Christianity was the movement that spread Across the Roman Empire Pointing the way for the rest of the ancient world toward belief in a single God.

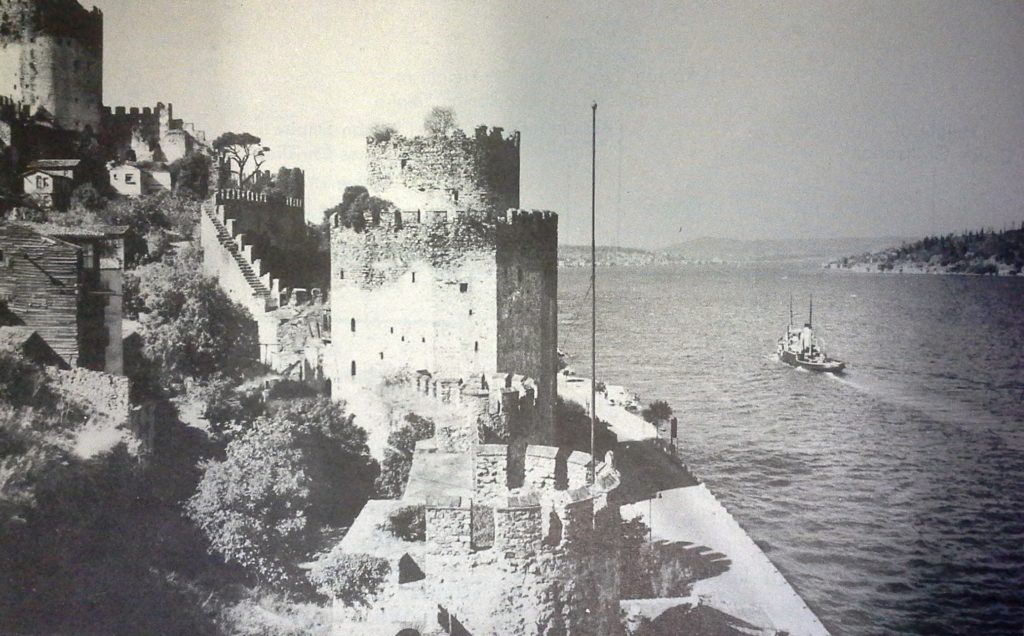

The year is 400 A.D. Andropolos paces impatiently up and down the deck of the merchant ship. He is eager to get back home; and to Andropolos, home is the city of Constantinople, a new capital of the Roman Empire. He can already see the walls and buildings of the great city shimmering in the distance. Now the ship is nearing the narrow Bosporus, the waterway where Europe and Asia are hardly a mile apart.

The voyage from Ostia, the port of the old city of Rome, had been long and tiresome. Andropolos had been only too glad to leave Italy. The city that was once a hub of the Roman Empire, though still large, had a down at the heel look. Simultaneously the cities of northern Italy were becoming crowded with rough barbarians. Tall Germans also were filling the ranks of Roman legions. In times past, men such as these had been defeated again and again by Roman armies made up of men from Italy, but those victories had been won long ago and Rome had no such fighters left.

Yes, Andropolos is thankful to leave Italy. Here in Constantinople the authority of the Roman emperor still counts. Andropolos shakes his head sadly as he recalls what has happened — the Roman Empire is not what it used to be. For Andropolos, though he is Greek born and Greek speaking, proudly calls himself a Roman citizen.

The walls of Constantinople on the left grow closer as the ship enters the Bosporus. Soon it will dock in the harbour of the Golden Horn and Andropolos’ long voyage will be over. When he steps ashore, the first thing he will do, good Christian that he is, will be to go to the nearest of the many churches in Constantinople. There Andropolos will kneel and thank the saints for his safe trip home.

Such a story as this points to the startling changes that had taken place in the Roman Empire. Once proud cities of Italy overrun with rough German warriors? Constantinople a capital of the Roman Empire and the emperor’s home? Christian churches in Constantinople? How these things happened will be described under these headings:

1. How did the Roman Empire decline in the West but survive in the East?

2. How did Christianity spread in the Roman Empire?

3. What did the Byzantine Empire contribute to civilization?

1. How Did the Roman Empire Decline in the West but Survive in the East?

As you may have gathered from the story of Andropolos, conditions in Italy were far different three or four hundred years after the time of Christ from what they were during the days of the early emperors. These changes took place over a long period of time. The western part of the Roman Empire died slowly, like a huge grizzly bear weakened by sickness and by wounds made by wolves slashing at his sides. What were the “sicknesses” that weakened the Empire in the West? Who were the “wolves” that attacked the Empire from without?

The Empire suffered from the confusion of many emperors. After about 200 A.D.,, the Roman Empire suffered from many kinds of inward weakness. One important cause of trouble was the method of choosing emperors. The Roman armies now claimed this right for themselves and ambitious generals sought the support of the soldiers who could make them rulers of Rome. These generals and their soldiers fought others who sought to become emperor. The resulting warfare and violence brought hardship to the people and created much confusion. The peace that Romans had enjoyed during the reigns of the earlier and stronger emperors broke down. Twenty-five emperors ruled from 235 to 284 A.D., an average of not quite two years’ rule per emperor and of these 25 emperors, most were murdered!

Conditions improved temporarily under two emperors. Two strong rulers — Diocletian and Constantine — ended these army-led revolts and civil wars. They also reorganized the government and made it much stronger. Under their rule all power stemmed from the emperor, whose orders were carried out by ever growing numbers of government officials. The emperor also held firm control over the army.

To carry on the government more efficiently, Diocletian appointed a co-emperor in the West while he made his head quarters in Asia Minor. Constantine took the further step of founding a new capital at Byzantium, an old Greek city on the Bosporus at the entrance to the Black Sea. Thus Byzantium, which the Emperor renamed Constantinople, became a new Rome, the headquarters of the Roman Empire. For a time Constantine ruled the entire empire, but after his death it became the practice to have two emperors at the same time, one in the East and another in the West.

The steps taken by Diocletian and Constantine between 284 and 337 A.D. restored order to the Empire for the time being, but their strong, direct rule also put an end to what little self-government was left in the cities of the Empire. Strong central government was also costly, as was constant warfare against invaders. As a result, although high officials and a small number of very rich people lived in luxury, most people were burdened by higher and higher taxes.

Other conditions weakened the Roman Empire from within. Although few people at the time seemed to realize it, the Empire, especially in the West, was growing weaker. Due to fewer births and widespread epidemics, population was declining. Fewer workers meant less farm produce and fewer manufactured articles. Efforts to step up production by “freezing” farm and shop workers in their jobs and forcing young people to follow their fathers’ occupations did not help. In fact, many workers resented these restrictions. They felt that the Empire was a hard taskmaster which deprived them of their freedom.

These conditions brought still further weaknesses. Rome’s power and glory had been built up in large part because of the personal qualities of its people, their fearlessness, strong purpose and devotion to duty. Romans in the later Empire lacked these qualities. The wealthy had grown soft through easy living, while the great mass of people had lost hope of improving their condition. Their attitude was to accept life as they found it rather than to struggle to improve it. Even so, the Roman Empire in the West might have continued for a much longer time except for the pressure of peoples from outside.

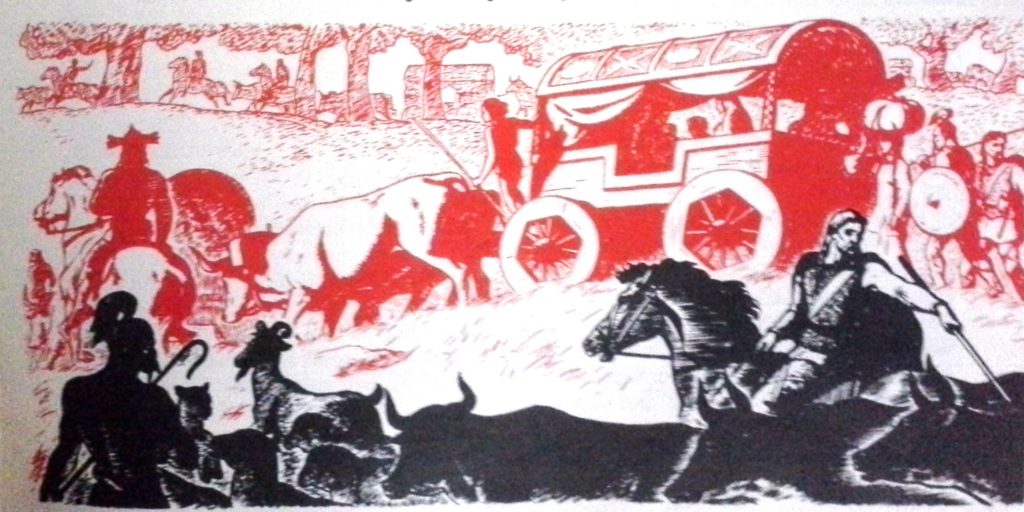

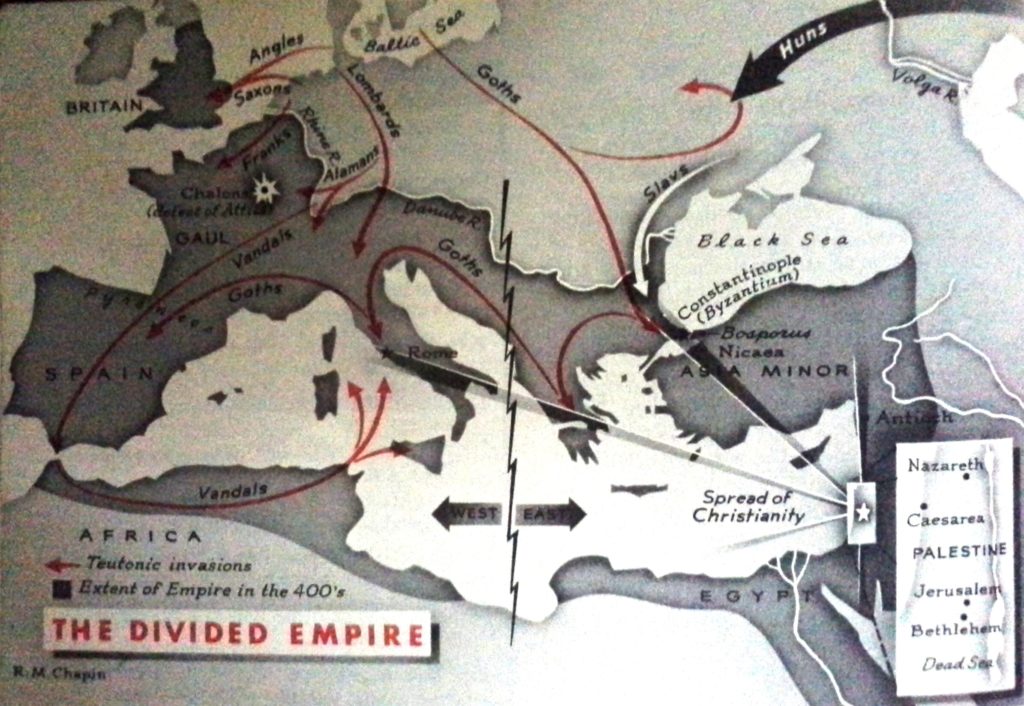

Barbarians (the word barbarian, applied by the Greeks to outsiders or foreigners, came to mean “uncivilized” or “half civilized”.) entered the Empire in growing numbers. Movements of whole masses of people had frequently affected the history of countries and changed the political map of the world. Between 200 and 500 A.D., important migrations occurred in Europe. Driven by overpopulation and changes in climate, tribes from what is now Scandinavia and the lands bordering the Baltic Sea wandered southward into central and southern Europe. At the same time, tribes from Asia migrated westward into central Europe. These newcomers pushed ahead of the other tribesmen who had been living in central Europe for centuries.

These uprooted barbarian tribesmen eventually reached the northern boundaries of the Roman Empire — the Rhine and Danube Rivers. Sometimes they broke into the Empire. At first the Romans pushed them back, but as the Roman population declined it became difficult to recruit soldiers. These barbarian tribesmen were fierce warriors and therefore the Roman government hired them by the thousands to fill the thinning ranks of the Roman army. Other barbarians were allowed to settle within the Empire and till the soil.

These barbarian tribesmen were Teutons. The invading tribes were known by many names — Goths, Lombards, Franks, Alamans, Vandals and others — but all spoke languages more or less alike. These languages belonged to the Teutonic branch of the Indo-European speech group and the tribes are called Teutonic and the tribesmen are known as Teutons. The Vikings or Norse men of later years, for example, were Teutons. So were the tribes dwelling in what is now Germany. The Roman historian Tacitus has left us an interesting account of the Teutons of ancient Germany. He told of their strength, courage, and loyalty at a time when the Romans were becoming weak and soft. He also wrote about their less pleasant traits. The following condensed account is based on the words of Tacitus.

The Germans have no cities but live in separate dwellings far apart. They use crude building materials. They also have caves, dug by their own labour, where they find shelter from the cold and hide their food from invaders. . . . Men and women alike dress in loose robes or in animal skins. . . Marriage is considered sacred. At the marriage ceremony husband and wife exchange gifts of arms and cattle. Husband and wife remain partners until one of them dies. . . Children grow up to be strong, but live in great filth. They are as fond of their uncles and aunts as they are of their own parents. . . . Sons inherit their fathers‘ property. . . . If one man kills another, he pays the family of the victim a suitable number of cattle, which avoids feuds. . . . There is free hospitality. Hosts and guests eat and drink to excess; often their love of strong drink destroys them. . . . The men are great gamblers with dice and think nothing of gambling away their freedom. . . . Slaves, who are not numerous are for the most part weII treated. . . There are no permanent farms. The land, which is abundant, is divided among the families from year to year. . . .

New invaders, the Huns, drove Teutonic tribes across Roman borders. After 350 A.D. large numbers of Teutons sought to enter the Roman Empire. They were set in motion when a savage people called the Huns left their homes on the wide plains of Asia and poured into Europe. Fierce though the Teutons were, the Huns were even more savage. These mounted warriors could cover great distances in a day, leaving a path of death and destruction behind them. As the Hunnish horse men swept into Europe, the Teutons fled before them in terror. Whole tribes of Teutons sought safety within the boundaries of the Roman Empire and the emperors, needing soldiers badly, let them stay.

The city of Rome was captured by the Visigoths. More and more Teutons joined the Roman armies and some of them became high ranking officers. Sometimes entire Teutonic tribes fought for the Romans under their own Chieftains; sometimes these so called allies fought against the Romans. At last, the time came when the Teutons were too strong for the Romans to control. A tribe called the Visigoths, which had settled south of the Danube, rebelled against the emperor and wiped out his forces in battle. Later on, these same Visigoths moved into Italy. In 410 A.D. under their chief, Alaric, the Visigoths captured and plundered Rome, the city that had stood unconquered for 800 years.

The western part of the Empire finally fell prey to invaders. For years the Huns continued to ravage central Europe and kept the Teutons on the move. The ablest Hun ruler, Attila, controlled a vast empire which stretched from the upper Danube to the borders of Asia. The savage Attila, who called himself “the scourge of God,” forced the Roman emperors to pay him tribute. He also set out to seize the western part of the Empire but was checked in the battle of Chalons, in what is now France, in 451 A.D. After Attila’s death, the Hun empire broke up and these savage people retreated eastward.

Meanwhile, more Teutonic tribes pushed into Roman territory. They came down from the Alps into Italy; across the Rhine and into Gaul, over the Pyrenees into Spain; into Africa by way of Spain; into Britain — an endless, savage flood. The end of Roman rule in the West came in 476 A.D., when the barbarian commander of the Roman forces in Italy seized control from the emperor. Thereafter, Teutonic chiefs or kings ruled in western Europe.

Under the Teutons, civilization declined in the West. The Teutonic conquerors of the West were still barbarians. It is true that they raised crops of grain and kept herds of cattle, horse, sheep and pigs. They were also good metalworkers, but first and foremost the Teutons were warriors. Few of them could read or write. They had little knowledge of city life and were unskilled in the arts and crafts of the Romans.

In some areas, such as present-day England and northern France, the Teutons killed off or drove out the Romanized population. Elsewhere, as in Italy, southern France, Spain and North Africa, Teutons took over the government from the Roman rulers. The people who lived in these former parts of the Roman Empire were disarmed and became the subjects of the barbarian Teutonic rulers.

The triumph of the Teutons started a long decline in civilization in western Europe. Teutons spoke different languages than the Romans and had different laws and customs which interfered with the Roman way of doing things. Moreover, centuries of war during the Teutonic invasions had spread destruction and poverty throughout western Europe. Commerce and industry slowed down. Education and learning also declined.

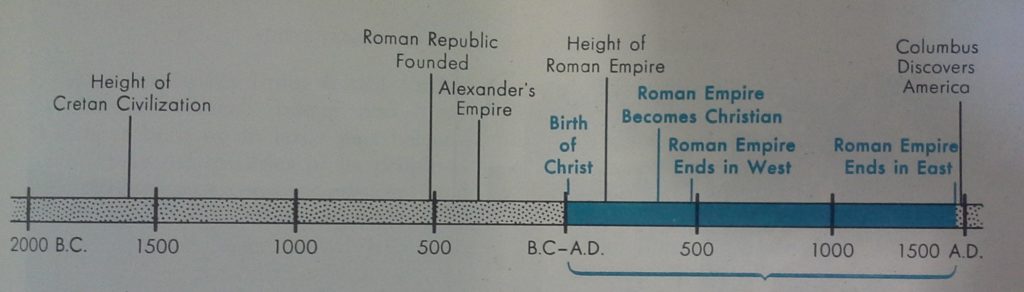

The Roman Empire survived in the East. After Constantine there were usually two or more emperors in power at the same time. These emperors resided in different parts of the empire. Finally in 395 A.D. the Roman world was divided into two separate parts, the Roman Empire of the West and the Roman Empire of the East. It was the Empire of the West that the Teutons had overrun.

THE ROMAN EMPIRE TIMETABLE

Augustus ruled as first Roman emperor, 30 B.C. to 14 A.D.

Rome gave two centuries of peace to the Mediterranean world.

Empire reached its greatest extent, 117 AD.

Period of army mutinies and civil war, 235 to 284 A.D.

Diocletian and Constantine restored order, 234 – 337 A.D.

Christians obtained religious freedom, 313 A.D.

Constantine made Constantinople the capital of the Empire, 330 AD.

Division of the Empire into an eastern and a western half, 395 AD.

Barbarians deposed the Roman Emperor in the West, 476 A.D.

The Eastern Empire enjoyed its greatest power under Justinian, 527 – 565 AD.

Enemies who attacked the Roman Empire of the East were not as successful as were the Teutons in the West. For at least four reasons, the Roman emperors managed to hold on to a large portion of their eastern territory. (1) There had been no great decline in population in the East as there had been in the West. (2) The emperors in the East proved abler and stronger than those in the West. (3) The East was richer. So Rome’s rulers there bought off many barbarian attackers, even bribing some tribes to attack the West instead of the East. (4) The emperors were able to recruit soldiers from warlike peoples in Asia Minor. With these troops the emperors could control Teutonic warriors who made trouble.

About 550 A.D., an emperor in the East tried to win back the lost western portion of the Empire. He was Justinian, the emperor who had Rome’s many laws collected in a single Code. Justinian succeeded in winning back North Africa, Italy and the nearby islands, but he lacked funds to regain all the West.

The Eastern Roman Empire had enemies of its own. Although the Eastern Empire was more fortunate than the Western, it too was plagued by invaders after justinian’s death. People called Slavs, from what is now southern Russia, settled in the area south of the Danube. On the far eastern borders of the Eastern Empire the Persians struck hard. The emperors fought back and barely managed to hold their own. Then, exhausted by long continued warfare, the Empire lost Syria, Palestine and Egypt to new enemies, the Moslems. The Moslems were warlike followers of a great religious leader, Mohammed.

The Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire lived on. The map shows what was left of the Roman Empire in the East by 750 A.D. This Byzantine Empire — as it came to be called after Byzantium, the ancient name for Constantinople — lived on for many centuries. It remained the one highly civilized state in this part of the world and the chief defender and preserver of Greek and Roman civilization.

2. How Did Christianity Spread in the Roman Empire?

The Israelites were intensely religious and they pointed the way for the rest of the ancient world toward belief in a single God. During the days of the early Roman emperors, there arose in the province of Palestine another religious movement that was to sweep across the Roman Empire and eventually around the world. That movement was Christianity.

Christianity grew from humble beginnings. Jesus, the founder of the Christian religion, was born during the reign of Augustus in Bethlehem, a small village near the city of Jerusalem in Palestine. He grew up in the Village of Nazareth. Then, for a few brief years, Jesus moved among the people, aiding the sick, the unfortunate and teaching a religion of love, of God and of one’s fellow men. He gave people hope of a future life. Among the common people of Palestine, the religious teachings of Jesus drew ever growing numbers of followers. To them, Jesus was the Messiah, or Saviour, whose coming had long been promised by the Jewish prophets.

However, some people in Palestine regarded Jesus as a religious troublemaker, while others were disappointed that he would not lead a revolt against the Romans. So enemies of Jesus turned him over to Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor of Palestine. Pilate, who perhaps thought religious unrest might lead to political disturbances, permitted Jesus to be put to death. The method used was the cruel one of crucifixion, common in those days for executing criminals. Christians ever since have used the cross, the crucifix, as the symbol of their faith.

Christianity spread in the Roman Empire. The closest followers of Jesus, called disciples or apostles, spread the Gospel or “Good News” their crucified master had taught them. In fact, the disciples and the people they converted carried Jesus’ teachings all over the Roman Empire. Some of them went from city to city over the marvelous Roman roads. Others traveled by sea. It was in Antioch, a city in Syria, that the followers of Jesus were first called Christians (The name Christian comes from the Greek word Christos, or Messiah.) Among the early Christian missionaries was the apostle Paul, who organized Christian groups in Asia Minor and Greece and later went on to Rome itself. Another was Peter, one of the original band of twelve disciples, who became the leader of Rome’s first Christians.

The spread of Christianity alarmed the Roman government. At first government officials ignored the Christians. Before long, however, the Roman authorities came to regard them as followers of a dangerous new faith. These people believed in only one God and refused to worship the official gods of Rome. This fact prevented them from taking part in such activities as holding office or serving in the army. Moreover, the Christians would not admit that the Roman emperors were divine, as all subjects of Rome were expected to do. The early Christian belief that a Kingdom of Heaven on earth would soon be established and seemed to threaten the Roman Empire itself. To government officials in the Empire, therefore, the early Christians appeared to be a dangerous, disloyal group that should be punished and suppressed.

Christians were persecuted. The early Christians were persecuted but not wiped out. In 64 A.D. a disastrous fire destroyed a large part of Rome and the Christians were blamed for it. Nero, one of the worst of all Roman emperors, ordered the arrest and execution of the Christians in the city. Some were burned alive; some were Crucified; others were torn to pieces by wild dogs and lions in the arena of the capital city as Romans watched the bloody show, but the Christians would not give up their religion. They continued to gather and worship secretly in the catacombs, the long, dark, winding under ground passages outside Rome which were used for burying the dead. It was probably at this time that Peter and Paul were put to death in Rome.

For nearly 200 years after the persecutions by Nero the Roman government made no strong effort to stamp out Christianity. Christians, to be sure, were regarded as outlaws who were liable for punishment, but there were no general persecutions. By 250 A.D., however, the persecution of Christians began again in earnest. At that time the Empire was torn by civil wars and invaders threatened along the frontier. Here was trouble and Christians were blamed for it. The old gods, so the argument ran, were angry with Rome for letting so many people neglect them. Two Roman emperors used this argument as an excuse for persecuting the Christians. They ordered that all Christians were to give up their religion and return to the worship of the old gods. Many of the Christians who stuck to their faith were punished. Their property was seized. Some were compelled to work in the mines or stone quarries, which meant a slow death. Others were cruelly executed, but such attacks were short-lived and ended when the emperors who started them died.

Persecutions failed to crush Christianity. Meanwhile Christianity, despite persecutions, continued to spread. By about 300 A.D. perhaps a tenth of all the people in the Empire were Christians. The majority were humble folk, but some were soldiers, nobles and high government officials. No longer were the Christians a hunted and despised group of people with no influence. No longer were they generally regarded as disloyal and dangerous. Moreover, many non-Christian Romans eyed the Christians with increasing respect and sympathy. So another great persecution in the early 800’s failed. In a large part of the Empire, officials made no attempt to carry out their orders to punish Christians. Persecutions ended officially in the year 311. After that year Christians had no further need to keep their worship secret.

Christianity became the official religion of the Empire. During the rule of Constantine, Christianity made great progress. According to an old story, Constantine saw a vision of a cross blazing in the sky. After adopting the Christian cross as his battle emblem, he was victorious over a powerful rival. Whether or not the story is true, Constantine realized that faith in the old gods was dying while Christianity was growing stronger. Constantine therefore reasoned that by favouring Christianity he would strengthen his empire and increase his own power. An order was issued in 313 A.D. placing the Christian religion on an equal footing with the old Roman religion. Shortly afterward, Christianity became the official religion of the Empire. The temples of the old gods were closed or turned into Christian churches. And by 400 A.D., worship of the old gods was declared to be against the law.

Christians developed a church organization. The earliest Christians had been scattered and few in number. In each town the group of Christians was led by a bishop, or overseer. These bishops, the Christians believed, had received their authority from the first disciples and missionaries; therefore they should be listened to with respect. As the number of Christians multiplied, however, a more definite and close knit church organization became necessary. In many respects this organization was similar to that of the Roman government. To take care of new groups of Christians within each local area, or parish, the bishop appointed priests, or pastors (from the Latin word meaning “shepherds”). All the bishops within each province were brought under the authority of the bishop in the capital city of the province. In Italy and elsewhere in the western part of the Empire, these bishops-in-chief became known as archbishops.

The Bishop of Rome became the Pope. In time Christians in the western part of the Empire — ordinary Christians as well as priests, bishops, and archbishops– came to regard the bishop in the city of Rome as supreme. They were used to thinking of Rome as the center of authority. Furthermore, they believed that Rome’s first bishop had been Peter, the chief of the original apostles and that all bishops of Rome who came after Peter inherited their authority from him. Not until nearly 1100 A.D., however, did the title Pope (from the Greek word papas meaning “father”) come to mean only the Bishop of Rome.

Eastern Christians were led by patriarchs. In the eastern half of the Empire, the bishops in chief were called metropolitans, not archbishops. But there was no single chief metropolitan to whom all eastern Christians looked for leadership as Western Christians did to the Pope. Instead, there were several important metropolitans, or patriarchs. The patriarchs could not always agree among themselves or with other clergy, so there was no real unity in religious matters.

The emperors took part in religious affairs. Constantine had hoped that Christianity would help to unite his Empire, but bitter disputes among clergy in the eastern part of the Empire alarmed him. So in 325 A.D. he called a great council, or meeting, of bishops from all parts of the Empire in the city of Nicaea in Asia Minor. The Council tried to end disputes by issuing a statement of Christian belief. This statement is called the Nicene Creed and is today, with minor changes, the basis of Christian belief.

Later emperors called other councils of high clergy from time to time. Some rulers even tried to force their own ideas upon the clergy, but with little success. For example, the Emperor Valens ordered Archbishop Basil of Caesarea to change his religious views. When Basil refused, the Emperor’s messenger threatened him with death. But Basil replied, “Do your worst, . . . You cannot exile me from the grace of God; and death will but bring me the sooner into His blessed presence . . . Where the cause of God is at stake . . . fire, sword, wild beasts, have no terror for us.” The story may be only a legend, but it reminds us that many early Christians were willing to die for their beliefs.

Christians slowly divided into western and eastern organizations or Churches. As you have just read, the Bishop of Rome, later known as the Pope, became undisputed head of the Christians in the western part of the Empire. He also claimed the headship of the Christians in the eastern part of the Empire, but the patriarch in the important city of Constantinople challenged this claim. In time, therefore, Christians in the Eastern Empire began to think of the patriarch in Constantinople as their leader.

Other differences helped to separate western and eastern Christians into two groups. Greek was the language of the majority of the people in the Eastern Empire, so Greek was used there in church services just as Latin was used in church services in the Western Empire. Further division came over such matters as (1) church ceremonies, (2) celebration of church holidays, and (3) rights of the clergy. In the long run, these differences divided Christians into two large bodies: the Roman Catholic Church in the West and the Greek Orthodox Church with its offshoots — the other Orthodox Churches of eastern Europe and the Near East.

Monasteries appeared in the East and West. Among Christians, then as now, were some people who wanted to get away from the world about them and to devote their lives to God. Such people preferred to lead lives of prayer, fasting, and poverty. Like hermits they hid themselves away in deserts or lonely places. This practice was particularly common in Egypt, but spread widely in Syria as well. Groups of men began living, together in simple quarters where they carried on their prayers and fasts. Such places are called monasteries, and the men who live in them are called monks.

Various sets of rules were drawn up to regulate the lives of the monks. Famous among the early ones was the rule of St. Basil, the same man who defied the Emperor’s official. Basil’s followers were expected to live and eat together in a group and to share a common work and common worship. They were to do hard manual labour as well as pray. About 500 A.D. St. Benedict laid down somewhat similar rules for the order of Benedictine monks. The famous monastery founded by St. Benedict at Monte Cassino in Italy was destroyed in World War II. It has since been restored.

Nuns, or women who wished to live similar lives of prayer, lived together in convents. As time went on, more people became monks and nuns. These unselfish and unworldly men and women played an important part in the life of the Christian Church, both Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox. They preserved much of what was best of Greek and Roman civilization. They carried this civilization as well as Christian teachings to barbarian tribes in western and eastern Europe. In them burned the twin flames of faith in their religion and of service to others.

3. What did the Byzantine Empire Contribute to Civilization?

The story of Andropolos, tells how the West declined and came under the Teutons and how Christianity rose and spread. Why Andropolos looked forward to his return to Constantinople. What, in short, was life like in the Byzantine Empire?

Constantinople outshone all other cities in the Byzantine Empire. Just as Athens was the key city of Greece and as Rome was the hub of the Roman Empire in its days of glory, so the life of the Byzantine Empire centered in its capital city, Constantinople. There are five points to keep in mind about this old imperial city: (1) Constantinople was a large city, with a population of over 500,000 people. (2) Constantinople was a strong city. It lay on a peninsula with three sides protected by water and its land side defended by massive walls. For hundreds of years it defied all attempts to seize it or starve it into submission. (3) Constantinople was a busy city because of its geographical location, it became the centre of trade routes running in all directions. Its shops and craftsmen produced a large variety of useful and beautiful goods. (4) Constantinople was a gorgeous city, with magnificent churches and public buildings which ranked among the finest in the world. (5) Constantinople was an exciting city. Lavish ceremonies and entertainments were held in honour of the emperor. Among the most exciting were the four horse chariot races that were run in the huge Hippodrome, which seated over 50,000 persons.

The Byzantine emperor was all-powerful. Over the colourful city of Constantinople and the empire that it dominated ruled the emperor. The word autocrat (all powerful ruler) describes him perfectly. He made the laws and appointed officials to enforce them. He set tax rates and sent representatives to collect tax payments. He commanded the army and navy. He controlled the Eastern Church and usually selected the Patriarch of Constantinople. He decided all government policies and selected the man who should succeed him as emperor. In fact, one such successor was chosen before he was born! Of course the emperor was assisted by high officials who headed the departments of government and supervised the clerks and other workers.

The Institute of Justinian

Justice is the set and constant purpose which gives to every man what is due him. . . . The principles of the law are these: to live honestly, to injure no one and to give every man his right. . . . The laws of nature, which are observed by all nations alike, are established, as it were, by divine providence and remain ever fixed and unchangeable. But the civil laws of each individual state are subject to frequent change, either by the silent consent of the people, or by the later enactment of another law.

In general, this system worked efficiently. It provided justice and order. A set amount of taxes was collected regularly, and so the emperors had steady income –something no other ruler had in the Christian world at that time. As a result, the emperors had funds for armies and navies and public improvements. In time of need, they could buy military support from other rulers. Great wealth enabled the emperors to live in a luxurious fashion that impressed citizens and foreigners alike. Inspite of their unlimited power and riches, however, incapable or unjust emperors ran the risk of being murdered.

Byzantine law was largely Roman law. You will recall the great law Code of the Emperor Justinian. It was published in Latin, the official language of the government, but even Justinian had to publish later laws in Greek, since most Roman citizens of the Eastern Empire used that language. Several revisions of the Code were made by later emperors. All of these were in Greek, but they preserved the ideas and practices of Roman law. The growth of Christianity, however, led to changes in the law to provide better protection for wives and young children.

The Byzantine armed forces were efficient. The Byzantine Empire had to fight off the SIavs, the Persians and the Mohammedans or Moslems. Its army was small, but the men were well trained and equipped. Officers depended on careful planning and the science of warfare rather than on sheer weight of numbers. The Byzantine navy also was efficient. It possessed a secret weapon, the so-called “Greek fire.” This was a mixture of naphtha, oil, pitch and other materials which burned fiercely even when wet. Compressed air shot this fiery mixture from gun-like tubes on Byzantine warships and crews threw grenades filled With it. “Greek fire” helped Byzantine fleets defeat much larger forces, though it would undoubtedly seem ineffective in comparison with modern flame throwing weapons.

By about 1100 A.D., however, Byzantine rulers began to neglect their armed forces. This failure led finally to the downfall of the Empire and the capture of Constantinople by Moslems in 1453.

Industry and commerce flourished. The Chief reason for the prosperity of the Byzantine Empire was its extensive trade. To Constantinople flocked merchants from Persia, Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, Russia, Hungary, Italy, Spain and many other lands.

The chief export of the Empire was silk goods. In the time of Justinian, two Christian monks brought from China cocoons of the silkworm concealed in hollow canes. Silk could now be produced within the Byzantine Empire and the manufacture of silk and silk goods was carried on under government control. Chinese silks coming over the long caravan routes could not compete with those made in the Empire and since the silk routes from China ended within the Empire, Byzantine rulers also controlled the Oriental trade in silks.

Other Byzantine products in great demand were woolen fabrics, salt and weapons. Skilled craftsmen produced richly decorated bowls of gold and silver, carved ivory ornaments for churches or the homes of kings and nobles.

Byzantine trade was aided greatly by Byzantine money. The standard coin was a gold piece worth a little under six dollars in our money. Its value remained unchanged for over 700 years. This coin, the bezant, was in great demand among other peoples and circulated freely in western Europe.

Byzantine schools taught many subjects. Byzantine education began with word of mouth religious teaching at home. When old enough, children of those parents who could afford it were sent to an elementary school to learn reading, writing and some arithmetic. Greek was spoken in the classroom and the schoolbooks were written in Greek. It was the Greek of old Athens, which differed somewhat in pronunciation and grammar from the Greek commonly spoken in the Byzantine Empire.

Many boys then went on to secondary schools where they studied literature, music, geometry and astronomy. After the secondary school, students frequently attended a university to learn public speaking and philosophy. Besides the universities, there were special law schools and schools for advanced training in medicine The most famous university and law school were in Constantinople. In addition to the ordinary schools, there were the schools at the monasteries. These were intended for men who wanted to become priests or monks.

A great deal of earlier Greek literature and philosophy was preserved. Ancient Greek literature was read and studied widely in the Byzantine Empire. For this reason numerous copies of the works of famous writers of earlier days were made for schools and libraries. In such fashion these ancient writings were preserved and centuries later many of them reached Italy and other Western countries.

Imitating earlier historians, some Byzantine authors wrote detailed histories of events of their own day. Others compiled lists of dates and important events from the distant past to their own times. To them we owe a great deal of our knowledge of Greek and Roman history, but few contributions of importance were made by Byzantine scholars in scientific studies. Progress in astronomy and geography declined because, people said, it was contrary to Christian teachings to believe the world was round and not flat.

Byzantine art was closely linked with religion. Christianity played a great part in the lives of the Byzantine people. It was only natural, therefore, for them to use their artistic abilities for religious purposes. Constantinople itself was a city of many churches. Most splendid of them all was St. Sophia, the great Church of the Holy Wisdom, one of the triumphs of Christian architecture. This church still stands.

The domed style of architecture employed so successfully in St. Sophia was used almost everywhere. Generally, more attention was paid to the interior than to the outside appearance of Byzantine churches. While the outside remained plain, the interior walls and the ceilings were richly decorated with paintings and coloured mosaics — pictures made from bits of coloured stone cemented together. These pictures not merely added beauty and colour to the churches; they also taught the story of Christianity and its beliefs to the worshipers.

Byzantine people were famous for another form of religious art, icons. Icons are pictures of saints or other persons important in Christian belief. The icons were hung in churches, chapels and monasteries as well as in private homes. Throughout the Eastern Orthodox Church they were very popular. Some were the work of superb artists, others were gaudy and poorly done. Perfect or not, the icons showed how close religion was to the Byzantine people.

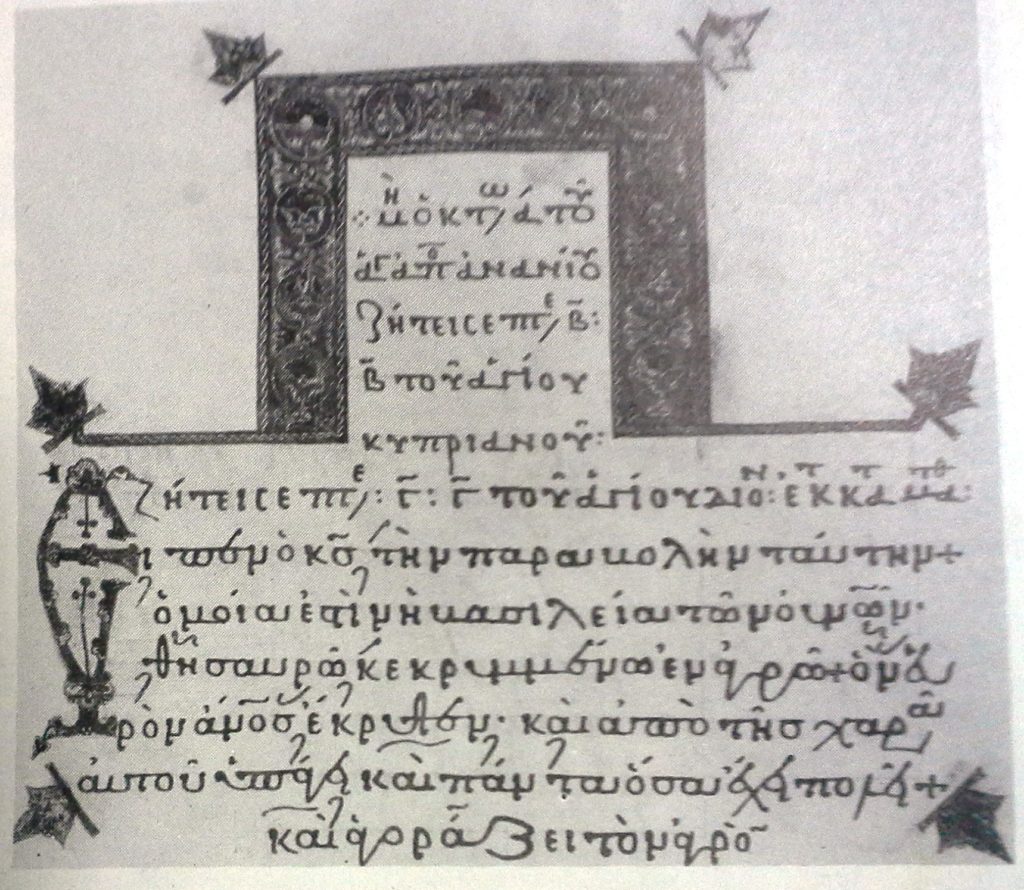

The icons were products of the monasteries. Here, too, were prepared beautiful manuscripts of the Bible and other writings copied on parchment. These manuscripts decorated with ornamental letters and tiny colourful paintings, are called “illuminated.” Illuminated manuscripts are regarded as great treasures in our libraries and museums today.

The work of Byzantine artists was in great demand among outside peoples. Many Byzantine artists and architects worked in western Europe and the Slavic lands, especially Russia, where Byzantine art forms are still used.

Civilization was preserved and advanced. Although in later centuries the Roman Empire could not boast the power and influence it had possessed under the early emperors, it continued to be a stronghold of civilization. Christianity spread to most of its people and was carried by monks to the Teutons and Slavs. After the West was lost, the Roman Empire of the East (the Byzantine, Empire) remained the great centre of Christian civilization. It preserved and passed on to Europeans of later times not only Greek and Roman ideas but its own civilization as well.