Although the Exodus of the “children of Israel” from Egypt is rightly to be regarded as one of the greatest milestones in human history, in the context of the age in which they lived it must have seemed a very small, even trivial event. The Egyptians themselves would have regarded it as just one more tiresome episode in a constantly recurring situation. For centuries the bedouin tribesmen of Sinai and south Palestine had been permitted from time to time to bring their flocks to the fringes of the fertile Delta in search of pasture; whenever there was famine on the steppelands, the cry would go around, “There is corn in Egypt!” From time to time, when the nomads, grown numerous, sought to move farther in and settle, the army of Pharaoh would be sent to expel them from the borders once more. They had outstayed their welcome. Statues at Abu Simbel Archaeology has not yet provided any material remains that could throw light on the story of the sojourn in Egypt and of the Exodus. Circumstantial details contained in the narrative, however, and our knowledge of the wider history of the age, suggest that Joseph and Moses fit best into the context of the Nineteenth Dynasty, when the residence city of the Pharaohs was not Thebes or Memphis, but Pi-Ramesses in the eastern Delta, probably that same city called “Raamses” which the Hebrews are said to have helped to build. The Pharaoh of the Exodus in that case is likely to have been Ramses II, who founded this new city and embellished it with fine buildings and gardens. Egyptians harvesting corn The Reign of Ramses II Ramses II is one of the most impressive figures in the whole history of the ancient Near East. His long reign of sixty-seven years …

Read More »Let My People Go! (Hebrews 1280 B.C.)

The Hebrews were a nomadic people, some of whom settled in Egypt. They had their own God — Yahweh or Jehovah — and in this respect they differed little from the people around them. Yet the Israelites, led by Moses, were convinced that their God had promised them a land of their own and that they must leave Egypt and go to Palestine. Their God was essentially a god of battle and as such, invaluable as long as they were on the march. What would happen once they settled down? Inevitably there were attempts to worship local gods also, but the basic conviction that there was only one god — and a moral god at that — the God of Israel and that the Hebrews were his people, was never forgotten. For this reason the Hebrews are one of the most important peoples of antiquity. The Exodus or departure from Egypt was essential to the fulfillment of that role. The blazing heat of early summer beat down upon the rocks and sand of the vast and mountainous wilderness of Sinai. In a parched valley, far from any human habitation, a band of some hundred Hebrews, perhaps even some thousands of fugitives from the Nile Delta waited for the orders of their leader, Moses. These “children of Israel” (Hebrews) formed part of a group of tribes who had migrated into the Land of Canaan from the north several hundred years earlier. All Hebrews claimed a common ancestor in Abraham and all shared a common religious belief. Then famine had struck the land, probably in about 1650 B.C. Some of the tribes of the Hebrews had found food nearby; others, the ancestors of Moses’ group, had wandered as far as Egypt in the search for sustenance and they had remained there as …

Read More »Palestine to Egypt – People Gain a National Identity and Settle New Lands (1400 – 1280 B.C.)

Palestine was possessed by Egypt. In the year 1887 an Egyptian peasant, digging in the ruins of an ancient city on the banks of the Nile, came across some baked clay tablets impressed with cuneiform writing. In due course these tablets came into the hands of dealers and eventually their importance realized. The city had once been the capital of Egypt, for a brief time in the early fourteenth century B.C. and the tablets had come from the record office of the palace; they were letters, part of the files of the Foreign office, the correspondence of the potentates and princes of the Near East with their ally, or in some cases their overlord, the Pharaoh of Egypt. They are written in Akkadian: the language of diplomacy in this age, as it had been in the time of the Mari letters and we must imagine that in every prince’s palace, even in countries remote from Babylonia, there were scribes who could read and write the language and would translate the letters to their masters. The situation mirrored in these letters is a complex one. Tribute-bearers from Carchemish The kings of Babylonia and Assyria, the kings of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni and of the kingdom of Alashiya, which may be Cyprus, wrote to the Pharaohs as equals. They were bound to them by treaties of alliance cemented by marriage and some of the letters discuss the amount of dowry which they propose to give to a daughter who is to be sent to Egypt to swell the Egyptian king’s numerous harem. Rich presents were exchanged and the vassal was to send a gift of gold equal value. Avenue of rams at temple of Karnak This was, in fact, trade: an exchange of goods, value for value, on an official basis …

Read More »The Aryan Invasion of India (c. B. C. 1400)

Aryan peoples from the North descended into India, radically affecting the native civilization, round about between 1750 to 1400 B.C. Some four thousand years ago in India, around the Indus Valley at Mohenjo-daro and farther north at Harappa, a civilization flourished rivaling those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Streets were laid out at right angles, brick houses existed and an elaborate drainage system was installed. Writing had also been invented. Pottery was produced and there were certainly trading contacts with Mesopotamia. They were not simply invaders — though archaeology has produced evidence of fighting at Mohenjo-daro — but settlers. The Aryan invasions were infact migrations of peoples. Among other things they introduced the horse — hitherto unknown — to India, but much more significantly, they brought a new language and a new religion, whose effects are still profoundly important in India today. The Indian subcontinent, bounded on the north by the mountain ranges of the Himalayas and elsewhere by the ocean, has always been relatively immune from invasion. The would-be invader must show an extraordinary degree of resourcefulness and tenacity if such natural obstacles as these are to be overcome. On only two occasions in historical times has India been invaded: by the armies of Islam in the Middle Ages and by the British (a process of gradual infiltration rather than direct invasion) in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Of the “prehistoric” invasions, that of the Aryans in the second half of the second millennium B.C. has left the profoundest marks on Indian culture and may fairly be called a milestone in Indian history. The precise dates and conditions of the Aryan invasion, for reasons we shall discuss later, may still elude scholarship, but this much is clear, between 1750 and 1400 B.C. India was forced to meet the onslaughts of waves …

Read More »Egypt Becomes an Imperial Power (1450 – 1400 B. C.)

We have seen that after the fall of Babylon in 1530 B. C. and the collapse of the Amorite kingdoms of the Euphrates area and North Syria, new peoples of different races entered the area and a new pattern of settlement developed. In the sixteenth and fifteenth centuries, the focus of our interest leaves the valley of the Two Rivers and is concentrated rather on Syria and Palestine and in particular on the new kingdoms which, with a population now partly Semitic (or “Canaanite,” the Biblical writers’ term) and partly Hurrian and often with an Indo-European aristocracy, were emerging as political entities. Their history is bound up with that of the rulers of Egypt, which now for the first time becomes an imperial power with widespread influence and far-reaching commerce. Egypt in the Lebanon The coastal plain of the Levant, later known as Phoenicia and the Syrian hinterland as far as the Beqa, that is to say, the valley dividing the mountain ranges of Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon, had for some centuries past been in contact with the civilization of the Nile Valley. Originally, Egyptian influence had been confined to Byblos, a well-favoured port north of the modern city of Beirut and the forested slopes behind; from here, since the earliest historic period and perhaps even earlier, the Egyptians had brought the long timbers of pine and cedar they needed for shipbuilding, which were conspicuously lacking in the valley of the Nile. Their interest had spread during the Middle Kingdom to include other parts of the Lebanon with which they established a trading relationship; in Palestine they may even have achieved some kind of military domination during the Twelfth Dynasty. Egyptian soldiers marching Egyptian influence had declined, however, as soon as the strong hand of the Twelfth Dynasty Pharaohs was withdrawn. …

Read More »The Eruption of Santorin – (B.C. 1450)

By 2000 B.C. Crete, and its out post the island of Santorin, was the home of a remarkable, flourishing civilization. Known as Minoan, after the legendary King Minos, this civilization ranks with Mesopotamia and Egypt as one of the great centres of human development and progress. The Cretans were great seafarers and traders, they soon carried their civilization to other islands of the Aegean and to the Greek mainland. Archaeology has shown us that round about 1700 palaces in Knossos and Phaistos, the two chief towns of Crete, were destroyed by fire. They were rebuilt, however, and a bright new chapter seemed to open up for Crete. Then suddenly an even greater disaster overtook Cretan civilization, on a scale unknown since. The whole of Santorin exploded, with devastating effects for the surrounding area. From that day Crete never recovered. The legend of Atlantis a tale, first told by Plato, of a great centre of civilization suddenly and violently destroyed by the sea has inspired generations of scholars to speculate on the possible historical reality of a lost continent. Some have subscribed to the theory that Atlantis may have been the Aegean island of Santorin, a flourishing outpost of Europe’s earliest civilization, the one that took root in Crete during the third millennium B.C. For early in the fifteenth century B.C., Santorin and Crete were hit by a series of natural disasters on a scale that has never been repeated in the civilized world. Archaeological exploration will no doubt continue to reveal more about this cataclysmic series of events; meanwhile, we know enough to show how remarkable was the civilization these islanders had created. Patterns of Spirals are found on many Cretan artifacts of the Bronze Age and may have been the origin of the spiral patterns that became popular in Egypt …

Read More »Hittites – A New Power Arises (1750 – 1450 B.C.)

Hittites, a new power, arises in the Near East and Babylon is eclipsed. The Babylonian kings who followed Hammurabi were unable to hold the wide territories that he had won. New enemies challenged the supremacy of Babylon in Mesopotamia; the south broke away and a new kingdom came into being, the dynasty of the Sea Land, with its centre in the marshy region around the head of the Persian Gulf. The Babylonian army was more than once defeated by the Cassites, a mountain people from the region now known as Kurdistan. In the northwest, the Mari region regained independence. From the encircling highlands, barbarian newcomers were pouring into the semicircle of river valleys and urban settlements known as the Fertile Crescent. The ethnic map of the Near East was undergoing the first of a series of violent changes, perhaps the most far-reaching of all in its effects on the history of man. Map off Babylon c. 600 B.C. Cosmic Order A motif that recurs in the mythology of many ancient peoples is that of the emergence of order from disorder, of cosmos out of chaos. This is the theme of the creation legends of Mesopotamia and of Egypt. The concept of cosmic order, which the gods bring about and which mankind is concerned to maintain, is present in many ancient literatures. It implied the taming of the forces of nature, storm, fire and flood; and the defense of civilization against dangers from without. These dangers were ever-present, for throughout the whole of the ancient period and for many centuries afterwards, the areas of civilization were islands in a vast ocean of barbarism. To appreciate society and to understand its history, we must know something of this great hinterland of barbarian peoples, for their periodic incursions often constituted milestones of deep …

Read More »Hammurabi – The First Law Code (1750 B. C.)

As the political state evolved, the problem of its administration evolved too. The territory ruled over by Hammurabi of Babylon was composed not simply of two adjacent areas with similar characteristics — as in Narmer’s Egypt — but of former independent states with very different traditions. Hammurabi had extended his territory by conquest, but as overlord he proved a conscientious ruler, dedicated to reform, and possibly the greatest tribute paid to him by his subjects was the comment, preserved in the chronicles of the country: “He established justice in the land.” Inscribed on a stone, the memorial of his justice was providentially preserved for all time, despite its being carried of to Susa by an Elamite king early in the twelfth century B.C. Regardless of the fact that Hammurabi’s immediate successors were unable to hold on to the territory he had won, his legacy to mankind constitutes a momentous milestone in the progress of human achievement. Sometime toward the end of his reign, the great Babylonian king Hammurabi (c. 1792 – 1750 BC) inscribed a code of “laws” on a tall stele of hard stone. It was neither the first nor the last document of its type in Mesopotamia: at least half a dozen similar codes are known, of which the oldest dates from the end of the third millennium, but none of them so deserves to be considered the classic of its kind; no other is so broad in its scope and of such intellectual and literary perfection. The Code of Hammurabi, in fact, provides both a brief history of and a triumphant monument to, his reign. It is only toward the end of his life that a monarch feels the need to draw up an honours list of his successes and to give a summary of his experience …

Read More »Early Culture Existed for Centuries

Early culture, between 3000 to 1750 BC, in Mesopotamia, the land between the rivers, another civilization is already far advanced. The ancient Egyptians can be said to have been the first ancient people to create a national state. Another ancient people, however, can claim priority over the Egyptians in the invention of some of the arts of civilization and in the development of urban life. These were the inhabitants of the early culture of ancient Mesopotamia, now called Iraq, the land through which the Tigris and Euphrates, the Twin Rivers, flow. In the southern part of this land the inhabitants were of the early culture of Sumer. Excavations have shown that at a time when the Egyptians were still simple fishermen living in wattle and daub huts, using flint tools and storing their grain in baskets, there were people living in the valley of the Euphrates who already lived a life of some sophistication, in walled towns which (since this is a relative term only) we may call cities. They had built imposing towers and temples of mudbrick, ornamented with mosaic and fresco; and had achieved considerable technological mastery in stone-cutting, metallurgy and the potter’s craft. The most remarkable evidence of this urban early culture comes from Warka, about two hundred miles from the present head of the Persian Gulf, which was the site of ancient Uruk — the Biblical Erech. Similar remains of early culture, dating to the middle of the fourth millennium B. C., have been found at Ur, Nippur, Eridu, Lagash and many other sites in Sumer; also farther north at Mari, on the Euphrates near its junction with the Khabur and at Tell Brak on its headwaters. Urnanshe of Lagash with his family. Life in Sumer Agriculture and dairy farming were the bases of life in …

Read More »3000 BC – Gift of the Nile

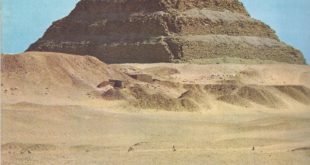

On the long road to civilization, the emergence of the national state –particularly in the context of the world in which we live — is of paramount importance in 3000 BC. Although other countries, in particular Mesopotamia, modern day Iraq, developed some of the arts of civilization earlier, Egypt was the first country to draw itself together with a national identity. The documents that survive from the period 3000 BC are few and therefore it is all the more remarkable that we know as much as we do about the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. The invention of writing occurred in Egypt shortly before the event, but there is no written history on which to rely. However, the significance of the event is plain for all to see. Under successive dynasties of pharaohs the country prospered and its civilization flourished. The brilliance of the Egyptian achievement and its continuity have inspired and influenced mankind profoundly. The Unification of Egypt in 3000 BC If you travel south from Cairo, along the west bank of the Nile, you will see on your left a narrow strip of bright green vegetation, sometimes shadowed by palm groves and ending suddenly in the broad, slow-moving, mud-brown river. On your right the vegetation ends abruptly, and beyond it the Western Desert begins, a ridge of golden, wind-blown sand, sprinkled with eroded rocks that look as if they had been baked and split by the fierce sun. The road swings to the right, climbs the desert ridge and suddenly you see before you a mighty pyramid built in steps, surrounded by a high wall enclosing a large courtyard; and not only this but many other pyramids rising out of a plateau of billowing sand that stretches endlessly to the west, as sterile and hostile as it …

Read More »