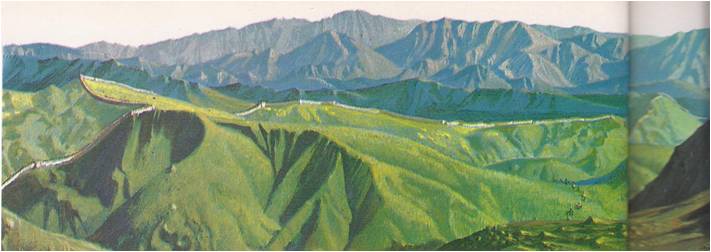

THE vast East Asian land of China is named after its first family of emperors, the Ch’in. The Ch’in brought the country together under one government and built the Great Wall to keep out northern barbarians. They were in such a hurry to get things done, however, that they drove their subjects too hard and lost their support. In 206 B.C., after only a few years in power, they were overthrown.

The Ch’in were replaced by an imperial family named Han. The Han dynasty ruled for two centuries before the time of Christ and then, after a break, for another two centuries. These two periods are called the Former Han and the Later Han. By the time the Han finally fell from power, the Chinese people all spoke the same language and used the same “idea-pictures,” made with brush-strokes, in writing. They had truly become a nation. To this day their descendants call themselves “men of Han.”

The Former Han emperors took power away from rich landowners and gave it to officials who had passed difficult examinations in the teachings of Confucius, the great Chinese thinker and religious teacher. Their armies checked many attacks by wild herdsmen-warriors known as the Hsiung Nu, or Huns. As trade flourished, so did the painting of pictures, the composing of poems and the study of the classic Chinese writings of the past.

Toward the end of their reign, however, the Former Han emperors had to surrender more and more power to the wealthy noblemen who owned the country’s richest farmlands. In A.D.8, a man named Wang Mang seized control of the empire. Although he was a nobleman himself, he set out to reform the unfair tax system which allowed aristocratic landowners to grow rich at the expense of the peasants and the government. He ordered the landowners to divide their estates among the peasants who farmed them. Rather than obey, the landowners rebelled. In A.D. 23, they killed Wang Mang and put a member of the Han family back on the imperial throne.

TRADE AND NEW IDEAS

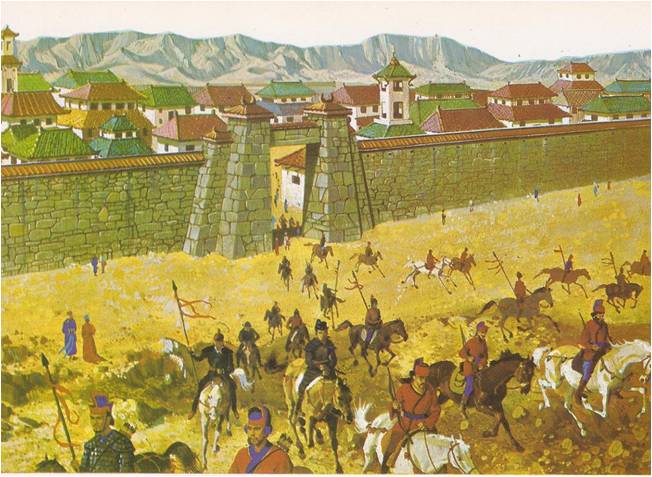

The restored Han government began strongly. By the year 100, its armies had conquered Central Asia all the way west to the Caspian Sea. This brought the Han Empire to within only a few hundred miles of the Roman Empire. With Chinese soldiers patrolling the roads that crossed the vast, mountainous interior of the continent, the merchants of China could send heavily-laden caravans to west China and Europe, knowing that their goods would arrive safer. In the cities of the Roman Empire, silks and other Chinese products fetched high prices. And the products of craftsmen in those cities were brought back for sale in the markets of China.

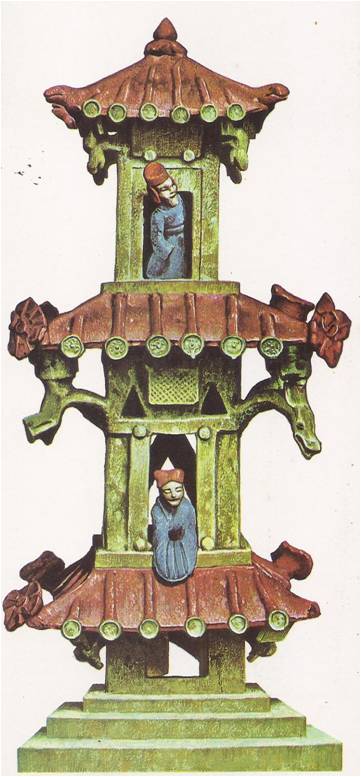

Along with foreign goods came foreign ideas — including, particularly, the Buddhist religion from India. These new ideas stimulated Chinese thought. About 105, the Chinese invented paper. Paper was much more convenient than clumsy slips of wood or bamboo and much cheaper than Silk. It helped to spread ideas and speeded the growth of Chinese civilization. After paper, the next great Chinese invention was porcelain, which was later to develop into the fine chinaware admired all over the world.

Like the Former Han emperors, the emperors of the Later Han tried to create a strong, unified government. Certain evils in the accepted way of doing things made their task difficult. These evils were the same ones that had brought down the Former Han. Fundamentally, they had to do with money. In one form or another, they were to plague all Chinese governments until very recent times.

By custom, the landowners collected half of their peasants’ crops as rent, but the land tax they paid the government was only about one-thirtieth of the value of these crops. Taking in so much and paying out so little, they grew richer all the time. Since their land taxes never covered the cost of running the country, the government taxed the free, landowning peasants as well. When the government’s expenses grew heavier, so did the free peasants’ taxes, especially in North China, where a large army had to be stationed in case the Huns invaded. At last the free peasants could no longer pay their taxes and still have enough left over to eat. Some fled to the rice-growing regions of the Yangtze River and South China, where taxes were lower. Others fled to the big estates. Still others, in desperation, became outlaws.

By 184, two serious peasant rebellions had broken out. The rebels in East China were called the Yellow Turbans after the kerchiefs of yellow they wore around their necks. Yellow stood for “earth,” which the rebels hoped would snuff out the red “fire” that stood for the hated Han rule. The rebels of Szechwan, in west China, were called the Five-Pecks-of-Rice Band after the dues each member had to pay.

In putting down these revolts, the top generals of the imperial army gained so much power that they became the real rulers of China. By 221 the country was split into three kingdoms, and the great Han Empire was no more.