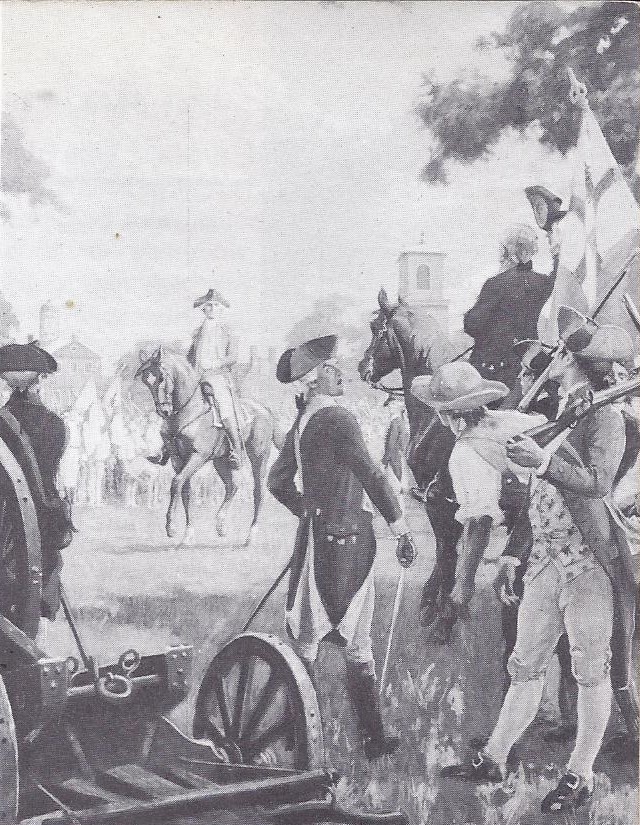

Even though you are familiar with the story of the American Revolution, perhaps you do not realize that only nine short days at Christmas time in 1776 changed the course of the English colonies’ fight for freedom. Within that short space of time, General Washington’s ragged, dwindling army captured the hired German troops at Trenton, New Jersey and routed a British force at nearby Princeton.

To win such surprising victories and to keep the American Revolution from collapsing took the devoted leadership and military skill of General George Washington. It took patriot soldiers whose term of service had run out but who fought on, though they were poorly clothed, halfstarved and ill. In short, the struggle for independence continued because there were men who saw beyond the cold, hunger, danger and weariness of war.

Wherever freedom is won, there are able leaders, men of courage and devotion. Turn, for example, to South America in the year 1819, In a mountain hut General Simon Bolivar, one of the great leaders in the struggle of the Spanish-American colonies for independence, huddled with his staff officers over a candlelit map. Ahead of Bolivar rose the towering cloud-covered summits of the Andes. Somewhere in the valleys beyond were the Spanish troops that Bolivar had to defeat. Quickly he decided to make use of a high, windy, fiercely cold mountain pass. No Spaniard would look for a force of 2100 men from that direction!

Up, up climbed Bolivar’s forces. Trees grew stunted and bent. Wind buffeted and snow blinded the men and horses. Some dropped from exhaustion; others slipped and vanished into the fog-filled canyons. What was left of Bolivar’s army crept down the other side. Not a single cavalry horse had survived and abandoned cannon, like snow-covered mileposts, marked Bolivar’s route.

The exhausted forces were not prepared to strike at the Spaniards, but Bolivar had no choice. To retreat was impossible. A surprise attack on a body of Spanish cavalry gained precious time to rest his men and to gather needed horses. Then Bolivar met and defeated the main Spanish force at Boyaca.

The battles at Trenton and Princeton in North America and Boyaca in South America were not final victories. More battles had to be fought before the English colonists won their independence from Great Britain and before the Spanish colonies could win their freedom from Spain. Here we learn why these two struggles for independence began and how they were won. You will find, too, that a little later the people of Canada won a large measure of self-government without resorting to war. Finally, you will learn what progress was made by the peoples of these three areas — the United States, Latin America and Canada — up to the 1850’s. This story of how the peoples of the Americas won a greater degree of control over their own affairs will be told under these headings:

1. How did the English colonies win dependence and establish a new republic?

2. How did Latin American countries gain their independence?

3. How did Canadians achieve self-government?

1. How Did the English Colonies Win Independence and Establish a New Republic?

A French trader visiting the English colonies in the 1760’s became so enthusiastic about them that he settled down as a farmer. Here is what he had to say about the people in the colonies in the years preceding the American Revolution:

What then is the American, this new man? He is either an European or the descendant of an European, hence that strange mixture of blood which you will find in no other country. I could point out to you a family whose grandfather was an Englishman, whose wife was Dutch, whose son married a French woman and whose present four sons have now four wives of different nations. He is an American, who, leaving behind him all his ancient prejudices and manners, receives new ones from the new mode of life he has embraced, the new government he obeys and the new rank he holds. . . . Here individuals of all nations are melted into a new race of men, whose labours and posterity [descendants] caused great changes in the world.

Of course the people in the colonies during the 1760’s hardly thought of themselves as Americans. They considered themselves first and foremost subjects of the British king and secondly, citizens of the colony in which they lived. Yet by this time certain conditions had helped to create the “new race of men” which the French trader referred to as Americans. What were some of these conditions?

Settlers in the English colonies had a keen appreciation of English liberty. The men and women who left English shores for the colonies in North America were thoroughly familiar with basic English rights and privileges. These, as we read earlier, were written down in such documents as Magna Carta, the Petition of Right and the English Bill of Rights. What’s more, many of the settlers, or their fathers and grandfathers before them, had themselves taken part in the long struggle for freedom in England during the 1600’s. Some were Puritans who had been forced to flee from persecution under Charles 1. Others were Cavaliers who found England an unhappy place in which to live after Cromwell became dictator.

All these settlers were familiar with the hard-won principle that Parliament had the right to pass laws, vote taxes and that members of the House of Commons were responsible to the citizens in England who elected them. Although the colonists recognized Parliament’s right to regulate colonial trade, each colonial assembly voted taxes and passed laws affecting its own particular colony. In short, though the settlers considered themselves Englishmen and loyal subjects of the king, they had become used to a large degree of self-government.

English settlers were familiar with Locke’s ideas. In the 1700’s there were many well-educated men living in the colonies. Some of these men were graduates of British universities, while others had attended one of the several colleges already founded in America. Among them were a number of lawyers who understood the fine points of English law as well as did lawyers in England. They had also read John Locke’s writings and believed as he did that the natural law of reason applied to government as well as science. From the viewpoint of Americans, this law of reason limited the power of the king and Parliament over the colonies.

English colonists were influenced by their surroundings. What contributed most, however, to an independent attitude among the colonists was living in a new and faraway hind. English kings, you will remember, took little interest in the early colonies. When the home government did realize the value of colonies, the difficulty of controlling people 3000 miles away became very clear. For example, laws were passed by Parliament stating how colonists should ship goods and with whom they should trade, but it was difficult to enforce these regulations. Even honourable merchants in the colonies felt that they were justified in smuggling goods in defiance of laws which they had had no part in making.

Living in a new land was as important as distance from the mother country. America offered tremendous opportunities to people who had the courage to leave their old homes, but settlers had to endure many hardships and overcome grave dangers to start a new life in the wilderness. This struggle bred in them a feeling of self-reliance, a confidence that they could take care of themselves. Coupled with self-reliance was a new feeling of equality. Differences in birth, wealth and social position which had great influence in Europe seemed unimportant in a country where staying alive depended on one’s skill with an axe or a rifle.

Tighter British control brought bad relations between the colonies and the mother country. Trouble between Great Britain and the colonies really began at the close of the French and Indian War in 1763. At that time King George III and his advisers decided on stricter control of the colonies. From the British point of view there were good reasons for this new policy. The French and Indian War had been very expensive. Why should not the English colonists help to bear the cost of maintaining troops in America? Other European countries managed their colonies as they wished, so why should the British colonies be an exception? But the colonists themselves felt differently. They had helped to win the French and Indian War. Now that French control had been broken in North America, they were confident that they could take care of themselves without the assistance of British “redcoats.”

Various measures adopted by the British angered the colonists. Each measure in the new program of the British government brought protests because it lessened the freedom the colonists had enjoyed.

(l) The king declared the land lying beyond the Appalachians, including the Great Lakes region closed to the colonists. This ruling (the Proclamation of 1763) angered the trappers and frontiersmen who had expected, after the defeat of the French, to be free to move westward.

(2) Parliament set out to enforce half-forgotten laws that regulated and restricted trade between the colonies and other countries. Such a move was a blow to colonial merchants who had been trading freely for years when the laws were not enforced. The merchants objected strongly to the broad powers given to British officials to search their homes and warehouses for smuggled goods. This, they claimed, violated a basic right of Englishmen.

(3) Parliament approved a Stamp Act. This measure, designed to raise funds, required that government revenue stamps be attached to many articles: newspapers, wills, property deeds, business contracts and even playing cards. The Stamp Act aroused violent protests throughout the colonies. The colonists argued that only their own colonial legislatures had the right to levy taxes on activities carried on wholly within the colonies. In a resolution protesting the Stamp Act, the Virginia House of Burgesses declared that “the general assembly of this colony have the only and sole . . . right and power to lay taxes . . . upon the inhabitants of this colony.”

(4) Parliament passed a law stating that colonists must provide housing for troops that were sent to defend the colonies. The Americans did not see why they should pay taxes or house soldiers they neither wanted nor felt they needed.

The Virginia Bill of Rights

Elections of members to serve as representatives of the people in assembly ought to be free. . ..

All power of suspending laws . . . by any authority without consent of the representatives of the people, is injurious to their rights. . . .

In all . . . criminal prosecutions a man hath a right to demand the cause of and nature of his accusation, to be confronted with the accusers and witnesses, to call for evidence in his favour, and to a speedy trial by an impartial jury . . . that no man be deprived of his liberty, except by the law of the land or the judgment of his peers. . . .

Excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted. . ..

The freedom of the press is one of the great bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained. . . .

All men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.

Relations between England and the American colonies grew worse. This program of stricter control was put into effect between 1763 and 1765. During the next ten years, England and its colonies drifted farther apart. Some Englishmen believed that the American colonists were being forced into revolt. Said a member of Parliament, “The boar will surely turn upon the hunter. . . . Nobody will be argued into slavery.” Some Loyalists (colonists who favoured the king’s cause) also issued warnings, but George III and Parliament continued their blundering and meddling. Additional laws were passed which limited the colonists even more.

The colonists showed their resentment toward British policy in different ways. By their speeches and actions, patriot leaders like James Otis, Patrick Henry and Samuel Adams aroused public feeling against the British. Some outbreaks of violence occurred. Persons appointed to carry out the hated stamp tax, for example, were handled roughly. In 1773, citizens of Boston disguised as Indians dumped into the harbour cargoes of tea on which they were expected to pay duty.

On more than one occasion American colonists united to protest acts of the British government. Nine colonies sent delegates to the so called Stamp Act Congress in 1765, to register their protests against the stamp tax. Several years later, when the First Continental Congress assembled in Philadelphia, all the colonies but one were represented. Even more effective than such meetings were the agreements by which American merchants bound themselves not to buy English goods. The British answer to the colonies was only to adopt new measures to restrict or punish them. Firmness, the King declared, was the only attitude to take toward disobedient subjects.

An open break developed between Britain and the colonies. Up to 1775 there had been little talk of independence. Both Loyalists and Patriots believed that there must be ways to protect their rights peaceably without breaking away from England. During 1775 and 1776, however, more and more colonists came to believe in the necessity for independence. One reason for this was the fighting which took place between British soldiers and colonial militia at Concord, Lexington and Bunker Hill. What was the sense, the colonists thought, of talking peace and loyalty when shots were being fired?

Another strong influence for independence was the appearance in January, 1776, of a pamphlet entitled Common Sense. Its writer was Thomas Paine, an Englishman who had recently come to the colonies. Why, asked Paine, should a small island rule a continent? What was the king of England for? Paine answered this second question in these words: “In absolute monarchies the whole weight of business civil and military lies in the king . . . but in countries where he is neither a judge nor a general, as in England, a man would be puzzled to know what is his [the king’s] business.” Paine’s booklet did much to bring about a final break between Great Britain and its American colonies. George Washington said of it, “I find Common Sense is working a powerful change in the minds of men.”

The American colonies declared their independence. Slowly sentiment in favour of independence grew among the colonists. On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, the body then representing the Thirteen Colonies, adopted the Declaration of Independence. The man responsible for the wording of this famous document was Thomas Jefferson. In sharp and vivid phrases Jefferson poured into the Declaration the best thinking of writers of the 1700’s. The opening words of the Declaration express vigorously the ideas of the natural rights of man and the true purpose of government. The Declaration of Independence is not only cherished documents but has had great influence throughout the world.

What factors helped Americans to win the War for Independence? It was one thing to proclaim independence; it was quite a different matter to secure it. At first glance, American chances of success seemed slight. In fact, from 1776 to 1788 the Patriots waged an uphill struggle against the might of Britain’s armies and navy. Three factors, however, contributed to the final success of the Patriots.

1. Geographic advantages. More than 3000 miles of ocean separated the American colonies from England. This distance, together with the fact that the Thirteen Colonies were spread out over a large area, made the moving and supplying of large British armies difficult. Smaller forces of English troops, aided by hired soldiers from Germany and by Loyalist Americans, were able to capture cities and hold limited areas, but Patriot forces could appear suddenly, attack them and then vanish. Surprise attacks like those at Trenton and Princeton, about which we read in the introduction here, continually bewildered the British generals. They did not know where the Americans would strike next. The Patriots were also helped by the fact that they were better acquainted with the lay of the land than were the British.

2. Washington. Without the determined and brilliant leadership of George Washington, commander of the Continental forces, the war might have been lost.

3. French aid. The Patriots benefited from foreign aid, particularly from France. The French king and his ministers had no particular desire to help the rebellious British colonies. The French govemment was very much interested in embarrassing its age-old enemy England. By helping the young United States, France might be able to strike a serious blow at England’s power.

Before taking any steps the French government naturally wanted to be sure that the Americans had a fighting chance. After the Patriot forces won a clear-cut victory at Saratoga, New York, the French signed a treaty of alliance with the Americans in 1778. France provided money, weapons, soldiers and warships. Spain and Holland also furnished some aid. Thus the Revolutionary War was more than a struggle for independence from England. It was in a sense a world war, a continuation of the earlier wars to maintain a balance among European powers.

The struggle for independence was successful. Foreign aid finally tipped the scales in favour of victory. An American force led by Lafayette (a valiant young Frenchman who had joined the Patriot cause) trapped a British army under Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia. Meanwhile a French fleet made it impossible for the British to bring in more troops or supplies by sea. When Washington arrived from New York with another army, the British had no choice but to lay down their arms. With Cornwallis’ surrender in 1781, the War for Independence was practically over.

Victory meant independence for the United States; it also meant great changes in North America. By the Treaty of Paris in 1783 the United States gained control of the land from the Atlantic to the Mississippi and from what is now Maine to Georgia. Spain ruled Florida and the land west of the Mississippi. Great Britain still held Canada.

The Constitution established a strong government. Winning independence from England did not solve all problems for the new American nation. For several years Americans suffered from heavy loss of trade and a business depression. The most serious handicap of all was the lack of a strong national government.

In 1787 a group of men gathered in Philadelphia for an important meeting. For weeks this body discussed and debated and compromised. The result was the Constitution of the United States, the same Constitution lived under today except for amendments which have from time to time been added. The Constitution left many powers to the individual states, but authorized the new central government (1) to levy and collect taxes, (2) to raise and maintain an army and navy, (3) to declare war and make new ties and (4) to regulate trade between states and with foreign nations.

The Declaration of Independence

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute a new government. . . .

The Constitution of the United States

We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquillity, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. . . .

The United States grew in strength. The new government under the Constitution was launched in 1789. George Washington, who had served his countrymen so well during the Revolutionary War, became the first President of the United States. Under Washington and the Presidents who followed him, the young nation solved many of its problems. The first ten Amendments, our Bill of Rights, were added to the Constitution. Finances were placed on a firm foundation, commerce increased and industries sprang up. Pioneers poured in such large numbers into the lands beyond the Appalachians that a number of new states were added. For several years foreign relations were troublesome, since European nations tended to disregard the rights of the young American republic. Disputes with Great Britain finally led to war in 1812. Although the United States won no clearcut victory, the War of 1812 led other nations to treat our country with greater respect.

The Constitutional Bill of Rights

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated. . . .

No person . . . shall be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law. . . .

In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed. . . . Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.

The United States grew in size. Perhaps the most striking change in the United States between 1789 and 1850 was its growth in territory. Had you been born at the close of the American Revolution, the western boundary of your country would have been the Mississippi River. Some sixty years later, perhaps even within your lifetime, that western boundary would have been the Pacific Ocean! Glance at the map and you will discover what each addition of territory was and when it was made.

You will also notice that the largest addition of territory is marked Louisiana. We will read how Napoleon not only rose to power in France but, through his military genius, became master of Europe. It was Napoleon’s ambition to restore France’s colonial empire and in 1801 he forced Spain to hand over Louisiana to France, but two years later he abruptly changed his mind. American officials sounded out the French government on the chances of buying New Orleans, so that western farmers could be assured of free passage of their goods down the Mississippi. Napoleon replied with an offer to sell the entire Louisiana Territory. President Jefferson seized this chance to double the size of the United States in a single peaceful move.

America’s rapid territorial growth had far-reaching consequences. The addition of the vast open spaces in Louisiana and other regions speeded-up the westward movement. The fertile soil of the rolling prairies beckoned to people in the East. Family after family set out by flatboat, steamboat and covered wagon to try their fortunes. “Old America seems to be breaking up and moving westward,” reported one observer about 1820. To these restless easterners was added a constantly growing stream of immigrants from Europe. American pioneers opened up Texas and Oregon to settlement. When gold was discovered in California in 1848, men from all kinds of jobs and backgrounds joined in a wild scramble to “get rich quick.” Many who failed to realize this dream nevertheless settled down as farmers and townspeople in the Far West.

This westward movement bred a strong spirit of equality and democracy. What a man could do, not who he was, seemed the important thing to frontiersmen. As new states were created, the constitutions which they adopted did away with earlier restrictions on voting and holding office. Gradually this tide of democracy spread back to the older states in the East. By the 1850’s, practically all white male adults could vote and other steps had been taken to give the people a greater voice in their government.

2. How Did Latin American Countries Gain Their Independence?

The American Revolution influenced the growth of freedom elsewhere. As an American, you may have thought that our War for Independence was important only in the story of our own country, but man’s desire for freedom knows no boundaries; what happens in one country may change the course of history elsewhere. We have already read how the liberties won by Englishmen and the ideas of Locke were transplanted to the English colonies and helped to bring about the American Revolution. In turn America’s struggle for independence had effects far beyond American boundaries.

The American Revolution, for example, taught the British government a valuable lesson about the treatment of colonies. When trouble arose in Canada in the 1830’s, Britain adopted a wiser policy. In France, the American Revolution stirred young idealists, like Lafayette, who saw in free America a model for improving conditions in their own country. Dissatisfaction with the French king and the privileged groups led to the French Revolution.

Finally, from the American and French Revolutions, leaders in Latin America gained ideas and courage to carry on their fight for independence. It is that story, the story of how the peoples of the Americas controlled by Spain, Portugal and France won their freedom that we shall now consider.

Latin America covers a wide area. Today Latin America contains 20 republics. (See map) In addition to certain islands of the Caribbean Sea, it includes Mexico and Central America, as well as almost all of South America. This area is generally called Latin America because it was settled by Spain, Portugal and France, nations whose languages are derived from the Latin.

Within this immense region which stretches from the Texas border to the southern tip of South America, massive mountain ranges extend north and south. From the mountains great rivers flow east to the Atlantic. There are vast stretches of dense jungle and narrow coastal plains and high inland plateaus. Many of Latin America’s geographical features are on a grand scale. Mount Aconcagua, in the lofty Andes, for example, is the highest mountain in the western hemisphere. The Amazon River is the second longest in the world and carries more water to the sea than any other river. The grassy plains of present-day Argentina resemble in size and productiveness those of Americas own Middle West. Although two-thirds of Latin America lies within the tropics, northern Mexico as well as large sections of Argentina, Chile, Brazil and Uruguay have a temperate climate. The southern tip of South America, on the other hand, has a frigid climate because of its distance south of the equator. Even within the tropical regions, a temperate climate prevails on the high plateaus.

Geography affected the struggle for independence in Latin America. Geographic conditions vary sharply in many parts of Latin America. Much of present-day Mexico, for example, is high land with a dry climate, like the Southwest. Yet along the seacoast and in the south, Mexico’s climate and vegetation are tropical. The six Central American republics are largely tropical, but there are highlands where the climate is mild. Argentina has vast open plains called pampas, great forests and lofty mountains. Chile, occupying a long narrow strip along the Pacific coast, includes a rainless desert, one of the most fertile valleys in the world and islands soaked with moisture.

Such geographic conditions were important in the early days of Latin America. Settlements, though widely scattered over more than an entire continent, existed chiefly where climate and altitude were favourable. Natural barriers like mountains and jungles prevented united action and made military campaigns most difficult. Yet, despite these obstacles, Latin Americans persevered in their struggle for independence. What conditions led them to do so?

The people of Latin America were divided into distinct classes. In colonial times the population of Latin America’s widely scattered settlements fell into five groups. (1) The most privileged were the European-born whites who occupied the highest positions in the government and in the Catholic Church. (All Latin American countries were strongly Catholic.) (2) Next in influence were the descendants of the Europeans who had been born in America. Some of them owned large estates; others were wealthy merchants or mine-owners. Such people, if descended from Spanish or French families, were commonly referred to as Creoles. (3) Many of the early European settlers married Indians. Their descendants, of mixed European and Indian blood, were called mestizos. Most of the mestizos were farmers or craftsmen. (4) A large part of the population in some of the Latin American countries such as Mexico and Peru were pure-blooded Indians who worked on the great estates or in the mines. (5) Especially in the West Indies and in Brazil, there were Negroes who had been brought to America as slaves. One reason why the people of Latin America found it difficult to unite in a common cause was the fact that they were separated into distinct classes.

Spanish civilization influenced most of Latin America. The Spaniards got off to a head start in exploring and settling the New World. For this reason European ways of living were introduced earlier into parts of Latin America that were settled by Spaniards than along the Atlantic seaboard of North America. Visitors to Mexico see churches and cathedrals dating back to the early 1500’s. By 1551, fifty-six years before Englishmen established their first permanent colony in North America, the Spaniards had founded universities in Mexico City and in Lima, Peru. Spanish customs and traditions and the Spanish language are the heritage of most of Latin America. In Brazil the background and language are Portuguese and in Haiti they are French.

The Spanish government maintained strict control over its colonies. Most European countries in the 1500’s and 1600’s, as we already know, were ruled by kings who exercised absolute power over their subjects, at home and in their colonies. Furthermore, the Latin countries Spain, Portugal, and France-believed even more strongly than Britain that colonies existed only for the benefit of the mother country. Nowhere was this truer than in Spain.

By the 1700’s the Spanish empire in America was divided into four provinces, each ruled by a governor or Viceroy who was the king’s representative. The viceroys had military forces and a host of officials to carry out their commands. Most of the government’s policies were planned to benefit the mother country. Shiploads of treasure dug from the gold and silver mines by the Indians were sent back to Spain. Colonial trade was strictly supervised for Spain’s profit. For example, (1) Spanish colonists were seldom allowed to produce anything which was grown or made in Spain; and (2) all goods had to be shipped in Spanish vessels. Trade and industry could not grow naturally under such restrictions.

Dissatisfaction was strongest among the Creoles. Although the peoples of Latin America had lived under European control for nearly 300 years, they did not like it. By the late 1700’s, discontent was increasing rapidly. The Creoles had a particular grievance, for they were barred from important positions in the colonial government. They had little use for the proud gentlemen born and brought up in Spain who lorded it over them.

Liberal ideas stirred Latin Americans. Many Latin Americans, in fact, believed that it was time they were granted a voice in their government. They had read what Locke, Voltaire, Rousseau and others had written about natural rights. They were stirred by the American Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution. They were also aware that Frenchmen had rallied to the cry of “Liberty and Equality” and had overthrown their oppressive royal government. All these happenings aroused hopes of freedom in the hearts of Latin American patriots.

The mother countries naturally tried to prevent the spread of liberal ideas in their colonies. The Spanish government, for example, even forbade Spanish Americans to read or discuss what had happened in the United States and France, but news did find its way into the Spanish colonies, largely by way of Latin Americans who had visited Europe. Many of these patriots –including Francisco Miranda and Simon Bolivar of Venezuela, Bernardo O’Higgins of Chile, José de San Martin of Argentina –l aid plans for throwing off European rule.

Events in Europe gave latin Americans their chance. In 1808 Napoleon conquered Spain and placed his brother on the Spanish throne. The Spanish colonies owed no loyalty to this upstart king. Furthermore, the British fleet controlled the Atlantic Ocean. The colonies, therefore, were free from any real control by Spain. Patriots in various Spanish colonies seized this opportunity to start revolts and proclaim their independence.

Some of these movements were successful. In other places the uprisings were put down by Spanish colonial officials. After 1814 the flame of revolt was fanned to white heat. Napoleon had been defeated and the rightful king of Spain returned to power. Instead of offering the colonies greater freedom in trade and government, the Spanish king tried to restore the old system of control and sent troops to recapture the areas in rebellion. Having had a taste of freedom and a chance to trade freely, Spanish American patriots were in no mood to accept these conditions. One by one, various parts of the Spanish colonial empire in the Americas fought for independence. Throughout Latin America, as in our own country, much credit for victory belongs to certain outstanding leaders.

Haiti had already won independence from France. Even before the movement for independence got under way in the Spanish colonies, the spirit of revolt had successfully flamed forth against the French in Haiti. You will remember that Columbus had visited the island of Hispaniola in the West Indies. During the 1600’s and 1700’s the island passed into French hands and became generally known as Haiti. A few hundred rich planters lived in Haiti, but the great majority of its people were Negro slaves.

One of the slaves was Toussaint L’Ouverture. Toussaint had been fortunate enough to obtain an education and had read the writings of men like Voltaire and Rousseau. Under his leadership a revolution broke out among the Negro slaves in 1794. Within a few years victory over the French seemed to have been won. Slavery was abolished and a constitution was drawn up. Then Napoleon, who dreamed of re-establishing France’s colonial empire, sent an army to Haiti. Although the French did not reconquer the island, they captured Toussaint and sent him in chains to France, where he died in prison. Cruel fighting and savage destruction followed until the French troops were forced to leave in 1804 and Haiti became a Negro republic.

Order was restored by another former slave, Henri Christophe. Christophe established schools and developed a tax system that put Haiti on a sound financial basis, but he compelled people to work on great building projects, including an imposing palace for himself as “Emperor.” This they resented. Finally, discontent grew into revolt and Christophe killed himself to escape capture. Meanwhile the independence movement was sweeping the Spanish colonies.

Father Hidalgo started the revolt in Mexico. In Mexico City’s National Palace there hangs a simple church bell. To Mexicans it is their “Liberty Bell,” for on a September night in 1810 Father Hidalgo, a village priest, rang that bell in his little church. The clanging bell summoned the poor Indian and mestizo farmers to strike a blow for freedom.

Father Hidalgo’s plan failed, for he was neither a general nor a statesman. His poorly armed and ill-trained rebel army, though 80,000 strong, had little chance against disciplined Spanish troops. Father Hidalgo was soon captured and shot. Another priest, Father Morelos, who tried to carry on Hidalgo’s program, met the same fate. Neither Hidalgo nor Morelos received assistance from well-to-do people in Mexico because the landowners had little interest in a struggle to relieve the condition of poor farmers. Nevertheless these two priests, troubled by the misery of their peaple, had started a movement which later was to achieve success.

Mexico finally won its independence but not democracy. New leaders arose in Mexico and the Creoles increasingly took over the revolution. In 1821 a revolutionary army seized Mexico City and proclaimed Mexico’s independence, but independence did not bring freedom for the rank and file of Mexicans. One revolutionary leader actually got himself proclaimed “Emperor.” Although he was soon ousted and a republic was set up with a President and Congress, Mexico made little progress toward self-government. Often the strongest leader, with soldiers to enforce his commands, controlled Mexican affairs. One such leader was Santa Anna. For many years, as President of Mexico and even when out of office, Santa Anna influenced Mexico’s history.

Miranda started a revolution in Venezuela. Just a year after Father Hidalgo’s bell called Mexicans to revolt, Venezuela (to use its present name) proclaimed its independence from Spain. The leader of this movement was Francisco Miranda, who had spent years working to further the cause of liberty. Although Miranda aroused the spirit of revolt in Venezuela, his success was short-lived. Following a severe earthquake in the principal city, Caracas, Miranda’s revolt collapsed.

Bolivar took up the fight to free Venezuela and Colombia. The fact that Venezuelans finally won their independence was due largely to Simon Bolivar. Bolivar, who came from a wealthy Creole family, won many supporters to the cause of freedom. At first he had little success against the strong Spanish forces in Venezuela. So Bolivar decided to invade neighbouring Colombia, where there were fewer Spanish troops. (Together Venezuela and Colombia at that time formed a large part of the vice-royalty of New Granada.) To accomplish this purpose, Bolivar and his men made the daring march over the Andes described at the beginning. Bolivar then returned to Venezuela and defeated the Spanish there. His efforts freed both Venezuela and Colombia.

San Martin led revolutionary forces in Argentina, Chile and Peru. To the south, another great leader was winning victories. San Martin, a native of what is now Argentina, gained valuable experience while in the Spanish army. Later he had a part in the freeing of Argentina. In 1810 the people of Buenos Aires, then as now the leading city in the southern part of South America, had forced the Spanish Viceroy to flee and had set up their own government. Six years later came Argentina’s declaration of independence from Spain, but Argentina was not yet a closely knit nation.

San Martin realized that Argentina’s independence was threatened as long as the Spanish had forces in present-day Chile and Peru. So San Martin developed a long-term plan. The first step was to train an army in western Argentina. The next step was to free Chile by uniting this army with the forces of Bernardo O’Higgins, the Chilean patriot. To do this San Martin would have to lead his army across one of the highest parts of the Andes — an even more daring exploit than that of Bolivar. The third step was to create a small navy and attack Peru by sea as well as by land. Due in large part to San Martin’s leadership, the plan worked. Chile was freed and in 1821 San Martin entered the city of Lima and proclaimed the independence of Peru.

Bolivar completed the freeing of South America. Although the Spanish had withdrawn from Lima, they still had strong forces in Peru. Both Bolivar and San Martin knew that these forces must be overcome. The two leaders held a secret meeting but could not agree on future plans. Realizing that the two armies should be combined if freedom were to be won, San Martin gave up his command and returned to Argentina. With the enlarged revolutionary forces under his command, Bolivar won a decisive victory over the Spaniards in 1824. This assured the independence not only of Peru but of all Spanish South America.

Brazil won its independence peacefully. In the meantime an odd situation had developed in Brazil, which belonged to Portugal. Shortly before Napoleon dethroned the Spanish king in 1808, he had sent French troops into Portugal. The Portuguese king then fled to Brazil. For a time, therefore, the government of Portugal was located in this colony rather than in the mother country.

After Napoleon’s fall from power, the king of Portugal returned to Lisbon, leaving his son, Prince Pedro, to govern Brazil. In 1821 Pedro declared Brazil’s independence from Portugal. He and his son ruled Brazil as emperors until 1889, when it became a republic.

The Monroe Doctrine declared “Hands Off America!” Although Spain had lost nearly all its possessions in the Americas early in the 1820’s, it still eyed them greedily. France seemed willing to help them regain its colonies, but expected to be rewarded by receiving a share of them. The British, however, opposed any such arrangement, since it would injure the valuable trade Great Britain had built up with the new Latin American republics. Great Britain therefore suggested that the United States join it in a policy of keeping European nations out of the Americas. The powerful British navy could be used to back up such a policy.

Americans naturally sympathized with the Latin Americans in their struggle for freedom. The United States government had recognized the independence of several Latin American republics. Our government and the British government were agreed that no European army ought to be sent to the Americas, but Spain’s plan to reconquer its American colonies was not the only threat to the United States. Russians were moving southward along the Pacific coast from Alaska. Since President Monroe and his advisers expected Great Britain to back up this country anyhow, they decided to have the United States act alone.

In a famous message President Monroe in 1823 declared that “the American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers. . . .” The United States, said Monroe, would not meddle in the affairs of Europe; on the other hand, any interference with existing governments in this hemisphere would be considered evidence “of an unfriendly attitude toward the United States.” In the face of Monroe’s statement (called the Monroe Doctrine) and Great Britain’s sea power, Spain abandoned the hope of regaining its lost colonies. A serious threat to Latin America’s independence had been removed.

Bolivar was unable to achieve all his dreams. Bolivar, who had earned the title of “Liberator,” had looked far beyond mere independence from Spain. He hoped that the new Latin American nations would become republics in which the people would enjoy personal rights and share in the government. He also dreamed of binding the nations of Latin America together in a close union. As early as 1824 he had called a conference of the free Latin American countries in Panama. Wrote Bolivar, “The one objective which holds me in America … is the Panama Congress. If I succeed with it, good; if not, I lose all further hope of being useful to my country. . . . Without this federation . . . I see civil war and disorder flying from country to country.”

Many years passed before either of Bolivar’s dreams was realized. Most of the Latin American countries drew up constitutions and set up republics, but the mass of people, as in Mexico, gained little share in government. In most countries, too, one dictator after another rose to power. Revolutions and wars were frequent. Nor were Bolivar’s hopes realized for uniting the Latin American nations. Only a few Latin American states sent delegates to the Panama Congress and the conference failed to produce lasting results. There was no further serious attempt at inter-American conferences until 1889, when the United States invited all Latin American countries to send delegates to Washington to discuss common problems.

Independence did not bring democratic government. Latin America’s greatest problem after winning independence was lack of stable democratic government. As we have read, most Latin American states were republics in name only. They were ruled by caudillos, a Latin American term for political or military leaders. The caudillo might be legally elected president; but once in office and backed by the army, he often did away with elections or controlled the outcome and became a dictator. Rival caudillos often opposed one another, so there were many revolutions. These, however, usually resulted in nothing more than a change in dictators, for revolutions interfered little with the day-to-day lives of the people. For many years and to most Latin Americans, “independence” meant no more than the exchange of Spanish rule for caudillo rule.

Latin Americans were not prepared for self-government. Why did Latin Americans put up with dictators? One answer is that they did not have the experience in self-government which English settlers enjoyed in what is now the United States. These English settlers understood that liberty meant freedom but with regard for the rights of others. To them patriotism meant loyalty to a government in which they had some part and justice to these English settlers and those who mingled with them meant the right to speedy and public trial in open court. According to Bolivar himself, Latin Americans of a hundred or more years ago did not have any such understanding of the foundation stones of national self-government. He said that many Latin Americans thought freedom meant the right to do just as they pleased when they pleased; that they had no understanding of national loyalty; and that to them “justice means vengeance.”

We must remember that Latin Americans had grown accustomed to being ruled from above during the generations they had been under Spanish control. As a result, they saw nothing unusual in rule by dictators. You did as you were told and tried to keep out of trouble. You left government to the few men interested in it. If these men promised to maintain law and order and did so, you were satisfied; if they failed, others would take over the government.

We will read about the progress of Latin America in more recent times. Meanwhile let us see how Canada, another area in the Americas, achieved self-government.

3. How Did Canadians Achieve Self-Government?

Canada, as you will recall, originally had been settled by the French. The descendants of the French settlers lived in the lower St. Lawrence Valley, a region sometimes referred to as Lower Canada. They spoke French and had French laws and customs. In religion, they were Roman Catholics. Imagine their fears, therefore, when Canada passed into the hands of Protestant England in 1763 at the close of the French and Indian War. Would England attempt to change their language, customs and religion? Would it change their form of government?

French Canadians kept their religion, laws and customs. In 1763 England’s king issued a Royal Proclamation whose provisions pleased French Canadians because of its promise of religious freedom. Eleven years later Parliament passed the so-called Quebec Act. This law (1) gave Canadian Catholics complete religious freedom, (2) allowed French Canadians to retain their old laws and customs and (3) extended westward the lands open to them. The Quebec Act seems to have satisfied the French Canadians, for they refused in 1775 to side with the American forces invading Canada. Throughout the American Revolution they were loyal to England.

English Canadians demanded change. During and after our War for Independence, many Loyalists left the United States and went to Canada. They settled in large numbers in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and north of Lakes Ontario and Erie. In the early 1800’s many Englishmen came to Canada. The region of the upper St. Lawrence grew rapidly and came to be called Upper Canada.

The settlers in Upper Canada were for the most part Protestants who were opposed to the terms of the Quebec Act. To their way of thinking, it not only favoured French Canadian Catholics but stood in the way of real self-government. Loyalists also resented the fact that in the new country they lacked many privileges and rights which they formerly had had in the Thirteen Colonies. They demanded changes.

Change brought conflict and deadlock. In 1791 Parliament acted to still the clamour from Upper Canada for self-government. Upper and Lower Canada were divided into separate provinces. Each had its royal governor and a law-making body consisting of a council and an assembly. Members of the council, or upper house, were chosen by the governor, who also could veto acts passed by the elected assembly, but the plan did not work smoothly. In both Upper and Lower Canada governors and their councils often were in disagreement with the elected assemblies. There were frequent deadlocks over tax questions, religious matters and the appointment of government officials.

Canadians wanted responsible government. Both the English-speaking people in Upper Canada and the French Canadians of Lower Canada, then, were dissatisfied. The people of Upper Canada wanted greater control of their own affairs. Also, there was widespread objection in Upper Canada to the concentration of so much power in the hands of a few wealthy and influential families. The French Canadians of Lower Canada wanted continued assurance that they would be permitted to keep their language and customs. They too resented the fact that real control of the government rested not with the elective assembly but with the governor and his council.

People in both Upper and Lower Canada wanted a government of their own choosing which would be responsible to the people. In other words, they wanted the heads of the political party that won an election to be the real heads of the government, as they are in Canada and England today. After small-scale revolts broke out in 1837, Parliament sent Lord Durham to Canada to draw up a plan to solve Canada’s political problems.

The Durham Report paved the way for responsible government. Lord Durham was an able and open-minded Englishman. He was determined that England should not lose Canada as it had lost the Thirteen Colonies. Lord Durham reported that Canadians ought to be given responsible government. At first England’s Parliament was unwilling to go so far. It united Upper and Lower Canada under a single government. There was to be a single legislature of two houses, but the council, as before, was chosen by the royal governor. Seats in the elective assembly were divided equally between Upper and Lower Canada.

By 1850 the Canadians had won the responsible government they wanted. A new royal governor, Lord Elgin, began the practice of choosing members of the victorious political party for his legislative council. Canadians, through their legislature, gained control of all their affairs except the making of war and peace.

The years from 1775 to 1850, then, saw the peoples of the Americas make great strides toward winning control over their own affairs. The people of the United States gained independence and established a democratic nation; Latin America won independence but not democracy; Canada achieved self-government without independence. Here was striking proof that the Americas were, indeed, a New World.