THE STREETS of Constantinople were thronged that Tuesday morning in January of 532. Public buildings were closed. Shops on the Street of the Silversmiths were barred and shuttered. The barracks at Strategium were occupied by regiments of soldiers which had recently arrived from the frontiers. The soldiers had orders to stay in their quarters, for this was a day of the people. It was the opening day of the great chariot races at the Hippodrome.

Most of the people in the crowded streets wore winter cloaks and carried their lunches. Ordinary citizens did not wear Roman togas, for that was the dress of high officials. There were beggars in rags, shaven Bulgars wearing iron-chain belts, oriental merchants in turbans and flowing robes, black-haired Asians with pointed beards, Russians in furs and seamen from Genoa and Venice.

At the Hippodrome, groups of local farmers led by priests were among the first to take their seats in the marble tiers above the vast arena. Banners whipped in the wind as the tiers filled up. Latecomers jammed the promenade that ran along above the highest of the tiers. The usual first-day excitement gripped the huge crowd, about forty thousand in all, but something was missing. People looked more serious than usual and spoke to each other in low voices. It was plain that they were uneasy.

Their uneasiness had to do with the peasant from Macedonia who had been ruling over them for several years as Emperor Justinian. This first day of the races was the time when people could meet their emperor face to face and express their feelings toward him. They had some strong feelings about Justinian. They feared him, too, and that was the reason for their uneasiness.

RIOT AT THE HIPPODROME

Justinian knew that the people were complaining, but they were his subjects and he was not much concerned with their feelings. He and other Byzantine emperors who came after him were among the most powerful rulers the world has ever known. An absolute monarch‚ Justinian was the head of everything, including the church. As commander-in-chief, he controlled the army and navy and could make war or peace as he wished. He had complete control of the government and its officials. He made the laws. He was also the supreme judge of the land, for, as he pointed out, “Who should be capable of solving riddles of the law and revealing them to men if not he who alone has the right to make the law?”

Christianity added new dignity and glory to the emperor. It made him the “Anointed of the Lord,” the “Vicar of God on earth,” and “Equal of the Apostles.” He lived in the “Sacred Palace.” His orders were “Celestial Commands.” Justinian wrote, “It is not in arms that we trust, nor in soldiers, nor in generals, nor in our own genius; we set all our hopes on the providence of the Holy Trinity.” Every act of the emperor was inspired by God and could therefore not be questioned. If he declared war on barbarians, it was a holy war for the greater glory of God. So the emperor held his holy presence at a distance from the people. Even high-ranking officials could not approach him without first lying face down on the floor three times and kissing his feet and hands.

Yet there were limits to the emperor’s power. It was his duty to respect the laws of the Roman people. There was a feeling that power to govern rested with the people and that the emperor received his power from them. A new emperor had to be recognized by the people, as well as by the army and the senate. This was mainly a matter of form. The only real power the people had lay in their “right to revolution.”

Of the people in the Hippodrome that day there were probably very few, if any, who even thought of open revolt. Justinian was still highly respected by most of the people, though he had made some powerful enemies. Among them were generals whom he had passed over in promoting young Belisarius to active command on the Persian front. Almost all men of wealth, heavily taxed for the first time, had turned against Justinian. These included senators, noblemen with large holdings of land and rich merchants. They blamed Justinian for the high taxes they had to pay, but most of their anger was directed at his head tax collector, the ruthless praetorian prefect, John of Cappadocia.

John was a big man with the manners of a bear and a remarkable ability for getting things done. To his practical mind it seemed only right that people should be taxed according to their ability to pay. He believed that the ancient Roman tax policy of going easy on the rich was wrong and he went after them without mercy.

This was reason enough for the rich to hate John but the poor hated him as well — and they, too, had their reasons. There had been no free wine at the harvest festival at Hebdomon Park, nor had silver coins been showered in the streets on Christmas Eve. Now free entertainment at the Hippodrome had been cut to merely one week of racing.

It was probably a combination of these complaints that had caused a riot in the streets several days earlier. A number of innocent bystanders had been killed. Seven leaders of the riot had been arrested and condemned to be hanged. During the hanging, two of them somehow broke their ropes and fell to the ground. Sympathetic spectators had helped them escape to the St. Lawrence Church, where they were safe, for soldiers were not allowed to enter holy places to make arrests.

These two were still in the church and the church was surrounded by soldiers of Eudaemon, who had charge of local matters within the city. The two men were very much on the minds of the people who sat waiting for the races in the Hippodrome. They believed that the men had been saved from hanging by a miracle of God and that the miracle was proof of their innocence. It was wrong to hold them in the church. it was against the will of God. Surely the emperor would see that and have them released at an once.

The races would not start until the emperor arrived and took his seat. Everyone kept watching the roofed gallery where Justinian would sit on the throne chair behind a low railing. There were places on each side for his attendants. Below the imperial balcony were four bronze horses and the terrace where the palace guards kept their posts. The gallery and the terrace occupied most of the end of the arena where the races started.

A silence fell over the crowd as the armoured guards raised their standards. Cymbals clashed and trumpets sounded. The drawn curtains in the gallery suddenly parted, revealing the tall figure of Justinian in his purple robe, a colour no one else had the right to wear. On his head glittered a crown of precious jewels and on his right shoulder sparkled a cross rising from a circle which represented the earth.

To the people it was a breath-taking sight, a symbol of the empire’s wealth and majesty. They leaped to their feet and shouted the usual salute: “Long life to the Thrice August!”

Justinian took his seat on the throne chair and with a wave of his hand signaled for the races to begin.

The crowd leaned forward, watching the chariots break from the starting point. People cheered their favorites and clutched their good luck charms as the horses swung into the first turn. The chariots raced around and around the long central island of the racecourse where the shaft of a Pharaoh of Egypt rose above twisted bronze serpents. As the laps were completed, gilded balls dropped on the indicators at one end of the central island.

When the race was over, the crowd turned to their emperor again. Thrice August!” they shouted. “May you reign forever!” Then they expressed their wish. “Release the two who were hanged!”

After each race the cry went up again. “Thrice August! Release the two who were condemned by your prefect and yet spared by God.”

It was there in the Hippodrome that Justinian made his first serious mistake. He ignored the demands of his people. He preferred to leave local matters in the hands of Eudaemon.

The crowd lingered after the races. Their cries to the emperor had gone unanswered. The two in the church would be caught and hanged again. A terrible wrong was about to take place, mocking the will of God. Enemies of the emperor mingled with the people and pointed out that what Justinian had refused to do the people could do themselves. They led the multitude to the city government building and demanded the removal of the soldiers around the Church of St. Lawrence.

When they were turned away, they rushed to the church, killed the soldiers who tried to stop them and rescued the two men.

FIRE IN THE NIGHT

The taste of victory made them excited. They hurried back to the city building, released all the prisoners being held there and set the building on fire. They found carts of hay, set them ablaze and ran them against other buildings. Wind fanned the flames. During the night a large section of the city, including the senate house and the greatest of all the churches in Constantinople, the Hagia Sophia, went up in flames.

The next day Justinian ordered the races to continue as though nothing had happened. The people were no longer interested in races. They had new demands to make. They threatened to continue their rioting unless the emperor dismissed the unpopular John of Cappadocia, who had made their taxes so high and Eudaemon, who had charge of local affairs within the city. Restless crowds thronged the streets. Watchers on the roof of the palace reported to the emperor that people were fleeing from the city, some by bridge over the harbor, some by boat across the Bosporus to the shore of Asia. It was a bad sign. The people were expecting more violence.

By now most of the senators and high officials had sought refuge in the palace. They urged Justinian to bow to the wishes of the people by removing John of Cappadocia and Eudaemon from office. Justinian hesitated. Ever since his coronation in the Hagia Sophia church, he had been haunted by the fact that the western half of the empire had fallen into enemy hands. His shipping routes in the Mediterranean were constantly being threatened by enemy ships. Trade had suffered. Import duties had been reduced to only a small part of what they once had been. Taxes from the West, which rightfully belonged to the empire, were now collected by enemies.

TAXES FOR WAR

The empire, like an old man, was growing weaker and weaker, slowly dying; most of the generals and high government officials and senators seemed to be closing their eyes to what was happening. They were too interested in personal affairs. They seemed content to live for today, without any thought for the problems of the future.

Justinian had long dreamed of rebuilding the empire. Against the advice of his best generals, he had planned a military campaign to win back the lands in the west. He was building a fleet of ships for that purpose in the shipyards of the Golden Horn. He had recently recalled two of his favorite generals, Belisarius and Mundus, from their frontier posts on the eastern front and they and their troops were now quartered within the city. Waging war was expensive. New taxes had to be collected. John of Cappadocia had not only collected new taxes but had also launched a drive for less government spending. It was these actions which had made the man so unpopular.

The senators hated John for having dared to tax them. Justinian knew that he himself was not popular with the senators. There were so few people he could trust and John was one of them. Finally, although he hated to do it, Justinian agreed to follow the advice of the senators. He sent word to the people in the streets that he would dismiss the unpopular officials and appoint new ones in their place.

REVOLT IN THE STREETS

The news pleased the people in the streets, but they did not go home. They had discovered their Strength and their fear of Justinian had melted away. Senators unfriendly to the emperor sent their agents among the people to urge them to make bigger and greater demands. The agents pointed out that Justinian might not keep his promise after the mobs had disappeared from the streets. What they really needed was a new ruler. All through the night, messengers of hate sped from one mob to another urging them to revolt. At dawn the people broke into the city arsenal and armed themselves with weapons.

Narses, one of Justinian’s most trusted attendants, kept the emperor informed on what was happening in the streets. Justinian feared that the palace guard could no longer be trusted. He ordered his generals, Mundus and Belisarius, to bring their troops to the palace grounds.

For the next three days, armed mobs surrounded the palace. Justinian forced the senators and noblemen he could not trust to leave the palace. He sent his generals and their soldiers, numbering only fourteen hundred troops, to clear the streets. The people fought back. They threw stones and bricks at the soldiers from rooftops and set fire to buildings to force the soldiers back with smoke and flame. When the generals found that they did not have enough soldiers to clear the streets, they brought their troops back to the palace grounds.

“VICTORY! VICTORY!”

On Sunday morning, Justinian sent out messengers to announce that he would face the people in the Hippodrome that afternoon. At the appointed hour he made his way through the tunnel from the palace to the imperial gallery in the Hippodrome. Dressed in the purple robes of his office, with a book of the gospels in his hand, he told his imperial announcer to repeat his words to the people.

“Justinian, Imperator and Augustus . . . promises full mercy for all that has happened. No one . . will be held guilty or harmed . . . for what he has done. . .

Justinian held up the gospels and cried, “I alone am guilty. This I swear . . . upon these holy Evangels.”

A murmur ran through the crowd, but the leaders of the revolt were not going to be denied success when the battle was all but won.

“You are lying!” cried one of them.

Another cried, “How will you keep your word, Justinian?”

Their questions were enough to set off the crowd. The people leaped to their feet shouting in anger. Justinian tried to quiet them, but could not. He returned to the palace with the chant of the mob ringing in his cars, “Nike! Nike!””Victory! Victory!”

To the people in the Hippodrome it seemed clear that victory was at last within reach. Their forces were strengthened by armed bands of farm workers and hired fighters sent into the city by rich landowners. The leaders of the revolt gathered and held a council in the forum of Constantine. Senators who knew the weakness of the force guarding the palace urged that the palace be taken at once. A senator named Origen convinced them it would be better to wait, for he felt certain that Justinian and his wife Theodora would escape by boat from the palace dock. If so, no more fighting would be necessary.

The council decided that Hypatius, the nephew of an earlier ruler, should be the one to succeed Justinian on the throne. He was taken from his home against his will, brought before the forum and proclaimed emperor of the Romans. Then the leaders of the revolt took him to the Hippodrome. Somehow they found a purple robe for him and brought him out on the imperial balcony to present to the people.

JUSTINIAN’S ESCAPE

For some reason, the newly appointed emperor Hypatius sent a message to Justinian. As the messenger was entering the palace grounds, he bumped into an imperial secretary who was coming out. The secretary told him that Justinian and his wife were no longer at the palace. They had fled by boat a few minutes ago. This information was false, but the messenger did not know that. He ran back to give the new emperor the wonderful news. Soon everyone in the arena knew of Justinian’s escape and started a joyous chant: “Nika! Nika! Nika!”

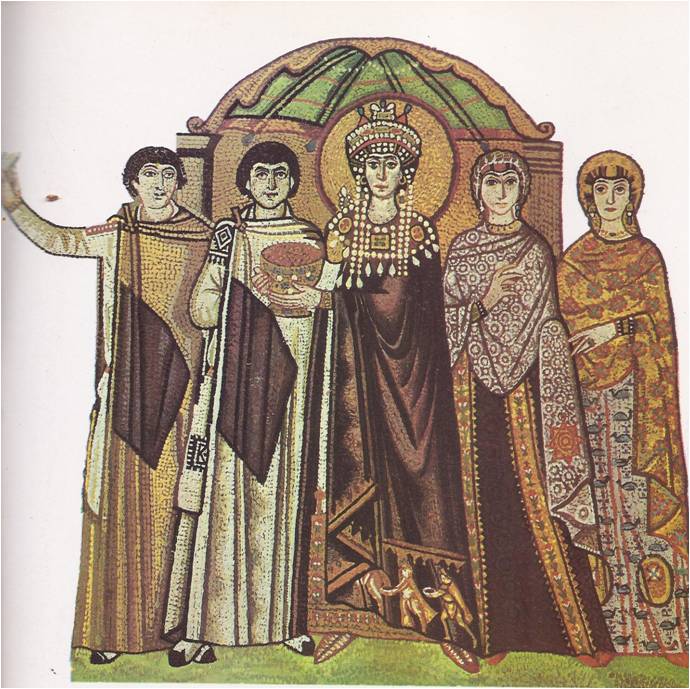

The chant could be heard in the council room of the royal palace, where Justinian and his trusted advisers were trying to decide what to do. Empress Theodora was present as well, but only as a listener. John of Cappadocia and Belisarius favored taking the gold treasure and sailing for Heracles. Since the imperial dock was on the place grounds, there would be little risk. In the event of attack, Belisarius’s troops could easily stand off the mob while the imperial party boarded the ship. Justinian listened in silence. He could not make up his mind.

Theodora suddenly rose to her feet and faced Justinian. It was against custom for a woman to speak in the council of men, but such rules were of little importance now. She told Justinian he could leave without trouble. The sea was there and the ship was waiting. He would have money enough to live well for the rest of his life. But she added, “I shall stay. I believe that those who put on the imperial purple must never put it off. The day that they cease to call me Augusta I hope I shall not be living.”

Her words were probably what Justinian needed most to hear. He did not try to change her mind, nor would he consider leaving her behind. If she stayed, so would all of them. Time was short. They had to act quickly lt was agreed that Mundus and his men would guard the gate. Belisarius would lead his troops through the emperor’s private tunnel to the Hippodrome and capture the leaders of the revolt in the imperial balcony.

All went well until Belisarius and his men reached the Ivory Gate at the far end of the tunnel. It was barred and he could not break through. He tried to reach the balcony through another entrance‚ only to find the door locked.

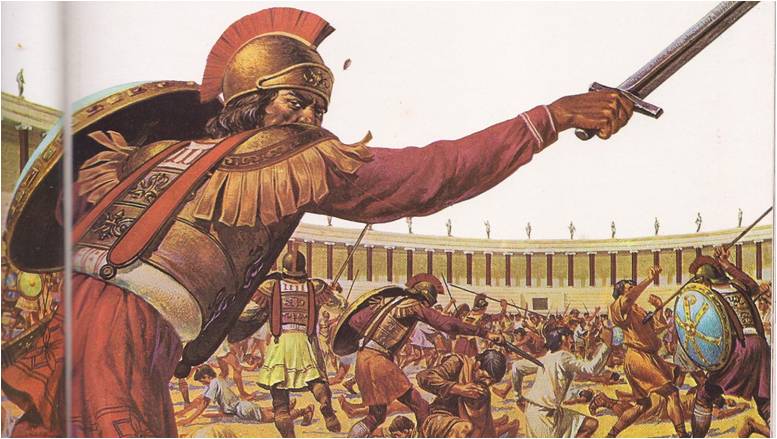

In the arena, the crowd caught sight of his soldiers moving into the stands. The people let out shrieks of anger and rushed at them. The highly trained soldiers in their glistening armour, the famous “iron cavalry” of Belisarius‚ knew how to meet a direct attack. The poorly armed masses were no match for the hell of arrows and the lightning thrusts of the soldiers’ javelins.

The slaughter did not stop the people. They came on and on, stepping over their wounded and dead. There were too many of them, and slowly the soldiers were pushed back and were being pinned against the wall. They were almost out of arrows when Mundus and his special troops, called Heruls, crashed through the Gate of Death on the far side. The powerful Heruls struck at the rear of the mob with their short, heavy hacking swords. Then Narses joined them with a small group of expert swordsmen from the palace.

THE GREAT MASSACRE

Many thousands were killed that afternoon in the blood-soaked arena before the revolt came to an end and word of the massacre quickly spread over the city. The streets cleared as people fled to their homes in panic. Hypatius‚ who only a few hours earlier had been hailed as the new emperor, was arrested. His body was fished out of the water several days later, but how he met his death is not known.

Having regained power, Justinian remembered the promise he made in the Hippodrome and treated his enemies with mercy. Even the senators who had plotted against him were finally forgiven. There was, however, a change in his feeling toward the senate itself. The senate in Constantinople had never had the standing of the one in Rome. It was made up of all officials past and present, above a certain rank and their descendants. The result was a strange mixture. Most of the senators were men of wealth, but some were not. All had power and influence and they were generally looked up to by the people.

The authority of the senate really rested on the fact that it was, by tradition, a recognized part of the empire’s government. Under the emperors of Byzantium, its authority depended mainly upon the personal attitude of each ruler. A weak emperor was always tempted to lean on the senate and to follow its advice in all important matters. In such times the senate became the most powerful authority in the empire. A strong emperor, on the other hand, usually had his own ideas about what should be done and rarely asked for advice from the senate. During the reign of a strong emperor, the senate usually had very little to do and was not very important.

After the Nika revolt, as the uprising was called, Justinian no longer trusted the senate. Never again did he ask it for help or advice of any kind. The business of running a great empire was too much for one man. Like most of the emperors before and after him, Justinian found it practical to turn over many of his problems to a small council of loyal officials. They met frequently in a special room set aside for them in the palace. They took care of money problems and dealt with treason, war and anything else that the emperor might put before them.

Justinian did not always follow their advice. When the council suggested that food and money be sent to Antioch after that city was destroyed by an earthquake, Justinian had a better idea. He rebuilt the entire city and provided it with great paved forums. Justinian was one of the greatest builders of all time. There was hardly a period in his long reign when he was not at work on some large building program. He built the great church of St. John at Ephesus, roads and bridges in Asia Minor and new monasteries at Nicaea. He changed the course of the Cydnus River to protect the city of Tarsus from floods.

A GREAT CATHEDRAL RISES

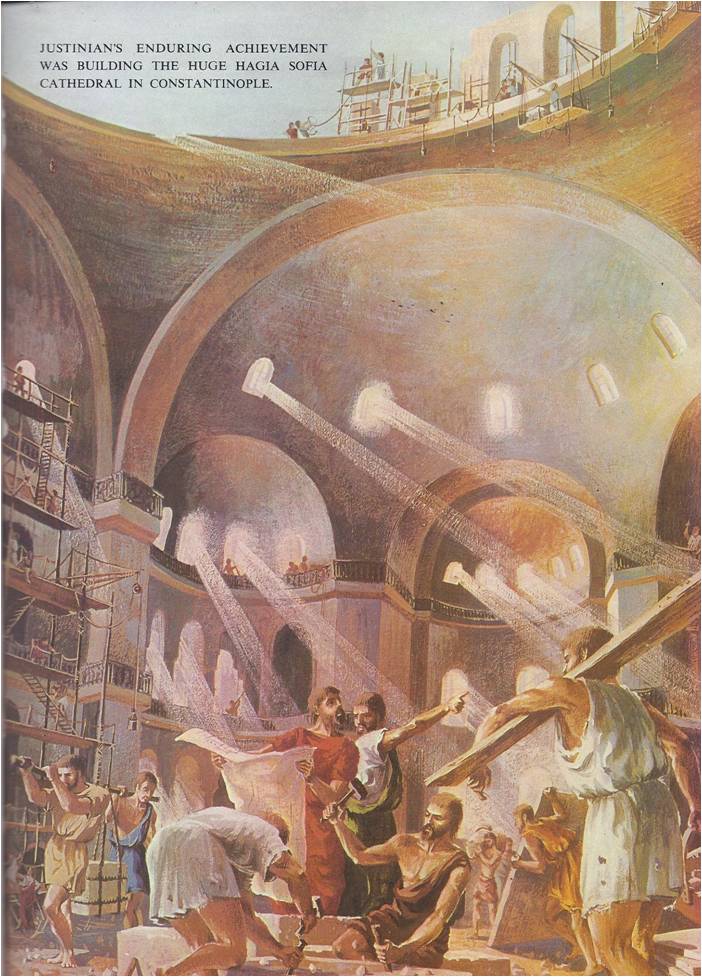

Cities everywhere in the empire benefited by his generous building programs, but Constantinople benefited most of all. There, on the ruins left by the fires of the Nika Revolt, he built a beautiful city. Instead of rebuilding the great church of Hagia Sophia, Justinian called in his best architects and told them to design a large cathedral. No wood was to be used. The building was to be fireproof, all stone and mortar, of a new design and at least as large as the great temples of the pharaohs. The Egyptian temples had flat roofs and rows of massive columns. The new cathedral was to have neither of these features. In the East, Christian Churches were usually six-sided, or shaped like a cross, with a small dome over the altar. Churches in Rome had arches and were usually rectangular in shape. Such churches had rows of columns running on each side along the length of the building and this type of church let in very little light.

The new cathedral would not be like any of the other churches. It would be flooded with sunlight from a great dome one hundred and sixty feet above the floor. The weight of the dome would rest on four arches supported by four piers. Could such a huge dome be constructed on a square base? It had never been attempted before on a large scale. The architects were uneasy because they were dealing with weights and strains that no one knew much about. They did know that ordinary cement would not be strong enough Justinian ordered his chemists to produce stronger cement and they finally invented one that fused with heat.

The engineers of the Arsenal thought Justinian was mad to attempt such a building. They warned him that the enormous weight of the dome would send it crashing to earth. Justinian went ahead with his plans. Marble from Thessaly had to be cut and polished and shipped to Constantinople. Onyx and jasper were ordered from islands of the Aegan and hard, purple-red stone called porphyry was ordered from Egypt. Skilled workmen were brought in from many eastern cities and nearly ten thousand laborers working in shifts under two hundred foremen began constructing the great cathedral Hagia Sophia.

Slowly the gigantic piers began to rise. Stonemasons lifted huge blocks into place, one after another, working under awnings when it rained and by the light of torches at night. The piers rose above the top of the Hippodrome and could be seen far out at sea. The architects watched anxiously, for they had never worked with such weights and pressures before. Molten lead was poured into the spaces between the stones to help carry the weight of the dome.

One day, vertical cracks appeared in two of the piers. Work was halted at once on the two ends of the lofty arch that was rising between them. People shook their heads. The engineers of the Arsenal had been right all along, they said. The piers would surely collapse, bringing death to those working on the arch. On the advice of his architects, Justinian ordered the arch to be completed to “see what would happen.” The stonemasons knew they were risking their lives, but for several anxious days the work continued. Slowly the great arch was brought to its summit from both sides and joined. In spite of the cracks in the piers the arch stood firm.

The huge dome was made of light, porous stone. The inner walls of the church were lined with polished marble of many colors: black, red, yellow, green and purple. The four towering columns were made of polished porphyry and green granite called verd antique. Through windows along the outer rim of the dome, sunlight flooded the marble walls and reflected back to light up some four acres of gold-leaf mosaic on the vaulted ceilings. The new architectural style had clean lines and simplicity giving the cathedral an airy feeling of space and height. Gone were the carvings and niches and busts and statues that usually cluttered the buildings of Rome.

When Justinian dedicated the finished cathedral in 537, he raised his hands and cried, “Glory to God, who has judged me worthy of accomplishing such a work as this! 0 Solomon, I have outdone you!”

The Hagia Sophia, which came to be called St. Sophia, served as the religious center of Byzantium until the fall of the empire to the Turks nine hundred years later. It was the home church of the patriarch of Constantinople. There emperors were crowned and there emperors came to give thanks for their victories in battle. St. Sophia was a landmark in the history of architecture. It still stands today after hundreds of earthquakes and fourteen hundred years of constant use, which makes it older than any other great building in Christendom.

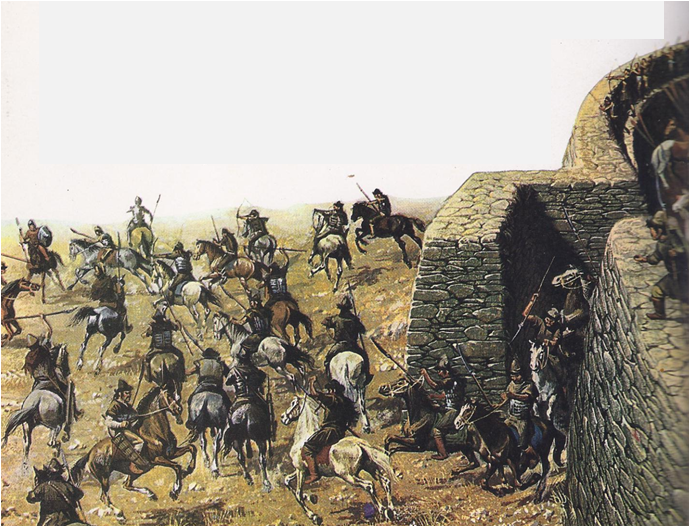

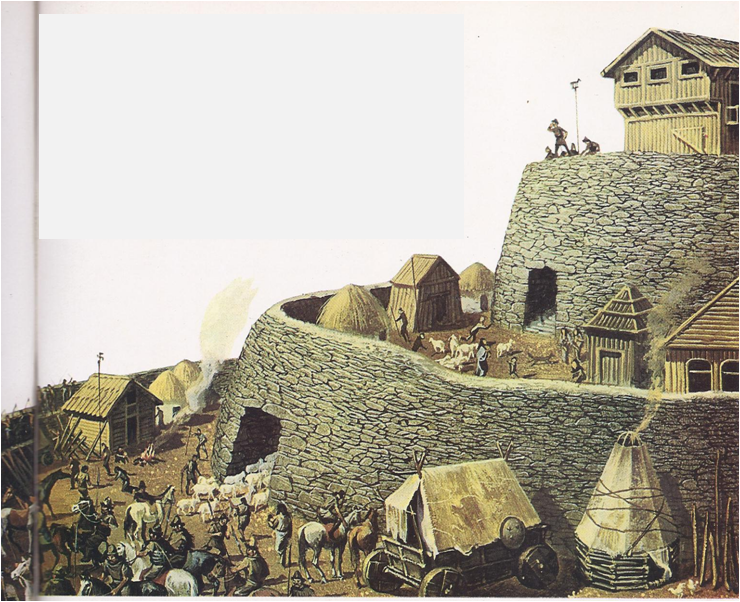

Another of Justinian‘s great building projects was his system of forts along the eastern borders. Procopius, a historian of that time, described how this system of forts came to be built:

“Wishing to defend the line of the Danube, Justinian bordered the river with numerous fortresses and set up guard-posts along the bank to prevent the barbarians from crossing. When these structures were completed he reflected that should the enemy succeed in penetrating this barrier they would find themselves among defenseless inhabitants, whom they could carry off into slavery unhindered, having sacked their estates. He was not content, therefore, to ensure a general measure of safety by means of the river forts alone, but constructed great numbers of other defense-works all over the flat country, until every manor was either transformed into a fortress or was protected by a nearby fortified position.”

Justinian connected these forts with a vast network of roads, some of which are still in use today. According to Procopius, Justinian’s forts saved the empire.

THE JUSTINIAN CODE

One of Justinian’s most outstanding projects was his Justinian Code. Justinian was interested in law and he spent many of his evenings reading laws made by other emperors. Many of these laws were very old, a number were no longer needed and others seemed foolish. Justinian thought there were far too many laws. It would have taken him years to read them all. To make things worse, not all the laws were kept in the same place. Some were stored away where few could find them. There was such a confusion of laws that no one could be certain what the law was on any particular subject. Justinian asked his legal expert, Tribonian, to work out a better and simpler system of laws.

Tribonian suggested that they make a fresh start by picking out the laws that were still needed and doing away with the others. Then the necessary laws could be arranged in orderly fashion and published as a code representing the law of the land. This code would be called the Carpus Juris — the body of the law. Justinian gave Tribonian ten legal assistants and told him to complete the work in one year and out of this effort came the famous Justinian Code. With a few changes now and then, it remained the basic law of the land throughout its history. Centuries later when the printing press had been invented, copies of the code were widely published in Europe and influenced most lawmakers.

During his long reign of almost forty years, Justinian carried on a series of military campaigns to recapture the West. He won back Africa, Italy, a part of Spain and various islands. He made the Frankish kings of Gaul recognize his sovereignty and the Mediterranean was once again a Roman sea. His efforts in the West weakened his eastern front and led to Persian invasions and the destruction of the city of Antioch.

Justinian’s reign was the most brilliant and glorious in Byzantine history. By the time of his death in 565, the empire was so exhausted that it was150 years before it recovered its strength.