particularly Europe, had suffered a devastating war. World War 2 caused frightful death and destruction. To the millions of soldier dead, had to be added an even greater number of civilians. Many of these were victims of the bombing of great cities. Others had been mass-murdered in German concentration camps. Countless people starved to death after hostile armies had swept a country bare of food.

There was still another loss aside from that of life and property. Standards and values built up over the centuries seemed to have been lost. In modern times it had become the rule to begin a war with a formal declaration, to treat prisoners of war humanely and not to fire on ships or cities unless they were armed. During World War 1 these rules had been broken in individual cases, but in World War II most rules seemed to be disregarded. Germany and Japan began attacks not only without formal declaration of war but under cover of peace talks. They invaded neutral countries without excuse or apology. Prisoners were treated in a fashion which would have given pleasure to an Assyrian king of ancient times. Though the aggressor nations (Axis powers) set the example, both sides bombed undefended cities. Finally, the invention of the atom bomb opened up dread possibilities that in future wars air attacks might wipe out whole nations. It is no wonder, then, that men faced the future with fear as well as hope.

3. What Attempts Were Made During World War 2 Against Aggressor Nations To Achieve World Peace?

The Atlantic Charter was drawn up. Even before the United States entered World War II, thought was being given to the kind of peace toward which the nations opposing the aggressor nations (Axis) should work. In the Summer of 1941, a few months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt slipped quietly out of Washington. He and Prime Minister Winston Churchill met secretly on a United States warship off the coast of Newfoundland. At this secret meeting they agreed upon a general statement of peace aims which has since been called the Atlantic Charter. This famous document laid down several points upon which these two statesmen based their hope of a better world. Compare the Atlantic Charter with President Wilson’s famous Fourteen Points which served a similar purpose in World War I.

— No territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the people concerned.

— The right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live. . . .

— The enjoyment by all States, great or small . . . of‘access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world. . . .

— The fullest collaboration between all nations . . . with the object of securing, for all, improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security.

— A peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries and . . . assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want. . . . Such a peace should enable all men to traverse the high seas and oceans without hindrance.

— The abandonment of the use of force. . . . All other practicable measures which will lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments.

War leaders made peace plans. Even during the war years important programs for peace were discussed. On January 1, 1942, for example, the nations fighting against Japan, Germany and Italy agreed that they, as the “United Nations,” would make no separate peace with the aggressors.

War leaders also met on several occasions during the last three years of the war. President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill and Generalissimo (highest ranking general) Chiang Kai-shek, head of China’s Nationalist government, met at Cairo, Egypt. President Roosevelt, Prime Minister Churchill and Premier Stalin met at two conferences, one at Teheran in Iran and the other at Yalta, in the Crimea. At these conferences much of the discussion naturally had to do with military moves to win the war. Time was also spent on plans for dealing with defeated and liberated countries once the conflict was over. Many Americans have come to believe that the western leaders acted unwisely at the Yalta Conference when they promised certain territories to Russia in return for its aid against Japan.

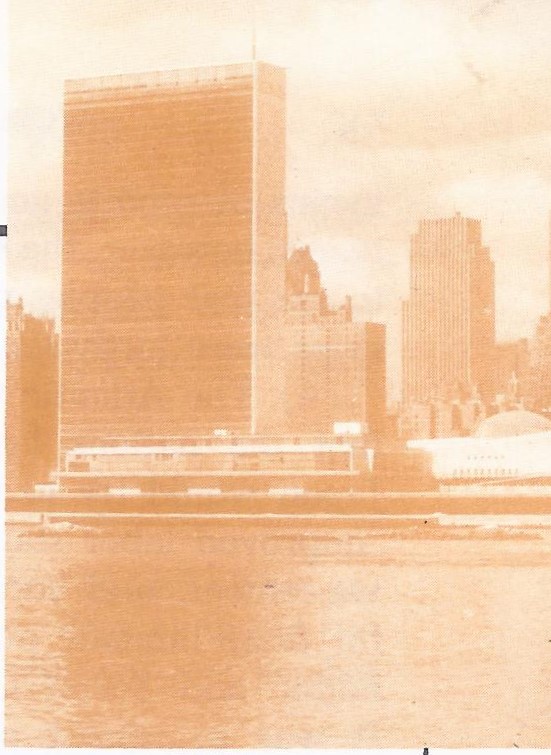

The United Nations Charter was written. By fall of 1944, when it was clear that the Allies were winning, a conference was held at Dumbarton Oaks, in Washington, DC. Representatives of the United States, Great Britain, China and Russia drew up plans for a world organization. Another conference was called for late April 1945 in San Francisco, to put these plans into definite form. Two weeks before the San Francisco meeting, however, President Franklin D. Roosevelt died and Vice President Harry S. Truman became President. It was President Truman who welcomed the hundreds of delegates on their arrival in San Francisco.

Hopefully the delegates went to work. All the nations, large and small, that had united against the tyranny of Germany, Italy and Japan, were represented. The war was still going on and the many nations seemed willing to co-operate. The result was the Charter of the United Nations, a constitution for a great new international organization of 51 countries.

What plan of organization did the United Nations Charter set up? The Charter of the United Nations made provision for the following units: (1) the General Assembly, (2) the Security Council, (3) the Trusteeship Council, (4) the Economic and Social Council, (5) the International Court of Justice and (6) the Secretariat. Let us see how these bodies were to be organized and what their responsibilities were.

(1) Each member nation was to be represented in the Assembly and each had one vote. The Assembly was to meet at least once a year, but its delegates could gather in a few days’ time in case of crisis. The Assembly could consider “any questions or any matters within the scope” of the United Nations Charter.

(2) The special responsibility of the Security Council was to settle international disputes peacefully. On the Council the five leading powers in 1945 — the United States, Russia, Britain, France and China were to have representatives at all times. Six other places in this all-important Council were to be rotated among other member nations. The representatives for these six places were to be elected by the Assembly for a two-year term.

(3) The framers of the United Nations realized there were people in Africa and parts of the Pacific area who were not ready for self-rule and could not provide for their own security. To take care of such regions, the United Nations Charter established a Trusteeship Council elected by the General Assembly. The Trusteeship Council was to assign responsibility for each region to a member nation. By means of reports and visits of inspection teams, however, the Council was to check to see that peoples placed under trusteeships were justly governed.

(4) The Atlantic Charter had pledged that the nations fighting Germany and Japan would try to secure for all people “improved labour standards, economic advancement and social security.” It was for these humane purposes that the Economic and Social Council was created. It was to consist of eighteen members elected by the Assembly.

(5) The International Court of Justice was to interpret and develop international law and to give opinions on disputes placed before it by member nations of the United Nations.

(6) To carry on the routine work of the United Nations its Charter provided for a Secretariat or permanent staff beaded by a Secretary General.

The UN differed from the old League of Nations. At first glance the new United Nations organization looked much like the League of Nations under another name. If you were to compare the two carefully, however, you would see certain differences. Instead of requiring all members of the Security Council to agree on an important action, only the agreement of the live permanent member nations and two others was needed. Any one of the five great-power members, however, could block important moves by a veto. The Council was to have a standing armed force of its own, although this provision has not been carried out. The General Assembly was to be assisted by an Economic and Social Council to consider questions of human welfare. The Economic and Social Council was in turn to be assisted by several special committees and agencies.

Another change was in the old system of mandates. These had been limited to former German colonies and to former Turkish possessions. Now any colony or territory could be placed under the “trusteeship” system of the new United Nations, if the country in control was willing.

United States joined the United Nations. The greatest difference, however, between the old League and the new United Nations was not in the rules: It was in the fact that the United Nations included all the great powers. This had not been true of the League of Nations, for America had not joined the League. Moreover, four important powers (Russia, japan, Italy and Germany) had dropped out of the League. In 1945, when the United Nations was formed, the five remaining great powers of the world, the United States, Great Britain, Russia, France and China — were all sitting together. The three aggressor nations (Axis powers) Germany, Italy and Japan — were defeated or toppling. Nearly all the world’s armed strength was within the new international organization. Whether these great nations could get along in peacetime as well as they had during the war remained to be seen.

Peacemaking was discouragingly slow. Preparing peace terms and settling the future of the defeated nations proved more troublesome than at the close of World War I. In fact, no major peace conference, such as the one held at Paris in 1919, ever took place.

In July 1945, following the surrender of Germany, British Prime Minister Attlee (Churchill’s successor), Premier Stalin and President Truman gathered at Potsdam, just outside Berlin, Germany. They met to plan (1) the final blows against Japan, and (2) control of defeated Germany. The conference agreed that a Council of Foreign Ministers, representing the United States, Great Britain, Russia, France and China, was to tackle the problems of drafting peace settlements.

During the next two years the Council of Foreign Ministers held several meetings. As a result, in 1947 peace treaties were signed with Italy, Romania, Hungary and Finland; but the Council made no progress toward arranging peace settlements with Austria or Germany. Relations between Russia and its war allies became very strained in the postwar years. Unable to reach any agreement on Austrian and German peace terms, the Council of Foreign Ministers ceased to hold meetings. So these two countries continued to be occupied, as they had since the end of the fighting, by foreign troops. Both Germany and Austria were divided into separate zones policed by American, British, French and Russian forces. Trouble frequently broke out between Russian soldiers and those of the Western Powers. Not until 1955 was an Austrian peace treaty signed. At that late date, Germany was still divided into two parts — a free democratic West Germany and a Communist-controlled East Germany.

The Charter of the United Nations

The purposes of the United Nations are:

To maintain international peace and security . . . to take effective collective measures for the prevention and removal of threats to the peace, and for the suppression of acts of aggression . . . and to bring about by peaceful means . . . settlement of international disputes . . .

To develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples . . .

To achieve international cooperation in solving . . . problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in . . . encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion . . .

To be a centre for harmonizing the actions of nations in the attainment of these common ends. . . .

Tags: liberation , underground forces , radar , “have not” nations, aggressor nations , fifth columnists, governments in exile , “cash and carry” , blitzkrieg , phony war , scorched earth , Churchill , Pétain , de Gaulle , Teheran Conference , Yalta Conference , General Assembly , Security Council , Trusteeship Council , Axis powers , Maginot Line , F . D. Roosevelt , Montgomery , Eisenhower , Lend-Lease Act , Battle of the Bulge , MacArthur , Atlantic Charter , United Nations , Free France ,1939, December 7 1941 , June 6 1944 , May 8 1945 , September 2 1945 , Aleutian Islands , Coral Sea , Midway Island , Nagasaki , Dutch East Indies , Solomon Islands , Guadalcanal , Malta , Dunkirk , Crete , Stalingrad , Iwo Jima, Okinawa , Vichy , Pearl Harbour , New Guinea , Hiroshima