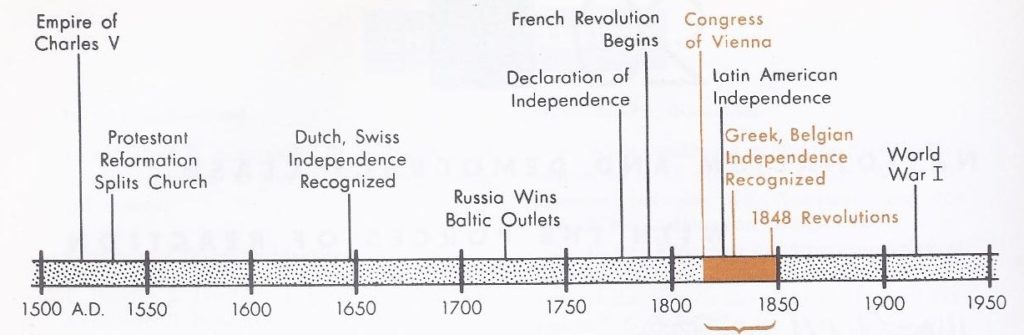

The Austrian city of Vienna in 1814 would have dazzled even a Hollywood director. Emperors and empresses, kings and queens, dukes and duchesses — members of ruling families who hoped to recover thrones or to increase their lands — were there. So were leading statesmen from practically every country in Europe. For the so-called Congress of Vienna was meeting to make peace, now that Napoleon had finally been defeated. The Congress was going to set the world right again.

The old city was overcrowded. Hotel rates soared and homeowners rented their houses at unheard of prices. Laundresses grew wealthy and tailors prospered, silks and gold lace were everywhere. The highborn visitors found little time for sleep because of the never ending round of festivities. There were dinners and parties, receptions and dances, operas, ballets and concerts led by the great composer and orchestra leader Beethoven.

So the rulers and aristocrats wined and danced, bowed and flirted. Vienna merry go round might have been a good term for the great international peace conference in 1814. You should not get the idea that there were no serious minded people present at the Congress of Vienna. There were and they knew what they wanted. While most of the visitors were caught up in the social whirl, these statesmen took time to confer on serious matters. Their purpose was to stamp out the ideas of liberty and equality and of self government proclaimed during the French Revolution and spread by Napoleon’s armies.

Could the members of the Congress of Vienna smother these ideas? One might as well ask whether they could stop winds from blowing or check the flow of rivers fed by countless small streams. Here we read how old and new ideas clashed and will answer these questions:

1. How did the Napoleonic Era affect Europe?

2. How did rulers and statesmen try to turn back the clock?

3. What progress did nationalism and democracy make between 1815 and 1850?

1. How Did the Napoleonic Era Affect Europe?

The Napoleonic Wars created difficult problems. Wars always create problems; and the Napoleonic Wars, which were long-drawn-out and turned Europe upside down, were no exception. (1) Napoleon had changed the map of Europe. Should the old boundaries be restored? (2) Napoleon had deprived many a ruler of powers which he and his family had long held. Should these powers be given back? (3) Napoleon had replaced some rulers with others of his own choosing. Should the ousted rulers get back their crowns?

The backward-looking peacemakers at Vienna in 1814 generally had but one answer to all three questions, “Yes.”

The Napoleonic Wars had aroused new hopes among conquered people. It was easier to talk about restoring kings and princes and giving them their former powers than to do it. Napoleon’s wars had deeply affected the peoples of Europe. Wherever Napoleon’s conquering armies went, new governments were set up which gave or promised reforms and an end to unjust laws. Wherever French armies went, they spread the ideas of the Declaration of the Rights of Man. What was to be done about these reforms and these notions of liberty and equality? The peacemakers at Vienna might oppose liberty and self-government, but would the people themselves willingly forget such visions of greater freedom? Moreover, as we read earlier, the Napoleonic Wars had aroused a new spirit of national patriotism among the peoples of Europe. Could such feelings be quickly uprooted?

National feeling had been weak before Napoleon’s time. Always, of course, people have been loyal to something. Even primitive savages are loyal to their families or tribes. Both in ancient Greece and in Italy during the Middle Ages people were loyal to their cities. On the medieval manors people gave support to the lords from whom they received protection. When Europe became divided into kingdoms, people transferred their loyalty to their king or emperor. In the 1700’s, however, people in most countries thought of themselves as loyal subjects of a government, not as a people bound together by common ties.

The people of the German states had little basis for national feeling. The lack of any strong feeling of unity, “or oneness,” was clearly evident, for example, among the people of the German states. When Napoleon first fought these states, he faced armies made up of trained and disciplined soldiers. Fighting was carried on by men who made a career of soldiering, while the rest of the people went on with their farming and trading as if the wars about them were not their concern. Their crops, livestock and buildings might be destroyed, but they replanted and rebuilt just as their fathers and grandfathers had before them.

As a matter of fact, to what could people within the various German states be loyal? There was no strong central government. For centuries the Holy Roman Empire had been little more than a name. Each of the many small German states was governed by a prince or other nobleman who had no interest in Germany as a whole. Austria and Prussia were the only powerful German-speaking states and each looked out for itself. You can see, then, that there was little to encourage a feeling of patriotism among all Germans.

The Napoleonic Wars aroused German patriotism. After a few years of fighting against Napoleon’s armies and living under the control of the French, however, the viewpoint of people in Prussia, Bavaria, Saxony, Hanover and other German states changed. They began to feel that they were all Germans and that they had a common enemy, the French.

The Prussians took the lead in developing this new national patriotism among the German states. Baron Stein, a Prussian statesman, worked to free Prussian serfs. Patriots, he declared, could not be made out of serfs. General Schamhorst, a Prussian general, copied the idea of universal military training which had swelled the victorious armies of the French Revolution and Napoleon. Under Scharnhorst’s plan the Prussian army became a sort of military school for all the young men of Prussia. Each man, after he was trained, was discharged and returned to civilian life while another man took his place in the army. In this way a strong military reserve force grew up and the Prussian army, which Napoleon had destroyed, was rebuilt into one of the strongest in Europe.

There were other leaders in this up surge of German national feeling. There were great teachers and thinkers, and poets like Ernst Arndt, whose fiery pamphlets and songs bade Germans rise and band together against their common enemy France. There were martyrs to patriotism, like the humble innkeeper Andreas Hofer, who led his Austrian mountaineers through winding passes to attack the French. In the end, Hofer was captured and put to death, but a people who could produce such men, though defeated for a time, could not be kept down forever.

National patriotism appeared in other countries. What happened in Germany is an example of what was going on else where in Europe during Napoleon’s wars. National patriotism flamed high in Spain among the guerrillas (a Spanish name for soldiers fighting a “little war”) who wore down the French by sudden raids and night attacks. More and more Spaniards joined the guerrillas until Spain had developed a first rate secret or “under ground” fighting force.

The people of the separate states and cities in Italy also began to draw together as a nation. Belgians and Norwegians caught the spirit of national patriotism as did the Poles. We have already read how the Russian people harassed Napoleon’s troops on their disastrous retreat from Moscow. In short, all over Europe groups of people began to feel a spirit of oneness or national unity.

THE GERMAN’S FATHERLAND

by Ernst Arndt

Where is the German’s fatherland?

Is it in Swabia? Is it the Prussian’s land?

Is it where the grape glows on the Rhine?

Where sea gulls skim the Baltic’s brine?

0 no! More great, more grand

Must be the German’s fatherland!

“Wherever resounds the German tongue,

“Wherever its hymns to God are sung. . . .

There is the German’s fatherland,

Where oaths are sworn by clasp of hand,

Where faith and truth beam in the eyes,

And in the heart affection lies. . . ,

Be this the land,

All Germany shall be the land!

National patriotism grew out of several elements. National feeling, however, rests on something much deeper than defense against a common enemy or some serious danger. The things which bind a people together in a feeling of oneness are varied and may differ somewhat from one nation to another. Nevertheless, certain common ties are likely to have a strong influence in developing national feeling or patriotism.

1. Language. Often the people who speak a common language belong to the same national group. There are, of course, exceptions to this rule. The Swiss, for example, speak three languages — German, French and Italian — in different sections of their country, though they think of themselves as one group or nation. The development of national languages did much to divide Europe into separate nations. After the invention of printing had made possible an increasing number of books in the language of the common folk, people began to draw together in certain language groups. Bavarians and Saxons, for example, read the same German books as did the Prussians. South Germans and North Germans discovered they had much in common.

2. Religion. In the 1500’s, we recall, Christians in most of Europe split into two groups, Protestants and Roman Catholics. The Protestants, in turn, split into many smaller groups. Lutherans were strong in northern Germany and Scandinavia. There was the Church of England, the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, the Dutch Reformed Church in Holland. In France, in Spain and in Italy, most people were Catholics. There were, of course, countries like Germany where the people were sharply divided in religious belief; and in most countries there were small groups which did not accept the major faith. In general though, a common religion tended, like a common language, to bind a people together. It had united the Dutch in their fight for independence from Spain. The Poles, who were Roman Catholics, felt themselves doubly oppressed when ruled by Prussians, who were Lutherans and by Russians, who were Greek Orthodox.

3. Common background and interests. Common background and interests were also important in developing national spirit. A people whose history recorded deeds of glory, who could boast great leaders, or who had produced something fine in literature or art, felt a common pride. People who shared common interests were likewise drawn together. Consider, for example, industry and trade. In the Middle-Ages industry and trade had been controlled by the guilds in towns and Cities. As kings gained power, they became interested in promoting trade. Then national governments passed laws that helped trade and commerce. These laws helped to increase the feeling that the nation, as a nation, had certain common economic interests.

National spirit presented a problem to the peacemakers at Vienna. National spirit, then, grew rapidly at the opening of the 1800’s. It was very important in building up resistance among conquered peoples and helped to defeat Napoleon. National patriotism could not be turned on and off at will like a water faucet. Once aroused, it became a force with which the rulers of Europe and the peacemakers at Vienna had to reckon.(1 )

(1 It is true, as we have read, that national spirit inspires people to resist foreign invaders and demand their rights and liberties at home, but translated into an ambition for power and backed by the fearful weapons of modern warfare, nationalism can cause great harm. )

2. How Did Rulers and Statesmen Try to Turn Back the Clock?

In spite of the difficult problems which faced the peacemakers at Vienna, 1814 was a great year for the rulers and nobles of Europe. Napoleon, the little man who had toppled so many of them from power and had ruled most of Europe, was a prisoner on a lonely island. Now kings and nobles had a chance to undo the mischief Napoleon had caused. Now, they said, was the time to put an end to self-rule and to republics and to the “silly ideas” about the rights of man which the French armies had spread. To members of the privileged classes, such ideas brought back the nightmares of the French Reign of Terror — screeching mobs raiding palaces and the swish of the falling guillotine.

Old ideas won temporary victories. As soon as Napoleon was defeated steps were taken in some countries to return to old days and old ways. The King of Spain, now that he had regained his crown, lost no time in putting into effect his own ideas. He tried, as we read to restore the system of strict control over Spain’s colonies in America. He also threw out the Spanish constitution of 1812 and even threatened with death any of his subjects who spoke of reviving it. This constitution, the work of reform-minded Spaniards, had limited the king’s power and abolished serfdom in Spain.

Sometimes the attempt to return to old days was carried to silly extremes. In Germany some rulers set out to restore old army customs. Young army officers were ordered to wear corsets to give them slim waists and improve their appearance in uniform and to wear powdered wigs to give them dignity. In parts of Italy roads were abandoned, bridges broken down and gardens destroyed merely because the French had built them.

Reactionary viewpoints triumphed over liberal ideas. In short, most of Europe’s rulers and their advisers were reactionary. They gathered at Vienna determined to restore conditions to what they had been before the French Revolution and Napoleon had upset Europe and because they were in control of the Congress of Vienna, these reactionary rulers and statesmen paid little attention to liberal ideas — ideas about the rights of man, about limiting governments by means of constitutions and about national patriotism. The common people of Europe had nobody at the Vienna peace table to express their desires.

A small group dominated the Congress of Vienna. The peace conference at Vienna continued until mid-1815. Although it included representatives from practically every country of Europe, scarcely any general meetings were held. Most of the work was done at small conferences and most of the decisions were made by a small group representing the great powers — Austria, Russia, Prussia and Great Britain. The ministers and agents from lesser states were given little opportunity to speak or to offer advice. Instead, they enjoyed themselves at banquets, receptions, dances and the theatre.

The most influential person in the inner circle which controlled the Congress was Prince Metternich of Austria. Metternich was charming and witty, the cleverest diplomat of his day. He earned the nickname of the “coachman of Europe” because his program for peace decided the road Europe was to take. That road, according to Metternich, was absolutely clear — return Europe to the old ways of doing things and give back to kings and nobles their former power. Change and progress, according to Metternich, were dangerous. Democracy, he believed, meant disorder. Metternich was not only certain which road Europe should take; he was equally confident that he was the man to lead the way.

Other members of the inner circle at Vienna were the Czar of Russia, the King of Prussia and Lord Castlereagh, a British statesman. Although these leaders agreed on the need to restore former conditions in Europe, each looked after the special interests of his own country. Bitter disagreements resulted. This bickering gave France’s representative, the shrewd, wily Prince Talleyrand, the chance he needed. When Prussia and Russia demanded more land, Talleyrand promised Austria and Great Britain that France would help them oppose Russia and Prussia. His smooth talk and ability to bargain made it possible for him to work his way into the inner circle.

Defeated France received generous treatment. Talleyrand’s influence helped to win fairly generous treatment for France. The leaders of the Congress had reasons of their own for acting generously toward their defeated foe. Frenchmen had started the trouble over liberty and equality and it would be well not to stir them up again. Moreover, if punished too severely, Frenchmen might be unwilling to accept their restored Bourbon King, Louis XVIII. So France’s boundaries were only pushed back to what they had been in 1792. In addition, France was required to pay a moderate sum for the damage it had caused and to give back the art treasures Napoleon and his generals had seized and sent to France.

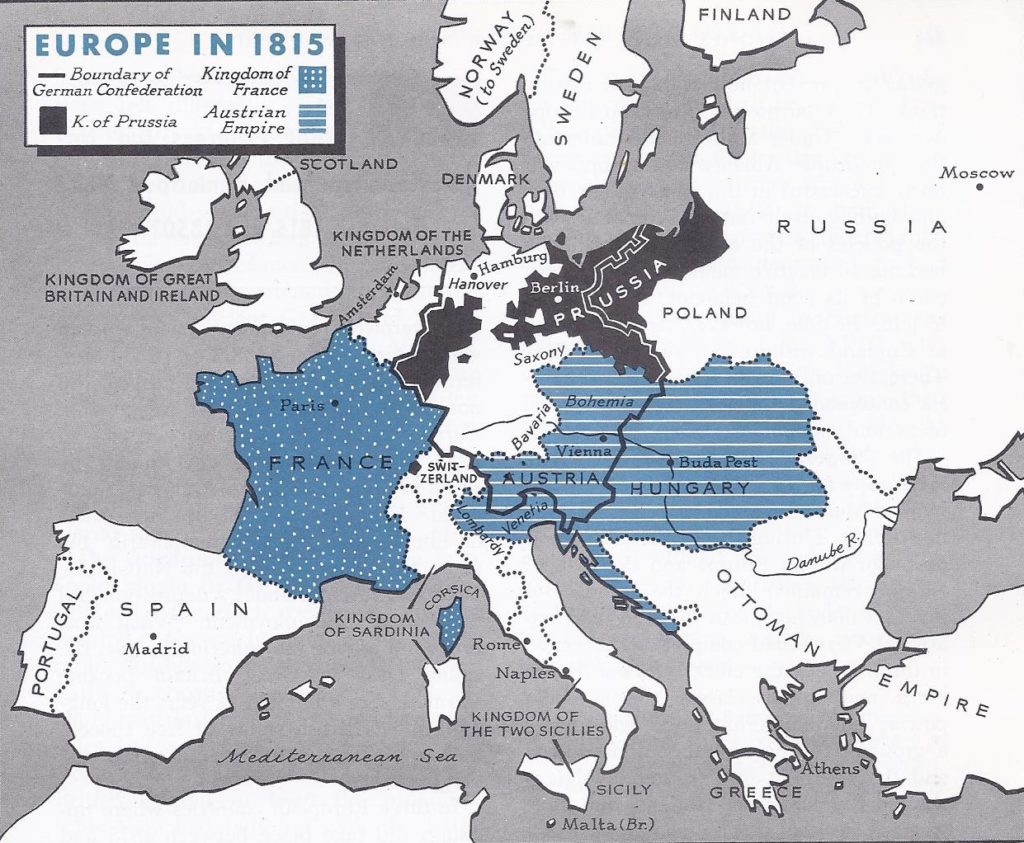

The peacemakers followed certain rules in settling Europe’s problems. If you will compare the two maps showing Europe (1) at the height of Napoleon’s power and (2) at the close of the Congress of Vienna, you will notice striking differences in boundaries and in the ownership of territory. These changes were not accidental. They resulted from certain rules adopted by Metternich and his associates to undo the damage caused by Napoleon’s conquests and to reward the victors. What were these rules and how did they work out?

1. The Congress restored former rulers to their thrones. Besides placing Louis XVIII on the throne of France, the peacemakers restored the former kings of Spain and certain Italian and German states. The return of these monarchs meant a return to power of kings and nobles and a loss of liberty to the people.

2. The Congress erected barriers around France. In order to prevent France from again endangering the peace of Europe, steps were taken to create a ring of stronger states along its border. For this reason, Belgium was joined with Holland and the two countries were merged into a single state. (Great Britain shared in the cost of fortifying the France-Belgium frontier.) Prussia was awarded increased territory along the Rhine. To resist a possible French attack off Italy, the Kingdom of Sardinia was enlarged and the north Italian states of Lombardy and Venetia were handed over to Austria.

3. The Congress awarded new territory to countries to compensate for losses. The leaders of the Congress shuffled the map of Europe around like so many pieces in a jigsaw puzzle. If a country which had fought Napoleon lost territory, this was balanced by land elsewhere.

For example, Austria was given Lombardy and Venetia not only to help encircle France but also to offset the loss of Belgium to Holland. When Russia received most of Poland, Prussia was rewarded with other lands in western Germany. Since control of Finland had passed to Russia, Sweden was given Norway, which had been under Danish rule.

The peace settlements benefited the leaders of the Congress of Vienna. Obviously, these rules favoured the Big Four at Vienna. Austria, Russia and Prussia all got more power and territory. Although Great Britain made no gains in Europe, it held on to certain valuable colonies which its fleets had seized during the Napoleonic Wars. These colonies included the island of Malta in the Mediterranean, Trinidad in the West Indies, Ceylon in the Indian Ocean and Cape Colony at the southern tip of Africa.

The peacemakers paid little attention to the wishes of the people. Europe was rebuilt to suit the whims of kings and statesmen and not according to the wishes of the people. The restoring of former rulers dealt a serious blow to liberals’ hopes for reform. The parceling out of land to this king or that state ignored the rising national patriotism which had helped to defeat Napoleon.

The situation was particularly bad in Italy and Germany. Italy remained divided into many small states. It was, in Metternich’s scornful words, just a “geographic expression”–that is, the name Italy applied to an area, not to a united country. In Germany the Holy Roman Empire with its hundreds of states was not revived, but neither was Germany permitted to become a single nation. Instead, a German Confederation of 38 member states was formed. This loose league of separate states was kept weak by requiring that most actions must be agreed to by all members. Moreover, the German Confederation was under the leadership of Austria. To put it briefly, Metternich strengthened the position of Austria at the expense of unity in both Germany and Italy.

The Congress of Vienna drew up agreements to preserve peace. Peacemakers usually try to prevent future wars as well as to settle the problems of past wars. In the hope of preserving world peace, the League of Nations was created after World War I and the United Nations after World War II. After Napoleon’s wars the Congress of Vienna drew up two agreements to maintain order in Europe. The first, the so-called Holy Alliance, was prepared by the pious but impractical Czar Alexander I of Russia. All rulers, said the Czar, should agree to treat each other as Christians. Most of the rulers of Europe signed the statement to be polite to the Czar, but they did not take seriously this agreement to be guided by “justice, Christian charity and peace.” In fact Metternich called it “a loud-sounding nothing.”

The second agreement was far more effective. This was the Quadruple Alliance between Russia, Prussia, Austria and Great Britain. These four powers, which had fought together to defeat Napoleon, agreed at Vienna to work together to prevent new wars and revolutions. Their purpose was to keep Europe as it was. Under Metternich’s leadership the Quadruple Alliance for a time was fairly successful in this aim. Great Britain, finding itself out of sympathy with the policies of the eastern powers, soon became an inactive member. France, because of its good behaviour, was allowed to join. In time, however, France as well as England withdrew from the alliance. Thereafter only Austria, Russia and Prussia continued their efforts to stifle liberal ideas and national feeling.

The Congress of Vienna set the course for Europe for 35 years. The peace plans worked out at Vienna lasted until the mid-1800’s. During these years there was no major war in Europe and the map of Europe remained much the same. This fact does not mean that the reactionaries at Vienna had completely succeeded in turning back the clock. Outwardly the kings and upper classes continued in power, but simmering underneath were a growing feeling of national patriotism and the yearning for freedom. Belgians wanted freedom from Holland and Norwegians wanted to be completely free of Sweden. Poles, Germans and Italians talked of national unity, each for themselves. Everywhere groups of liberals worked for a chance to put the new ideas of democracy into practice. Metternich and those who agreed with him were kept busy putting out the fires of revolution in one country after another.

3. What Progress Did Nationalism and Democracy Make Between 1815 and 1850?

Metternich’s reactionary system worked well at first. Between 1815 and 1830 Metternich, the “coachman of Europe,” did not have much difficulty in steering Europe along the reactionary road. In most parts of Europe, government by restored kings and upper classes flourished. Even in Great Britain, the cause of liberty was set back temporarily because the heavy costs of the Napoleonic Wars had brought about a depression and widespread unemployment. When riots broke out among the suffering people, the ruling class in Great Britain became alarmed. For a number of years the long established British rights of free speech, free press and free assembly were suspended.

In three European countries where uprisings did take place between 1815 and 1830, Metternich had little trouble in crushing them. In Germany, he frightened the rulers of the German Confederation into adopting rules for dismissing any professor or student who criticized a German government and for censoring newspapers and pamphlets. He sent Austrian soldiers to help the king of the Two Sicilies to crush revolutionists who talked of uniting Italy. He also got France to send troops to Spain to end an uprising against the high-handed king of Spain.

Revolution succeeded in Greece. Not all the revolutionary fires during this period, however, were put out. In Greece the people rose against their masters, the Turks and savage fighting took place. Metternich wanted to ignore the uprising and let the Turks and Greeks fight it out by themselves, but the Russians felt differently. They wanted to help the Greeks because both Greeks and Russians were of the Greek Orthodox faith. They also favoured any movement which would weaken their old rival and enemy, the Ottoman Empire.

Moreover, Englishmen and Frenchmen, whose education was based largely on the literature of ancient Greece and Rome, sympathized with the Greeks. Many of them went as volunteers to help the Greeks. After a long struggle during which they received much help from Russia, France and England, the Greeks won their independence. A constitution was drawn up and a foreign king was placed upon the throne.

The Quadruple Alliance failed to help Spain regain its lost American colonies. Although Metternich was not greatly interested in Greece, he did want the Quadruple Alliance to help Spain recover its Latin American colonies, but Great Britain balked at the idea, for the British wanted to keep the profitable trade they had built up with the Latin American republics. At this time also, the United States announced the Monroe Doctrine. With this stern warning from the United States and with the British fleet barring the way, the Quadruple Alliance gave up its attempt to help Spain regain its last colonies.

By 1830 cracks had appeared in Metternich’s program. What had happened in Greece and Latin America actually made little difference to Europe. Neither uprising seriously upset Metternich’s plan for smothering national feeling and democratic government in Europe. What was important was that (1) Russia, in the case of Greece and (2) Great Britain, in the case of Latin America, had refused to go along with the Quadruple Alliance. The great powers were no longer in complete agreement with Metternich’s ideas.

This fact pointed to more trouble in the future. In the clash between Metternich’s program and the demands of European peoples for greater liberty and national unity, there were two red-letter dates –1830 and 1848. In both these years new revolutionary movements broke out and in both cases they were sparked by an upheaval in France.

Moderate government in France was followed by reaction. Louis XVIII, who became King of France after Napoleon’s defeat, had more common sense than many of his Bourbon relatives. He did not try to make himself an absolute ruler, but agreed to a constitution that made France a limited monarchy. According to the constitution, the king could not make laws without the consent of the French Assembly. Moreover, the best of Napoleon’s reforms — his code of laws, the financial system and the centralized form of government — were kept.

Although Louis’ middle-of-the-road form of government satisfied French businessmen and bankers, there were some French nobles who wished to restore conditions as they had been before the Revolution. The leader of these reactionaries was Charles X (a brother of Louis XVIII), who became King of France in 1824. Charles believed in the divine right of kings. He saw no sense in holding a king’s title unless he possessed full royal power. His boldness alarmed even Metternich.

Frenchmen drove out their autocratic king. Charles X took steps to pay the nobles for the lands they had lost during the French Revolution. This action angered various groups in France. The peasants were fearful — perhaps the next move would be to restore the lands to the nobles. Middle-class Frenchmen were alarmed at the costs of Charles’ land program and feared they might lose the liberties won during the Revolution. When a struggle developed between King and Assembly, Charles ignored the French constitution. He strictly limited voting rights and clamped down on freedom of speech and the press. He also disbanded the French Assembly. These rash acts aroused a storm of protest, and revolt broke out in Paris. In 1830 Charles X was driven from his throne and a new King, Louis Philippe, was chosen.

The spark of revolution fell on Belgium. News of the successful revolt against Charles X of France stirred the hopes of liberals elsewhere in Europe, especially in nearby Belgium. For centuries Belgium had belonged to nearly everyone except the Belgians. It had belonged to Spain; then it had passed to Austria; then it was swallowed up by Napoleon. The Congress of Vienna united Belgium with Holland in order to build a stronger barrier against France Now the Belgians were determined to rule themselves. In 1830, encouraged by the French example, they drove out their Dutch rulers and set up a limited monarchy. The leading European powers not only accepted Belgium’s independence but agreed to protect that little state’s neutrality. This agreement remained unbroken until 1914, when Belgium’s peace was shattered by the tramp of German troops on their way to attack France in World War I.

The Quadruple Alliance failed to prevent Belgium’s independence. The revolution in Belgium upset the arrangements made by the Congress of Vienna. Why, then, were not steps taken to help Holland put it down? The answer is twofold.

First, Great Britain and France were unwilling to lend a hand. Great Britain did not want the troops of a major power in Belgium, and large numbers of Frenchmen sympathized with the Belgians. In fact Great Britain and France actually helped the Belgians to win freedom.

In the second place, in 1830 Austria and Russia were too busy putting down uprisings nearer home. Trouble arose in several states in Germany, and Matternich had to send Austrian troops to Italy to quell uprisings there. The situation in Poland, which was ruled by Russian czars, was more serious. Even though the liberal-minded Czar Alexander had granted the Poles a constitution, they were dissatisfied. They formed secret societies which plotted for independence and when the French people ousted their reactionary king in 1830, the Poles too rose in revolt. For a time they held off the Russian troops, but in the end the rebellion was ruthlessly crushed. The Polish constitution was abolished and hundreds of Polish patriots were put to death or exiled. From then until the end of World War I, Poland was ruled as part of Russia.

By the time order had been restored in Italy, Germany, and Poland, it was too late to do anything about Belgium. So Mettemich and the rulers of Prussia and Russia made the best of a bad situation. After all, they reasoned, the French and Belgian revolutions were not as dangerous as they might have been. Both countries had rapidly settled back into peaceful ways and neither the new French nor the Belgian government threatened foreign wars. The crowned heads of Europe could rest easily again. So they did, until 1848.

Dissatisfaction boiled up again in France. Once again, as in 1830, trouble started in France. Although the Revolution of 1830 in France had got rid of Charles X, it failed to settle anything. France was still split sharply into classes. There were the royalists who wanted a strong monarchy and liberals who wanted a republic. The middle-class businessmen and bankers favoured policies which would make them rich. The workingmen wanted better working conditions and better homes in which to live. The government of Louis Philippe, the new “citizen king,” was a compromise and like many compromises it pleased nobody.

Louis Philippe looked like a democratic middle-class Frenchman. He often stopped to talk with people when he went shopping along the streets of Paris. Underneath, however, Louis Philippe was dull, drab and scheming. He owed his throne chiefly to French businessmen and bankers. Although this group of men made up not more than ten percent of the population of France, it controlled the government because only people with property had the right to vote. Louis Philippe’s chief minister, Guizot, favoured control of the government by the well to do. When people without property complained they did not have the right to vote, Guizot’s answer was, “Then make yourselves rich.”

Frenchmen formed a republic. Finally Guizot went too far. He tried to prevent a rival statesman from holding a political meeting. The Paris mob rose in revolt in 1848 as they had done so often before. King Louis Philippe fled the country and a republic was set up. This was known as the Second Republic, to distinguish it from the Republic set up in France in 1792 during the Revolution.

The Second Republic of France had a stormy history. Times were hard in France in 1848. Many workers were jobless. The question many of them raised was, “What will the new government do for us?” A Frenchman named Louis Blanc thought he had the answer. The government should set up and support “national workshops” to provide jobs for the unemployed.

The government did provide jobs, but not in the way Blanc had planned. Instead of providing different types of work for trained workers, the unemployed were herded together in gangs to build roads and fortifications. This scheme angered the thrifty French farmers. They realized they would have to pay stiff taxes to foot the bill for this kind of unemployment relief. So the government changed its plans. Instead, it offered the unemployed the choice of joining the French army or going hack to their home towns.

The angry crowds of the jobless answered by rioting and building barricades in the streets of Paris. Street fighting raged for three days in June 1848 and thousands of people were killed. Although the outbreak failed, it forecast the end of the Second Republic. The unemployed felt they had been wronged and the well to-do argued that the uprising proved republics to be dangerous experiments.

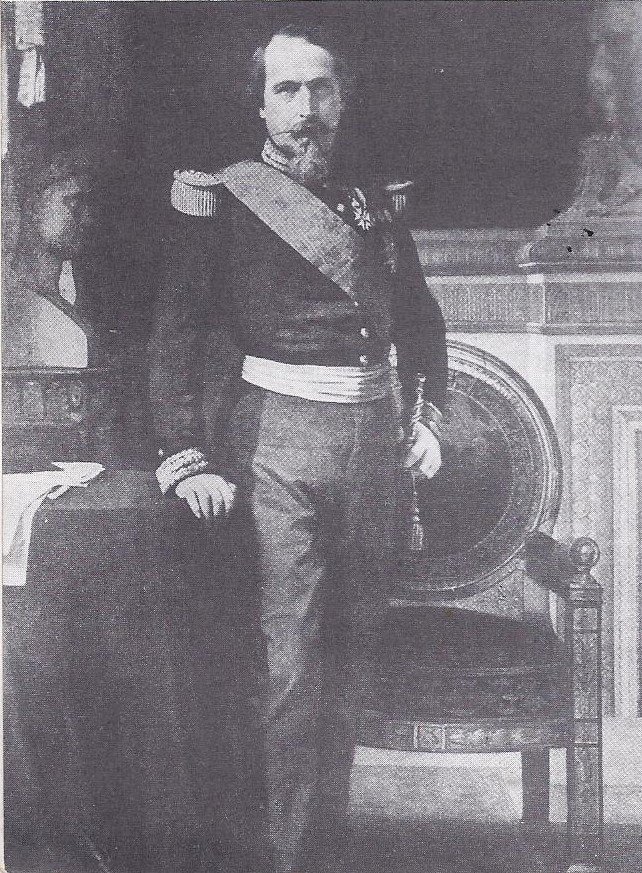

Napoleon’s nephew promised security and order. When the time came to elect a president of the French Republic, a large majority of the voters chose Prince Louis Napoleon, a nephew of the great Napoleon. They supported him for various reasons. Some Frenchmen wanted to revive Napoleon’s empire. Other Frenchmen would have preferred a king of the Bourbon family, but were willing to accept another Napoleon rather than to have a republic controlled by the mob. Still others did not object to a republic but wanted law and order and security for their property.

To all these groups Louis Napoleon offered what he thought they wanted. He promised glory to the soldiers and peace to the peasants. To some he promised to continue the Republic and to others a return to monarchy. What this ambitious man really wanted was power and he got it. First elected president, he made himself dictator in 1851. A year later he took the title of Emperor Napoleon III.

The Revolution of 1848 in France touched off new uprisings. Just as the revolution in France in 1830 had started revolts in other countries, so the uprising in Paris in 1848 set off new explosions elsewhere in Europe. But this time these revolts were more widespread and more serious. Most of them were directed against Austria. People in all parts of Italy joined in a common effort to drive the hated Austrians out of Italy. Non-German people in other areas ruled by Austria — the Hungarians, Bohemians and Poles — also rose in revolt. Each group demanded self rule. In Vienna itself students and workingmen joined together and forced Metternich to flee. For the first time since 1815, the little states in Italy and Germany did not have to obey Metternich’s commands.

Germans attempted national union. Liberal minded Germans took advantage of Austria’s troubles in 1848. They demanded constitutions in many of the separate German states and renewed talk of unifying Germany. A national assembly met in the city of Frankfort to draft a constitution for all Germany. As you might expect, German rulers disapproved of the idea and secretly hoped the Frankfort Assembly would fail. They did not say so for fear of stirring up trouble among their subjects.

The members of the Frankfort Assembly disagreed on many subjects. The chief difficulty arose over Austria: Should it be included in the German union? Austria was a leading German speaking state, but within its boundaries were millions of Slavs, Hungarians and Italians. How could these non-German peoples be included in a truly national Germany?

Plans for German unity failed. At last the Frankfort Assembly decided on a German union without Austria. It offered the rule of this all German union to the Prussian King, but he haughtily refused it with his ideas of the divine right of kings, a crown from an elected assembly seemed like a “crown from the gutter.” In other words, unless his equals, the other German rulers, offered to make him the emperor of all Germany he would have nothing to do with it.

So a chance to bring about German unity failed. Instead, the weak German Confederation was continued. Thousands of disappointed German patriots left Germany for the United States. They brought here a love of freedom which greatly enriched America and was a definite loss to Germany. Among these German patriots was Carl Schurz, who became an outstanding American soldier, newspaperman and United States Senator.

Austria regained control of its empire. Meanwhile the revolt against Austria was being put down. Revolutionary leaders could not agree on what kind of government to set up. Patriots in Italy could not agree on how Italy was to be united. The Austrians took advantage of these disagreements to crush the different rebellions. The Italians were defeated and forced to make peace. The revolts in Bohemia and Poland were also put down. Hungary, however, was a bigger problem. Under the leadership of the fiery patriot Louis Kossuth, Hungary had proclaimed itself an independent republic. It might have succeeded in throwing off Austrian control if the Russian Czar had not stepped in. Caught between Austrian and Russian armies, the Hungarians were defeated and Kossuth fled into exile.

Nationalism and democracy had suffered serious setbacks in 1848. The revolutions of 1848 brought many disappointments.

(1) Attempts to make Germany and Italy unified states had failed.

(2) In all German states but Prussia, efforts to win constitutions had failed.

(3) The hopes for self-rule among the non-German peoples of Austria had been blasted.

(4) Frenchmen enjoyed less freedom under Napoleon III than they had possessed under Louis Philippe.

(5) Metternich was gone, but Austria still dominated Germany and Italy.

(6) Autocrats ruled in Spain, Prussia, Austria and Russia. In all these countries freedom of speech and press was limited. In Russia, Czar Nicholas I had organized secret police to track down and arrest Russians who talked of liberty and equality. Such liberals were executed, imprisoned or sent to Siberia.

However, encouraging progress had been made against the forces of reaction. Yet definite gains had been made between 1815 and 1850.

(1) Serfdom had been abolished in Austria.

(2) The Kingdom of Sardinia in Italy and the Kingdom of Prussia in Germany had been granted constitutions. Though these constitutions still kept power largely in the hands of rulers, they were a step forward.

(3) Belgium had become an independent limited monarchy.

(4) The Dutch had rewritten their constitution so as to give their legislature more power.

(5) Peoples of the Scandinavian countries had gained new popular rights.

(6) Switzerland had obtained a new and more democratic constitution.

(7) As we will read, Great Britain had taken long strides toward government by the people.

(8) Greece and most of Latin America had won independence.

(9) Finally, the Quadruple Alliance, which had started out so boldly to stifle all attempts to change the Vienna peace settlements, had completely fallen apart.

In brief, although the revolutions of 1848 appeared to have been complete failures, nationalism and democracy had made progress in the struggle with the forces of reaction. This progress was slow and painful, but it was real. By 1871, as we will read ahead, Germany was united. So was Italy and Frenchmen had created their Third Republic. In the long sweep of history, what really matters is not whether you win the first battle but whether you win the last.