LOUIS PHILIPPE always spoke of himself humbly as the “citizen king.” Although he was dignified, friendly and tried to do things that would make him popular, his government could not satisfy the needs of the people. The reason was that only one out of every thirty Frenchmen had the right to vote. The Chamber of Deputies represented only the nobles and the rich upper crust of the middle class and often it did not even debate questions that were of importance to the great majority of the people.

Many Frenchmen did not like the new king. The republicans were opposed to having any king at all. The “liberals” — people of the middle class who favoured a constitutional monarchy thought his government was too conservative and did not allow enough freedom. As the years passed, more and more Frenchmen, including the workers in the cities, turned against him because he refused to support their demand for the right to vote.

The liberals were forbidden to hold meetings at which they could present their demands. To get around this, they decided to follow the British system of holding political banquets. At the first of these, held in Paris in the summer of 1847, they demanded that the election laws be changed to include most of the middle classes. They also wanted freedom of trade and of the press. The banquet was so successful that similar gatherings were held in almost every town in the nation.

Then the liberals announced that a great banquet, with a parade and demonstrations in the streets, would be held in Paris on the night of February 22, 1848. When the government refused to allow it, the angry people of Paris gathered in the streets. They milled about, not knowing what to do, for no plans had been made for an uprising and they had no leader.

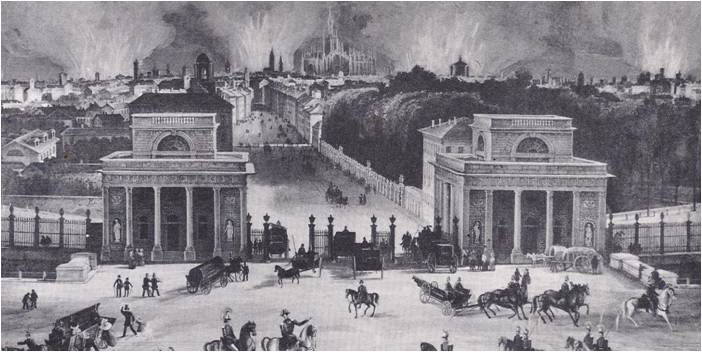

The following day, the theatres remained closed and few persons went to work. The crowds grew larger and more restless. Everyone felt that something was about to happen, something explosive, decisive and terrible. To avoid trouble, Guizot, the prime minister, resigned; now a more liberal minister could take his place. The news of Guizot’s resignation quickly spread to all parts of the city and people of the middle class began celebrating. Women and children went about forcing people to join the celebration by putting lighted lamps and candles in the windows of their homes, but the workers were not satisfied with a change in ministers. They had taken part in the revolt of 1830 without winning the right to vote and they did not mean to be fooled again.

A group of workers marched to the Ministry of Justice that evening and demanded that all the windows in the building be lit up. When they set off for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, thousands of persons followed them. Near the building of the ministry they were stopped by soldiers. The officer in command ordered the troops to fix bayonets and as the crowd surged forward, someone fired a shot, probably by accident. The nervous soldiers thought they were being attacked; they lifted their muskets as if by command and fired directly into the crowd. The frightened people scattered, leaving the dead and wounded behind them on the bloody pavement.

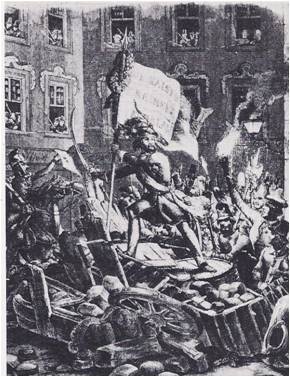

The wounded were soon hurried into the nearby shops and houses and a large wagon drawn by a white horse was brought up and piled high with the dead. A group of people with torches led the wagon all over the city that night. They knocked on the doors of the poor, making sure that everyone would see the bodies and know what the king’s soldiers had done.

Church bells rang and it seemed as if all Paris was rushing into the streets and building barricades. More than 1500 barricades were thrown up; some, at the main intersection, were two stories high. Four-foot-square paving stones, iron balcony railings torn from houses, lamp posts, wagons, boxes, furniture, trees cut down along the boulevards — anything movable was piled on the barricades and the streets looked as though they had been struck by a tornado.

King Louis Philippe grew more frightened with each passing hour. To prevent bloodshed, he was forced to remove the regular army from the city. The National Guard was left to keep order, but he could not depend upon it because it sympathized with the people. In the end Louis Philippe gave up his throne and fled with the royal family to England.

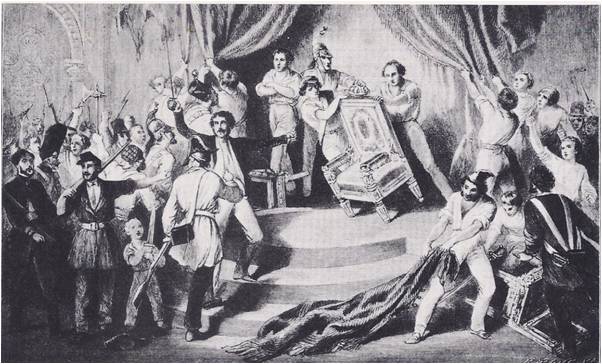

Shortly after the king had left the Tuileries, as the palace was called, mobs broke in and began helping themselves to anything they could carry off. They found that the table had just been set for lunch and that the food was still hot. Some of them sat down with a great show of elegant manners and ate and laughed their way through the royal meal. Someone put up a sign that read: “House for Rent.” Most of the mob seemed to enjoy smashing glass — they broke about 23,000 pieces of glassware — and they took turns sitting on the royal throne.

There were still a number of Frenchmen, including some members of the Chamber of Deputies, who wanted a king at the head of the government. When they planned to crown the young son of Louis Philippe, the republicans, supported by the radicals, refused to allow it. Storming the chamber, they insisted France be proclaimed a republic. A temporary government of ten men was set up with instructions to arrange for the election of a Constitutional Assembly. The Assembly would then meet and draw up the constitution of the Second French Republic.

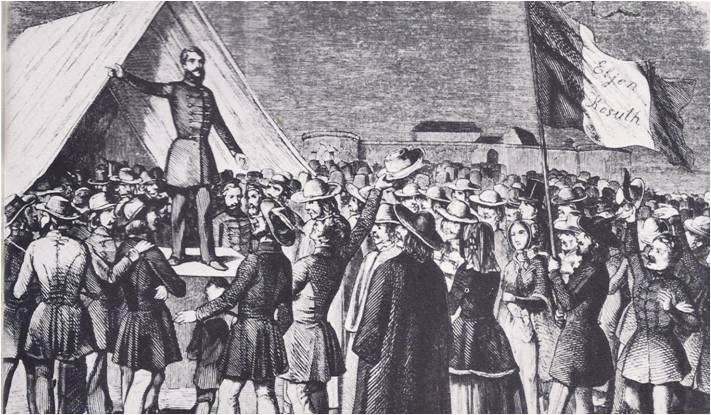

News of the quick success of the French revolution surprised and encouraged liberals and radicals in all parts of Europe, particularly in the small countries that made up the Austrian Empire. In Hungary, Louis Kossuth made a stirring speech about liberty. The speech was read in Vienna, the capital of the empire, where people were already excited by the word from Paris. Workers and students built barricades, fought off the soldiers and broke into the royal palace. Prime Minister Metternich resigned and escaped from the country in disguise.

Metternich’s flight proved to the liberals of Germany and Italy that the Vienna government was no longer effective. Riots swept Berlin on March 15 and the governments of the smaller German states fell one by one. Hungary continued to recognize the emperor of Austria, but demanded a constitution of its own. The Czechs demanded national independence. The Italians drove the Austrians out of Milan. Venice broke its ties with Austria and declared itself to be independent. The king of Sardinia declared war on Austria and received the help of Italian soldiers from all parts of Italy. In the north, the small German states made plans to form one large German nation and the Prussian king promised his people a constitution.

The lower classes in most of these countries were not prepared for democracy. The great majority of peasants had no education and could not understand the meaning of revolution and democracy. Those who were serfs thought only of winning freedom from their landlords; once they had won such freedom, they cared for nothing else. The men who led the revolutions were few in number and soon they were left to carry on almost alone, with little support from the people. When they tried to set up new governments and determine where boundary lines should be drawn, they began quarreling among themselves. The Austrian Emperor sent his army against them and one by one brought their countries back under his control. In German and Italy the ruling classes proved strong enough to put down the revolts.

The word “liberal” has meant different things in different periods of history. During the period of the 1848 revolutions, liberals wanted the vote for all members of the property — owning clan, industrialists, merchants and bankers as well as the aristocrats — but they opposed giving the vote to the common people. They favoured reform rather than revolution, constitutional monarchy rather than democracy.

Yet, although the revolutions of 1848 failed, Europe would never again be quite the same. Serfdom in central Europe had been brought to an end; the peasants were free at last. The feeling of nationalism was strengthened, particularly in Germany and Italy. Class hatred increased. Metternich, who had guided Europe for many years, was in exile and the kings, nobles and wealthy had no leader around whom they could gather. The people had learned a lesson — revolution was not always a successful method of gaining what they wanted. They began to seek more practical ways; they began to consider the British method of advancing toward democracy gradually through the law-making body of the government.