When the United States entered World War 1, President Wilson had stated that America’s aim in taking up arms was “to make the world safe for democracy.” The first results of the war seemed to show that this attempt had succeeded. Old empires had crumbled and new republics had risen from their ruins. Democratic constitutions were adopted in most of the countries which the war had created or remodeled, but this apparent victory for democracy did not last, even though kings did not return to power as they had in 1815 after Napoleon’s defeat. What happened was that the kings were replaced in many countries by military adventurers or by ambitious political party leaders. This change occurred chiefly in those countries where the people had had little or no experience in self-government. Much of the world’s history from 1918 to 1939 was made by these dictators.

Russia was the first major country to go through profound changes. Even before Germany was defeated, you will remember, Russia had overthrown its all-powerful Czar. The Communists, who soon seized power, set up what they called the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” or rule of the workingmen. Actually, power in Russia was centred in the hands of a few top leaders. The Communists established a system in which Western ideas of personal liberty, democracy and private ownership had no place. What is more, they tried to force Communist ideas on other countries. By their ruthless control over Russia’s millions they changed Russia from a defeated and disorganized country in 1918 to the greatest threat to the free world by the late 1940’s.

How did all this come about? Just as we found that the causes of World War I lay rooted in conditions which had been developing for fifty years before the struggle began, so what happened in Russia during the 1800’s and early 1900’s helps to explain more recent changes in that country. Here we will find answers to the following questions:

1. Why did Russia fail to make more rapid progress during the 1800’s?

2. What circumstances led to the Communist dictatorship in Russia?

3. What way of life did the Russian Communists establish?

1. Why Did Russia Fail to Make More Rapid Progress During the 1800’s?

Russia expanded into a great power. From a small trading post at Moscow and expanded into the great country of Russia. During the 1700’s, under such rulers as Peter the Great and Catherine II, Russia not only continued to expand but became an outstanding example of an absolute monarchy. Though Napoleon conquered most of Europe, his attempt to invade Russia ended in disaster and paved the way for his final defeat. When the rulers and statesmen of Europe gathered at Vienna in 1814-1815, therefore, Czar Alexander I was one of the influential figures at the conference. No ruler appeared so firmly fixed on his throne as the Russian Czar.

Russia added new areas to its empire during the 1800’s. By the close of the century Russia occupied half of Europe and the northern half of Asia, or about a sixth of all the land surface of the earth. Russia’s population had soared from about 40 million in 1800 to about 133 million a hundred years later and was greater than that of any other European nation.

Other nations feared Russia’s growing might. Rudyard Kipling, the English poet of imperialism, was much worried about Russia. In one of his poems he described Russia as “the bear that walks like a man.” What he was referring to, of course, was the brute strength that this undeveloped country possessed. Throughout the 1800’s most European nations feared the might of the Russian Empire. British and French statesmen brought their countries into the Crimean War to preserve the Turkish Empire as a barrier against Russia. British statesmen continued through the 1800’s to regard Russia as their chief rival. Even Chancellor Bismarck of Germany seemed to fear Russia more than any other foreign nation.

The Russian Bear was not as powerful as it appeared. With its huge territory and growing population, Russia in the 1800’s could have been the greatest power on earth, but this was not the case. Russia lagged behind most Western powers in government, industry and the condition of its people. Let us see how backwardness in these respects weakened Russia.

1. Backwardness in government. Long after the other great powers gained constitutions and parliaments, the Russian czars continued to govern as absolute monarchs. Since one man could not possibly be everywhere and do everything, the ruling czar had to rely on a great body of officials. These officials were not interested in reforms which would limit their authority as well as the czar’s. Moreover, they were often inefficient and corrupt. The army was the pet of the czars and more care and money were spent on it than on all the rest of the government. Yet the Crimean War in the 1850’s and the Russian-Japanese War in the early 1900’s revealed much graft and inefficiency in the Russian army.

2. Underdeveloped industry. Industry had not moved forward in Russia as it had in most Western countries. To be sure, Russia possessed rich natural resources, mines and factories, but the Industrial Revolution affected Russia much later than it did countries such as Britain and the United States. In fact, during all but the closing years of the 1800’s, Russia remained very largely a country of farmers. Nine-tenths of the people were peasants, using old-fashioned methods and primitive tools. The standard of living was low and a poor harvest might cause tens of thousands of deaths from starvation.

3. Lack of regard for human welfare. In Russia there was no large, prosperous middle class of manufacturers and businessmen as there was in France or in Great Britain. Except for a fairly small class of nobles and wealthy landowners, Russia was a land of uneducated, downtrodden peasants and until the 1860’s millions of these peasants were serfs, poorer and more miserable than the serfs of western Europe during the Middle Ages. Russian serfs belonged to the land on which they were born. They possessed almost no rights of their own and were required to perform many duties for their masters. Landowners could punish the serfs cruelly.

So far we have been speaking of the Russian people themselves. Within the vast Russian Empire, however, there were also large numbers of Finns, Poles, Jews and other minority groups. These people were not only denied the freedom to rule themselves, but they were treated with such mistrust that they felt like outcasts. In fact, failure to make contented subjects of non Russian groups was another of Russia’s weaknesses.

There were serious obstacles to reform. Why was Russia backward? The truth is that the strong winds of constitutional government, democracy and social reform which swept over much of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars were hardly felt in Russia. To be sure, some of the officers who had fought in these wars came back to Russia with ideas of liberty; and a few nobles began to discuss and write about these ideas. Societies of army officers, scholars and liberal-minded nobles proposed such reforms as (1) doing away with serfdom, (2) giving land and individual rights to peasants and (8) limiting the czar’s powers, but such reforms were opposed by the majority of nobles and landowners, who did not wish to lose their special privileges.

Moreover, the peasants were too downtrodden and ignorant to have or to understand liberal ideas. For centuries these miserable people had been so used to absolute authority that they took it for granted. Some reforms were accomplished during the 1800’s, but they did not greatly alter conditions. Each brief period of half-hearted reform was followed by a long period of repression. It was as if, for every step upward on a steep mountain trail, Russia slipped back half a step.

The Russian czars were absolute rulers. From the days of its earliest leaders, the dukes of Moscow, Russia’s rulers had been all-powerful. Peter the Great and Catherine the Great had required a blind obedience from their people. So also did Catherine’s son, Paul, who became czar while the French Revolution was spreading ideas of the rights of man. Paul had no use for such notions as liberty and equality. “Here is your law,” said he, pointing to himself. This mentally unbalanced tyrant was assassinated by a group of his officers.

Alexander I talked about reform. As a ruler, Alexander I was a great improvement over his father, Czar Paul. He believed in the aims of the French Revolution and talked grandly of giving freedom to Russia. In fact, other rulers at the time thought his views were dangerously liberal, but Alexander I turned out to be more of a dreamer than a doer. He meant well when he talked of giving Russia a constitution, of freeing the serfs and of increasing the number of schools and colleges, but the practical problems of working out such reforms seemed to baffle him. Foreign wars took much of his attention and as he grew older, he became less interested in liberal ideas. Except for some educational reforms and greater self-rule for his unhappy Polish subjects, Alexander I did little to improve conditions for his people.

Nicholas I was an enemy of reform. Nicholas I, who became czar in 1825, had no use for liberal ideas. As a military leader, he demanded unquestioning obedience from his soldiers; as Czar he expected the same attitude on the part of his other subjects. At the very beginning of his reign a group of reform-minded officers and nobles started a revolt in order to obtain a constitution. The rebellion was quickly put down and its leaders executed or exiled, but the revolt convinced Nicholas that Russia should be sealed off from Western ideas. Foreign visitors were halted at the Russian border and if they seemed likely to spread dangerous ideas they were refused admission. Foreign books were treated in the same fashion. A careful watch was kept on schools and teachers to stamp out liberal ideas. Magazine articles and books had to be passed by government censors before they could be published. Discussion of political affairs was forbidden. To enforce all these restrictions, a special body of police was organized. Under Nicholas 1, then, every effort was made to keep Russia and its people untouched by outside ideas.

Demands for changes in Russia continued. To most Russians, downtrodden as they were, the new regulations meant little, but there was a small group of educated Russians willing to risk imprisonment, exile and even execution for their liberal ideas. This group continued to work for reform by meeting secretly and by writing poems, stories and essays that set forth new ideas. More and more of them favoured doing away with serfdom and getting rid of the class of noble landowners. This reform movement, to be sure, failed to reach the great mass of uneducated Russian peasants, but it kept the spirit of revolt alive. Later on, the socialistic theories of Karl Marx gained headway in Russia.

Alexander II freed the serfs. Alexander II became czar in 1855, just as the Crimean War was coming to a close. Russia’s defeat in this conflict had shown its weaknesses as a military power. Russians everywhere began to grumble about inefficiency, corruption and the special privileges enjoyed by certain classes. Alexander II had the good sense to realize that some reforms must be made. To Russian nobles who were blind to the need for change he gave this warning: “Better that the reform should come from above than wait until serfdom is abolished from below.” What he meant, of course, was that the government should do away with serfdom before a revolution did so.

By the Czar’s orders Russia’s millions of serfs became free during the 860’s. (Slavery was abolished in the United States at this time.) They were no longer subject to the authority of their former masters but were given certain rights as Russian subjects. They were also permitted to keep as their own property the cottages, livestock, tools and a small part of the land they had been using.

Alexander ll carried out other reforms. Alexander’s reforms did not stop with freeing the serfs. He revised Russian laws and the system of courts. He also took steps to increase local self-government. Councils were elected in country districts. Each council was expected to levy taxes, build and repair roads and provide local hospitals and schools.

Alexander’s reforms failed to satisfy the people. The Russian people soon found that these changes did not bring about all the improvements they had hoped for. Consider, for example, the abolition of serfdom. Once they were freed, the serfs had expected to receive without cost the same lands which they had been working for the landlords. Instead land was given to local villages to be divided among the peasants. The peasants were dissatisfied with the amount of land they received and complained that selfish landlords kept the best land for their own use. Furthermore, in order to repay the landlords for the land they had lost, the government burdened the peasants with a heavy special tax that was to be levied for 49 years.

Alexander’s other reforms fell short of what had been expected. The new local councils were far from democratic. Although all classes were supposed to be represented in them, the large landowners usually were in control and while the new laws permitted open trials by jury in most kinds of cases, persons who wanted to make changes in the government could still be secretly whisked off to exile in dismal Siberia.

Alexander II faced new troubles. At best, Alexander’s interest in reform had been half-hearted. When discontent persisted inspite of the abolition of serfdom and other reforms, he became discouraged. He was particularly upset by unrest among the Poles. Soon after the Congress of Vienna, the Poles within Russia had been granted a constitution. Although they were subjects of the Czar, they had their own Parliament, their own officials and their own army. When revolutions swept over Europe in 1830, the Poles took up arms to gain complete independence. The revolt was quelled and the Poles were brutally punished. Many Polish families were broken up or driven into exile. The Poles, lost their constitution and Parliament and were governed directly by Russian officials. When Alexander II came to power he relaxed these harsh conditions, but only to have the defiant Poles rise in revolt again (1868). Due to these disappointments, Alexander’s interest in reform cooled. Hatred of the Czar in turn caused his subjects to resort to new acts of violence.

Reform was at a standstill in the late 1800’s. Two other czars ruled Russia during the 1880’s and 1890’s. Neither of them favoured reform. Alexander III, like Nicholas I, made no secret of his dislike for Western ideas. Russia had its own background and traditions, he declared and should not copy other countries. Alexander III adopted a policy of crushing democratic ideas and practices. The peasants had less voice in the local councils than before. Books and newspapers were censored and schools closely regulated. Those who opposed the government suddenly felt the heavy hand of the Czar’s secret police on their shoulders and disappeared.

Toward his non-Russian subjects Alexander III adopted a policy of “Russification”; that is, he attempted to stamp out all national feeling and to make them Russian in language and viewpoint. This policy made it appear that only Russians were trusted by the Czar and caused the large number of non-Russians to resent his rule. The Finns were forced to adopt Russian as their official language. Polish schools were forbidden to use or teach the Polish language. Of all groups, the Jews suffered the most under Alexander III. They were restricted in the places where they could live, the work they could do and the schooling they could receive. With the encouragement of the Czar’s officials, terrible persecutions called pogroms took place, in which many Jews were massacred.

Nor did conditions improve under Czar Nicholas II. He continued the policies of his father, Alexander III, but had little ability or strength of character. These weaknesses, helped to bring about the downfall of the czarist government.

Russia produced great scholars, writers and composers. Although Russia during the nineteenth century was backward in many ways, a small number of educated Russians showed remarkable creative ability in literature, science and music.

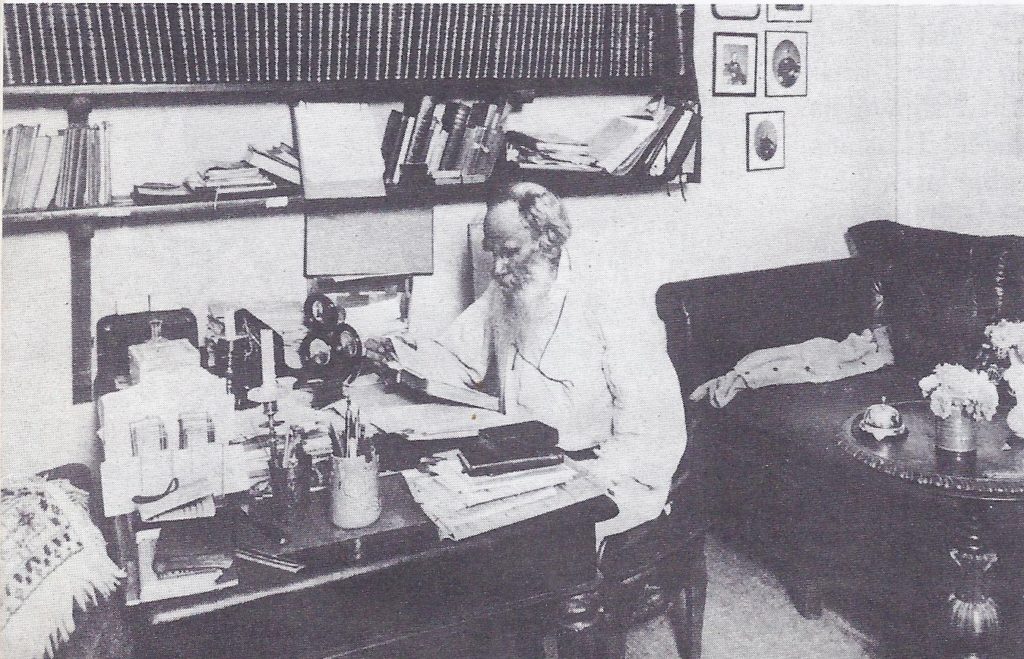

1. Literature. A number of Russian authors, of whom Count Leo Tolstoy was the most famous, wrote novels. War and Peace, in which Tolstoy condemned war, is one of the great books of the world. The stories of Anton Chekhov and Ivan Turgenev have been translated into many languages.

2. Science. The experiments of Ivan Pavlov established important principles in the study of psychology, the science of human behaviour. In chemistry and other science courses you may have heard the name Dmitri Mendeleev. Mendeleev discovered an important law which helps chemists to tell how elements can be combined.

3. Music. The works of Russian musical composers of the late 1800’s became well known, too. You have read of Tschaikovsky’s “1812 Overture,” a picture in music of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow. Rimsky-Korsakov was another Russian composer whose music is often heard. Rachmaninoff, a composer and one of the greatest pianists of all time, played before thousands of Americans in the early 1900’s.

So we see that the tyrannical rule of the czars did not stifle creative art in Russia. There was, of course, some censorship of literature, but authors often disguised political writings by using the form of fiction. Science, drama, music and other arts had not yet fallen under the shadow of dictatorship.

2. What Circumstances led to the Communist Dictatorship in Russia?

Revolutions are usually a long time in the making. Except for brief periods of reform under Alexander I and Alexander II, the Russian czars of the 1800’s either ignored the rising discontent among their subjects, or used strong-arm methods to crush it, but just as rising waters after heavy storms may in time cause a weakened dam to give way, the rising forces of discontent finally burst forth in Russia in the early 1900’s and destroyed the czarist government. What new forces caused this revolution?

Reformers began to advocate the use of violence. During the early 1800’s, a small group of educated Russians had tried to improve conditions. They hoped to transform their country by peaceful methods into a modern nation where people would enjoy individual freedom, self-government and better opportunities. They studied and discussed what was going on in other countries. These attempts at moderate, peaceful reform got nowhere, some reformers talked of using stronger methods. They began to preach violence and terror. So they organized secret societies, printed books and magazines urging revolution and plotted to kill government officials. Most radical of all were people that wanted to do away with government entirely. Advocates of no rule at all are known as anarchists. Alexander II himself was killed by anarchists who threw a bomb into his carriage.

The Industrial Revolution brought changes in Russia. Near the end of the 1800’s, much later than in most Western countries, the Industrial Revolution began in Russia. Russian mines produced large quantities of coal and iron. Russian factories turned out steel and textile goods. Sugar refineries and flour mills grew in number. Production of oil was stepped up so that by 1905 about one-fourth of the world’s supply came from Russian oil wells. Much of the money needed for the development of industry came from foreign investors.

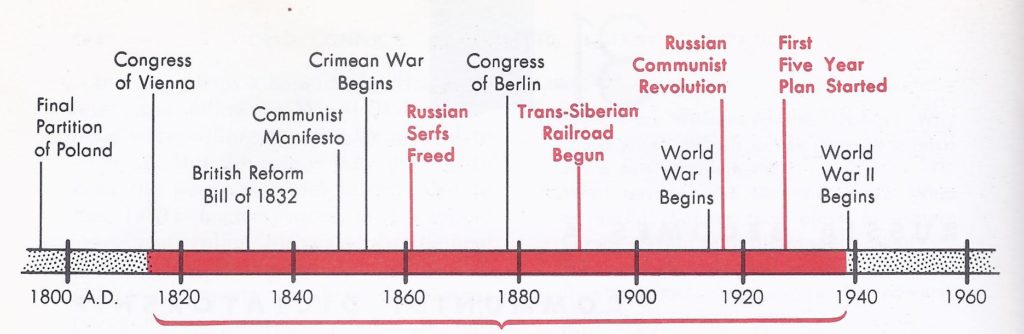

The Industrial Revolution also brought improvements in transportation. Railroad lines were built, though the government soon took over privately owned and operated lines. In 1892 the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway began. Some ten years later a single-track line had been pushed through from Moscow to Vladivostok on the Pacific coast, a distance of nearly 6000 miles. By the late 1890’s there were more than 40,000 miles of railway in Russia.

The Industrial Revolution brought other changes, too. A growing and prosperous middle class began to appear, composed of businessmen, factory owners and professional people. Peasants flocked to mines and factories for jobs. As in other countries, the growth of industry resulted in a shift in population. Between 1850 and 1900 the percentage of Russians living in cities and towns doubled. In spite of the growth of the towns and cities, however, Russia remained very largely a country of farmers. In 1900, eighty-seven percent of the Russian people still lived in rural districts, whereas in our own country at that time only about sixty-one percent were rural dwellers. In general, these Russian peasants were poverty-stricken and discontented. They could not raise enough food because their farming methods were backward and they were not allotted sufficient land.

The Industrial Revolution brought other changes, too. A growing and prosperous middle class began to appear, composed of businessmen, factory owners and professional people. Peasants flocked to mines and factories for jobs. As in other countries, the growth of industry resulted in a shift in population. Between 1850 and 1900 the percentage of Russians living in cities and towns doubled. In spite of the growth of the towns and cities, however, Russia remained very largely a country of farmers. In 1900, eighty-seven percent of the Russian people still lived in rural districts, whereas in our own country at that time only about sixty-one percent were rural dwellers. In general, these Russian peasants were poverty-stricken and discontented. They could not raise enough food because their farming methods were backward and they were not allotted sufficient land.

The new industrial classes added to the discontent in Russia. The new classes created by the Industrial Revolution swelled the chorus of protest in Russia. (1) The new middle class resented the power of the landowners and the corruptness of the government. Its members favoured moderate changes which would limit the czar’s power, increase self-government and bring about social reforms. (2) The new workers in mines and factories, however, had more extreme ideas. They were forced to live in overcrowded, unsanitary dwellings and they laboured long hours for low wages. Due to these government restrictions, they were not able to improve their conditions through labour unions. Unlike the reform-minded nobles and the middle class, therefore, city workers demanded radical changes. Some took up the socialist doctrines of Karl Marx and looked forward to the day when workers themselves would own and operate all mines, factories and businesses.

The Russian-Japanese War fanned the flames of discontent. A wiser ruler than Nicholas II would have understood what was happening and taken steps to stem the rising tide of protest among his subiects. Nicholas stubbornly refused to surrender any of his power or to undertake reforms. Instead he sought to turn the attention of his subjects from conditions at home by making war on Japan in 1904. The Russian people, however, showed little enthusiasm for the war. The war disclosed not only the weakness of the Russian army but the graft practiced by many government officials. As news spread of one defeat after another, resentment grew stronger and led to revolt.

Revolution broke out in 1905. One Sunday in January 1905 a large crowd led by a priest gathered outside the Czar’s palace in St. Petersburg. Its purpose was peaceful — to present demands for reform, but Russian soldiers opened fire on the defenseless men and women, many of whom were killed.

“Red Sunday,” as it was called, aroused the whole country. To the protests of the city workers and the middle class was added a strong demand among the peasants for land reform. They wanted the land that was held both by the government and by large landowners divided up. Many Poles, Finns and Jews also joined in the rising tide of revolt. Sailors of the fleet mutinied and peasants burned down the houses of big landowners. A general strike of all groups of workers brought activities throughout Russia to a standstill.

Nicholas made some concessions. The frightened Czar now agreed to certain reforms. He promised his subjects such rights as “freedom of person, freedom of conscience, of speech, of meeting and of association.” He also agreed that there should be an elective assembly, or Duma; and stated that no laws would be adopted without the approval of this legislature.

Outwardly the Czar’s power was now limited, but actually Nicholas’ reforms turned out to be largely empty promises. New worker uprisings were harshly crushed, as before. The first two Dumas met for a short time only. In each case the Czar dismissed the delegates because they demanded sweeping reforms. A later Duma, controlled by more conservative delegates, adopted a number of reform measures, but these were too moderate to satisfy most of the people. All that Nicholas had done was to postpone trouble.

The Revolution of 1905 had failed chiefly because the army had remained loyal to the Czar and because the different groups in revolt — the middle class, the city workers and the peasants — were not united. The seeds of revolt were still present. The people were only waiting for a new chance to overthrow the hated czarist government. That opportunity came during World War I.

RULERS OF MODERN RUSSIA

The Czars

Alexander I led Russia to victory over Napoleon and gained new influences in European Affairs, 1801 – 1825

Nicholas I organised secret police and tried to shut Russia off from Western ideas – 1825 – 1855

Alexander II freed the serfs and attempted reforms, but was assassinated, 1855 – 1881

Alexander III, a reactionary, oppressed minority groups in Russia, 1881 – 1894

Nicholas II resisted democratic reforms and was overthrown by revolution in World War I – 1894 – 1917

Revolutionary Leaders

Kerensky led a moderate government which was overthrown by communists, March – November, 1917

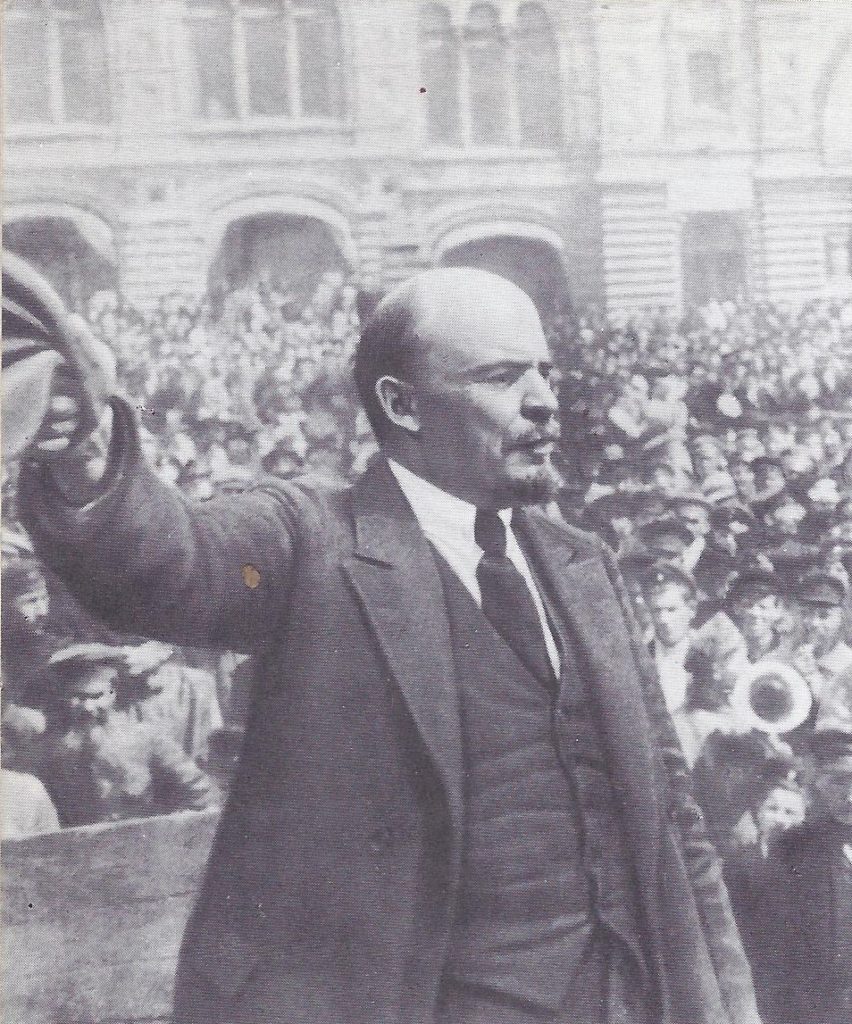

Lenin set up a Communist dictatorship, 1917 – 1924

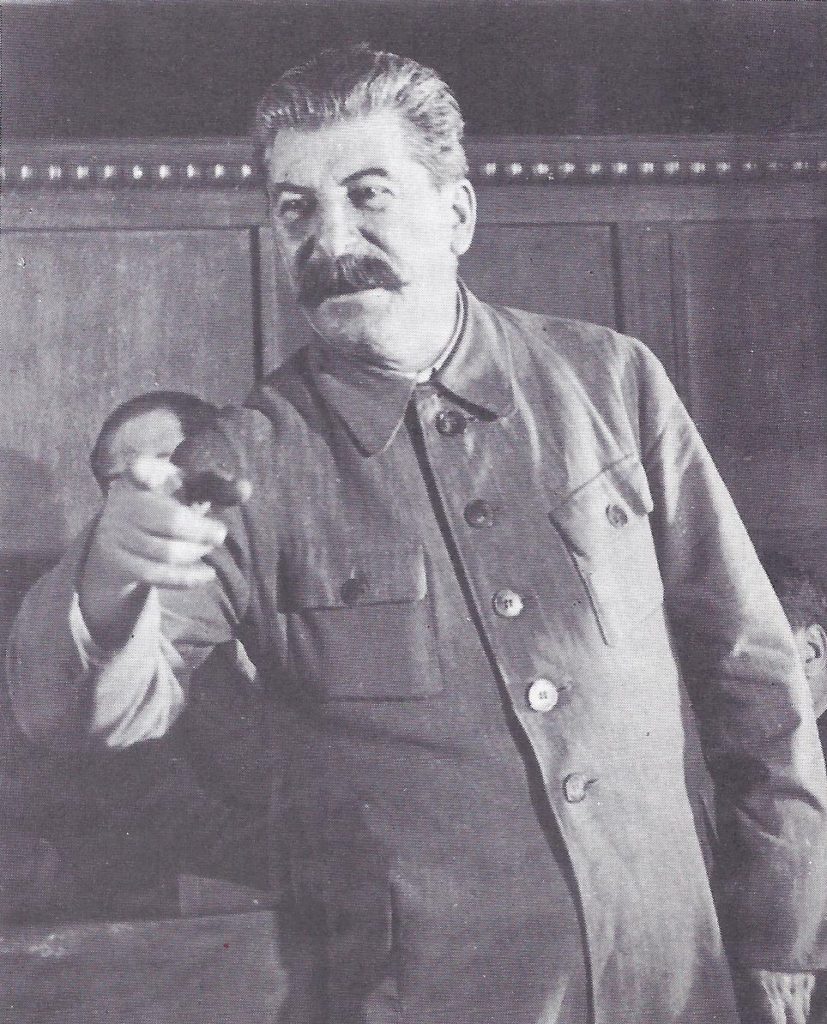

Stalin eliminated Trotsky and other rivals, strengthened the dictatorship and industrialized Russia, 1924 – 1953

World War I brought an end to rule by the Romanovs. As the defeats suffered by the poorly led and badly equipped Russian armies killed any enthusiasm which the Russian people might have had for World War I. Whispers, some true and some false, blamed these defects on inefficiency or even treason. Nicholas himself was patriotic, but the people mistrusted the generals and statesmen who surrounded him. Moreover, his wife, the Czarina, gave her confidence to a self-styled monk named Rasputin, who claimed that he had magic powers to help the sickly heir to the Russian throne. Fearful of Rasputin’s influence, a group of courtiers murdered him, but the people’s faith in the government was further shaken.

Early in 1917 matters came to a head. Strikes and food riots broke out in the cities. Called out to restore order, the soldiers instead backed the rioters and disarmed their own officers. Without the support of the army, Nicholas had no choice but to give up his throne. He and his family were imprisoned and later taken to Siberia, to which so many of the victims of czarist tyranny had been banished. In 1918 the members of the royal family were brutally shot to death. So ended the 800-year rule of the Romanov czars.

A provisional government was set up. The provisional or temporary government set up in place of czarist rule was a middle-of-the-road government. It favoured the adoption of a constitution which would give citizens more rights. It pardoned thousands of persons who had been imprisoned or exiled because they had opposed the czar. It also granted self-rule to Poland and Finland and did away with anti-Jewish laws. Furthermore, it proposed to continue fighting on the side of the Allies. The most famous leader of this provisional government was Alexander Kerensky.

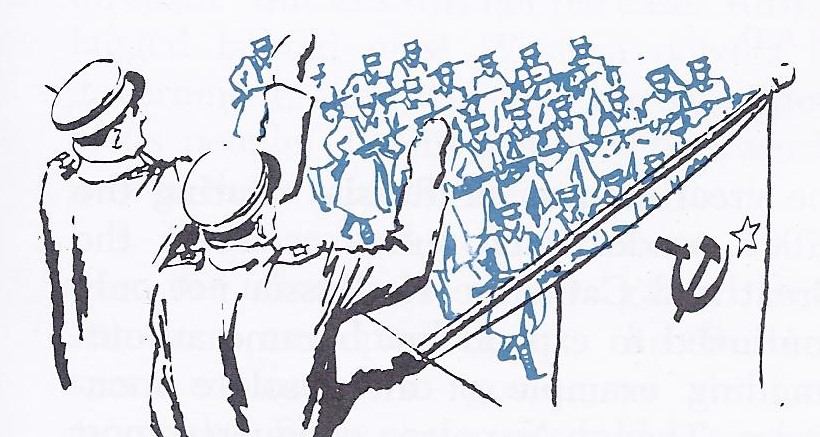

The Communists took over. The provisional government lasted only a few months, from March to November, 1917. It delayed putting through the land reforms the peasants desired and did little to relieve the lot of city workers. Moreover, the provisional government failed to recognize the growing unwillingness of the people to continue the war. More military defeats increased discontent among war-weary Russian soldiers and Russians at home. This was just the chance that a group of radicals had been waiting for. They belonged to the so-called Bolshevik or Communist Party, led by Nikolai Lenin and Leon Trotsky. The Communists were not satisfied merely with a more democratic form of government; they wanted to bring about sweeping social and economic changes. When revolution had broken out in March 1917, local councils or soviets were formed, consisting of workingmen, peasants and soldiers. In many cities the soviets had more real power than the provisional government. At first these bodies were controlled by moderate men who wanted both democratic freedom and social reforms, but the Bolsheviks rapidly took control of them. The Bolsheviks now argued, let the soviets be the government! “All power to the soviets” became the Communist slogan.

In November 1917, the Bolsheviks seized control of the government and proclaimed a so-called Soviet Republic, a dictatorship of the working classes. The leaders of the provisional government were arrested or forced to flee for their lives. Once in control, the Communists proceeded to make peace with Germany by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, but Russia had not yet achieved peace, for there was civil war in many parts of the country. Two or three years more of fighting took place before all the groups opposed to the Bolsheviks were overcome and Russia was united under soviet rule.

War and revolution had wrecked Russian industry and left the country a prey to famine. The Bolsheviks therefore undertook to re-organize Russia according to their own ideas.

3. What Way of Life Did the Russian Communists Establish?

Russian Communists promised democracy but made themselves dictators. Many dictators have openly gloried in their personal power. The Bolsheviks who snatched control of the Russian government, on the contrary, tried to conceal their absolute control under glowing promises. They posed as friends of liberty and democracy, but they put off giving real freedom to the people, saying that personal liberty and actual control of the government were luxuries that people would get later. “Just wait until we get our power established and our program under way,” said the Communist leaders. The road to the “people’s democracy,” they declared, lay through a “dictatorship of the proletariat [working class].”

Though it was not possible to make millions of people a dictator in the usual sense of the word, Russian workingmen were favoured at the expense of other classes. Workingmen were supposed to have the vote, whereas people in the upper and middle classes had no voice at all in government. Moreover, the town workers ranked higher than the peasants because the votes of town workers were permitted to count for more than those of the peasants. Outwardly, at least, the Russian government was based on soviets or councils made up of worker, peasant and soldier delegates. Each village had a soviet. Village soviets elected district soviets, district soviets elected regional soviets and so on up. At the top there was an All-Russia Congress of Soviets. This body in turn chose a Central Executive Committee and a cabinet or Board of Commissars.

Leaders of the Communist Party ruled Russia. This outward form of government was of very little importance. The various soviets did little more than approve the laws and decrees laid before them by the Communist Party. Numbering less than 2 million members, the Communist Party made up the only legal party in Russia. In theory the members of the Communist Party elected and controlled their leaders. In practice, however, all power came to be concentrated in the hands of a few leaders at the top. These party leaders controlled not only the Communist Party, but also the Soviet government, the army and an increasingly powerful secret police force.

Twice the constitution adopted by the All-Russia Congress in 1918 was changed. (1) The first change (in the 1920’s) created a federal state, called the Soviet Union or Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Besides Russia proper the Union included other states, such as the Ukraine, White Russia and the Caucasus republics, as well as large but less important states in Asia. Each of these republics had its own set of soviets and some degree of local home rule. By 1940 the Soviet Union included sixteen republics. (2) A new constitution in 1936 promised greater personal liberty. It also gave the farmers equal voting rights with the town workers and introduced the secret ballot, but, as before, only members of the Communist Party were allowed to take part in politics and only one list of candidates was presented to the voters. No one was allowed to criticize the Soviet government. For these reasons, therefore, the new constitution in 1936 in no way decreased the power of the Communist Party chiefs or increased the real power of the people. In fact, the system of terror, backed up by the threat of forced-labour camps, became even worse.

The first Communist dictator was Lenin. Lenin had master-minded the revolution which brought the Communists into power in November 1917. His influence was so great that, as long as he lived, his decisions prevailed. After his death he remained a national hero. Every year Russians by the thousands visit his tomb in Moscow’s Red Square.

Lenin had come into power at a time when Russia had suffered defeats at the hands of Germany. There was unemployment and discontent on all sides. During the next few troubled years Lenin bent his efforts toward holding and strengthening his power. He used Russia’s new revolutionary army to crush outbreaks against the Communists. The “red” soldiers reconquered land in the Ukraine, Caucasus and central Asia. Foreign nations that had sent aid to the Russian enemies of Lenin and the Communists finally abandoned these efforts. Lenin’s secret police, more ruthless and efficient than the Czar’s, spied on all those who were suspected of opposing the government. Under a reign of terror tens of thousands were put to death and almost two million people fled the country.

During these same years Lenin and the Communists put into effect sweeping changes. All land was declared the property of the government. Peasants were allowed to use as much land as they actually worked themselves, but they had to give a large part of their crops to the government. Mines, railways, factories, banks, stores and business companies all were taken over and operated by the government. In other words, the government abolished private ownership of the means of production. It also took over control of all foreign trade.

Lenin established a “New Economic Policy.” These changes were extreme and came too rapidly for a country already badly shaken by war and revolution. Factory production slumped and goods became scarce. Transportation broke down and food supplies dwindled. The peasants were unable to buy manufactured goods and were hard pressed by the government’s demands. So they took to raising only enough food for their own needs. In 1921 and 1922, when there was a severe drought, the peasants had no surplus food to fall back on and several million died of starvation.

Under these conditions Lenin relaxed his Socialist programs for the time being. He announced a New Economic Policy (NEP) which permitted peasants to sell their crops at a profit after paying their taxes to the government. Private persons could again carry on retail trade and run small factories. Big business, however, was carried on solely by the government or under government management. The government urged foreigners to invest money in Russia, introduced more efficient methods in factories and increased wages for skilled workers. Under NEP both agriculture and industry improved fairly rapidly. By 1927 production was back to the pre-World War I level.

The second Russian dictator was Stalin. Meanwhile, in 1924 Lenin died. For a short time the government was controlled not by one man but by a group of Communist leaders. Soon a new dictator forged to the front. He was known as Joseph Stalin, meaning “man of steel.” This was an appropriate name for this grim dictator, though actually Stalin was not his real name. Unlike, Lenin, Stalin was not a Russian by nationality; he came from the mountainous region of Georgia in the Caucasus.

Stalin quarreled with Trotsky and most of the other widely known party leaders. A few, like Trotsky, he forced to leave Russia; others he removed from power and later had many of them killed. Stalin and his aides used the word “liquidate” (to dispose of) to describe various methods of getting rid of enemies. Their places were filled with obedient followers of his own policy. Trotsky, one of the original leaders of the Communist Party, was “liquidated” (murdered) in Mexico after years of exile.

Trotsky and Stalin had, of course, been rivals for supreme power in Soviet Russia. There was also another reason for their falling out. Trotsky felt that the Communists should work to bring about a Communist revolution immediately throughout the world. This point of view was in line with the teachings of Karl Marx, who had preached that the rule of the working class could be successful only if it was practiced in every country, but Stalin refused. His first goal was to build up a strong Russia; he would use Russian power later to force other nations to accept communism.

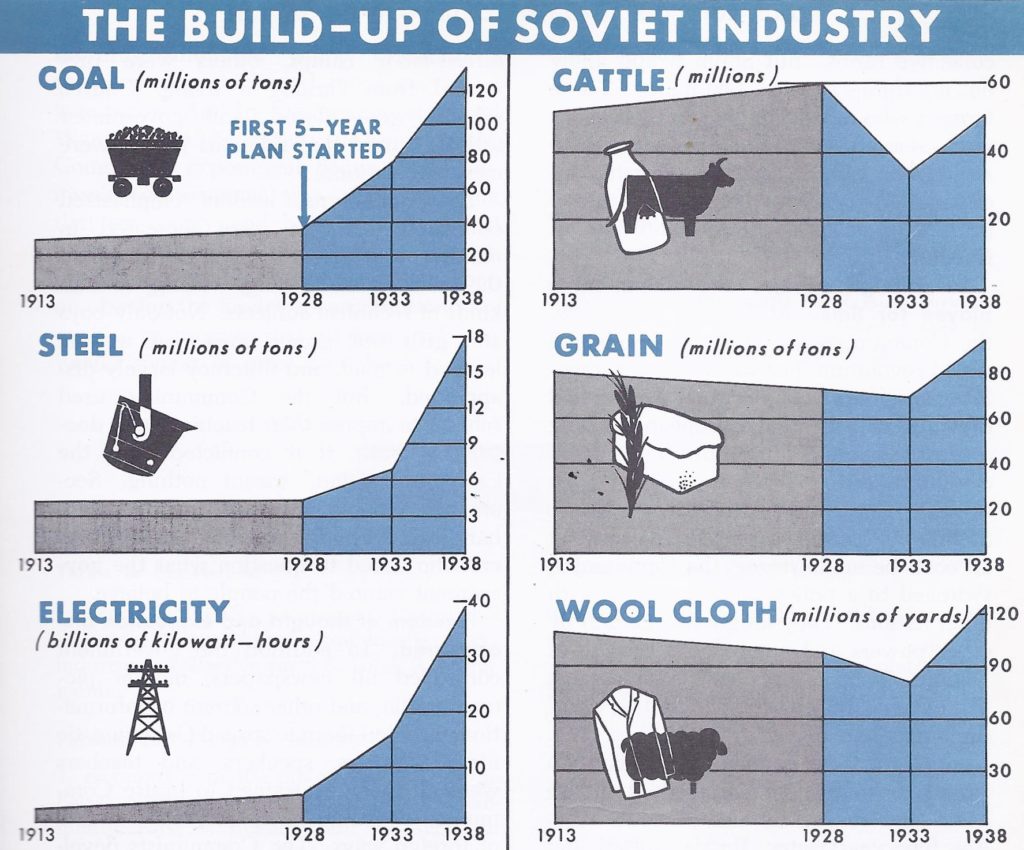

Stalin launched plans to strengthen Russian industry. Although the Industrial Revolution had begun in Russia by the late 1800’s, that country was still backward industrially compared with other leading powers. Stalin believed the first step toward making Russia strong was to build up its heavy industries. So he launched a so-called “Five Year Plan” (1928-1983) to industrialize Russia. A second Five Year Plan was announced in 1933 and a third was under way when World War II broke out. The Russian people were expected to bend all their effort toward reaching the goals set up for the Five Year Plans. Though this meant hardship and a continued low standard of living, glowing promises of better and more prosperous times at the end of each Five Year Plan were dangled before their eyes.

In the first Five Year Plan particular attention was paid to building up basic industries. In the words of one historian, what Russia aimed to do by this Plan was “to create a gigantic modern factory system, capable of large-scale production.” Machines were introduced to do much of the work previously done by animal or human labour. Mines, railways, steel mills, electric power plants and factories grew in number and in output. However because Russia lacked skilled engineers and business leaders, many were brought in from the United States and European countries. The second Five Year Plan aimed to increase the amount and variety of goods for consumers. Both Plans called for a huge increase in farm produce to feed the increased number of industrial workers and also to swell exports to foreign countries. These exports would help to raise money for new industries, so the people were told.

The Five Year Plans brought serious problems. It is true that under these Five Year Plans Russian industry expanded rapidly, but there were serious drawbacks. Although production in the mines and the quantity of factory goods increased, quality was not good. Instead of rising as the Communist leaders had promised, the standard of living declined. Many goods as well as farm products were strictly rationed, or parceled out. High quotas, or fixed requirements of quantities of goods to be produced, were set up for each factory. Managers and workers who failed to meet these quotas were severely punished.

Farmers in particular were discontented. To increase farm output, the peasants were required to give up their own plots of land and join together in collective farms on which whole villages worked, using modern machinery. Farmers and particularly the more prosperous ones called kulaks, resented the system of collective farms, but Stalin would allow no interference with his plans. Those farmers who refused to give up their farms were starved out, executed, or sent to slave-labour camps. In short, Russia’s industrial progress was bought at a heavy price in personal suffering and loss of freedom.

In foreign affairs the Communists played for time. At first, as you know, the Communists hoped for an immediate world revolution, just as the French revolutionists, more than a century earlier, had dreamed of a general European uprising against the rule of kings, but the walls of capitalism did not fall at the first blast of the Communist trumpet and because Stalin was convinced that Russia must at all costs be made strong, the Communists switched to a policy of compromise with other nations. They sought recognition by other powers and entered the League of Nations. They also played the same game of “balance of power” which the czars’ diplomats had played from 1815 to 1914. In 1891 Russia had allied itself with France from fear of Germany; it did so again and for the same reason in 1935, but four years later, Russia shifted and made a secret agreement with Nazi Germany.

Communist dictators tried to reshape Russian thinking. So far, the Communists established political and economic control. They set up a dictatorship of workingmen under the control of the Communist leaders. They abolished the system of private property and minutely planned the economic life of the people. Communist rulers did not stop there. They undertook to change the thinking and the very spirit of the Russians. They sought to destroy religion, which they said was the “opiate [mind destroying drug] of the people.” Not all churches were closed, but worship was generally frowned on. The Orthodox Church lost the special privileges which it had enjoyed for centuries under the czars. Many clergymen were sent to forced-labour camps, others were prevented from earning a living. Church schools were closed and government schools taught that religious beliefs were mere superstition.

The Communist leaders emphasized education. Schools were increased in number and great stress was placed on the teaching of reading, writing and all kinds of technical subjects. Not only boys and girls but grown men and women learned to read and illiteracy largely disappeared, but the Communists used schools to impose their teachings and doctrines. Truth, if it conflicted with the Communist “line,” meant nothing. Secondary schools and universities were handicapped by the weeding out of teachers who dared to question what the government wanted the people to believe.

Freedom of thought and expression disappeared. In addition the government controlled all newspapers, motion pictures, radio and other sources of information and used them to spread Communistic ideas. Writers, speakers and teachers were all carefully trained to praise Communist ideas and plans and to be critical of foreign ways. The Communists developed the methods of propaganda (making the people believe what the leaders wanted) to a fine art. They followed the old rule of tyrants throughout history — that if your lies are big enough and repeated often enough, many people will believe them, but in spreading propaganda the Communists had the advantage of new and modern means of communication.

The main object of the Russian Communist government at home had been to modernize Russia quickly. It hoped in a very brief span of years to transform the typical Russian from an easy-going peasant into a serious, highly trained industrial worker. Definite progress in industrializing Russia had been made, but with a fearful loss of human life, freedom and happiness. Energetic but scornful, intolerant young Communists replaced the older and more easy-going generation and by the opening of World War II in 1939, twenty years after the Communist experiment began, the Communist government was still promising that prosperity and happiness were just around the corner. All that the Russian people had to do, they said, was to keep on obeying the Soviet government and accepting its promise that all their problems would sooner or later be solved.