In the towns and cities of the provinces, the news of the fall of the Bastille led to wild celebrations and a series of revolts against local governments. These governments had long been unpopular, since most of them were controlled by nobles and others who had bought their government positions from the king. The town people set up new governments, similar to the one in Paris and organized local units of the National Guard.

The revolution spread to the countryside as well. There the peasant uprising had started even before the fall of the Bastille. The peasants made up at least 75 per cent of the population and they had been mistreated and abused by the nobles for many centuries. Due to their poor farming methods and the limited amount of land available to them, these farm people were barely able to support themselves, yet they had been burdened with the heaviest tax load in the country. They paid direct and indirect taxes to the king. They paid the church tax. They also paid various fees and rents to the nobles who owned the land. It was true that many peasants were landowners themselves, but even they had to pay fees to the nobles.

Peasants had to serve in the army and they were required to furnish horses and wagons for the army whenever necessary. They were forced to work on public roads without pay. They were not allowed to hunt or gather wood in the forests. Only the nobles could hunt there — but the nobles could also hunt on lands rented or owned by the peasants. Cattle belonging to the peasants had to be kept at home, but cattle belonging to the nobles could wander about at will over the lands of the peasants, sometimes causing considerable damage. Peasants could seek justice only in courts controlled by the nobles and these courts always favoured the nobles.

These were some of the things the country people complained about and expected the Estates General to do something about. When weeks passed and the Estates General did nothing, the peasants became convinced that the nobles had somehow tricked the “good king” into changing his mind. Many suspected that the representatives they had sent to Versailles might even have been thrown into prison.

The peasants believed the nobles had caused the desperate food shortage by buying up grain and holding it for higher prices. They also believed that the nobles had organized the large bands of beggars that were roaming the countryside. These bands went from farm to farm, threatening to burn farm buildings and to run off the cattle unless they were given food. As spring crops began to ripen in early July, the bands increased in number and invaded the fields to help themselves.

When the peasants heard that the nobles were organizing a large army of beggars beyond the border they rose up in rebellion. They tore away fences that kept their cattle from grazing on the lands of the nobles. Then came news that the Bastille had fallen. There were wild rumours that starving people in the towns were about to march into the country to help themselves to the standing crops and that the approaching army of beggars had been paid by the nobles to slaughter the country people. Thinking that they were fighting for their lives, the frightened peasants armed themselves, gathered in mobs, plundered, burned and destroyed the property of the nobles and the rich.

The local police were helpless. The middle-class people of the towns, unable to protect themselves and their property, called out their units of the National Guard and sent them against the mobs of country people. In the battles that followed‚ hundreds lost their lives.

The Assembly, alarmed at the violence sweeping the country, held a special session on the night of August 4 to take emergency action. “The people are trying to shake off a yoke which has been over their heads for centuries,” explained a nobleman, the duke of Aiguillon. He went on to say that peace could be restored if the privileged classes gave up all their special rights. He then offered to give up all of his rights for the good of the country, but expected to be paid for his property rights. One by one, other nobles rose to follow his example.

A number of decrees were approved to put an end to all traces of serfdom and to wipe out class distinctions. On that night the old order of France came to an end. All Frenchmen were to be equal, subject to the same laws and were to pay their just shares of taxes. All would have an equal chance to serve in the Church, the government or as officers in the army. In addition, Church taxes and dues were to be done away with and the Church was to be reorganized.

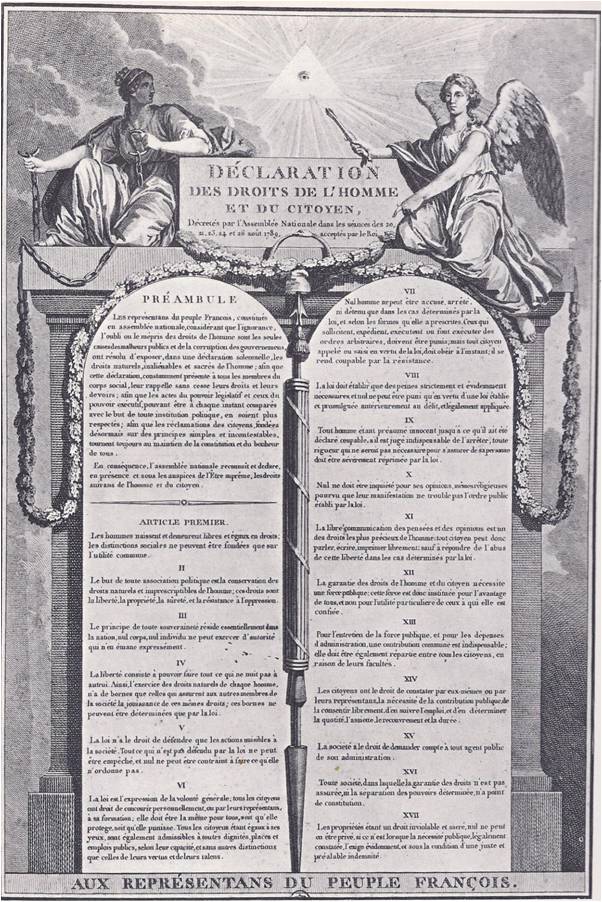

The Assembly was so pleased with its work that it proclaimed Louis XVI “the Restorer of French Liberty.” Next, on August 27, it approved a Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. The Declaration was long and included such ideas as these: All men are born free, remain free and have equal rights. The aim of government is to protect these rights, which are “liberty, property, security,” and the right to fight against unfair treatment. Government is created “not in the interest of those who govern but of those who are governed.” A person is free to do anything that “does not harm another.” He is free to think as he likes and has a right to enjoy freedom of press and freedom of religion. A prisoner is to be considered innocent until proven guilty. All persons are equal in law, in public employment and in taxation.

King Louis did not wish to destroy the privileged classes and therefore he did not approve the decrees of the Declaration. He resisted them simply by doing nothing about them. The Assembly hardly knew what action to take next. Did it have the right to pass laws without the king’s approval? After lengthy debates on the king’s veto rights, it decided that he could not veto the constitution or any part of it, but had limited veto rights over ordinary laws. This solved nothing, since he still refused to act on the August 4th decrees or the Declaration.

What was needed to force the king to act, some of the politicians said, was another uprising of the people in Paris. The food shortage was serious again and there were bread riots in Paris almost daily. Still the people as a whole were not quite stirred up to the point where they would turn in anger against the king. Something more was needed.

That something more was soon supplied by the king himself. He used the bread riots in Paris as an excuse for calling a regiment of soldiers to Versailles. His real purpose, of course, was to be able to deal more firmly with the Assembly. On October 1, a dinner was held in honour of the officers of the regiment. There were toasts to the king, but none to the nation; it was said that the red, white and blue cockade of the Revolution was trampled underfoot. The people of Paris were furious and threatened to march to Versailles and bring the king back to Paris.

On Monday, October 5, a mob of women appeared at City Hall and demanded bread and then decided to march to Versailles and see the king. More than 6,000 of them made the long march over muddy roads in the rain. Lafayette followed later in the afternoon with his National Guard. When he arrived at midnight, the women had already settled down around campfires and all was quiet.

“WE BRING THE BAKER”

Early in the morning, the women and thousands of other persons who had arrived during the night found an unguarded entrance into the palace. Some of them went in to look around and fighting broke out. Several were killed. The angry mob smashed through doors and rushed up the broad stairway leading to the queen’s apartments. The loyal bodyguard checked their advance just long enough for the queen to escape in a dressing gown to the king’s quarters across the hall.

Arriving with his National Guard, Lafayette blocked the way to the royal chambers and the mob backed away. Not a blow was struck as the people retreated down the marble stairs and out through the splintered palace doors. Once outside, they joined the screaming mob that surrounded the palace. Lafayette finally quieted them by appearing on a balcony with the king and queen and their small son.

“The King to Paris! The King to Paris!” shouted the people, over and over they went on shouting until the king agreed to come with them.

That same afternoon, the National Guard led the procession to Paris, with a loaf of bread carried high on a bayonet. They were followed by wagonloads of wheat and flour, the market women of Paris, palace soldiers and the Swiss Guard. Then came the royal carriage‚ with Lafayette riding beside it on a prancing white horse. Behind it came several hundred members of the Assembly in carriages, more National Guard units and more of the people.

“We bring the baker, the baker’s wife and the baker’s boy,” chanted the people as they marched through the rain toward Paris. They were convinced that having the king and his family living in Paris would mean plenty of bread in the city from then on.

At a welcoming ceremony at City Hall, a red-white-and-blue cockade was pinned on the king’s hat. The royal family was then taken to live in the Tuileries, a city palace which had not been occupied by a royal family for more than a hundred years. About two weeks later, the Assembly moved to Paris so that it could be in the same vicinity as the king.

The Revolution seemed to be about over. First, the nobles had revolted and their victory had forced the king to call the Estates General. Next, the middle-class representatives in the Estates General had revolted to gain control of that body. Their victory over the king and the nobles brought the National Constituent Assembly into being. Then the people in the cities and towns had revolted, gaining control of their local governments. Finally, through the revolt of the peasants, the nobles lost control of the countryside, too. The time had come, it seemed, for the Assembly to continue its work of establishing a free society under a constitution.