The postwar stirring of nationalism among peoples in Asia and Africa, was one important outcome of World War 2, but World War 2 created another great yearning that was world-wide, the desire for a firm and lasting peace. This greatest of all conflicts had uprooted millions from their homes, destroying their means of livelihood. It had brought death, sorrow and a great war-weariness. News of the Allied victory in 1945 was received in a spirit of quiet relief and hope for the future.

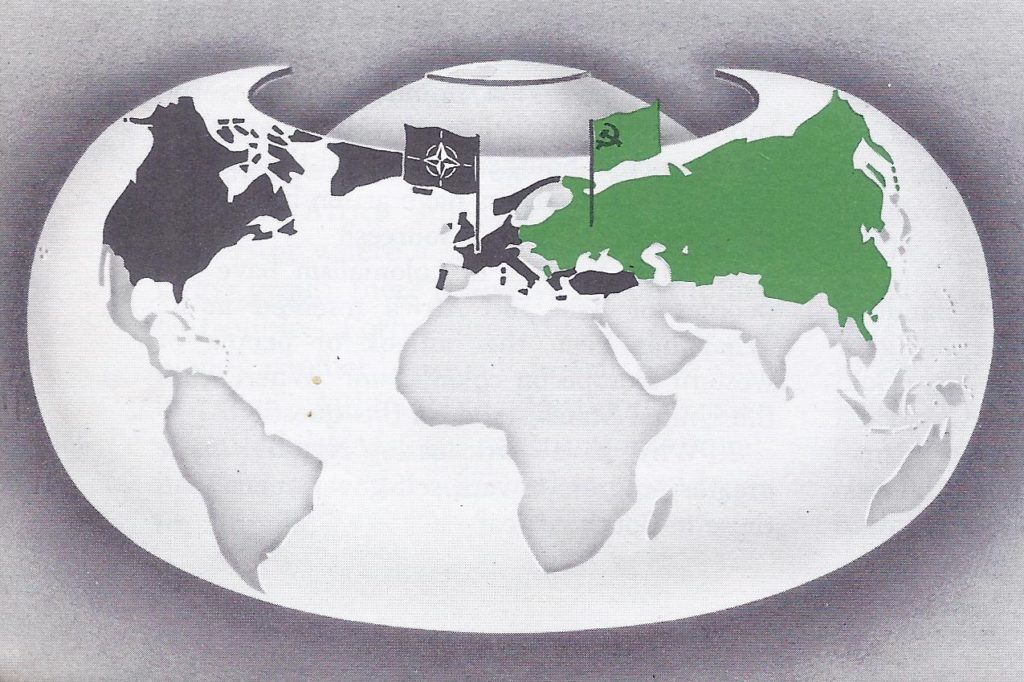

The hope for peace met disappointing setbacks in the years that followed. Instead of working together, nations split into three camps — the free world, the Communist world, and the neutralist countries. As a result of Soviet policies, a “cold war” of words and threats developed. This “cold war” turned into armed conflict when United Nations forces came to the defense of the Republic of Korea. Communist-inspired crises also broke out in many other parts of the world.

Problems plagued the world in recent years and the United States played a key part in the strengthening of the free world and in the search for peace. We get a glimpse of the awe-inspiring challenges of tomorrow’s world. These matters will be taken up under the following topics:

- How did the postwar world become divided?

- What steps did the free world take to meet the threat of postwar communism?

- What did the postwar future hold?

1. How Did the Postwar World Become Divided?

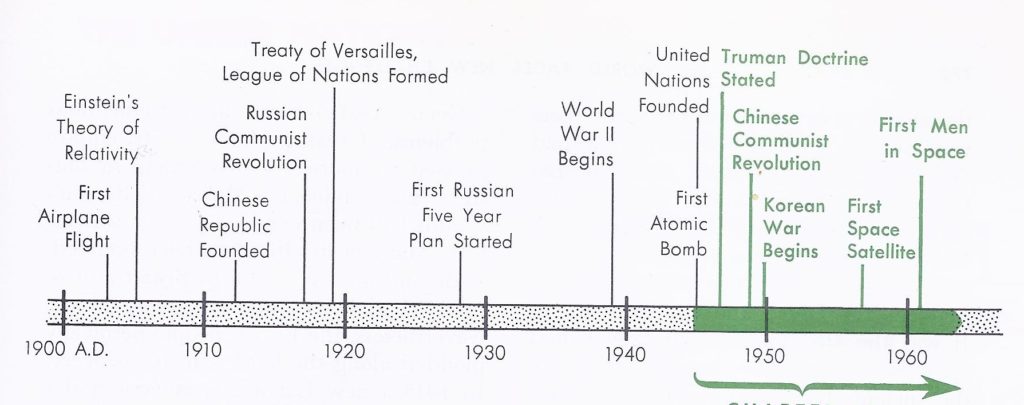

Victory in World War 2 would not have been possible without close teamwork among the nations fighting the Axis powers. Then, in 1945, while the combined armed forces were crushing Germany and Japan, the United Nations was organized. The outlook for continued co-operation in peacetime seemed bright.

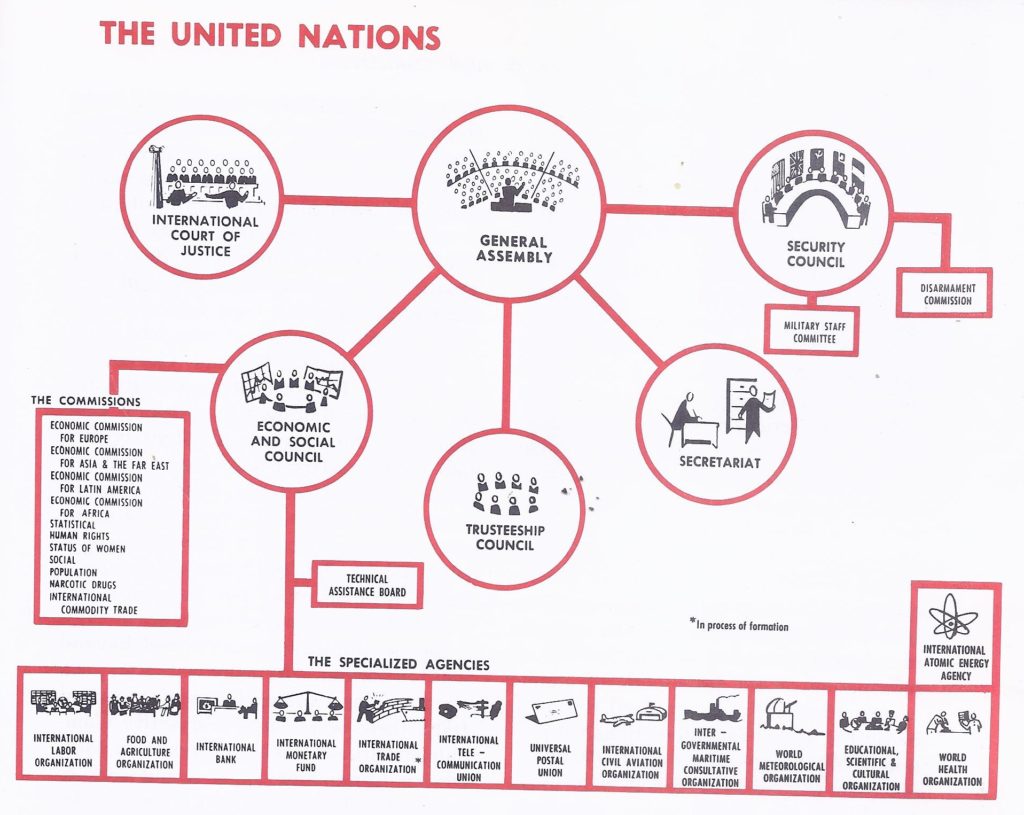

The United Nations got under way promptly. The first session of the UN General Assembly took place in January 1946 in London. Shortly thereafter the United Nations moved its headquarters to the United States. In 1952 it gained a permanent home — a cluster of new buildings fronting on New York City’s East River.

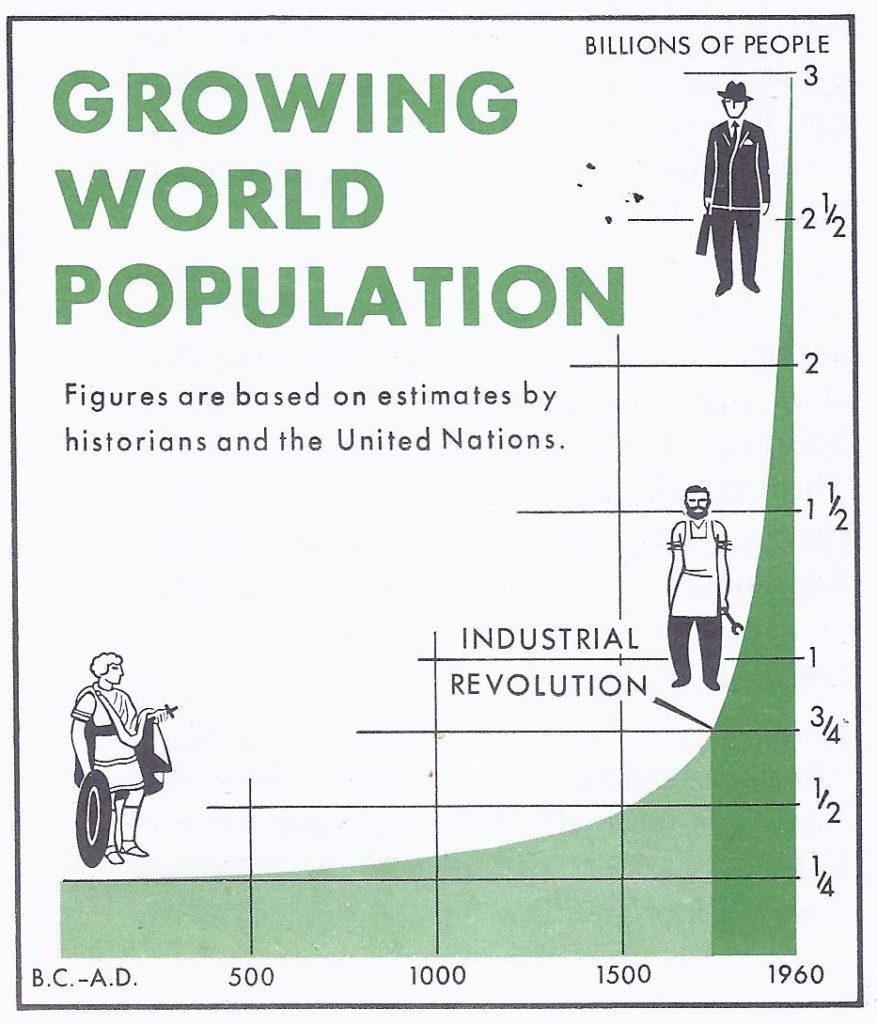

Many of the UN’s activities deal with humanitarian problems. In the postwar world, millions of people were without food, homes and jobs. Moreover, even in normal times two thirds of the world’s people not only lacked many things which Americans take for granted but did not have enough to eat. Millions had no opportunity to get an education and lacked the technical skill to improve their lot. Improved living conditions would not only relieve human suffering but might help to prevent future wars. It was to deal with such tasks that the UN Economic and Social Council was created.

A number of permanent special agencies were to assist the Economic and Social Council: (1) the World Health Organization (WHO), to improve health conditions among all peoples; (2) the International Labour Organization (ILO), to bring about better labour conditions through international cooperation; (3) the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), to raise nutrition levels through greater production and better distribution of food; and (4) the Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), to promote cooperation among nations in the fields of education, science and culture. In addition, the Economic and Social Council has been assisted by commissions, some continuous, others appointed for special tasks.

The United Nations has averted several threats to world peace. In the minds of most people, the United Nations’ foremost responsibility was to maintain world peace. Since its early years the UN has settled or eased several situations that threatened to bring on war. UN observers were sent to Kashmir, where trouble had developed between India and Pakistan. The United Nations also helped to bring about the withdrawal of Russian troops in Iran and on two occasions (1949 and 1962) to solve differences between the Dutch and the Indonesians. It was the UN, too, that in 1949 halted open war between the Jews and Arabs in the ancient Holy Land and helped to settle the Suez Canal crisis.

The United Nations has met with obstacles to its peace efforts. Soon after its founding, however, it became apparent that the United Nations could not always operate effectively. One difficulty arose in the Security Council. Under the UN Charter the United States, Britain, Russia, France and China were to be permanently represented on the Council. Any one of these permanent members, by voting “No,” could defeat a proposal brought before the Security Council. It was possible, therefore, for a single power to block an important action favoured by the majority. Between 1945 and 1950, Russia used its veto 74 times; France, only twice; Great Britain and the United States, not at all.

Underlying the abuse of the veto power was a far more serious threat to the UN’s effectiveness. This was the widening split between the Western powers, headed by the United States and the Communist world, led by Soviet Russia. To understand why this split developed, we need to take a quick glance at the postwar world.

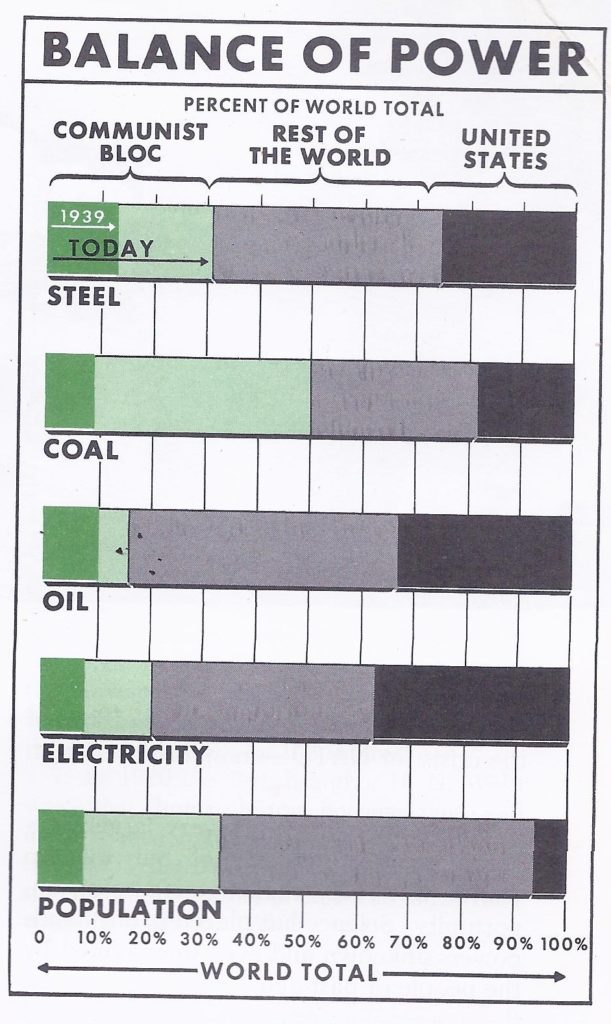

World War II changed the balance of power. World War II brought great changes in some nations which had been world powers. The three members of the Axis — Germany, Italy and Japan — had been stripped of their military power and colonial possessions. France, which had never fully recovered from World War I, had suffered grievously in World War 2. After four years of German occupation, the French people were divided and discouraged.

Even Great Britain faced tremendous problems. Great portions of its empire pressed for more self-government or outright independence. Much of Britain’s wealth had been expended in the war effort. Many of its cities had been bombed; trade and industry, vital to Britain’s prosperity, had been dealt staggering blows. Nevertheless, the British people heroically plodded along the hard road to recovery. In 1945 a new Labour government under Clement Attlee replaced the war government of Winston Churchill. This Labour government tightened economic controls by nationalizing the Bank of England, the railroads, coal mines and the steel industry.

The United States, on the other hand, had come through World War 2 stronger than ever. This country had spent billions of dollars in the war effort and had suffered heavy losses among its armed forces. but (except for islands in the Pacino) had not been bombed or invaded. To provide needed food and war materials, American production had reached a new high.

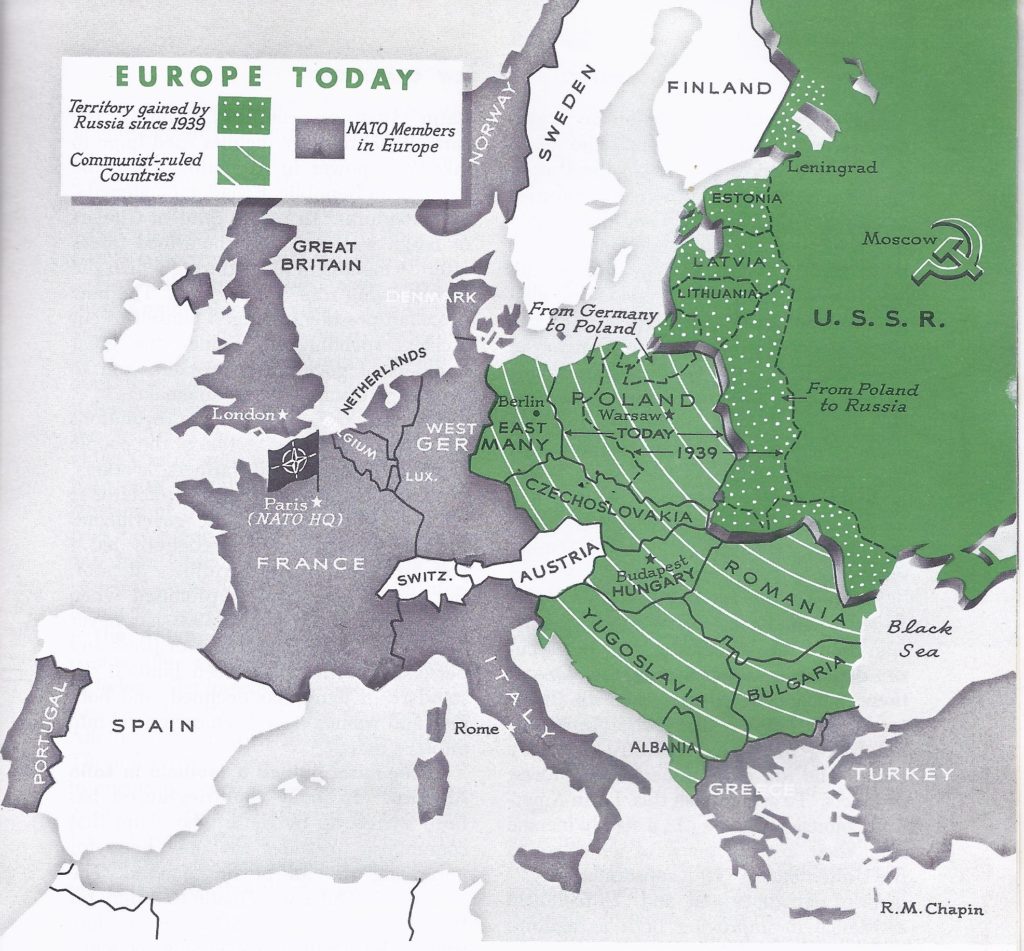

A stronger Russia emerged from the war. Soviet Russia, although it had suffered from invasion, stood out as the other great world power in 1945. The Soviet Union had reclaimed lands lost during World War I, including Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, large parts of Poland, Finland and Bessarabia. It also took two new pieces of territory the northeastern tip of Prussia and the eastern end of Czechoslovakia. Altogether, these gains amounted to an area larger than all of France.

Soviet Russia’s influence actually extended far westward into Europe — to lands occupied by Communist armies during World War 2. When the war was over, Soviet forces remained in these conquered lands. Russian-occupied areas included the former enemy countries of Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, part of Austria and one third of Germany.

Between the two World Wars, moreover, Russia had greatly expanded its industry. Although Hitler had heavily damaged Russian industry, production was stepped up at the war’s end. Soviet production, however, was geared to military needs rather than consumer goods. Postwar Russia had the largest army and air force in Europe and had begun developing an atomic bomb.

The Soviet Union held a permanent seat in the Security Council and had three votes in the UN General Assembly. (The Soviets claimed for two “republics” in the Soviet Union — the Ukraine and White Russia — the same representation given such independent members of the Commonwealth of Nations as Canada.)

Soviet policies resulted in a divided world. After 1945 it became increasingly evident that the Soviet Union would make no agreements which interfered with its policies. The Soviet government’s attitude was made clear by (1) its tactics in the United Nations, (2) its policy in eastern Europe, (3) its reactions to American efforts to help Europe and (4) its plans for Germany.

Russia blocked action in the United Nations. The USSR often used its veto power in the UN Security Council. The Russian delegates also developed the habit of “walking out” of meetings when they did not like the way things were going. Such tactics blocked many proposals. As tension mounted, neither Russia nor the Western powers would agree to admit nations to the UN which might add strength to the opposing side.

On most issues, east European countries lined up with Soviet Russia; Latin American and west European countries lined up with Britain and the United States. In time, certain countries thought of themselves as bound to neither group. The delegates of such neutralist states as India, the Arab states and many former European colonies in Asia and Africa did not consistently support either side.

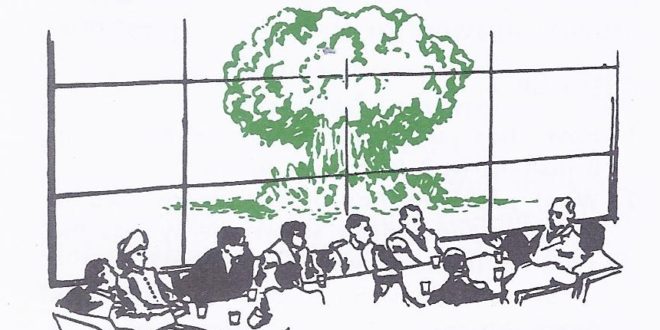

The most serious result of Russia’s refusal to cooperate in the United Nations was the failure to reach agreement on control of the atomic bomb. As early as 1946 the United States had proposed to give an International Atomic Energy Authority complete control over all uses of atomic energy. If the proposal were accepted, the United States would destroy its stockpile of A-bombs and hand over to the UN all information on the production of atomic energy. Soviet Russia opposed this plan because it called for international inspection of all atomic energy plants. A different plan proposed by Russia was unacceptable to the United States. After two years of fruitless discussion, a race developed between the two countries to develop increasingly deadly nuclear weapons.

The Soviets shut off eastern Europe behind an “iron curtain.” To create a ring of buffer states and to extend communism, Russia brought about sweeping changes in eastern Europe. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were made “republics” within the Soviet Union. Russian-backed Communist groups worked to make satellite states of Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia and Albania. The first step was to set up governments in which various parties were represented. Later, the Communists ousted the other parties and took over. The situation was particularly tragic in Czechoslovakia, which had been the most democratic state in eastern Europe.

Whether once independent states were incorporated in the USSR or were ruled by native Communist dictators, all were confined behind an “iron curtain” of censorship. East of a line extending from the Baltic to the Adriatic Sea, no books, magazines, or newspapers could be published or imported that criticized either the Soviet Union or communism. Frontiers were guarded to prevent dissatisfied persons from escaping. Few foreigners were admitted and spies watched those who were, including diplomats. The only Communist country in Europe not under Russia’s thumb at the time was Yugoslavia. Marshal Tito, the Yugoslav dictator, did not like taking orders from Moscow. Yugoslavia remained outside Russian control, though retaining a Communist government. In other eastern European countries, Russia “purged” local Communist Party members who put their own nation’s interests ahead of Russia’s.

Communist activities extended beyond the iron curtain. In many west European countries and especially in France and Italy, there were large and active Communist Parties. Taking orders from Moscow, a Communist Party would seek to embarrass the government in power by blaming it for the slow recovery from destruction and want caused by the war. The solution to postwar problems, the Communists declared, lay in communism. Nevertheless, Italians in 1946 voted to establish a democratic republic and France drafted a new republican constitution. Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Holland restored the constitutional monarchies which Hitler had driven from power.

The Soviet Union spurned the Marshall Plan. Meanwhile, the people of Europe were heartened by America’s continued interest in European problems. World War 2 had convinced most Americans that their peace and prosperity were endangered if insecurity, fear and want existed elsewhere in the world. If peace was to be assured, therefore, war-torn Europe must regain its prosperity.

In June 1947, the American Secretary of State, George C. Marshall, voiced a proposal: If European nations would work out plans to repair war damages and expand industry and trade, the United States would help to bear the cost. This proposal came to be called the Marshall Plan.

At first, some Communist countries in eastern Europe seemed interested in the Marshall Plan. Then Moscow declared that it was merely a scheme to increase American influence in Europe. Representatives of sixteen western European countries, nonetheless, met in Paris to arrange for putting the Marshall Plan into effect. By 1955, production in most western European countries was greater than before World War 2. The Marshall Plan contributed a great deal to this remarkable achievement.

Russia blocked a settlement in Germany. Communist Russia also refused to cooperate with its wartime allies in arranging a peace settlement for Germany. At the close of World War 2, Soviet forces controlled Germany east of the Elbe River, while Britain, France and the United States had occupation zones in western Germany. All the powers had agreed that Germany should be reunited and that an election should be held to choose a government, but Soviet Russia rejected every Western proposal for reunification.

Matters in Germany came to a climax in 1948 and 1949, when Russia blocked land and water communications between Berlin and the West. Berlin, though east of the Elbe River, was jointly occupied by Russian and Western forces. Russia bluntly presented two choices to the Western powers: (1) They could surrender their zones in Berlin to Russia, a step which the Communists would hail as a great victory. (2) They could force their way across Russian-held territory to reach Berlin, a move that could have resulted in war. The Western powers actually chose a third course. For months huge transport planes shuttled back and forth between the West and Berlin, bringing in almost 2.5 million tons of food and supplies. When the Russians saw that their blockade had failed, they gave in, permitting trains and trucks of the Western allies once more to cross Russian-held territory to Berlin.

Germany continued to be divided. Two different governments developed in Germany – a Communist “people’s republic” in East Germany and a federal republic with a democratic government in West Germany. Russia’s plan for Germany had been not only to convert its people to communism but to gain control of Germany’s industries and skilled workers. The Russians, however, met resistance even within their own zone. Though border guards shot to kill, a growing number of East Germans fled to the freedom and prosperity of West Germany.

The cold war led to outright war in Korea. We are aware of the Communist menace in Europe and efforts to contain it; meanwhile, the Communist threat in Asia led to war. In 1950 fighting broke out in Korea, a country from which both Russian and American occupation troops had been withdrawn.

During their occupation of North Korea, the Russians had encouraged a Communist form of government. South of the 38th parallel the Americans had encouraged the establishment of a republic. Without warning, on June 25, 1950, Communist North Korean forces swept across the 38th parallel.

At the urging of President Truman the United Nations took action. The Security Council recommended that “members of the United Nations furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.” This was the first case in which the United Nations called upon its members for collective military action to uphold the UN Charter.

Hard fighting followed. North Korean forces made the most of their surprise attack. As a result, the UN army faced a long struggle to free South Korea of the invaders. South Korean and American troops made up the larger portion of the UN forces, which were commanded first by General MacArthur and later by General Ridgway.

By November 1950, the United Nations forces not only had halted the North Korean attack but under General MacArthur had driven far north of the 38th parallel. Victory seemed almost within grasp until Communist China entered the conflict. Hurling hordes of Chinese “volunteers” into battle, the Communists drove the UN forces south of the 38th parallel. The Korean War then settled down to a see-saw conflict. Negotiations to arrange a ceasefire began in July 1951, but was bogged down. The war, therefore, dragged on until a change in attitude by the Communists made a truce possible. On July 27, 1953, fighting ended in battle-scarred Korea.

The Korean truce left unsolved problems. The truce in Korea led to no permanent peace. More than ten years later opposing military forces still patrol the truce line. The UN action had repelled the invasion of South Korea, but it had not reunited Korea. Nor had it removed that country from the list of world trouble spots.

American aid has helped to repair wartime destruction and has made the South Korean army a highly effective fighting force, but the South Koreans have found it difficult to establish a stable government or to develop a sound economy. Popular uprisings in 1960 led to the resignation of 85-year-old President Syngman Rhee, leader of the Korean independence movement. The leaders who followed Rhee were, in turn, replaced by military rule.

2. What steps did the free world take to meet the threat of postwar communism?

By the end of the 1940’s Western hopes for co-operation with Communist Russia and the countries under its control had dimmed. The “cold war” which had developed threatened to burst into armed conflict. The free nations realized that they must take steps to protect themselves in Europe, the Western Hemisphere and Asia. Thanks to its power, the United States became the leader in the defense of the free world.

President Truman promises aid to resist aggression. As the “cold war” set in, President Truman recognized that war-ravaged Europe was no match for Russian ground and air forces. Particularly desperate was the situation in Greece and Turkey, the only eastern European countries outside Communist control. In 1947, President Truman announced the Truman Doctrine: “It must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressures.” Congress promptly voted funds to help Greece and Turkey. This action not only saved these two countries from communism but gave notice that the United States would resist Communist aggression against the free world anywhere.

The United States helped to create NATO. In 1949 the United States joined with Canada, Great Britain, France and several smaller western European nations to form a defensive alliance with headquarters in France. This new organization was called the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The NATO agreement declared that “an armed attack against one or more of [the members] . . . shall be considered an attack against them all.” In case of attack, each government would take “such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed forces, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area.” By 1953 NATO also included Greece and Turkey.

The United States expanded its aid program. By the end of 1951, the Economic Co-operation Administration, established under the Marshall Plan, had spent 12.5 billion dollars to speed economic recovery in western Europe. The United States also took steps to help free nations build up their military strength. In addition, this country sent experts to help underdeveloped countries increase production and raise standards of living. Government assistance in making American “know-how” available was first proposed as Point Four in a speech by President Truman. It has become known as the “technical assistance” program.

The United States encouraged greater unity among the western European nations. For centuries Europe had been weakened by national rivalries. Quarrels over land, boundaries and tariffs led to wars, which in turn created new hatred. After World War II, co-operation between nations of western Europe seemed more necessary than ever before and was encouraged by the United States.

To increase the economic strength of western Europe, statesmen moved to reduce tariffs on imports. To illustrate, in 1948, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg formed a customs union called Benelux. The Benelux nations agreed to a free flow of goods among themselves.

Two years later the French Foreign Minister, Robert Schuman, proposed that the coal and steel production of western Europe be regulated by an international agency. France, West Germany, Luxemburg, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy joined the European Coal and Steel Community established under the Schuman Plan. In 1957 these countries formed Euratom, an agency for the development of atomic energy.

Progress was also made in unifying and strengthening the defenses of western Europe, though the pace was slow. Balked by Russia’s refusal to co-operate in a German peace settlement, the United States, Britain and France made a separate peace with West Germany in 1952. Two years later, at the urging of the United States, important new agreements were reached. West Germany’s sovereignty was recognized and she was admitted to NATO. A Western European Union was also established to include Great Britain and the six Schuman Plan nations. The purpose of this Union was “collaboration in economic, cultural and social matters and for collective self-defense.”

Western European nations form a Common Market. France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxemburg planned still further co-operative action. They expanded Benelux into the European Economic Community, often called the Common Market. Trade barriers were to be removed gradually in order that goods produced by any of the six nations could be sold freely in all member countries. The success of the European Community is evidenced by the fact that between 1958 and 1963 industrial production in these countries increased by 41 percent and trade between members increased by 130 per cent.

Other western European nations feared that their trade with the Common Market nations would suffer. Some, including Great Britain, sought to be connected with the Community, but Britain’s position was made difficult because of its close commercial ties with other members of the Commonwealth of Nations. After prolonged discussions with the Common Market nations, Britain was refused admission.

The evolution of the Common Market as a third great industrial world power has raised standards of living in western Europe. It also has provided a powerful force to check Communist expansion. Still another effect has been to provide greater competition for American products. As a result, the United States Congress in 1962 passed a Trade Expansion Act, giving the President sweeping powers to adjust tariff rates. It was hoped that negotiations would bring about substantial tariff reductions and an increase in world trade.

The United States was also a member of defense pacts in the Pacific area. The cold war had led the United States to enter into defense pacts to protect western Europe from Communist aggression. Likewise, the Korean conflict and the victory of communism in China prompted efforts to increase the security of free nations in eastern Asia.

(1) In the fall of 1951 the United States concluded two defense treaties, one with the Philippines and the other with Australia and New Zealand.

(2) Japan became an important link in the free world’s defense against communism. The signing of a peace treaty in 1951 paved the way two years later for a defense pact between the United States and Japan.

(3) Finally in 1954 the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was established. Its members were the United States, Great Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand and Pakistan. The treaty called for “mutual aid to develop capacity to resist armed attack.”

Common dangers drew the nations of the Americas closer. In the postwar period the United States has sought closer relations between the nations of the Americas. The Western Hemisphere had not been ravaged by World War 2, nor was it as directly threatened by Communist attack as was western Europe. Should another world conflict develop, however, Canada could scarcely escape an attack directed against the United States. In this age of long-range missiles the shortest routes between Soviet and American territory were across the north polar region. Since World War 2, Canada and the United States have continued to co-operate for defense. Vital roads, airfields and radar networks had been built and joint air patrols maintained. The two countries were also linked as members of NATO. The co-operation between the United States and Latin America fostered by the Good Neighbour Policy became closer during World War II. When the Nazi threat loomed large, Latin America and the United States pledged themselves to resist aggression. After the United States entered the war, Latin American nations broke off relations with the Axis powers and several declared war.

The Organization of American States was formed. In 1947, when the “cold war” began, representatives of the United States and 20 Latin American countries met in Rio de Janeiro. They drew up a treaty stating that an attack on one of them would be considered an attack on all of them. A year later, at Bogota, Colombia, the plan for an Organization of American States (OAS) was approved. It provided for an Inter-American Conference every five years. Day-to-day affairs were to be carried on by a Council, in which each nation has one vote and by the Pan American Union, which acts as a permanent secretariat for the OAS. From its headquarters in Washington, the Council has acted quickly to settle disputes between member nations.

Security in our hemisphere depends on co-operation. The Organization of American States was a forward step, but security depended on other factors, too. One of these is economic co-operation. The Latin Americans were trying to expand industry, diversify crops and develop mineral and forest products. To accomplish this, Latin American countries required (1) a steady income from their exports, many of which went to the United States, (2) a substantial investment of outside capital and (3) technical assistance in improving both agriculture and manufacturing.

To achieve their goals, Latin Americans wanted help from the United States. Yet they did not want such help to interfere with their cherished independence. In the postwar years, Latin Americans felt that both their government and private business neglected their needs.

Unstable governments hampered progress in Latin America. Although business and industry boomed in parts of Latin America, better living for all was not the necessary result. Millions of Latin Americans increasingly demanded both, a better life and a greater share in their government. Economic and political crises were frequent in some Latin American countries. During the early 1960’s military regimes used force to take over power in Argentina, Peru, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala and Honduras. In 1964, President Goulart of Brazil was ousted by the armed forces after 31 months in office during which the cost of living rose 300 per cent. The new Brazilian president pledged himself to cut reckless spending, to reduce the great numbers of government workers and to get rid of Communist troublemakers.

Some recent Latin American revolutions have involved a cross section of the people — middle class, small farmers, workers, students, but the ousting of a dictator is no guarantee of democratic government. In Cuba, Fidel Castro successfully led a popular revolt against a ruthless dictator, but the general election promised when Castro came to power in 1958 was never held. Instead, freedom of press and personal liberties were limited, the standard of living declined and both men and women were organized into military units.

Communism gained a foothold in Latin America. In many countries, unrest was stirred up by those who claimed that communism provided the only hope for improving the lot of the masses. The situation in Cuba was “made to order” for the Communists. When Castro ran into trouble in carrying out sweeping economic reforms, he blamed “Yankee imperialists” for Cuba’s troubles. Soviet Russia quickly arranged a trade treaty giving Cuba oil and machinery in exchange for sugar. Moscow also declared that the Monroe Doctrine was dead and that Cuba could count on Soviet military assistance if attacked by the United States.

The prospect of a Communist base in the Western Hemisphere deeply concerned the United States. Americans were also angered by the Cuban government’s seizure of American property worth hundreds of millions of dollars. The United States government retaliated first by putting an embargo on Cuban sugar and later by shutting off most exports to that island. Ill feeling was heightened in the spring of 1961 when a small force of Cuban refugees, with encouragement from the United States, launched a poorly planned invasion that failed to overthrow Castro.

The American republics sought ways to check Communist expansion. The United States was not the only country disturbed by events in Cuba. The Castro revolution doubtless had an appeal for poverty stricken people in other Latin American states and Communist military aid provided Castro with a more powerful army than most neighbouring states. In 1960, a meeting of the foreign ministers of countries belonging to the OAS took place at San José, Costa Rica. A declaration was issued warning Soviet Russia against interfering in the Americas.

The Alliance for Progress provides a co-operative approach to improving ways of living. To improve conditions in Latin America, the United States proposed the Alliance for Progress in the early 1960’s. The underlying purpose of the Alliance is to encourage each country to draft a program for national development. The United States stood ready to contribute 20 billion dollars in economic aid over a ten-year period, but there was an equal need to attract private capital. Government aid did little good unless wealthy people were also willing to invest funds in a nation’s business and industry. The need for much greater productivity was evident from the fact that in Latin America as a whole, population was increasing more rapidly than the total of the national incomes.

Problems vary from country to country, but among the basic reforms needed were a check on inflation, more equitable taxes and more efficient tax collection, better education and more efficient land use. To finance such projects as low-income housing, land reclamation and hydroelectric power, an Inter-American Development Bank was established with a capital of just over 800 million dollars. Half of this sum was put up by the United States and the rest by Latin American countries. The present capital of this Bank was in excess of two billion dollars and some 200 development loans totaling about one billion dollars have been granted by it.

In brief, as the split between the free nations and the Communist world deepened, the United States led the way in building the defenses of the free world. Through alliances and other co-operative efforts, American leaders hoped to “contain” Russia and prevent Communist aggression.

3. What did the postwar future hold?

The study of world history gives us a glimpse of the world today and the forces which have helped to shape it. To understand how all this came about, we have to study the record of man’s past struggles and achievements, uut what of the future? What will the world of tomorrow be like? The person who would attempt to foretell the future is bold indeed, but it raises questions which will shed some light on the kind of world in which we will live. One question is: How are science and technology (the practical application of science to industry) remaking our world?

Science and technology were pushing ahead at breakneck speed. Never before had man faced the prospects of such rapid change in his way of life and in the extent of his knowledge. This rapid change was made possible by the growth of science and technology. A few illustrations of the then recent advances pointed to the promise of the future.

1. Power. “Splitting the atom” was one of the greatest achievements in history, but ever since atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, mankind lived in the terrifying shadow of their destructive power. There were, however, advances in the use of atomic energy for peaceful purposes. Several countries, including the United States, built atomic power stations to generate electricity for homes and factories.

Especially striking has been the success of the United States in adapting atomic energy to modern transportation. The Nautilus, first of a series of nuclear powered submarines, made its maiden voyage in 1955. In 1960 another nuclear submarine, the Triton, made a beneath-the-surface voyage around the world in 84 days. The Triton traveled 41,000 miles, following much the same route as Magellan’s men nearly 450 years before.

Late in 1961, the Enterprise, an American nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, was put to sea. Its atomic fuel enables this ship to cruise 400,000 miles without refueling. By the end of 1962 the navy had its first nuclear-powered cruiser (the Long Beach) and destroyer (the Bainbridge). In that same year, the world’s first nuclear-powered merchant ship, the Savannah, made its maiden voyage.

Even as atomic energy was opening the way to the world of tomorrow, scientists were exploring still more revolutionary sources of power. British and American scientists reported progress in harnessing the destructive force of the hydrogen bomb — much more powerful than the atomic bomb. Scientists are also working on the possibility of drawing energy from the tides and the sun.

2. Knowledge of our universe. While scientists were unlocking the secrets of the tiny atom, they also probed the mysteries of the universe. Aided by more powerful equipment, astronomers acquired new knowledge of heavenly bodies. Huge rockets, based on those used in World War 2, hurtled mankind into the Space Age.

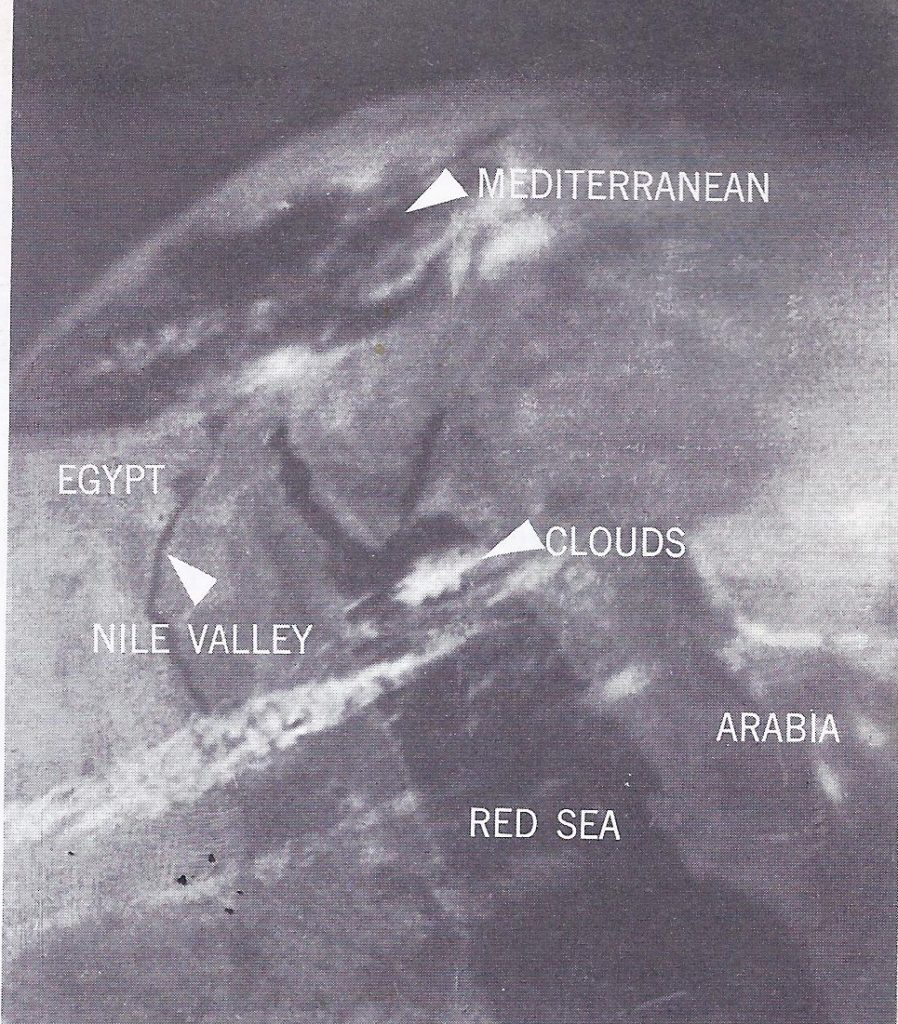

On October 4, 1957, Soviet scientists fired a rocket to launch a metal globe into orbit around the earth. The globe was named Sputnik, the Russian word for “satellite.” Then, early in 1958, the first American space satellite, Explorer I, began its swift journey around the world. Scientific instruments in the satellites recorded information which was automatically relayed to earth by radio.

Following these pioneer events, both the United States and Soviet Russia probed outer space to the moon and beyond. Soviet Russia sent up three Luniks, one of which photographed the far side of the moon. Another hit the moon; a third orbited round the sun. In 1964 American space experts succeeded in crash-landing Ranger VII on the moon. Before impact, television equipment aboard the spacecraft sent back to earth the first close-up photographs of the moon’s surface.

The United States took an early lead in launching new kinds of satellites that could be of great value to all the world’s people. The Tiros and Nimbus satellites photographed the earth’s cloud and weather conditions, thus permitting more accurate weather forecasting. The Transit satellites broadcast radio signals which could help ships and planes navigate in bad weather.

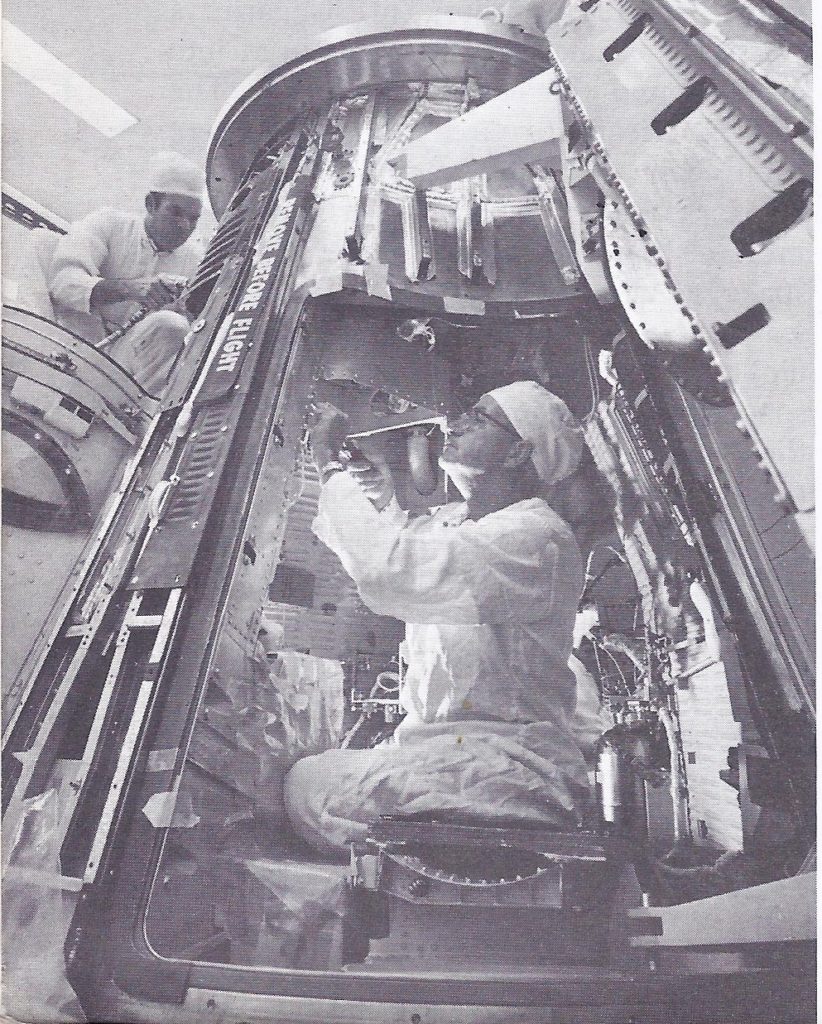

3. Men in space. The launching of satellites led to the sending of men into space. In 1961, Major Yuri Gagarin, a Russian, became the first man to go into orbit around the earth and return. The first Americans to circle the earth were John Glenn, Scott Carpenter and Walter Schirra, each of whom made orbital flights in 1962. The completion of 22 orbits in space by Astronaut Gordon Cooper in 1963 was the last phase of the so-called Mercury flights. The next step in America’s spaceflight program was the orbiting of the two-man Gemini spacecraft. The ultimate goal was to place men on the moon and eventually perhaps other planets.

Meanwhile, Soviet Cosmonauts also made a number of successful flights. In 1963 one Cosmonaut circled the earth for almost five days. On the third day of his flight, the world’s first woman space pilot was also sent into orbit. The two landed in the Soviet Union within a few hours of each other. Then, in the fall of 1964, the Russians orbited a spacecraft which carried three men.

While Soviet space flights generally were carried out under conditions of secrecy, American space probes were conducted in the full glare of publicity.

4. Transportation and communication. New marvels in transportation and communication were everywhere. Lightweight trains, more efficient automobiles, and jet-propelled planes that travelled faster than sound were only forerunners of travel at even greater speed and comfort. One of the most striking advances in communication since World War 2 was the profusion of television. There were now over 60 million television sets in use in the United States alone. Originally devoted largely to entertainment, television now was presenting more programs on public affairs and was being widely used in schools.

In 1960, the United States launched Echo, an aluminum-coated balloon, into orbit 1000 miles above the earth. Scientists predicted that television and radio programs could be bounced off Echo and thus broadcast instantly round the world. Long-distance telecasts were later actually made possible by the Telstar and Syncom satellites.

5. Technology. More and more of the world’s work was being done by machines. Not only were more machines in use but they became much more complicated. Machines with so-called “mechanical brains” were doing jobs hitherto done only by human beings. So important was this trend that many experts say we entered a second Industrial Revolution, one that is based on automation, as the technology of automatic controls is called. So far, the effects of advancing technology were felt chiefly in highly industrialized countries. As automation spreads, the demand for more skilled workers increases. There was a growing need to re-train workers whose jobs were taken over by machines.

6. Health. Scientists and doctors continued to win victories against disease. A significant drop in the number of polio cases resulted from the use of new vaccines. New surgical techniques and new treatments were developed. Doctors were also learning more and more about such deadly killers as cancer and heart disease.

Radioactive materials produced by the atomic era greatly aided medical research and treatment, but they could also be dangerous to human beings. During the postwar years, the United States, Soviet Russia and Great Britain exploded a number of atomic and hydrogen bombs. These test explosions spread radioactive dust in the upper atmosphere. Fall-out was the name given to the radioactive particles which drift back to earth. Scientists differ on the effect the present amount of fall-out may have on living things. They agree, however, that the less radioactive fall-out there is, the better for this and future generations.

What of tomorrow? The problem of fall-out leads to a second important question faced by humanity — will man so conduct himself as to realize the promises of a brighter future? This question has been emphasized by the continuing development of awesome weapon systems.

The rocket power which boosts new satellites into space has also been adapted to military uses. Both the Soviet Union and the United States have continued to perfect long-range missiles. The Polaris missile, armed with a nuclear warhead, can be fired from United States submarines while under water. Triton’s voyage and the success of the Polaris missile meant that nuclear warfare now could be waged from submerged submarines anywhere in the world. Meanwhile, scientists in the United States and Soviet Russia sought to perfect anti-missile missiles to destroy rockets in flight.

The answer to the question concerning man’s future conduct was not clear. Man had not yet progressed as far in his dealings with his fellow man as he has in unlocking the secrets of nature. For proof of this fact we need only glance at conditions around the world during the very years when science made such startling advances.

The free world continued the search for peace. For a brief period during the 1950’s, world tension relaxed. Joseph Stalin, the man who had ruled Russia with a grip of steel for 30 years, died in 1953. A power struggle followed, from which Nikita Khrushchev emerged as top man. In 1958 Khrushchev became prime minister of the Soviet Union.

The West tried to find out if the new Soviet leader was sincerely interested in peace. In 1953 President Eisenhower called upon the Communist world to end the cold war in Europe and the hot war in Asia. After months of wrangling, a Korean truce was arranged. In that same year, President Eisenhower proposed that the nations of the world contribute atomic materials and information to an international pool for research in the peaceful uses of atomic energy. Finally, in the summer of 1955 a “summit” conference involving President Eisenhower and the prime ministers of the Soviet Union, Britain and France was held at Geneva, Switzerland.

The Russians shifted their approach in foreign affairs. The Geneva conference provided no swift settlement of points at issue between the Soviet Union and the Western powers. The Russians continued to oppose the unification of Germany and to block practical steps to world disarmament. Even so, world tension relaxed.

A growing exchange of visitors and goods between the Communist countries and the rest of the world began. Khrushchev himself made “good will” visits to Britain, India, the United States and other parts of the free world.

What was the new Russian policy? The free world wondered what had brought about this apparent softening of Soviet policy. Was it real? Partly, of course, the change reflected differences between Stalin, increasingly suspicious in his old age and the more flexible Khrushchev. Partly, it reflected a recognition of the fact that nuclear war would be disastrous for both sides. Partly, it was a concession to the Soviet people, eager for a higher standard of living.

Most of all, the Soviet policy was a shift in method. The Russian Communists recognized that they could not impose their system on countries beyond the reach of their armies. Might it not be better to offer economic aid to the new Countries in Asia and Africa and thus win their friendship? Later they could be converted to communism by one means or another. So reasoned the Communists.

Those who had hoped for a fundamental change in Soviet policy were doomed to disappointment. The Communist states, though termed “people’s democracies,” remained dictatorships. Freedom of speech and of the press existed only to a very limited extent. Rebellion broke out in Hungary in 1956. Freedom fighters seized Budapest, the capital, compelling the Hungarian Communist government to take a stand against Russian domination, but Russian tanks soon crushed the revolt and restored dictatorship. By 1961, the flight of anti-Communists from East Germany to West Berlin and freedom had become so serious a drain on man power that the Communists erected a wall and strung barbed wire to “seal” this escape route.

Crises punctuate American-Soviet relations in the 1960’s. Any assessment of American-Soviet relations had to take into account setbacks as well as gains. Despite occasional periods of relaxation, the 1960’s saw a series of crises in the cold war.

(1) In 1960 Khrushchev opposed sending a UN peace force to the Congo and called for the resignation of UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold.

(2) In that same year Khrushchev torpedoed a summit meeting in Paris, giving as his reason the flight of an American reconnaissance airplane over Russia.

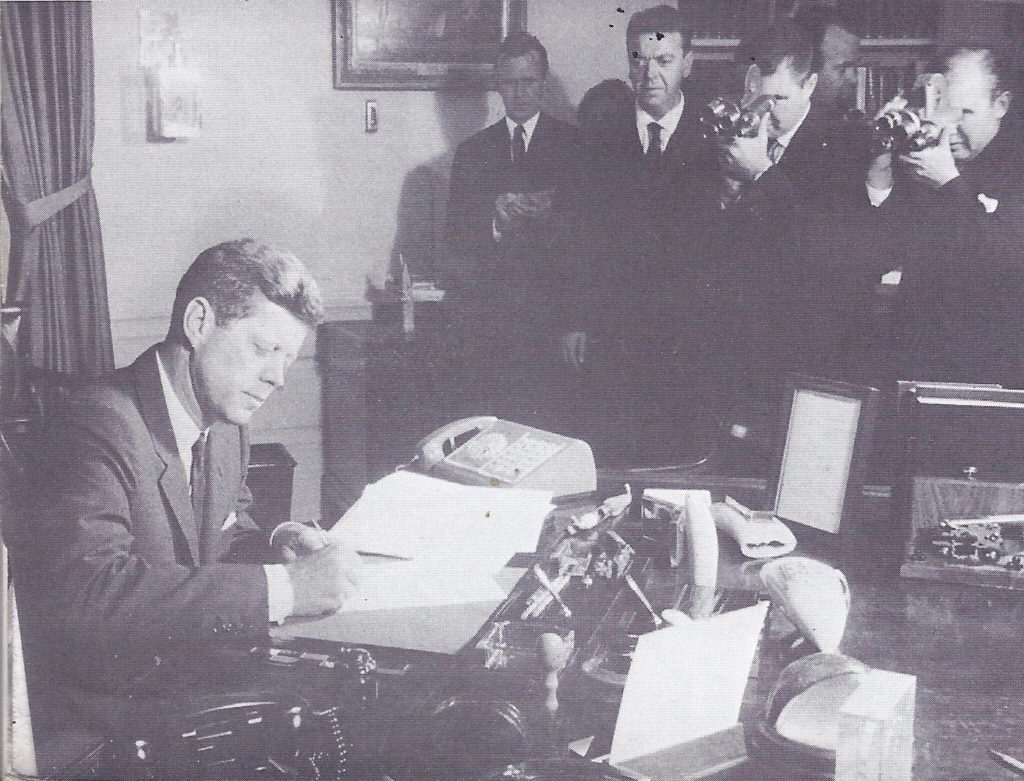

(3) A year later, in Vienna, President Kennedy had a frank exchange of views with the Soviet premier, but no agreements were reached on the control of nuclear armaments, divided Berlin, or other major points at issue. In fact, Khrushchev’s attitude became so menacing in the summer of 1961 that President Kennedy ordered reinforcements to West Berlin and launched a long-term build-up of United States armed forces.

(4) Following an unofficial suspension for three years, the Soviet Union resumed the testing of nuclear weapons in the fall of 1961. The United States then carried out a series of tests the next year.

(5) In the fall of 1962, American reconnaissance airplanes established the fact that Soviet military experts were readying launching sites in Cuba capable of directing nuclear missiles at vital targets in the Western Hemisphere.

Kennedy calls a halt to the military build-up in Cuba. For several uneasy days in October the world stood on the brink of nuclear war. President Kennedy declared a quarantine on the shipment of “offensive military equipment” to Cuba and Russian ships turned back rather than try to run the American naval blockade. The President also demanded the dismantling of the missile bases. Over a period of months all but defensive missiles were returned to Russia and Soviet rocket experts were withdrawn.

The OAS takes steps to check communism in Latin America. The reduction of the missile danger from Cuba did not end the Communist threat in Latin America. Communist intrigue extended outward from embassies and consulates maintained by Communist countries in the Latin American nations. It involveed Communists regardless of nationality and sought recruits among the oppressed and poverty-stricken. In recent years, secret agents, saboteurs, guerrilla specialists, arms and explosives were beING exported from Cuba to other Latin American countries. The Communists hopeD to spread terror and confusion prior to a take-over.

In the summer of 1964 the Inter-American Conference of Foreign Ministers met in Washington to consider what action to take against the Castro regime because of its continued efforts to overthrow the Venezuelan government. Venezuela favoured a resolution calling for all members of the Organization of American States to break diplomatic and trade relations with Cuba. United States Secretary of State Dean Rusk urged the Latin American republics to slap sanctions on Cuba. He also warned the Castro regime that the governments of the Americas “will no longer tolerate its efforts to export revolution through the classic Communist techniques of terror, guerrilla warfare and the infiltration of arms and subversive agents.”

The Rio Treaty of 1947 provided for the use of both sanctions and armed force in repelling aggression, but in the 1964 meeting only the question of imposing sanctions was considered. The foreign ministers agreed to adopt the Venezuelan resolution isolating Cuba except for trade or travel necessary for humanitarian reasons. By the fall of 1964, Mexico was the only one of the Latin American republics that still maintained diplomatic and commercial relations with the Castro regime.

The Soviet back-down in Cuba had important results. The Cuban crisis showed that the United States would not be bullied and that the Soviet Union had no wish to provoke nuclear war. This conclusion was reached both in the free world and in the Communist lands. As a result, Communist China denounced the Soviet policy as “appeasement” and the rift which had already developed between the two countries widened further. Khrushchev before his removal from office in October, 1964, supported the view that the Communist Party in each country should be free to build communism in whatever way best met its own situation. This was a decided change from Stalin’s unyielding domination of satellite countries. In consequence, a tendency appeared in Poland and Hungary and even in Romania to relax controls, to give more thought to a better life for people generally and even to question economic policies advocated by the Soviet Union.

A fest-ban treaty is signed. Less than a year after the Cuban missile crisis, the nuclear powers reached agreement on a partial ban of nuclear tests. The United States, the Soviet Union and Great Britain agreed to suspend test explosions in the air and under water but not underground. The test-ban treaty was regarded by many as a step forward in easing cold-war tensions. Meanwhile, other problems continued to divide the free world and the Communist countries. One of these, Red China’s determination to achieve nuclear capability, was underscored by the first Chinese atomic explosion in October, 1964.

Red China makes trouble for friends and foes. Communist China has followed an aggressive policy in the Far East. The participation of Communist Chinese “volunteers” prolonged the Korean War. China then blocked the unification of Korea and Vietnam as well. Furthermore, Communist China repeatedly threatened to seize the island of Formosa held by Chiang Kai-shek and the Chinese Nationalists. Having taken over the mountain kingdom of Tibet, the Chinese Reds displayed shocking brutality in suppressing a revolt that broke out in 1959. Later that year and again in the 1960’s, Chinese forces began to push into India at points where Red China refused to accept the established boundary.

There were clashes between the Chinese and Soviets along their common frontiers. The Chinese were fiercely competing with the Russians for the leadership of world communism. Chinese agents were active in Latin America, Africa and Southeast Asia. The Chinese leaders point out to peoples in the developing countries that they have more to learn from the experiences of China because the Soviet Union is no longer a “have not” nation and, moreover, belongs to the “white man’s” world.

There are two major reasons for the differences between the two leading Communist nations:

(1) The Chinese Communists clung to the belief, earlier held by Russian Communists, that war with the capitalist world is inevitable and that the outcome will be a Communist victory. The Soviet Union now professed to believe in “peaceful coexistence” (or economic competition) with capitalist countries. It claimed that within a generation it will outproduce the United States and thus prove the “superiority” of the Communist system.

(2) China’s expansionist policies were closely watched by the USSR, which was reluctant to have China become “too powerful too soon.” This attitude probably explains the Soviet Union’s failure to provide more aid for China’s lagging industrial program or to share with the Chinese its “know-how” in the field of nuclear armaments.

In spite of their differences, the Soviet Union and Red China had in common one goal — the expansion of communism wherever possible. The pursuit of this goal had been made abundantly clear by Red China’s policy in Southeast Asia.

What is the future of Southeast Asia? Vietnam was divided into two states in 1954. One of these, North Vietnam, was a Communist state headed by Ho Chi Minh. The other new nation, South Vietnam, became independent but was threatened by Communist aggression from the north. In addition, South Vietnam faced other difficult problems: (1) 900,000 refugees who had left North Vietnam to escape Communist rule, (2) a government paralyzed by eight years of war and lacking adequate revenue and (3) pockets of its own territory held by Communists.

Hopes for the survival of South Vietnam were not high, hence President Eisenhower offered the new republic economic aid. Conditions improved markedly. By 1960 per capita food production in the south was 20 per cent higher than in 1956; in the north it was 10 percent lower. This achievement convinced Ho Chi Minh that he must “liberate the South from the atrocious rule of the U.S. imperialists and their henchmen.” To the Communists “liberation” meant sabotage, terror and assassination. Unable to contain Communist aggression, South Vietnam asked President Kennedy for American advisers, arms and increased economic aid.

Since 1962 the Communist guerrillas had greatly expanded their campaign of terror and subversion, which had been directed and supported from North Vietnam. Specialists and secret agents continued to infiltrate South Vietnam from the north and by way of Laos and Cambodia. Most of their weapons come from Communist China.

Meanwhile, political crises in South Vietnam resulted in two changes of government within a few months. Co-operation between central and local units of government was disrupted. Morale suffered and the Communist guerrillas redoubled their efforts. To some 20,000 guerrillas from North Vietnam were added some 60,000 “irregulars” recruited from the South Vietnamese. Although the people of South Vietnam prefered freedom to Communist domination, they were reluctant to take a firm stand and thus risk Communist retaliation.

To prevent a Communist take-over, American military personnel in South Vietnam has been increased. American crews have piloted military helicopters in missions against the Communist guerrillas, and South Vietnamese pilots have bombed Communist supply routes.

In August, 1964, tension increased when North Vietnamese PT boats launched torpedo attacks against United States destroyers in international waters off the coast of North Vietnam. In retaliation American carrier-based aircraft not only attacked the aggressive PT boats but bombed their bases. President Johnson requested and obtained from Congress a resolution endorsing his policies of helping countries threatened by Communist aggression and of armed retaliation when American forces were attacked. In the words of the American President, the resolution proved “our determination to defend our forces, to prevent aggression and to work firmly and steadily for peace and security in the area.”

The United Nations continues its peacemaking efforts. Following the death of Dag Hammarskjold in 1961, U Thant, a Burmese diplomat, became UN Secretary General. Meanwhile, the membership of the United Nations (currently over 110) had changed significantly. The balance of voting power in the General Assembly now lay in the hands of the new African and Asian nations. Some of these states were sympathetic to the Communist viewpoint, but the majority were uncommitted to either side in the cold war. Though a number of members were still behind in paying their share of UN expenses, daily expenditures were reduced after withdrawal of the UN force from the Congo, but the UN’s financial situation remained critical.

War threatens in Cyprus. Early in 1964, the UN once again sent a peace force to a trouble spot. This time the trouble area was Cyprus, a Mediterranean island 50 miles off the coast of Turkey. Cyprus was a republic and a member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Eighty percent of its people (called Cypriots) are of Greek ancestry; the rest are Turkish. Suspicion and hatred have long existed between the two groups. When Britain agreed to independence for Cyprus in 1960, the new constitution provided that Britain, Turkey and Greece could intervene in the island’s affairs when necessary. The constitution also granted the Turkish minority veto power over legislation and a certain proportion of political offices. There was discontent from the beginning. The Greeks claimed that the Turks had too large a role in the government; the Turks protested that they were being denied their rights.

The UN military force which was sent to restore order was given little authority and enjoyed little success. Concerned lest the Cyprus crisis lead to war between two members of NATO, both Britain and the United States made approaches to the prime ministers of Turkey and Greece as well as to leaders of the opposing factions. In August, 1964, after bombings by Turkish aircraft of Greek Cypriot positions, both Turkey and Greece asked for a meeting of the UN Security Council to consider the problem. Later both countries agreed to a cease-fire. The future of the strife-torn island — and the implications of the crisis for NATO remained in doubt.

These years were largely devoted to the problems of our modern world, but every challenge was also an opportunity. Science placed in our hands powers unknown and even unimagined by the people of past ages. How did we use these awesome powers? Did we build a higher civilization than man has ever been known? Or will nuclear devastation thrust the world into a “dark age”? These questions emphasize the fact that we are living in one of the most exciting and interesting periods of all history.