Zealots, for sixty years or more, had formed the “resistance’’ against the Romans in Judaea and their ideas were shared by many other Jews who were not active members of their party. After the death of King Agrippa in A.D. 44, Judaea returned to direct Roman rule and from that moment Jewish history seemed to take on an air of inevitability. According to orthodox Jewish belief the Holy Land belonged to God and God alone. The presence of a Roman Governor in Jerusalem was in itself an affront to God and to pay tribute to the Emperor was to give to a non-believer what was God’s by right. Tension and disorder steadily increased, stimulated by Roman maladministration, Messianic excitement and nationalist activity. The fatal explosion finally came in A.D. 66. With the resulting loss of their land and the Temple at Jerusalem, the Jews’ religion ceased to be a religion that demanded the ritual of sacrifice and the people themselves were scattered abroad without a national home until the present century. In the summer of the year 66 the priests of the great Temple of Yahweh in Jerusalem refused to offer their customary daily sacrifices for the well-being of the Roman Emperor and people. These sacrifices were an accepted token of Israel’s loyalty to Rome and a refusal to continue making them was tantamount to a declaration of revolt. The priests concerned were members of the lower order of the Temple clergy, who subscribed to Zealotism. General view of Jerusalem Behind this refusal of the lower priests lay a complex situation. The higher clergy, who formed a priestly aristocracy, were presided over by the High Priest. This aristocracy supported the Roman government of Judaea because it ensured their own social and economic position; the maintenance of the “loyal” sacrifices was …

Read More »Revolt and Destruction of Judea (30 – 70 A. D.)

Judea was destroyed and it’s people were scattered due to revolt in the East. Herod the Great died in the spring of 4 B.C.; his death sparked off an explosion of the long pent-up feelings of his Jewish subjects. Revolts immediately broke out in different parts of the country under various leaders. The situation was made worse by a Roman procurator, Sabinus, who moved in with troops to secure Herod’s very considerable property for the Emperor Augustus. At Jerusalem, crowded with pilgrims for the feast of the Passover, armed conflict soon broke out. The Romans were ordered to withdraw by the rebels, “and not to stand in the way of men who after a lapse of time were on the road to recovering their national independence.” This statement of Jewish aims, which is recorded by the Jewish historian Josephus, is significant. It embodied an ideal, inspired by traditions of the heroic days of David and the Maccabees, which was rooted in the peculiar nature of Jewish religion. Every Jew was brought up to believe and the belief was reinforced daily by the study and practice of the Torah — that Yahweh, the god of Israel, had given his people the land of Canaan as their Holy Land, where they were faithfully to serve him. This belief implied a conception of the state as a theocracy; Yahweh owned it and was its sovereign lord, and his vice-regent on earth was the high priest. This conception in turn implied the freedom of the Jewish people to devote themselves to the maintenance of this theocracy. Judaea under Roman rule The Jewish revolt, which was apparently uncoordinated, was eventually suppressed by Varus, the Roman governor of Syria, who intervened with two legions and ruthlessly crushed the rebels, two thousand of whom he crucified. What …

Read More »Jesus of Nazareth, Saviour God of a New Religion (30 A.D.)

Jesus of Nazareth, his life and death, for Romans alive about A.D. 30 was of no significance whatsoever. In the context of Roman history, Jesus was just another rebellious troublemaker. After the revolt of Spartacus thousands of slaves had been crucified in the same way as Jesus. His death was merely one more item in the list of repressions that Rome found necessary to carry out in order to consolidate her power. Yet in the end, the religion founded by Jesus would take over the Roman Empire itself and eventually make its way all over the world. The consequences for the subsequent history of civilization were incalculable. Writing early in the second century, the Roman historian Tacitus told his readers how Nero had been suspected of burning Rome in A.D. 64. To free himself from suspicion, the infamous Emperor “fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their vices, whom the people called Christians. Christus, from whom the name derived, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius on the order of the procurator Pontius Pilate. The pernicious superstition, suppressed for the moment, broke out again, not only in Judaea, the source of the evil, but in Rome itself… . Accordingly, acknowledged members of the sect were first arrested; then, upon their evidence, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred of mankind.” This significant passage from the Annales of Tacitus shows what an educated Roman knew and thought about Christianity some eighty years after its birth. To him it was a dangerous subversive movement whose founder had been executed for sedition by the Roman governor of Judaea; but that had only temporarily checked the movement and it had spread from Judaea to …

Read More »Arminius, Liberator of Germany (9 A.D.)

By 9 B.C. it seemed that Augustus’ ambition to extend Roman territory to the Elbe had almost been achieved, but the Romans overestimated the extent to which they had successfully assimilated their new province. Encouraged by revolts in the Empire, German aspirations to freedom and prowess in arms both found their champion in Arminius, a German by birth, but also a Roman citizen. Arminius’ knowledge of the terrain made a German victory a strong possibility and his annihilation of the legions sent to maintain order shook the Empire to its core. Rome was forced to abandon any idea of a province beyond the Rhine and the implications for the future of Europe were incalculable. Augustus pushed the frontiers of Roman dominion outward in almost every direction, but during the forty-five years of his sole rule he was forced to fight constant and simultaneous campaigns to maintain the lines he wished to draw on the map of Europe. The frontier between the subject province of Gaul and barbarian Germany was to prove especially troublesome and the whole might of Rome eventually was to be challenged by one barbarian leader, Arminius, of the Cherusci tribe. Arminius, whom Tacitus called the liberator of Germany, was not the first German to threaten Rome. Around the end of the second century B.C., two barbarian tribes, the Cimbri and the Teutons, had gradually migrated southward from the neighbourhood of Jutland until they reached the northern frontier of Rome. After pushing the Roman armies as far south as Orange, in the Gallo-Roman province of Narbonensis, they proceeded toward Italy itself. They were stopped, however, by one of Rome’s outstanding generals, Marius, who defeated them at Aix-en-Provence in 102 B.C. and obliterated them at Vercelli the following year. Germanic pugnacity engraved itself upon the Roman mind and tongue: …

Read More »Octavian and the New Roman Empire (B.C. 31 – 9 A.D.)

Octavian delivers the state from that was plunged into depression. A few weeks after January 1 in the year 29 B.C. the doors of the temple of Janus in Rome were closed. This traditional act symbolized that the Roman state was at peace. The closing of the doors on this occasion was greeted with more than the usual joy and relief that marked the termination of war. Since the murder of Julius Caesar in the Forum in the year 44 B.C., Rome had been plunged, with little intermission, in civil war. From that long agony, the state had finally been delivered by Octavian’s victory at Actium and the subsequent deaths of Antony and Cleopatra. The Senate and people of Rome were, in consequence, deeply grateful to the man who had brought them this relief, and they were disposed to accept his leadership. Augustus Octavian Supreme Octavian knew this and recognized the strength of his present position, but he was also astute and cautious, as well as being a statesman profoundly concerned with the future well-being of Rome. He perceived what were the realities of power and what were its trappings; and he was careful never to confuse the two. Augustus with the goddess Roma His uncle, Julius Caesar, of a more flamboyant nature than his own, in the moment of his power had offended Republican principles and had fallen beneath the knives of ardent Republicans. The civil war had taken a heavy toll of these Roman oligarchs; but even in the year 29 Rome was still officially and by a long and revered tradition, a republic. It would be imprudent to disregard the fact. Weaknesses of Republican Structure The civil war and the struggle between Pompey and Caesar that had preceded it, had revealed the weakness of the Republican constitution. It could …

Read More »The Emperor Augustus (B.C. 31)

The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C. initiated thirteen years of bloodshed, during which the people who had plotted his death were hunted down and those who remained in positions of power disputed that power among themselves. Finally, the struggle resolved itself into a duel between Octavian, Caesar’s grand-nephew heir and Marc Antony, his most able lieutenant, in alliance with Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt. In the final confrontation at the naval battle of Actium, Marc Antony and Cleopatra were routed and Octavian became ruler of the world as the Emperor Augustus. Egypt’s last bid for world empire had been thwarted. More importantly, the work begun by Julius Caesar was continued and the transition from the anarchy of the end of the Roman Republic to the glory of Empire was completed. Late in the summer of 31 B.C., the two largest fleets the world had ever seen confronted each other off the northwestern shores of Greece. The four or five hundred warships of Marc Antony, including sixty belonging to Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, faced outward into the Ionian Sea. Against this navy stood another of approximately equal size, which had come with the young Octavian, the future Emperor Augustus, from Italy. War had been declared against the foreigner Cleopatra and by implication, against Antony, her husband in Egyptian, though not in Roman law. The crews on each side numbered well over a hundred thousand men. Apollo of Actium; a Roman coin issued by Augustus, for whose victory in the battle the god Apollo was held to have been responsible. Behind Antony’s ships, on the opposite banks of the narrow channel leading into the Gulf of Ambracia, were posted the two rival armies, each more than eighty thousand strong. Octavian’s troops had come from Italy and landed at a port in …

Read More »The Roman Republic is Reborn with Imperial Splendour (73 – 31 B.C.)

The happy judgment of the historian Polybius on the strength of the Roman constitution, because of its mixture of popular, oligarchic and monarchical elements, might certainly appear as an optimistic theorization after the revolt of Spartacus. The Roman state had been shaken by a bitter and violent social disturbance that had only been resolved by two individuals whose power, though technically constitutional, was far too great for the Senate to feel comfortable. Crassus, the multimillionaire and Pompey, the popular general — had succeeded where the regularly appointed consuls had failed and the “extraordinary commands” with which they had been vested were a de iure recognition of the fact that the Roman state was now on the brink of being run by powerful individuals. The existence of such extraordinary commands, continuing until Octavian resolved the power struggle by his Victory at Actium and set about establishing the Roman Empire, with one individual in permanent possession of autocratic powers, indicates that the needs of the Roman state could no longer be met by using the established constitutional procedure. In the earlier days of the Republic, generals had been given special authority in the face of a serious military threat, but the Senate had carefully limited their authority and had been strong enough to keep control. If we look back at the period of Rome’s expansion into the Mediterranean, we shall see that the Senate had in fact, grown in strength, but that its increasing influence in government, also brought with it the potential for individuals to influence affairs. Sacrificial procession of the Roman Republic The Roman Senate During the Roman republic’s period of wars and expansions, from the time of the Punic wars onwards, the Senate, composed as it was of men whose experience and status gave them the ability to judge …

Read More »The Slaves Revolt (73 B.C.)

As Rome’s armies marched victorious across the known world and her fleets patrolled the Mediterranean, hundreds and thousands of slaves were shipped back to Italy as cheap and expendable labour for the vast estates of the rich. Many worked in chain gangs under the lash of brutal taskmasters or were sent as shepherds to the milder parts of the country. Others were put into gladiatorial establishments, where a cruel and bloody death was an almost certain fate. In such conditions revolt seemed inevitable and after an unsuccessful attempt in Sicily in 135 B.C., a new revolt, under the leadership of the Thracian, Spartacus, exploded in 73 B.C. An army of 40,000 under Crassus was needed to restore order and 6,000 slaves were crucified as a warning to their fellows. Despite its immediate failure, the revolt hinted that the days of the Roman Republic were now numbered. One day in June, 73 B.C., seventy-four gladiators broke out of their training establishment at Capua in southern Italy. They armed themselves with weapons stored for training and arena fighting, cut their way through the city and marched across country to Mt. Vesuvius. There near the top they made camp and soon slaves from the towns and farms joined them. The leaders were the Thracian Spartacus and two Gauls, Crixus and Oenomaus and their force included a strong contingent of Gauls and Thracians. From the outset, Spartacus dominated: it was he who had doubtlessly organized the breakout from Capua. The alarmed authorities sent G. Claudius Glaber, a praetor of the year, who tried vainly to surround and dislodge the rebels. However, the emboldened slaves came down the slopes and roamed about the south, scattering detachment after detachment of troops. Soon they were masters of the whole south and their ranks were swollen with runaway …

Read More »Slaves in the Ancient World (217 – 73 B.C.)

Slaves could be imported to Italy when and where they were needed. The demand for labour was immediate and there was a much faster and more predictable solution to such a demand, than encouraging population growth or attracting the movement of free workers. The expansion of Carthage was brought to a grinding halt when the genius of the Roman general Scipio enabled the Romans to defeat the Carthaginians decisively on their own ground, at Zama in North Africa. Hannibal lived out the rest of his life in haunted exile, forever planning to challenge the might of Rome again, whether on behalf of Carthage or one of the Hellenistic kingdoms. Rome was now undoubtedly mistress of the western Mediterranean. The dangers that she had experienced at the hands of a Greek leader, Pyrrhus, were not forgotten, so she also determined to keep a watchful eye on the East. She set about systematically fore-stalling the rise of any potentially dangerous rival in Greece, taking the side of the weaker party against the stronger in political quarrels, to maintain a certain balance of power. Philip V, King of Macedonia, the chief aggressor in Greece, was driven out and a protectorate was set up. Greece was again aided against an “aggressor” when the Syrian Antiochus III, the Great, invaded. He was hounded into Asia Minor by a Roman army and heavily defeated. Roman influence then rapidly spread over Asia Minor. Pergamum became a client-kingdom and discord was promoted in Syria so that no strong centralized control remained. In Egypt, the Ptolemaic kingdom was given Roman “protection” and this loose form of protectorate lasted until Egypt became an integral part of the Roman Empire after Actium, the subject of one of our subsequent chapters. Greek warrior The Rise of Rome From the ashes of Alexanders …

Read More »Hannibal Challenges Rome (217 B.C.)

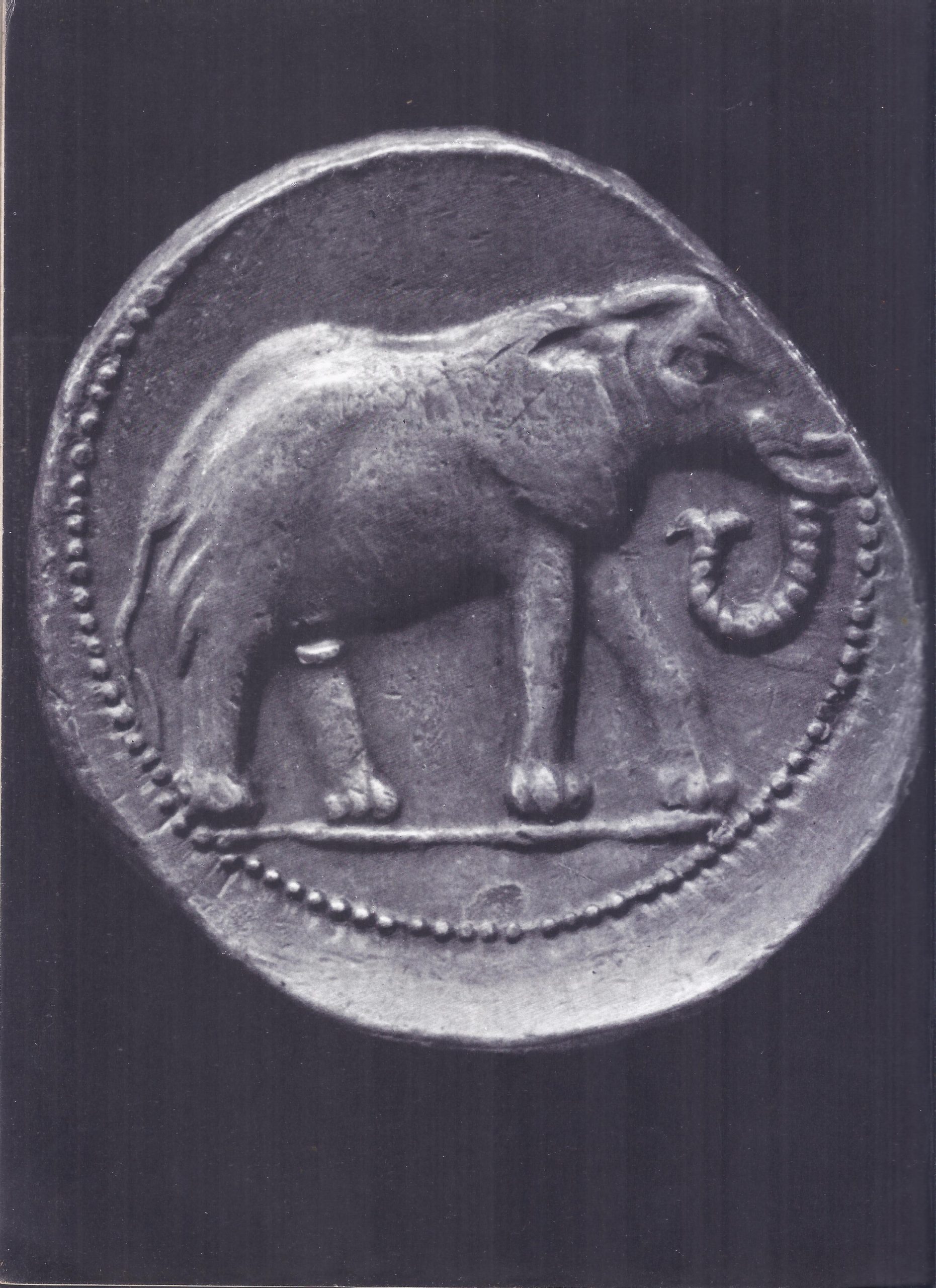

Hannibal alone, would have dared embark on such a venture. Two powers confronted each other to dispute mastery of the Mediterranean — Rome and Carthage. The Carthaginians were interested in colonial expansion as an extension of their trading interests, but were prepared to protect those interests if necessary. Rome’s view was essentially different. In fact, some Romans believed that the fates of the two nations were inextricably linked and that they were doomed to a duel to the death. Carthage’s sphere of influence extended over a great deal of the western Mediterranean, so Rome had to become a naval power virtually overnight. Carthage too was arming for the confrontation and under the leadership of the general Hamilcar moved the theatre of war to Spain. It remained for his son Hannibal — one of the greatest military geniuses of all time — to challenge the Romans on their homeground by crossing both the Pyrenees and the Alps. In the ancient world such a feat seemed impossible. In the spring of 218 B.C., an army of 100,000 men gathered in a town in eastern Spain, now Cartagena, under the command of a young general, Hannibal Barca. These soldiers had been recruited from all the warlike tribes of Spain and North Africa. The officers were Carthaginians, descended from the ancient Phoenician people who had left the Lebanon six or eight centuries earlier and had colonized first the coasts, then the interiors of present-day Tunisia and Andalusia. In the next two years these men were to accomplish one of the most astonishing feats of history. They were to travel more than 1,200 miles through hostile or savage countries, crossing one of the biggest rivers in Europe and two of the highest mountain chains. At the end of this formidable journey they were virtually to …

Read More »