GREAT power had allowed Augustus to do great good for Rome and its provinces. The same power in the hands of a man who was not good meant that he could do great harm. This the Romans learned as they watched the remarkable parade of good and evil men who came to govern Rome after Augustus. Some of them were wise, two or three were foolish, one thought he was the greatest artist in the world and another said he was a god. All were the masters of Rome, mighty princes who were called emperors. The title emperor came from imperator, the Roman name for the man who commanded the armies. Every ruler of the empire owed his power to the legions. When he gave an order, his soldiers made certain that it was obeyed. If his orders became too harsh to hear, it was his soldiers who struck him down.

Augustus, like Caesar, had named the commander who would take his place when he died. The man he chose was one of his own family, the Caesars. So were the next three emperors. Two of these emperor Caesars were good and two were dreadfully bad.

The first, Augustus’ stepson Tiberius, was good, though the city mob did not think so. He treated them with scorn and, worse, he was stingy with his gifts of food and gave them very few shows. The Senate liked him even less than the people did. Tiberius was proud and he made it difficult for them to pretend that they were ruling Rome. Then, one morning, someone overheard him exclaim, as he was leaving the Senate house, “These senators, how ready they are to be slaves!” The senators, who remembered Caesar as well as Augustus, began to plot against the emperor. But he brought his own bodyguard to Rome — a handpicked corps of legionaries called the Praetorian Guard. The Senate stopped plotting and waited hopefully for Tiberius to die.

THE MAD EMPEROR

In the provinces, however, the emperor was loved. If he was stern, he was also fair. When an official suggested rough methods for squeezing more tax money from the empire, Tiberius told him sharply, “A good shepherd shears his sheep, he does not beat them.” To men who had suffered under the old governors, that seemed like kindness.

Everything about Tiberius began to seem kindly when he was dead and Augustus’ great-grandson Caligula became emperor. People suspected that he had murdered Tiberius. Some said that he had poisoned him, others that Tiberius was already sick and Caligula simply set a pillow over his face to hurry things along. Nevertheless, Caligula gave a solemn funeral speech for Tiberius and wept all the way through it.

Perhaps they were tears of joy, for Caligula loved being the emperor. As a boy, he had played soldier, dressed in a little legionary’s uniform and boots. As emperor, he could play at being a god. He built a temple to himself and a special bridge from his palace to the temple of Jupiter so that he could visit his “brother god.” Then he collected Greek statues of gods, had the heads sawed off and carvings of his own head placed on them.

Before long, hundreds of Romans were suffering the same fate as the statues, but without the benefit of new heads. Having emptied the state treasury, Caligula began to use Sulla’s old system for raising money — kill the rich and take their property. Then he had people murdered for no reason at all. When he began to call Rome “the city of necks waiting for me to chop them,” the Romans realized with horror that he was not just cruel, but mad.

The Praetorians, the royal guard, took care of the problem. One of their officers went to the arena where Caligula was attending the games. He waited in a hallway under the grandstand. When Caligula came out of the arena, the officer struck him with his dagger. The emperor fell, and his cries were drowned out by the shouts of the crowd above, cheering the gladiators. The guardsmen then rushed to the palace to capture Caligula’s courtiers. They found his uncle, Claudius, shivering in fear behind a curtain and dragged him out. Instead of killing him, they made him the emperor. It was the first time that soldiers had chosen a ruler for Rome. It would not be the last.

After Claudius got over his surprise, he began to act like an emperor. It was not easy for him. He was elderly and sensible, not at all like his wild young nephew Caligula, but no one had ever paid much attention to him before. Now everyone turned to him and he was not always sure about what to do. Wisely, he followed Augustus’ plans for running the empire. To help him carry them out, he chose a council of learned Greeks. They served him and the empire well. He also chose four wives, who served him badly. Each was worse than the one before. While the world trembled at Claudius’ words, at home in the palace he was henpecked.

His last wife, Agrippina, was a battleship among women, who wheedled and nagged him. She had married him, it was said, only because she could not be emperor herself. He did not have to hear her sharp tongue for long, however. When she had persuaded him to name her own son Nero as his heir, she fed him some poisoned mushrooms and Claudius ceased to be emperor as suddenly as he had begun.

ART AND MURDER

Nero, the new emperor, was just sixteen. With his mother to guide him and an empire to spoil him, he grew up to be the worst ruler in the history of Rome. He started off well enough. He ignored Agrippina and chose two able, honest men to advise him. His old tutor, the philosopher Seneca, took charge of the government and its officials. Burrus, the commander of the Praetorian Guard, looked after the armies. The young emperor spent his time on things that he felt were more important — singing, acting, painting pictures, writing poetry and playing the lyre, the organ and the bagpipe.

Nero was sure he was a great artist. If he was not, no man in Rome dared say so. In the Senate, however, the graybeards shook their heads and worried about the future of the empire. They were horrified when Nero acted in the public theater. Actors were not respectable citizens, they said. Neither were singers and dancers, but Nero invited them all to the palace.

The people loved it. An emperor out to have fun was something new. Of course, the old Greek tragedies he staged for them were dull, but when they booed, he brought back the wild animals and the gladiators. There was more free food, too. The Senate might complain, but Nero spent his money freely. The scandals of his court, where lords acted like street musicians and street musicians acted like lords and ladies, brought the mob some new excitement every day.

Meanwhile, Agrippina fumed. It was not so much the scandal that bothered her. She had no chance to take a hand in the ruling of the empire. She lectured Nero, calling his advisers scoundrels, thieves and worse. She coaxed him. She threatened to make his step-brother the emperor in his place. When she had had her say and Nero was feeling grumpy, Seneca and Burrus dug into the treasury and gave him money enough to put on a new spectacle. They applauded his latest poem, bought him a Greek chariot to drive around the Circus Maximus and then got back to their work of governing the empire. Nero, cheerful again, had his step-brother murdered.

Things went on this way for several years, with the emperor’s mother scolding him and his advisers comforting him at the treasury’s expense. Then Agrippina made the mistake of telling Nero not to marry a girl he had fallen in love with. Nero decided it was time for his mother to join Claudius in the underworld. Agrippina, however, was very wise in the ways of royal murder and she did not take chances. Three times Nero fed her poison; each time she had taken the antidote first. He and his workmen build a machine that would drop the bedroom ceiling on her, but she was warned about it. He sent her for a cruise on a ship specially designed to fall apart at sea, but she was a strong swimmer. Finally, he sent the army and Agrippina never lectured him again.

Burrus and Seneca left him, too — Burris died and Seneca retired. Without their help, Nero was soon in trouble and the empire was in debt. When he began to use Sulla’s kill-the-rich system, the senators began to plot against him. Then disaster struck Rome and suddenly, everything else was forgotten.

THE BURNING OF ROME

On the night of July 18, in A.D. 64, a fire broke out in the wooden bleachers of the Circus Maximus. Within minutes, all of the tinder-dry stadium was ablaze. A wind carried the sparks to the houses nearby and they, too, burst into flames. The fire raced through the cheaply-built tenements along the narrow old streets, jumped to the wooden roofs of temples and baths and roared along the colonnades crowded with shops. Nothing could stop it. Merchants and soldiers, rich men and slaves — anyone who lived near the fire ran to the fields outside the city. As the flames spread to other sections of the city, the roads became jammed with carts and wagons loaded down with the furniture, statues, gold plates and finery that people hoped to save. Nero himself left for his villa in the country. For six days, the fire burned. When the Romans dared to come back to the city, ten of its fourteen districts were in ashes.

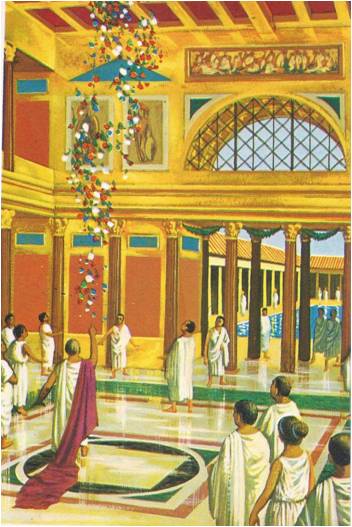

Nero returned and, for once, went to work eagerly. He called for his architects and designed a new Rome, with straight wide streets and buildings of stone and brick instead of wood. For his own use he planned a fantastic palace that was a city in itself. Its pillared arcade was a mile long. It had a vast lake surrounded with buildings made to look like little towns. The emperor’s garden included fields and vineyards and a forest with wild animals. Some of the rooms in the palace itself had painted walls, but Nero’s own apartments were plated with gold and decorated with jewels. The ceilings were designed to slide back so that showers of flowers or perfume could be sprinkled on the people below. The “Golden House” of Rome soon was known all over the world and, to remind everyone who had built it, at the entrance stood a statue of Nero, twelve stories high.

The emperor had such a good time building his new Rome that someone suggested that he had set the fire himself. Every gossip in the city had already told and retold the story about his reciting poetry to the music of a lyre while the city burned. The new rumor was just as easy to believe.

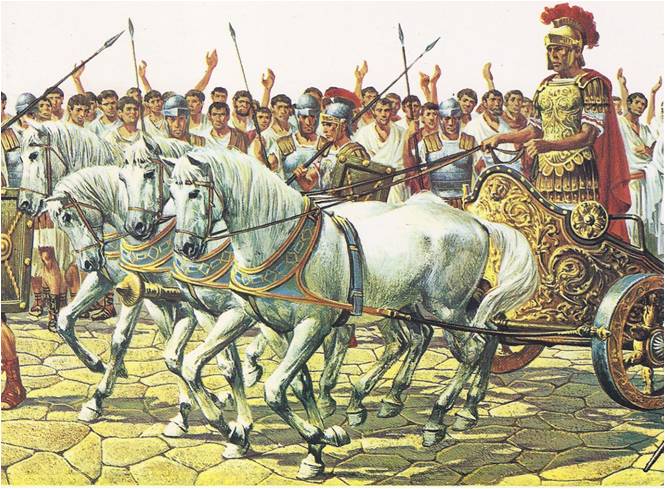

Nero had not started the fire. But, as the stories spread, he had to find someone to take the blame. He chose the Christians. They were a new religious group and troublesome, because they refused to worship the emperor. Their first leader — the reports in Rome called him Christus — had been put to death by a Roman governor during the reign of Tiberius. His followers had gone on preaching his un-Roman ideas and these followers seemed to get more numerous all the time. Nero had the Christians in the city rounded up. Then he invited all of Rome to come into the garden of his new palace to watch while some of prisoners, dressed in animal skins, were attacked by ferocious hunting dogs. The rest of the Christians were killed off in a show at the Circus. Nero took charge of the performance himself, standing in a chariot and dressed as a Greek charioteer.

The Romans were not pleased with the games. “Who knows if these Christians set the fire?” they asked. “What good can their deaths do Rome now?” They told each other that the emperor enjoyed his killings too much. They had seen his brutality before; one day it might touch them.

The emperor was busy with plans for games of a less painful sort. He had decided to give the Greeks an opportunity to see his skill in their arts. He went on a tour of Greece and commanded that the Olympics and other great contests be held while he was there. Then he entered every singing, harp-playing and chariot-racing competition at all of them. He won every time. This was not surprising, for it was dangerous to out-do the emperor. The cheering was less loud than he had hoped for, but he came back to Rome with 1,080 first prizes.

Meanwhile, the city buzzed with plots against him. Many of the great men in Rome were involved in them, despite the danger. Seneca, who had been the emperor’s adviser, joined one of the groups of plotters and was killed when Nero discovered it. The execution angered Rome and more of Nero’s friends learned to hate him. Anger grew in the provinces, too and the legions began to turn against the emperor. When the news reached the capital, the Senate found its courage. It voted to condemn Nero as an enemy of Rome and the Praetorians, his own guard, refused to protect him.

Defenseless, knowing that he was about to be arrested, Nero fled his Golden House and ran to the home of one of the few friends he had left. When the soldiers knocked at the door, he stabbed himself. “I go and the world loses a great artist!” he moaned. Then he died and so, in A.D. 68, the line of the Caesars came to an end.

Now there was no one who had a true claim to the throne of Augustus. However, the Praetorian Guard had made Claudius an emperor and they were willing to try again. When they announced their choice, three of the legions, not wanting to be left out, named candidates of their own. For a year the empire had too many emperors and no order at all.

Finally one general, Flavian Vespasianus, who had the troops of the eastern frontier to argue his rights for him, claimed the throne. The Senate agreed to let him keep it and for twelve years he and his sons ruled Rome. The Golden House was torn down, for Vespasian preferred to live in Augustus’ house on the Palatine Hill. Gilded walls and playing the artist were not for him. In fact, three years before he became the emperor, his army career — and his life — had nearly come to a sudden end when he fell asleep at one of Nero’s song recitals. Now that Rome was his, he intended to bring order, not music, to the empire.

His methods were not always gentle ones. When the Jews of Jerusalem revolted against the emperor whom they, like the Christians, would not call a god, Vespasian sent his son Titus to destroy them. After a siege that lasted for six months, Titus captured the city and slaughtered more than a million Jews.

Strangely enough, this same Titus, who became emperor when his father died, was called in Rome “the delight of mankind.” He became famous for his kindness, though perhaps the Romans were only impressed with the enormous stadium which he and his father built for them. It was called the Colosseum. Forty to fifty thousand people could watch the gladiators from the marble seats in its grandstands, protected from the sun by huge awnings manned by sailors of the imperial fleet. The outside of the stadium was just as grand — four tiers of columns and arches, set one upon another. It was a gift to win any emperor a name for generosity.

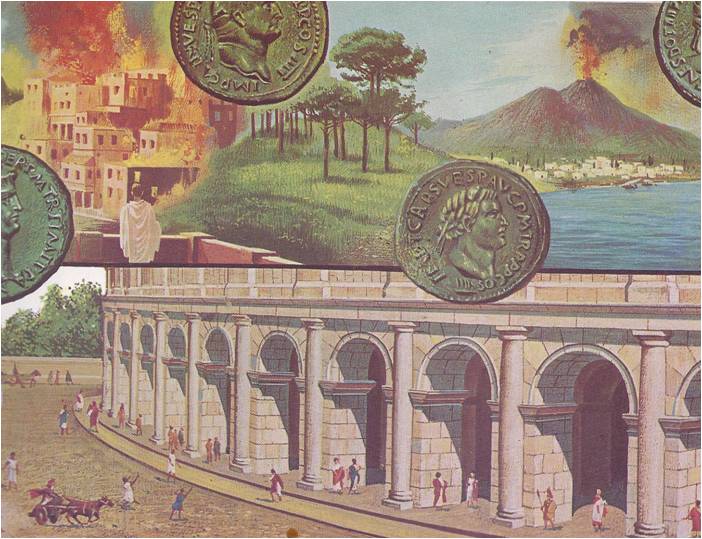

Titus’ reign was remembered as much for nature’s cruelty as the emperor’s kindness. In the short two years that he ruled Rome, one disaster after another came to Italy. There was an outbreak of the plague, then another fire in the city. In A.D. 79, the volcano Vesuvius suddenly erupted, raining fire and molten lava on the busy town of Pompeii. When the volcano grew calm again and the smoke drifted away, Pompeii had disappeared. The town, its buildings and its people lay buried under a blanket of ashes in a tomb of lava rock.

However, the rest of the Roman world was soon back to normal. The plague died down, Rome was built up again and there was a new emperor without an ounce of kindness in him. He was Titus’ brother Domitian and he set out to keep the peace no matter what cruelty was necessary to do it. His harshness shocked and frightened Rome. When people began to speak out against him, his own fear and suspicion drove him to even greater cruelty. It became dangerous to talk in the streets, because the emperor imagined plots where there were none. Of course, when he punished people for imaginary plots, the real plotting began. Finally, his rages made even his friends afraid for their lives and he was murdered by his officers and his wife.

“PEACE, NOT WAR”

Rome had had enough of military rulers. When Domitian was out of the way the Senate was quick to name its own man as the emperor, before the legions had a chance to act. The man they had chosen, Nerva, lived for only two years. That was just time enough for him to learn that it took a soldier, not a senator, to control the armies which gave the emperor his power. With the Senate’s approval, Nerva adopted as his heir a general from Spain. His name was Trajan and he rivalled Caesar in his ability to command troops.

Trajan dreamed of adding new lands to the empire For five years, from AD. 101 to 106, he and his soldiers battled the Dacians, the fierce barbarians who held the territory beyond the Danube. The legions were in top fighting form and their emperor was the finest commander under whom they had ever served. When he returned to Italy, Dacia was a province of Rome. Trajan celebrated his victories by building a huge new forum in the city. In its center, he set up a stone column with carvings that told the whole story of the war.

A few years later, Trajan marched the legions against the Asians in the Tigris-Euphrates valley. His new campaign was not a success and finally he had to admit that it was senseless to go on with it. Worn out and disappointed, he began the journey back to Rome. On the way, he was taken ill and died.

Hadrian, the new emperor, was as brilliant a soldier as Trajan, but like Augustus, he was also a statesman. He knew that the Roman world had needs that were more important than extra land. It needed his legions to keep its frontiers safe and his treasury and his laws to make life better on the land it already owned. “The business of the emperor,” Hadrian said, “is peace, not war.”

Rome’s days of conquest were over.