There he sat in the great hall in the German city of Worms. His bright eyes and wide forehead gave him an air of distinction. You would not quickly forget that face. Before him was gathered an assembly of high ranking nobles and churchmen from many parts of Europe. For this man was Charles V, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Archduke of Austria, ruler of the Netherlands and half of Italy, as well as King of Spain and master of Spain’s vast possessions in the New World. Yet Charles, who belonged to the famous Hapsburg family of Austria, was only 21 years old when he came to Worms in the year 1521. He had been elected Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire only two years before and he hoped to settle many pressing problems in conference with the assembled notables.

Perhaps it was just as well for the young monarch that he could not look into the future. Perhaps it was fortunate that he could not foresee some thirty-five years of struggle within his empire. He did not know that he would be fighting French men and Italians and Turks, as well as the Protestants of his own empire. Nor is it likely that in 1521 Charles V would have believed that the time would ever come when he would gladly and freely hand over his vast powers and lands to others.

Yet after a reign of 37 years Charles told another group of nobles: “I am no longer able to attend to my affairs without great bodily fatigue. . . . The little strength that remains to me is rapidly disappearing. . . . In my present state of weakness, I should have to render a serious account to God and man if I did not lay aside authority, as I have resolved to do.”

Charles sought peace and quiet for his remaining years within a monastery. There the one-time ruler of most of western and central Europe and much of the New World found time for the things he really loved and found restful: reading, music and the other arts.

We read about the beginnings of kingdoms in Europe. We learned how kings clashed with nobles and powerful churchmen in their efforts to gain political power. There is more of such conflicts, but you will also find out about struggles for power among rulers of different nations. We will learn how the loosely-knit Holy Roman Empire suffered from conflicts within and from attacks by ambitious kings and peoples from without. We will read not only about Charles V and his son Philip II, but of the great Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus. We will also find answers to the following questions:

1. What happened to the empire of Charles V?

2. How did the Thirty Years’ War delay the growth of strong states in central Europe?

3. Why did certain countries in central and eastern Europe shrink or disappear?

4. How did people in western and central Europe live in the mid-1600’s?

1. What Happened to the Empire of Charles V?

Royal rivalries influenced Europe’s development. Much of the history of Europe in the 1500’s and 1600’s is the story of rivalries between the heads of various states. Differences over religion played an important part in this story. But underlying most happenings was the determination of ambitious rulers (l) to increase their lands, their wealth and their power and (2) to prevent any one state from becoming all-powerful in Europe. This second idea, the attempt to maintain a balance of power, often accounted for strange alliances. It led states which had been enemies at one time to become friends on other occasions. It even caused Catholic French kings to side with Moslem Turks against Holy Roman emperors! Balance of power, as we will read ahead, continued to be a guiding principle in the relations between European powers. Indeed, it plays an important part in world politics to this day.

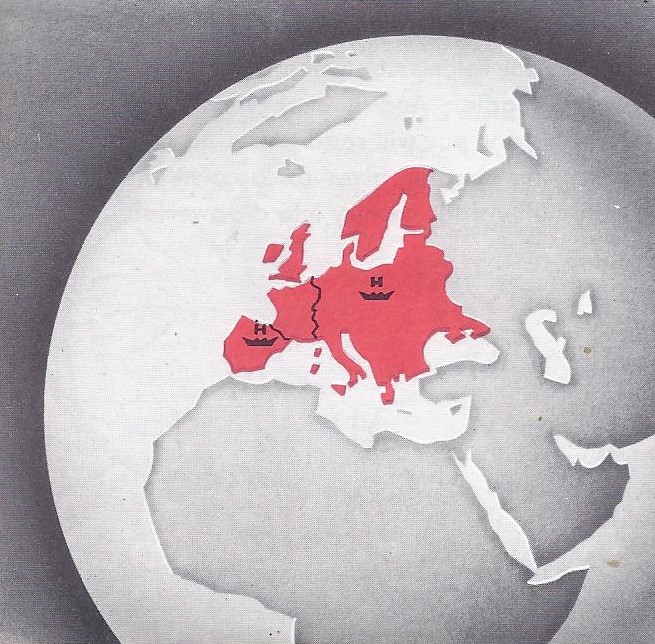

Royal rivalries caused constant warfare and warfare brought not only great suffering but many changes in the map of Europe. England, France and Spain grew into powerful unified kingdoms. Holland became an independent republic. The realm of Charles V, ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, was too large and made up of too many different peoples to hold together.

Charles V ruled an immense empire. No other European king or emperor between the time of Charlemagne (about 800) and Napoleon (about 1800) ruled so great an empire as did Charles V. Charlemagne, won half of his empire by hard fighting; and Napoleon, as we will read later, won all of his by military power. Charles V got most of his lands by peaceful means. From the royal family of the Hapsburgs he inherited Austria. From other royal relatives he obtained Burgundy and the Netherlands. Still other relatives presented Charles, not only with Spain but also with Spain’s possessions in Italy and the New World. His brother Ferdinand was elected king in Hungary and also in Bohemia (roughly the same area in central Europe now called Czechoslovakia). The people in Hungary and Bohemia wanted a ruler strong enough to protect them from the warlike Turks of southeastern Europe. They were willing to accept Hapsburg rule, harsh as it often was, in order to make themselves more secure. Charles himself was chosen Holy Roman Emperor by the Electors, who as history recalls included some of the more important German rulers.

Charles V’s realm lacked unity. At its height Charles’ empire was so large that it included several present day European countries, but there were reasons why this sprawling realm did not hold together.

(1) Its peoples spoke many different languages; German, Dutch, Flemish, French, Italian, Spanish, Czech or Bohemian, Magyar (Hungarian) and several others.

(2) Differences in customs and past history (they had often fought each other) kept the peoples of the empire apart.

(3) Religious difference divided them, too. Northern Germans were mostly Lutheran Protestants, but in southern Germany, Austria and Bohemia the people were largely Catholic. In the Netherlands many of the Dutch became followers of the Protestant Calvin, while the Flemish remained Catholic. Such differences in language, race and religion, as well as old hatreds and fears, led to misunderstandings and quarrels.

(4) The size of this empire and the problems of communication within it also stood in the way of real unity. In those days, of course, there were no telegraph or telephone lines, no radio, no railroads, automobiles or airplanes. News travelled no faster than horse and rider could proceed over wretched roads. Slow travel and communication increased the ruler’s problems. Emperor Charles would be called away from beating back the Turks on the far borders of Hungary to fight French forces invading Italy. Then the Emperor might have to force his way through the blizzards of the high Alps, riding from Italy to Germany where IebeIlious rulers were making trouble. Or perhaps he would find that his presence was needed to settle disputes in Spain or Holland.

The wonder is that Charles V accomplished as much as he did. He was ambitious and energetic and a capable ruler. He had so many things to do that it was difficult to do any one of them well. Charles V surely must have known the true meaning of the saying, “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

Charles V secured temporary religious peace within Germany. After more than thirty years Charles did succeed in bringing an end to the fighting between the Catholics of his realm and rebellious German Protestants helped by the French. In 1555 he went to the German city of Augsburg to try to arrange peace between his Catholic and Protestant subjects. After a long argument, representatives of both sides agreed on the following points: (1) Any Catholic churchman who became a Lutheran Protestant must restore to the Catholic Church the Church lands he had ruled. (2) German free cities and towns and the rulers of German states could decide for themselves whether to be Catholic or Lutheran. (3) The people themselves everywhere in Germany must accept the religious belief chosen by their free city or town or by the ruler of the state in which they lived. Those who did not like the choice made by their government or ruler had to move to a place where their religious views were acceptable or run the risk of being persecuted.

This agreement, the so-called Peace of Augsburg, by no means provided full religious freedom, but it did bring about more than half a century of religious peace in Germany. Except for some small conflicts between Catholic and Lutheran states and their rulers, this peace lasted from 1555 to 1618.

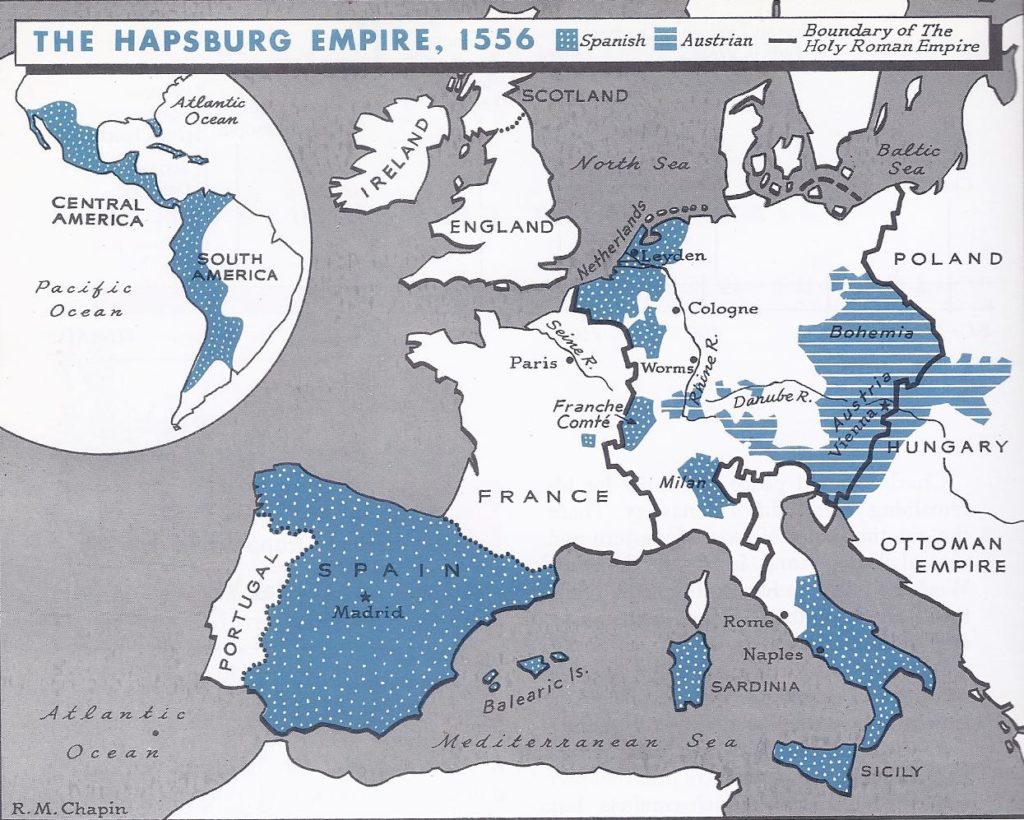

Charles divided his empire. In 1556, wearied by the burdens of ruling so vast and varied a realm, Charles V gave up his throne and divided his immense possessions between his brother Ferdinand and his son Philip. Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and ruled the Hapsburg lands in central Europe. Charles’ son Philip (the same King Philip II who later sent the Spanish Armada against the English) became the ruler of Spain, the Netherlands, parts of Italy, Sicily and Sardinia in the Mediterranean Sea, as well as the vast lands that Spain claimed in the New World.

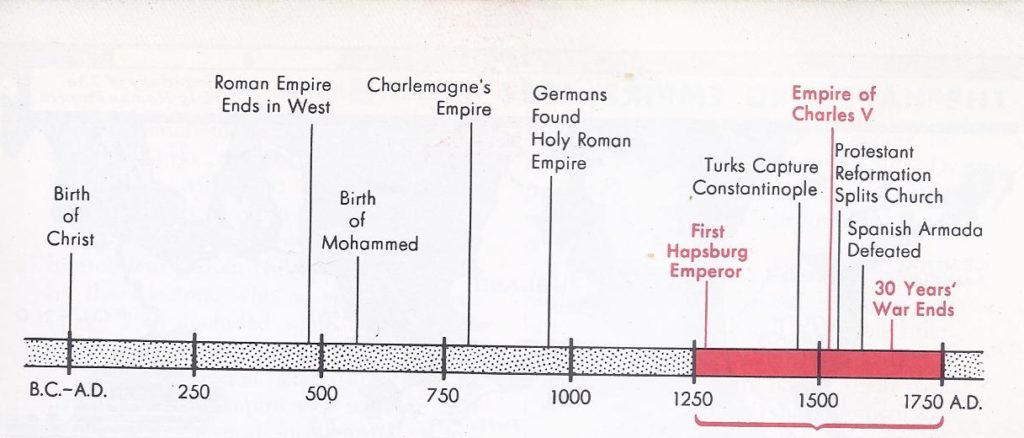

TIMETABLE – RISE OF THE HAPSBURG FAMILY

First counts of Hapsburg (a castle in Switzerland), 1000’s

Count Rudolph chosen Holy Roman Emperor, 1273

Rudolph made his sons dukes of Austria, 1283

Hapsburgs regularly chosen as Holy Roman Emperors, after 1438

A Hapsburg inherited the Netherlands, 1482

Charles V inherited Spain and the Spanish empire, 1516

As Emperor, Charles V united all Hapsburg lands under his rule, 1519

His brother Ferdinand became king of Bohemia and Hungary, 1526

Charles V divided the Hapsburg empire into a Spanish part ruled by his son Philip II and an Austrian part ruled by Ferdinand, 1556

The Hupsburg family ruled two separate empires. As a result of the division of Charles’ empire, two branches of the Hapsburg family ruled independently in Europe — the Spanish Hapsburgs in the West and the Austrian Hapsburgs in central Europe. The Spanish Hapsburgs ruled until 1700; the Austrian branch until 1918 and until 1806, when Napoleon’s victorious armies had overcome all opposition in central Europe, an Austrian Hapsburg almost always wore the crown of emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

The splitting of Charles’ unwieldy empire, however, did not free his successors from the kind of problems he had encountered. From within and without their realms the Austrian and Spanish Hapsburgs cnntinued to have trouble. Within, subject countries that were misgoverned rebelled. From without, rival rulers plotted and invaded in an age when “might meant right.” Differences between Catholics and Protestants played a part in many of these problems.

The Dutch Protestants rebelled against Philip of Spain. Religious differences played a part in the rebellion of the Netherlands against the Spanish Hapsburgs. Philip II of Spain was determined to be absolute master of his empire. He also believed firmly that the people of a country should accept the religion of the ruler. Among the people of the Netherlands, particularly in the Dutch or northern provinces, there were many Calvinists. Against them Philip turned his fury. Thousands, among them some high nobles, were put to death by Philip’s cruel general, the Duke of Alva.

In addition, Philip imposed heavy taxes and took away the rights and liberties of the prosperous towns. As a result, revolt swept the southern provinces (present-day Belgium) as well as the Dutch provinces. After a time, the southern provinces (which were Catholic) stopped fighting, on the promise that their ancient political rights would be restored, but the Dutch, aided at times by the French and English, continued the struggle.

William the Silent inspired the Dutch to achieve independence. The Dutch might well have been crushed except for the efforts of one man. This was William of Orange, commonly called “The Silent.” Actually, this nickname fitted William rather badly, for he was a good public speaker and knew several languages though he had learned to remain silent when surrounded by enemies and spies. The king of Spain put a price on William’s head and at last William was murdered by an assassin. In the years when he led the revolt against the Spaniards, William of Orange had taught his followers never to give up. The Dutch cut the dikes which held back the ocean and flooded large areas of their country to slow down the Spanish armies. Besieged cities such as Leyden held out even when their defenders were dying of hunger.

In 1581 the seven northern provinces boldly declared their independence. The struggle continued, however and it was not until 1648 that Holland was recognized as an independent nation. By that time Holland had become one of the great commercial powers of the world. Meanwhile, even more pressing problems had beset the Hapsburg rulers who succeeded Charles V in central Europe.

The Act of Abjuration

God did not create the people slaves to their prince, to obey his commands whether right or wrong, but rather the prince for the sake of the subjects . . . to govern them fairly. . . And when he oppresses them, seeking . . . to break down their ancient customs and privileges . . . then he is no longer a prince but a tyrant, and his subjects are to consider him in no other view. And particularly when this is done deliberately, unauthorized by the parliament, they may not only disallow his authority, but legally proceed to the choice of another prince. . . . This is what the law of nature dictates for the defense of liberty, which we ought to hand down to our children, even at the hazard of our lives. . . .

2. How Did the Thirty Years’ War Delay the Growth of Strong States in Central Europe?

In 1618 the uneasy peace between Catholics and Protestants within the Holy Roman Empire was shattered. The trouble began in Bohemia, the mountain-fringed plateau between Poland and the German states. Bohemia contained many Germans, but most of the people were Slavic in language and background The Bohemian people had a strong feeling of independence. For centuries Bohemia had been a separate kingdom within the Holy Roman Empire and elected its own king. In 1526 Ferdinand, the brother of Charles V, was elected to the throne. About 20 years later Bohemia was proclaimed a possession of the Austrian Hapsburgs, to be handed down from one relative to another.

The Bohemians had long been divided on religious matterst In the late 800’s missionaries had brought the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church to Bohemia. Then, a hundred years before Martin Luther’s time, John Huss, a Bohemian leader, had broken with the Church and had been burned alive for his defiance. Later the ideas of Luther and Calvin made headway in Bohemia The result was that some people in Bohemia were Roman Catholics, others Protestants.

The Thirty Years’ War began. Trouble arose when the Catholic Hapsburg ruler decided not to permit the growing number of Protestants in Bohemia to worship as they pleased. A group of Bohemian nobles showed their anger by hurling two of his representatives bodily from a palace window into a ditch seventy feet below. Somehow these two men survived the fall, but the insult enraged the monarch.

Then the rebellious Bohemians chose as their king a Protestant prince from a small German state. So the Catholic Hapsburg emperor sent an army into Bohemia which overcame the Lutheran “rebels.” Their defeat was important for two reasons. (1) Bohemia ceased to be an independent kingdom. Instead, it became more or less an Austrian province and remained so for about 300 years. (2) The Bohemian revolt marked the beginning of what is known as the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648).

Although the Thirty Years’ War began as a struggle between Catholics and Protestants within the Holy Roman Empire, it soon turned into a bitter contest for political power in central Europe. Nations on the Protestant side in this frightful and destructive war fought not only for religious reasons but to gain territory and to weaken the power of the Hapsburgs. Soon most of the nations of Europe were in the war.

Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden helped the German Protestants. The defeat of the Protestants in Bohemia frightened Protestants everywhere. The alarmed Germans looked northward for help to the Protestant Scandinavian countries. First to help the German Protestants was the king of Denmark, but the Danish troops were badly beaten. Then came the splendidly trained soldiers of Sweden under their remarkable king and general, Gustavus Adolphus. Leader of the Catholics was mighty Austria, the greatest of the German states, supported by Spain and other Catholic countries. On the Catholic side fought two very able generals, Tilly and Wallenstein. Soldiers from all nations flocked to their armies, some led on by religious zeal, many by the hope of plunder. Even Protestants enlisted in Wallenstein’s army of 50,000 veterans.

King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden turned out to be a military genius. The scornful Austrians had said, “This king of the snows will melt as he moves southward.” Instead, the victorious Swedish army marched from one end of Germany to the other. When the great Swedish king was killed in battle, Protestant hopes faded that Sweden would quickly end the war.

The German Protestants received aid from France. The Protestants in Germany, strangely enough, also received help from Catholic France. The chief minister of France was the far-sighted statesman Cardinal Richelieu. Richelieu had no love for the German Lutherans, but he disliked the Austrian Hapsburg rulers even more. He realized that the best way to weaken the Hapsburgs was to help the German Lutherans and their allies. So he lent money to Sweden and later he sent armies against Austria and Spain. At last all the states fighting in the Thirty Years’ War were so weary that they patched up a peace at Westphalia in Germany in 1648. This agreement ended the Thirty Years’ War.

The long war weakened the Holy Roman Empire. By the Peace of Westphalia, German rulers were permitted to introduce, Calvinist as well as Catholic or Lutheran forms of worship. As before, however, each German ruler determined what form of religion his subjects were to practice. In addition, Protestants were to keep Church lands which they had taken before 1624.

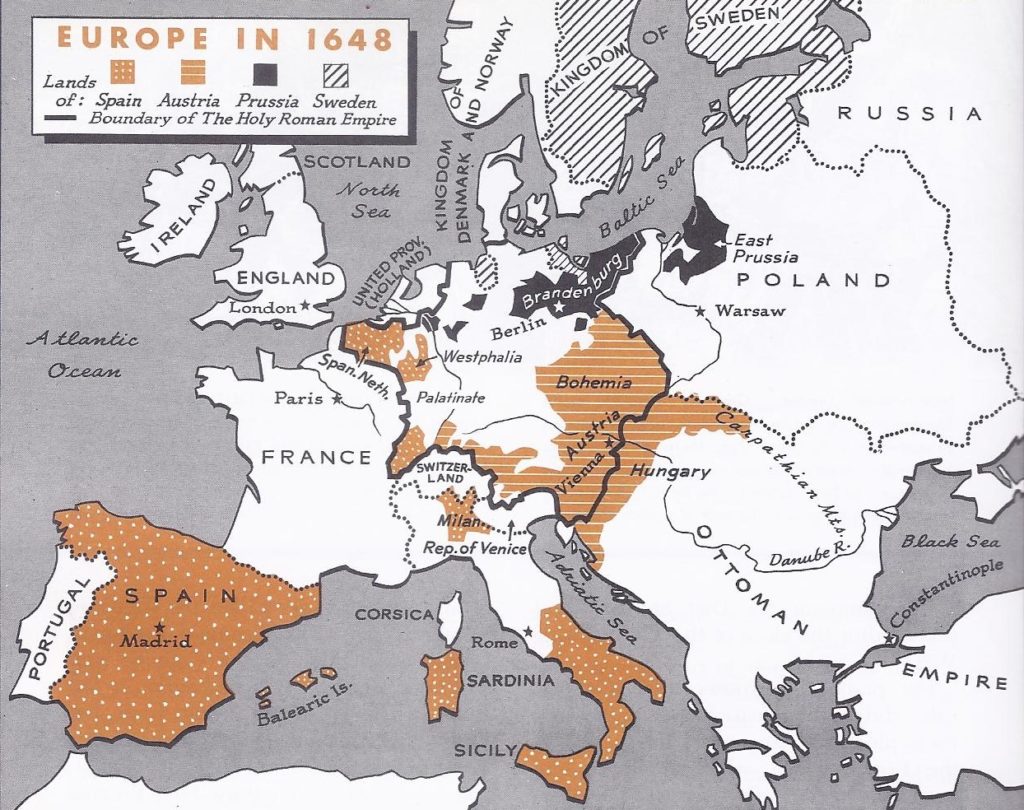

The Peace of Westphalia also brought important changes in the map of Europe. Switzerland and the United Provinces (Holland) were at last recognized as completely independent of the Holy Roman Empire. France was given some important cities on the border between Germany and France. Sweden gained valuable bits of land at the mouths of the German rivers running into the Baltic Sea. Some Lutheran states in Germany, such as Brandenburg-Prussia, became larger than before the war.

From now on, each state in the Holy Roman Empire was allowed to make peace, war and treaties on its own responsibility. The emperor’s position was more than ever a hollow honour. The dream of an empire closely united under the Austrian Hapshurgs and loyal to the Catholic Church was ended.

The war was a disaster to Germany. The Thirty Years’ War was one of the most destructive of modern wars. True, the armies were small compared with the huge military forces of our time, but the suffering among civilians, as in wars of our time, was frightful. During the course of the war a third or perhaps more of Germany’s population died. Many towns and villages were wiped out. Farms were burned, crops were destroyed, sheep and cattle were driven off or killed. “Then was there naught but beating and burning, plundering, torture, and murder,” reads an account of the destruction of a rich German city. Some towns and cities were plundered again and again. People rebuilt their homes only to have them destroyed. For every one who died fighting, famine and disease killed a score.

Evil effects of the war continued long after the fighting ended. Even the peace that followed the Thirty Years’ War did not bring an end to fighting in Germany. The French, under King Louis XIV, continued to fight the Austrians and the Spaniards; western Germany was one of the battlegrounds. Moreover, the German states were often at war with one another. There were over 300 such states. A few of them, like Austria and Brandenburg-Prussia, were large; others, much smaller and less powerful, were ruled by petty nobles. Still others were so-called free cities, little republics like the city-states of ancient and medieval times. There were also many lands ruled by highranking clergymen of the Catholic Church. Over all of them were the Holy Roman emperor and a lawmaking body called the Diet which was supposed to represent the many states. However, as we have just read, neither emperor nor Diet had any real power after the close of the Thirty Years’ War.

For practical purposes, each German ruler did as he pleased. What most of them pleased to do was to try to imitate the French kings, who maintained the most lavish court in Europe. The German rulers behaved as if they were ashamed of their language and their people. They levied heavy taxes in order to raise funds for the court life and the palaces they wanted. They squandered money on fancy uniforms and palace guards, gilded furniture, cut-glass chandeliers and court orchestras. Here the German nobility spent their time aping French ways. They wore Parisian clothes, danced French dances and made pretty French speeches to each other. Outside the palaces and the homes of the noblemen, German peasants toiled in the fields to pay the bills.

Prussia became powerful. Although Germany in general became weakened and disorganized as the result of the Thirty Years’ War, one German state greatly increased its strength. This was Brandenburg-Prussia. Nearly a hundred years before this war began, the leader of a crusading order called the Teutonic Knights became a Lutheran. Like many another former Catholic who had ruled Church lands, he held on to the lands when he broke away from the Catholic Church. The family name of this leader was Hohenzollern and he called his territory East Prussia. He had relatives of the same name who ruled Brandenburg, a German state which included the city of Berlin.

In 1618 Brandenburg and East Prussia were united under the same ruler. In large part, Brandenburg-Prussia owed its rapid growth in importance to Frederick William, who was called the Great Elector. Frederick William not only won victories on the Protestant side in the closing years of the Thirty Years’ War, but defeated the Swedes and Poles in later wars. This able general and statesman enlarged his territory and built it into a closely-knit monarchy.

The rulers who followed Elector Frederick William came to be called kings and their land became commonly known as Prussia. These Hohenzollerns were usually able men. They had one eye on filling the royal treasury and the other on building a strong army. King Frederick William I (1713-1740), for example, was a miser who spent money on little else but soldiers, particularly tall soldiers. He kept a regiment of “giants,” the Potsdam guards, just for the pleasure of watching them march with clock like precision. He took great pains to bring up his son to become a real king, as you may judge by the following instructions for his education:

. . . It is important that the boy’s character . . . should be . . . so formed that he will love . . . Virtue and feel horror . . . for vice. . . .

My son and all his attendants shall say their prayers on their knees both morning and evening, and after prayers shall read a chapter from the Bible.

He shall be kept away from operas, comedies and other worldly amusements. . . . He must be taught to pay proper respect and submission to his parents but without slavishness.

His tutors must use every means they can devise to restrain him from puffed up pride and insolence and to train him in good management, economy and modesty. Since nothing is so harmful as flattery, all those who are about . . . my son are forbidden to indulge in it on pain of my extreme displeasure. . . . His tutors shall see to it that he acquires a condensed and elegant style in writing French as well as German. Arithmetic, mathematics, artillery and agriculture he must be taught thoroughly, only a little ancient history, but the history of our own time and of the last 150 years as accurately as possible. He must have a thorough knowledge of law, of international law, of geography and of what is most remarkable in each country; and above all, my son must be carefully taught the history of his own family.

It was this son (known as Frederick the Great) who helped make Prussia one of the most powerful states in Europe and the chief rival of the Austrian Hapsburgs for the leadership of Germany. Austria and Prussia were exceptions. Germany as a whole remained divided and weak for centuries.

3. Why Did Certain Countries in Central and Eastern Europe Shrink or Disappear?

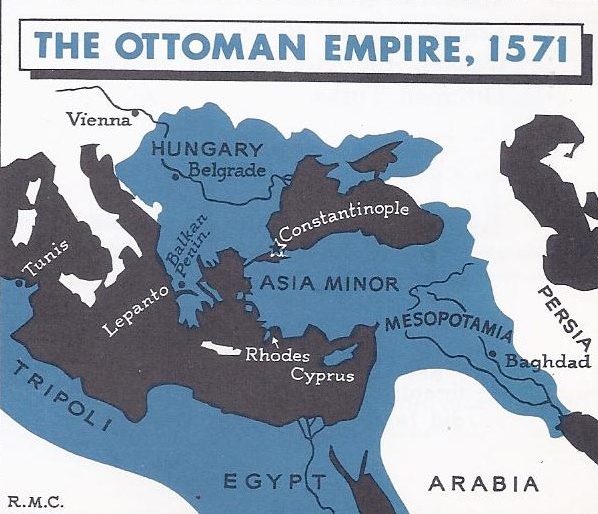

The story of the Hapsburgs would not be complete without reference to two other countries. To the east of Germany lay Poland, a region much larger than it is today. South of Poland, covering the Balkan Peninsula between the Adriatic and the Black Sea and extending into Asia and Africa, was the Ottoman Empire (Turkey). In the three centuries since the Treaty of Westphalia the changing fortunes of both Poland and Turkey provide an important chapter in Europe’s history.

Geography gave Poland little protection. In the 1500’s and 1600’s Poland was a large country. Most of it was a glat and open plain, with no natural boundaries except a short strip of coast line on the Baltic and the ridges of the Carpathian Mountains to the south. Poland included some parts of what is now Russia. Powerful states — Prussia, Russia, the Turkish Empire and Sweden surrounded it on all sides. Only Poland’s skillful statesmen, who knew how to play one enemy country against another and the superb Polish cavalry kept Poland free in the midst of the enemies surrounding it.

Polish nobles clung to their privileges. There were many different peoples and religious faiths in Poland, but most of the Poles were Roman Catholics. The government was sometimes called a kingdom and sometimes a republic, for although there was a king he was elected by the nobles for life instead of inheriting his crown from his father.

In Poland the nobles owned practically all the land. They were the only ones with the right to vote and hold office and they enjoyed many other privileges denied the common people. Most Polish people were peasants who toiled as serfs on the land owned by the nobles. There was almost no Polish middle class, most of the trade being carried on by foreigners.

Among the many political privileges belonging to the Polish nobles was one that did much to bring about the ruin of Poland. When the nobles voted on any question, all had to agree or the vote was not carried. In the Polish legislature or Diet, for example, a single vote cast against a proposed law would veto it. Even though such a system weakened the central government, the Polish nobles clung to their veto power as part of what they called their “golden liberty.” In fact, the Polish nobles guarded all their privileges jealously. They wanted no king with absolute power like the rulers of Prussia or Austria. Consequently Poland in the 1600’s and 1700’s was much like France in the days after Charlemagne — every nobleman a little king on his own estate, determined to be subject to no one.

Poland long remained an important state. In spite of a weak central government, Poland was for a time a nation of considerable strength. Polish cavalry prevented the barbarian hordes which invaded Russia and the Turks who invaded Hungary from sweeping farther into Europe. It was to Poland that the people of Vienna appealed for help when they were besieged by the Turks in 1683. Troops from the Holy Roman Empire took part in defending Vienna, but a Polish king, John Sobieski, led the victorious forces against the Turks. After the victory Sobieski wrote these words to his queen:

Praised be our Lord God forever for granting our nation such victory and such glory. . . . The whole camp of the enemy, with their artillery and untold treasure, has fallen into our hands. . . . The grand vizier [leader of the Turkish army] lost all his rich treasure and barely escaped on horseback, with nothing but the coat on his back. . . . This morning early I went into the town [Vienna] and found that it could not have held out five days longer. Never have the eyes of men beheld so great damage done in so brief a time; great masses of stone and rock have been broken up and tossed in heaps . . . and the imperial castle is riddled with holes and ruined by their cannon halls. . . . Crowds of people . . . tried to kiss my hands. . . . Together they lifted up a shout of joy. . . .

Later, Poland was divided up by Austria, Russia and Prussia. In the long run, neither the triumph over the Turks at Vienna nor other important military victories could keep Poland independent. During the late 1700’s the rulers of Poland’s powerful neighbours Russia, Prussia and Austria — divided Poland among themselves. The selfishness of the nobles, who refused to see the need for unity in the face of ever-growing danger from outside enemies, had cost Poland its life as a nation.

The Ottoman Turks came out of Asia. The Hapsburgs benefited by the weakness of Poland but faced a serious threat, as did all western Europe, from the Moslem Turks. In the 1200’s large numbers of nomadic (wandering) plainsmen from the prairies of central Asia swept westward toward Europe. Among these soldier-herdsmen were the Ottoman Turks. From their old homes east of the Caspian Sea the Turks rode into Asia Minor, seizing the border fortresses and cities of the Eastern Roman Empire. At last only the narrow strait of the Bosporus lay between the victorious Turks and the great city of Constantinople.

The Ottoman Turks conquered Constantinople. Eagerly the Turks eyed the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire but because Constantinople’s defenses were strong, the Turks found it easier to conquer the surrounding country. During the 1300’s, therefore, they gradually gained control over much of southeastern Europe. Then when Constantinople had become weak and its population had shrunk, the Turks struck at the ancient city. The rulers of Europe were too busy fighting one another to unite in the city’s defense. In 1453, after a long siege, Turkish troops finally fought their way into Constantinople. There was now nothing left of the old Roman Empire. Some of the Christian churches in Constantinople became Moslem mosques where Turks prayed to Allah and Turkish sultans moved into the palaces in which Roman emperors had lived. To this day Constantinople (Istanbul) is a Turkish city.

Ottoman power threatened Europe. From Constantinople a succession of sultans ruled the Turkish empire. This included land in Europe, Asia and parts of North Africa. From Constantinople the Sultans also sent orders for the Turkish armies to press farther into Europe. They not only completed the conquest of the Balkan Peninsula but spread into southwestern Russia, overran Hungary and threatened Poland and Bohemia. Their navies plowed the Mediterranean Sea.

Constantly during the 1500’s and 1600’s, the Austrian and Spanish Hapsburgs found their territories and power challenged by the Turks. Twice the Turks battered at the walls of Vienna, the capital city of the Austrian Hapsburgs. Matters were made worse for the countries so attacked by the fact that French kings, traditional enemies of the Hapsburgs, sometimes allied themselves with the Turks. The old crusading spirit that, centuries before, had united the Christians of Europe against the Moslems was gone.

The Turks borrowed their civilization. The ancestors of the Turks who conquered Constantinople had been hardy horsemen and shepherds without a highly developed civilization. As they conquered lands controlled by the Arabs, who had preserved and carried forward the earlier civilization of the Greeks, the Turks adopted new ways of doing things. For example, they learned how to use Arabic letters to write in Turkish. What is more important, the Turks adopted the religion of Islam.

In the lands which the Turks conquered they did not try to stamp out Christianity, although they taxed Christians heavily and at times treated them harshly. European merchants and traders, though taxed for the privilege, were allowed to buy and sell goods in Turkish territory. These were indeed rich markets. A look at the map will show that the Ottoman Empire, as the empire of the Turks came to be called, stood squarely across the trade routes between Europe and Asia.

Turkish power declined. In time, the pressure of the Turks in eastern and southern Europe diminished. Less able sultans, who preferred pleasure to power, handed over control of governmental affairs to favourites. Taxes went higher and higher and corruption spread in government circles. Turkish troops began to play politics, making the man who promised them the most favours their sultan. He would rule until another leader could promise the soldiers even more. To the east, the Persians made attacks which cost the Turks dearly in men and resources. Turkish power began to decline after a fleet of Spanish and Venetian galleys won a great naval victory off Lepanto in Greece in 1571.

Though conflicts on land and sea continued, by the year 1700 the Turkish advances in Europe had come to an end. Turkey gradually lost territory that it had once ruled both in southeastern Europe and in northern Africa. Just as corruption within and attack from without brought about the gradual decay of the old Roman Empire, so did these two forces help to weaken the empire and power of the Ottoman Turks.

4. How Did People in Western and Central Europe live in the Mid-1600’s?

The history of Europe in the 1600’s, let us remember, was more than the story of ambitions of rulers and the rise and fall of states. What about the people themselves? How did they carry on their daily lives amid the shifting of power and the destruction and suffering caused by wars? In section we find answers to these questions.

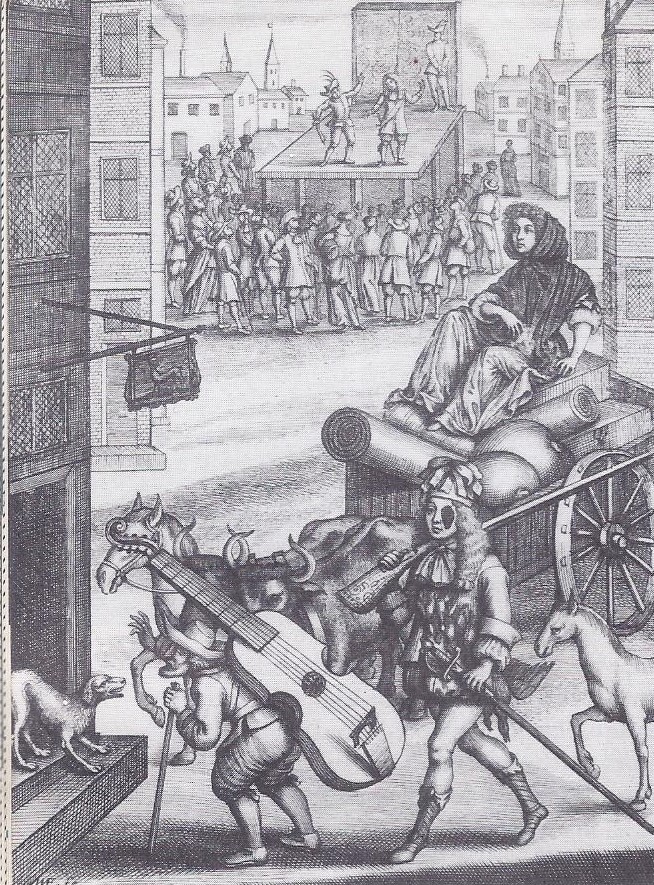

Town life had not changed greatly in two or three centuries. If Pierre, the imaginary serf mentioned, had revisited the equally imaginary city of Lacourt 300 years later, what would he have found? Had he arrived on a Saint’s day, this runaway farm lad doubtless would have been bewildered. The streets near the heart of the city would be choked with wagons and carts, their drivers shouting at one another or at the people who blocked the way. Peddlers would be ringing their bells and advertising their wares in singsong voices. Possibly there would be a parade. Yelling children, barking dogs and bellowing cattle would add to the din.

After Pierre became accustomed to the sights and sounds of the city, he would notice certain changes. The construction of the cathedral, for example, might be completed. There might be more stone buildings and the cobbled streets might be cleaner and drier. Pierre would have been sure to notice that the city had spread out. The tall walls that for hundreds of years had protected the old town had been destroyed by cannon balls during a siege. Now that the townspeople of Lacourt could count on the king’s soldiers and cannon for protection, they had built a new town beyond where the walls had stood. The farther from the heart of the old city, the cheaper the land, so many a shrewd craftsman bought land outside and built his home and workshop there. The growing towns and cities of the 1600’s showed no marked change in ways of living nor any real improvement in public health. Disease caused by dirt and ignorance spread quickly and epidemics were common.

Manufacturing and commerce grew in the 1600’s. Although outwardly city life in the mid-1600’s seemed little different from what it had been in the late 1300’s and the early 1400’s, slow changes were taking place. This was especially true in the production and exchange of goods. Merchants and other members of the middle class were becoming more prominent in city affairs, while the nobles were slowly losing their power and influence. At the same time, the once powerful craft guilds were becoming less important.

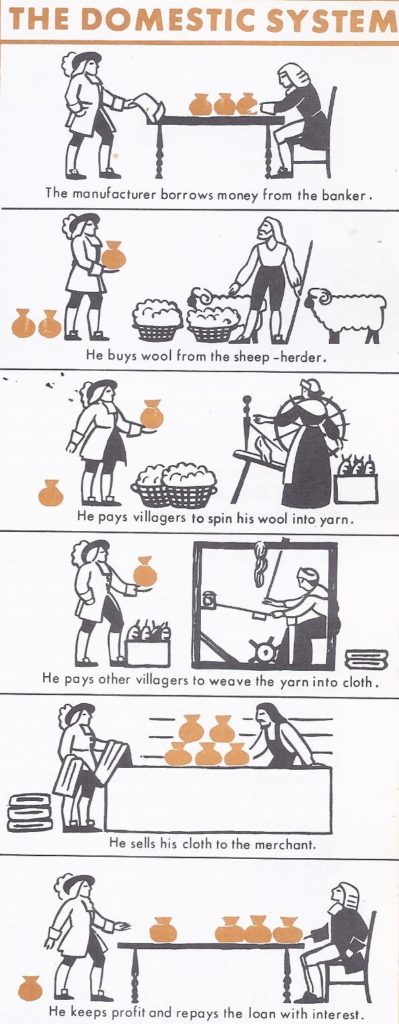

In place of the guilds a newer system of manufacturing was coming in. A man would go to a banker and borrow cash to buy raw wool from the sheepowners. The wool buyer would then find people who would spin the raw wool into yarn in their own homes. In addition, the wool buyers would find weavers who would take the yarn home and weave it into cloth on their own looms.

Instead of working for a weekly wage, these spinners and weavers were paid for the amount of yarn they spun or cloth they wove. Due to big profits to be made by this system of cloth manufacturing, the method spread widely. It is called the domestic system, because the actual spinning and weaving was done in the homes of the workers. While factories or mills were few, there were many small workshops where tailors, clockmakers and other craftsmen worked.

New products appeared in European markets. The rich resources of the American continents as well as of India, the Spice Islands and China were now open to traders and wide-awake Europeans turned to importing products from these faraway lands. As a result, trade flourished and merchants and bankers prospered. This overseas trade introduced entirely new products to Europeans and greatly increased the supply of hitherto scarce articles. Products from other lands meant greater comfort and influenced social customs. For example, as coffee came into wider use, coffeehouses became popular gathering places where men talked politics, gossiped and smoked. It should be remembered that the new luxuries were for only the well-to-do. The vast majority of city dwellers lived in poverty.

European peasants lived a hard life. Life in the country had changed even less than town life. Except for occasional windmills or water mills, European peasants made no use of mechanical power. Almost all farm work was still done by human labour, oxen and horses. Many peasants plowed with wooden plows; a lucky few had plows with iron tips. No farms 800 years ago had tractors, reapers, binders or other machines such as are common on farms today. Some peasants fared better than others, for an increasing number were beginning to own their own farms. Nevertheless, for most farmers, tilling the soil continued to be an endless round of dull and back breaking labour. They had to work hard to raise enough food for themselves and judged by today’s standards their meals were monotonous. Cattle were thin and scrawny, for scientific breeding and feeding of livestock had scarcely begun.

Life, of course, was not all toil. There were country dances with their set steps and patterns and such old games as blindman’s buff. Just for the men, of course, there was wrestling, outdoor bowling and archery. Always there was talk about crops, livestock and the taxes that grew heavier every year. On Sundays old and young, men and women, went to church.

Dutch merchants and bankers of the 1600’s met at the Amsterdam bourse, or stock exchange, to carry on business. Amsterdam at this time was one of Europe’s busiest commercial cities.

European peasants dressed differently from city people. The farmers of western Europe wore trousers, jackets, and vests of cloth or leather. Wooden shoes were common, but well-to-do peasants wore leather shoes to church on Sundays. The women on the farms, finding that they could not keep pace with changing fashions in dress of the faraway city, solved their problem by making dresses intended to last indefinitely. No doubt you have seen pictures of these colorful old-fashioned garments. Such dresses were worn on Sundays and on other special occasions. Generally, older women tended to wear dark, quiet colours. Bright, gay colours were meant for young women and girls.

Life in the 1600’s lacked many present day “necessities.” Nowadays you look for a match if you want to light a fire, but in the 1600’s flint and steel were used instead of matches. Houses were lighted at night with candles or smoky oil lamps. A pen to write with was made by slicing the quill of a feather. You paid for a letter when you got it instead of when you sent it — and you were lucky to get a letter intended for you, so irregular and inefficient were the postal systems.

If your tooth ached, you could find a dentist who would pull it, but you would have to bear the pain. Anesthetics were not discovered until a little more than a hundred years ago. Even if an arm or leg had to be cut off, the only way then known to dull the pain was to make the patient drunk.

Gallstones removed from slain animals were highly regarded as protection against poison. A piece of horn from a mythical animal called a unicorn (actually a chip of ivory) was supposed to be useful not only for detecting poison but also for curing disease. Another “remedy” was a strand from the rope that had been used to hang a condemned criminal. Hangmen made good profits by selling such bits of rope. “Weapon ointment,” used to cure wounds, worked fairly well as a cure because the wounds were cleanly bandaged and let alone, but the ointment was smeared on the weapon instead of the patient! Despite these superstitions, there were a few doctors who were ahead of their times. Nevertheless medical science had far to go in the mid 1600’s.

People were divided into social classes. In most countries the law recognized three classes: the clergy, the nobility and the common people. Actually, however, the division into three classes was not as rigid as in earlier times. In England, for instance, there were only a few hundred titled nobles, but the class of so-called “gentlemen” was much larger. What made them gentlemen was not the law or descent from a long line of famous ancestors, but wealth — especially the ownership of land and having the education, dress, speech and habits that marked their class.

An English businessman, be he ever so rich, was not counted “gentle”– but there were ways to break into that class. The first step was for him to sell his business, buy a country estate and learn to hunt foxes. Next he should send his sons to such exclusive schools as Eton or Harrow and then to Oxford or Cambridge for university training. Then the ex-businessman should try to have his sons marry the daughters of country gentlemen. These sons would be counted gentlemen. His grandsons, with luck, might become knights or even nobles.

In France, the noble class was large. It included almost all who would be considered gentlemen or who lived by the rents from their lands. Between 1600 and 1750 very many wealthy persons became nobles. Some nobles, however, were poor.

Distinctions existed also wilhin a class. Even among the common people there were different social ranks. In France a wealthy merchant, though it was harder for him to rise into the class of gentlemen than in England, stood far above a craftsman, a peasant, or a labourer.

The peasants themselves were not all on the same level. A freeman owning his own farm, like the free farmers of England or the more prosperous peasants in Sweden, Germany and France, worked with his hands. so he occupied a lower position than a landlord who merely managed an estate or collected rents. The independent farmer stood above the tenant farmer, who had to rent his farm from a landlord. The tenant farmer, in turn, stood above the agricultural labourer or hired man, who had no land at all and merely worked for wages. Finally, all freemen stood higher than serfs. Serfdom had died out in Great Britain and was declining in France, Scandinavia and most of western Europe. Nevertheless it was still the rule in eastern Germany, Hungary, Poland and Russia.

The classes were kept apart by law and by custom. Distinctions between different classes were very real. In some countries it was against the law and in all countries contrary to custom, for a commoner or common person to dress in the fine clothes of a gentleman. Nor was the commoner supposed to wear his hair down to his shoulders in the manner of a gentleman or to carry the gentleman’s light sword, or rapier.

There were many other restrictions that kept different classes of people from mixing. To marry outside one’s class, for example, was not supposed to happen but sometimes did, especially when poor noblemen found it advantageous to have their daughters marry rich merchants. In Prussia, for example, even the land itself was divided into classes according to the class of the owners, such as nobles’ land and peasants’ land. Without special permission from the king, no one could buy land from a member of another social class. Furthermore, appointments as officers in the Prussian army were limited to gentlemen.

Belief in human equality was rare. You can see that in the mid-1600’s there was no such thing as democracy in government, in ways of earning a living, or in social life. Only in a few countries, such as England, Holland and Switzerland, was there progress toward guarding the rights of the people. In most countries at this time the idea of freedom and equality among men was practically unknown. Anyone suggesting such an idea would have been regarded as a crack pot. A hundred or more years were to pass before men in a new land across the Atlantic were to declare, in a document accepted by an entire people, that “all men are created equal” and that they have such rights as “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”