In 343 B. C., the philosopher Aristotle left the quiet of his study and journeyed to Macedonia, a country in the mountain wilderness north of Greece. He had been hired to tutor the rowdy young son of a king. The boy, Alexander, was a yellow-haired thirteen-year-old. His manners were polite and he seemed to be clever enough, but he was wild. It was hard for him to pay attention to his studies. He much preferred galloping across the fields on his huge horse. He proudly told his new tutor that he had tamed the horse himself. When he did come to his lessons, instead of discussing arithmetic and Greek grammar, he chatted on about armies and his father’s campaigns and his own great plans to conquer the world.

Alexander said he was a descendant of the family of Achilles – his mother had told him so. The Iliad, Achilles’ story, was the one book he loved. He carried it with him wherever he went and read it over and over until he knew it by heart. He dreamed of growing up to be a hero like the ones in Homer’s poem. He pestered Aristotle with questions about Greece and Athens, which he longed to visit. Aristotle said that it was very different from Macedonia.

Philip of Macedon

In those days Macedonia was just beginning to be a kingdom that civilized people talked about seriously. The Greeks still said it was a country of barbarians, but the Greeks called everyone who wasn’t Greek a barbarian. Macedonia was changing. Alexander’s father, King Philip, had spent his youth as a hostage in Greece and he had learned to love almost everything Greek. He had studied the language and tried to learn the ways of the people; but he had also heard the Greeks laugh at the rough peasants of his homeland. When he was set free and went home to become a king, he determined to make Macedonia a country that no one could laugh at again. He turned his peasants into well-trained soldiers and conquered the lands east and west of his kingdom, as far as the Danube and the Hellespont. Then he went back to Greece.

Greece, too, had changed. It was more than fifty years since Sparta had defeated Athens and set itself up as the new “protector” of all Greece. There had been more wars, for Sparta could only do things in its own way and the other cities preferred any way but that one. The council which the Spartans appointed to govern Athens ruled by murder and taxed by robbery. In other places, it was worse. Then the king of Persia picked a quarrel with the Spartans. They fought and the Persians won all the Greek cities in Asia Minor.

That was the signal for the mainland Greeks to try to revolt against Sparta. Thebes, a big city in the north, declared war. Then the Thebans defeated a strong force of the best Spartans, but the sides were so evenly matched that neither could force the other to surrender. Darkness, not victory, ended the fighting. The leaders counted their losses and had no heart to attack again in the morning. They knew that the wars could go on forever. The Greeks would be divided and open to attack from Persia, because no one city was strong enough to hold the others together.

That was the way things were when Philip of Macedonia returned to Greece. He came, he said, as a friend, but his troops were right behind him. He took some land and cities by force, but he also helped the Thebans rescue Delphi and its sacred temples from a band of invaders. For that he won the friendship of the priests and the right to call himself a Greek. Now, wherever Philip went, he spoke of his love for Greece and his fellow Greeks. He said that it was his dream to lead them against the Persians in Asia Minor and he suggested that they might like to join him in a new, strong Greek league.

Demosthenes

To many Greeks, Philip looked like the man who might save them. Others said so because he had paid them to. One of these hired men got up to speak before the Assembly at Athens, hoping to convince the citizens that the king of Macedonia was really a Greek at heart. He told them that Philip was a fine speaker, beautiful to look at and a good companion over a cup of wine. Another speaker, a man named Demosthenes, interrupted him and climbed onto the platform.

“As to these becoming qualities,” Demosthenes began, “I do not see that they add up to a Greek or to a worthy commander. The first, fine speech, becomes any speaker; the second, good looks, becomes a woman; and the third, that King Philip soaks up wine, can be matched by any sponge.”

Nowhere in Greece did Philip have a more determined enemy than this Demosthenes. He was the finest orator in Athens, a city where men spent their lives learning to speak well. In his youth, Demosthenes was not a good speaker. It was said that he trained himself to form words clearly by practising speaking with pebbles in his mouth. He had made his voice strong by reciting verses above the sound of ocean waves. He never ran short of breath, for he had taught himself to speak while he was running or climbing a steep hill. He still practiced in front of a mirror the gestures and movements that held everyone’s attention when he mounted the platform at the Pnyx.

Week after week, Demosthenes used all his talents in a campaign of words against King Philip. He remained the Athenians about the ancient heroes who had fought for Greece. He asked them how they, descendants of such noble men, could welcome this new invader instead of fighting him. It was as difficult for Demosthenes to persuade the citizens of Athens to go to war as it had once been for Nicias to talk them out of it. They listened and cheered – they were very fond of good speeches – but they delayed. They would not vote against Philip, nor would they vote for him.

In 338 B. C., Philip grew tired of waiting and led his soldiers into central Greece. At last the Athenians took Demosthenes’ advice. They joined Thebes in raising as army to stop the invaders. It was a brave defense, but hopeless. Philip’s well-drilled troops were fresh and strong, while the Greeks were worn out from many years of war. The Thebans and Athenians were badly defeated. Demosthenes could speak no more of them. He kept silent while the Greeks, for the first time, swore their obedience to a foreign king.

Philip was full of plans for the great invasion of Persia, but the campaign was never begun. A jealous member of his Macedonian court stabbed him while he was marching, unarmed, in a procession. A day later, he was dead. In Athens the citizens hung themselves with garlands and paraded through the streets chanting hymns of joy. Philip was gone, his son was barely twenty years old and the oaths to obey the king of Macedonia could be forgotten.

Alexander the Great

For two years the Greeks heard little of Alexander. They ignored his laws and made jokes about the little groups of Macedonian soldiers which were still scattered about Greece. When the Thebans attacked the Macedonians in their city, the young king swooped down on Thebes like the god of thunder. He destroyed the city, killed 6,000 of its people and sold the rest into slavery. He left nothing to mark the spot where Thebes had been, except the sacred temples and the house of the poet Pindar. The citizens of the other Greek cities thought again and decided that it was wise not to question Alexander’s youth or his authority.

Alexander’s Campaigns

Aristotle’s pupil had become a handsome and rugged soldier, who looked like the Achilles he longed to be. At twenty, he was already a more skillful general than his father had been and his mind was full of campaign plans. Philip had loved Greece, so much that he wanted all of it. Aristotle had taught Alexander to love the world. For him, Greece was only a beginning.

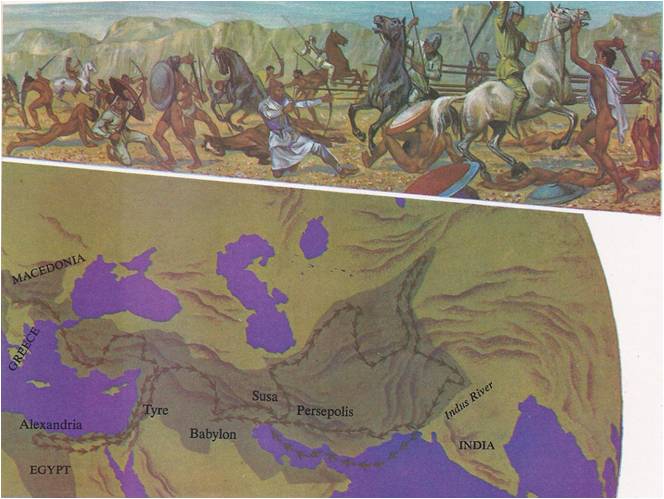

In the spring of 334 B. C., Alexander led a force of 30,000 Macedonian and Greek soldiers and 5,000 cavalrymen across the Hellespont, the channel which divided the western world from the East. Once Xerxes and his Persians had crossed this boundary on the way to invade Greece. Now it was the Greek’s turn and Persia was their goal. On a hill above the Hellespont, at the spot where Troy had stood, Alexander halted his troops. He visited an ancient Greek temple and prayed to Athena to guard his soldiers. He set a crown on the grave of his hero, Achilles. Then he gave the order to march on.

Meanwhile, Darius III, King of Persia, had been warned about the invasion. The number of enemy troops seemed small to him. He laughingly told his advisers that the young Macedonian sounded more impertinent than dangerous. He sent a reliable unit of Persians to stop the invaders at the river Granichus, not far from Troy. He saw no reason to go himself. These little wars were not unusual in his huge empire and he always won them.

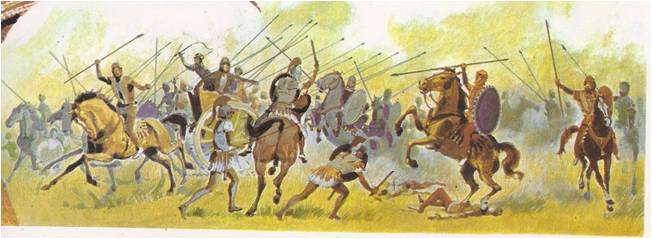

Darius’ soldiers were waiting when Alexander reached the river. They had a strong position and knew that he, like any other commander, would take a day or two to plan his attack. Alexander was not like any other commander. When he saw the enemy line, he gave a shout and led his cavalry across the water in a wild charge that scattered the startled Persians and sent them flying for safety. His foot soldiers waded across to mop up the stragglers and that was the end of the battle.

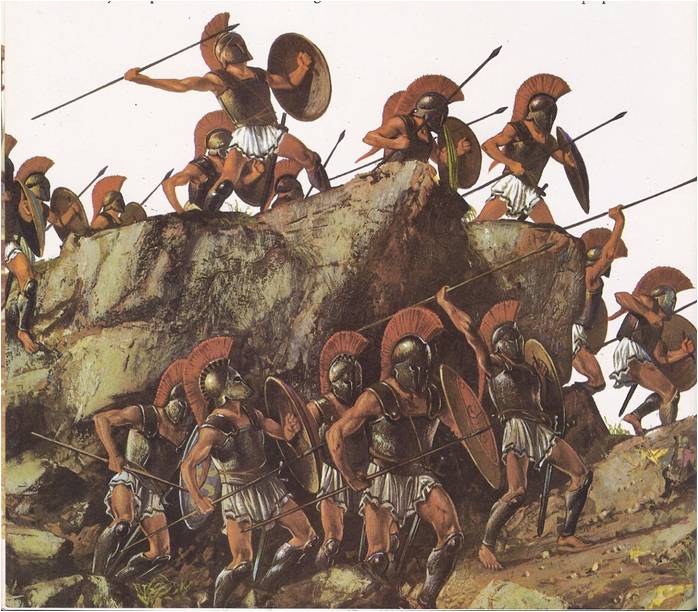

The Macedonian Phalanx

After that, speed was a weapon Alexander used often. He fired his huge troop of cavalry into the centre of enemy lines like a spear and always the enemy soldiers broke in confusion. He was also ready for the tough, close-in fighting, when it was soldier against soldier and the lines of infantry hacked across the field by inches. For that part of the battle Alexander had the famous Macedonia Phalanx. This was a mass of infantry so many lines deep that no enemy charge could break through it. The well-drilled soldiers fought together like a machine. In defense, they made the phalanx a wall without a single gap. In attack, they were a battering ram of men. Alexander had another weapon, one which his enemies could not match – the love and loyalty of his soldiers. He did not send them into battle; he led them and they never failed him.

Darius Flees

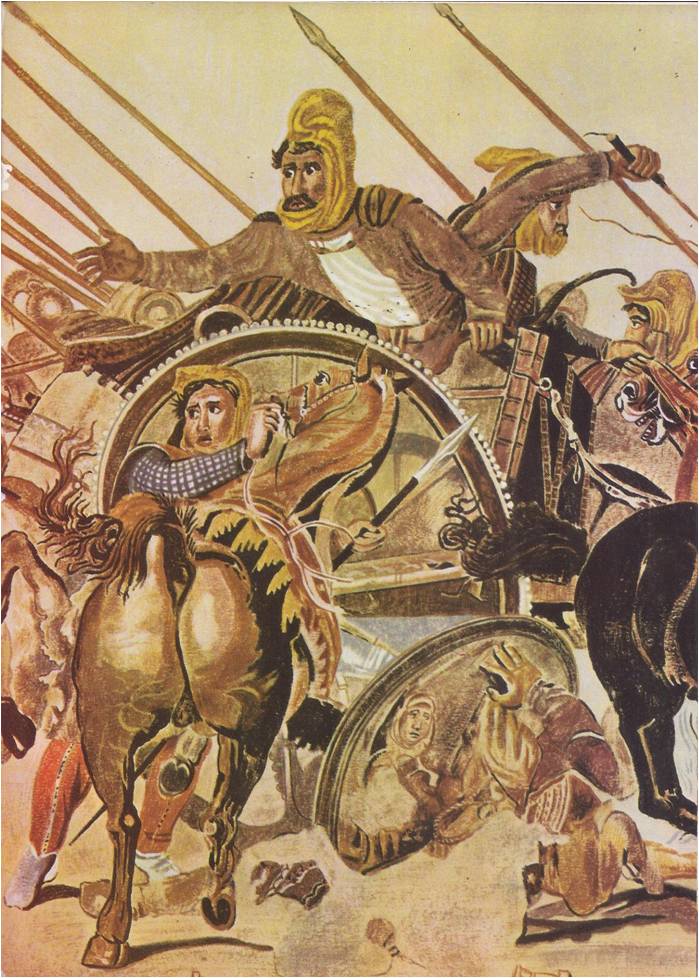

City after city surrendered to Alexander’s soldiers as he took them south through Asia Minor. In less than a year, he had reached Syria. There, at Issus, a narrow plain bounded by mountains and ocean, he came upon the main Persian army. King Darius had come himself, this time, for he intended to smash the invaders once and for all. He stood proudly in his chariot at the centre of the line, surrounded by his hand-picked bodyguard, the finest soldiers in Persia. Alexander aimed his cavalry at the spot. The horsemen thundered across the field and the line splintered. Darius leaped from his chariot, grabbed a horse and rode furiously for safety. His startled soldiers ran in every direction and Alexander’s men were still chasing them at sunset.

That night, the tired visitors made themselves comfortable in the splendid tents and pavilions of Darius’ camp. Alexander moved into the king’s own tent. He bathed himself in a royal bath, with its water pots and ointment boxes all of heavy gold. Then, scented with Persian bath oil, he wandered into the pavilion and found the elegant couches and silver-inlaid tables arranged for a banquet. He sprawled across a cushiony couch, reached for a pear and a cup of wine and sighed: “This, it seems, is royalty.”

Alexander enjoyed being royalty. When he had pushed his way into Egypt, he sailed up the Nile in a gilded barge, nodding to the people who lined the shore and called him “liberator.” At the place where the river meets the Mediterranean, he founded a city and named it for himself, Alexandria. Then he made the long journey across the desert to the temple of Amon, the Egyptian Zeus. There the priests met him, crying, “Welcome, son of Zeus, thy godly father greets thee!”

That made Alexander a god on earth, at least in Egypt. He enjoyed that, too. He began to dress and act more like the Oriental kings, whose subjects knelt to them and called them lord. Some of his old friends were angered to discover that he expected the men who fought by his side in battle to treat him reverently when he sat on his throne. On the field, however, he was the same Alexander who had galloped across the hills of Macedonia. When king Darius made an offer of Peace if Alexander would agree to divide the Eastern world with him, he refused. He left the pleasures of Egypt behind and marched his men back to Syria, determined to take Babylon.

The Battle of Gaugemela

Not long after he had crossed the Euphrates River, his scouts rode in to report a gigantic collection of armies camped on the plain at Gaugemela. Alexander waved his troops to a halt, while he and his generals rode to a hill to survey the enemy camp. Soldiers and equipment covered the plain and the low-lying hills. There were Persian foot soldiers by the thousands, the royal bodyguard, troops from central Asia and the cavalry of a dozen nations. There was also a long line of Persian chariots with sharp blades, like scythes, fastened to their sides. When they charged, the blades would slice through entire files of soldiers.

Alexander returned to his troops. He ordered them to make camp and gave them a day to rest and prepare for the battle. The next night he rode to the hill again. In the flickering light of thousands of campfires he saw the Persians, already arming. One of his generals suggested he attack while it was still dark, to surprise and confuse the enemy. Alexander glared angrily at the man. “I steal no victories,” he said and went back to his camp to wait for the dawn.

In the morning he led his men onto the field at Gaugamela. The wings of the enemy were spread so wide that it seemed they could defeat him just by folding in and trapping his army; but Alexander had put extra guards on the flanks and he hoped that once the fight had begun, some of those far-spread Persian units would have to run to defend the centre. For once, he did not charge; he waited for the enemy to come at him. The first to move were the scythe-chariots, wheeling in from the side, aiming to slice through the ranks. The Macedonian archers peppered them with arrows and grabbed for the horses’ reins as the chariots came nearer. The men in the Phalanxes simply stepped aside, on command and let the chariots rattle past.

Death of Darius

The Persian centre charged, with Darius in the lead. Alexander spotted a gap in the line and rushed his horsemen into it. He turned and beat his way along the line. Now the troops on the Persian wing dashed in to protect the centre. The flying white plume’s on Alexander’s helmet disappeared in the crush of soldiers shields and banners. Suddenly, Darius’ chariot shot out of the tumult. His soldiers gasped when they saw him race from the field and away. The Persian line crumpled, then burst, as the men tried to flee the Macedonian cavalry. Though many of the Asians fought on until dark, the outcome of the battle had been decided when Darius ran. The field at Gaugamela and all of Persia belonged to Alexander.

The gates of Babylon were thrown open for him without a fight. For a time, he made the city his home, living in the royal splendour of the Persian king’s winter palace. Darius himself had disappeared. Alexander tracked him down, only to find that he had been killed by some of his own officers.

The next year, 330 B. C., Alexander set out to conquer and explore the enormous eastern empire which he had won. He roamed across Iran and south through the Indus, followed by a city of tents. His camp was his court and the capital of Persia. Behind the soldiers came officials and clerks, engineers and doctors, money-changers, poets, athletes and jesters. In the evenings, when the camp had been set up, there were races and wrestling, or contests for the musicians. The men chatted over the bowls of wine, as though they were still in Greece or Babylon; but in the morning, they folded up their city and moved on. For five years, Alexander wandered through the strange, half-known countries of his empire. Then his men would go on farther. They had roamed enough and begged him to take them back to Babylon.

The march home took two years more. The caravan made its way along the shore of the Indian Ocean, followed by the fleet which Alexander had built in the Indus. The last stretch of the journey was across a desert wasteland. The water ran out, food was scarce and there were many deaths. At last, the great caravan reached Babylon.

Alexander had learned to love the eastern world, which called him a god. Now, as he began to set his empire in order, he said that it must be both Asian and Greek, an empire in which the nations of East and West shared their best with each other. In his travels he had founded many cities. He had provided the gold for 30,000 Persian youths to be educated in the Greek way and taught the things which he had learned from Aristotle. In his court, he had Persian officials as well as Greeks and Macedonians. He married a Persian princess and insisted that his officers also take oriental wives. A great festival was proclaimed to celebrate the wedding of East and West.

Alexander Dies

Alexander thought about adding Africa and the western Mediterranean to his world. It would take no fewer than a thousand ships of war, he said, and he would build a highway to carry his troops across the top of Africa. Then, in the spring of 323 B. C., he fell sick with a fever. He knew that there would be no more campaigns. He had never spared himself in battle and now the old wounds added to his weakness. He asked that his soldiers be allowed to visit him. As he lay propped up on his couch, the men who had come with him from Greece and Macedonia filed through his chamber. They mumbled their farewells and marched on. A few days later, Alexander died. He was not yet thirty-three and his hair was still yellow, but he would go down in history as Alexander the Great.