Go-Daigo had found refuge in a place in the mountains called Yoshino. Japan now had two emperors, one in Kyoto and the other in Yoshino. Takauji set out to simplify matters. As a first step, he had his puppet, the Kyoto emperor, appoint him shogun.

In this way, Takauji became the founder of a new line of shoguns who were called, after their family name, the Ashikaga shoguns. Their shogunate lasted from 1336 to 1573, nearly twice as long as the Kamakura shogunate. Takauji and his successors did not rule anywhere near as firmly as Yorimoto and the Hojo family. They never controlled all of Japan or even much of it. Most of the time, they could not even keep order in the areas they supposedly did control.

The Ashikaga shogunate went through three stages. The first stage, from 1136 to 1392, was marked by constant fighting between supporters of the rival emperors. It ended when the shogun lured the Yoshino emperor to Kyoto by promising to let his branch of the imperial family take turns with the other branch on the throne. The Ashikagas broke their promise, for no descendant of Go-Daigo ever became emperor. At least Japan had only one emperor.

The middle stage of the shogunate, from 1392 to 1467, was the only time when the Ashikagas really seemed to rule. The last stage, from 1467 to 1573, was disastrous for the family. It began with a ruinous war between two groups of power-hungry warlords. In the fighting, Kyoto was devastated and the shogunate was finished as a force in government. The shoguns hung on to their post for another century, mainly because no one bothered to take it from them. When the last Ashikaga shogun was stripped of his title in 1573, the shogun had become so unimportant that hardly anybody noticed or cared.

So the Ashikagas themselves did not play leading roles in the two and a half centuries of Japanese history that bear their name. Instead, these roles were played by a group of assorted warlords, pirates, merchants, Buddhist monks, architects, actors and others. It was an exciting time, with a great many things going on.

The warlords had replaced the warriors as the dominant class in Japan and it was their greed for land that caused most of the fighting. In these wars the mounted knights who had been the pride of the Kamakura shogunate became less important than foot soldiers. No longer was it the samurai’s sword that decided the outcome of a battle. Victory usually went to the warlord who commanded the most troops.

THE WARLORDS

Like the knights of Europe, the samurai of Japan were aristocrats. The soldiers, on the other hand, were ordinary men. The warlords needed them to fight, the ordinary people of Japan began for the first time to have some say in affairs. The confusion of the times also made it easier for men to rise from the bottom, particularly if they were skilled fighters and natural leaders. Often soldiers rebelled against their lords and took over their lands. Once in command, the rebel chiefs took new names and pretended they belonged to a forgotten branch of some great noble family. The warlords were greedy for wealth and they saw that big profits could be made from trading with China. The trouble was that the Chinese considered foreign trade undesirable and refused to do business. The warlords’ answer to that was piracy. They kept little navies in the East China Sea. When their sailors spied a Chinese junk, they would make her stop and then screaming and waving their swords, they would climb aboard her. Sometimes they were after loot, but more often they were trying to frighten the Chinese captain and crew into heading for their master’s port so that he could trade with them.

During the Ashikaga Period, the headquarters of the estates often became villages and many villages grew into towns. Before then, towns had grown up only at centres of government, but these new towns came into being to meet the needs of war, trade, or religion. “Castle towns” developed around the strongholds of warlords, and “trade towns” at ports, highway junctions, and market places. “Temple towns” rose in the vicinity of the larger Buddhist temples.

ZEN BUDDHISM

Buddhism enjoyed a great revival in Ashikaga times. The most popular forms of the religion were those preached by the Pure Land Sect and the True Sect. A third sect, which appealed most to thoughtful people, was called Zen.

Zen Buddhism, brought from China by monks, was something like Taoism. It taught its followers to seek wisdom by firmly controlling their minds and bodies. Unlike the monks of some other sects, Zen monks did not pass their lives in meditating or even in preaching. They were active in all sorts of practical fields. Throughout the Ashikaga Period they were the leading traders with China and they built many beautiful monasteries and temples out of their profits. Many Zen monks were industrious scholars, while others were gifted writers and artists. Certain key features of their faith — its emphasis on nature, for instance — made it especially appealing to the Japanese. The influence of Zen Buddhism on Japanese thought and taste became so overwhelming that the Ashikaga Period could be called an age of Zen culture. That culture produced most of Japan’s original contributions to the world, including the tea ceremony, Flower-arranging, Japanese landscape gardening and architecture, the tokonoma, and the No drama.

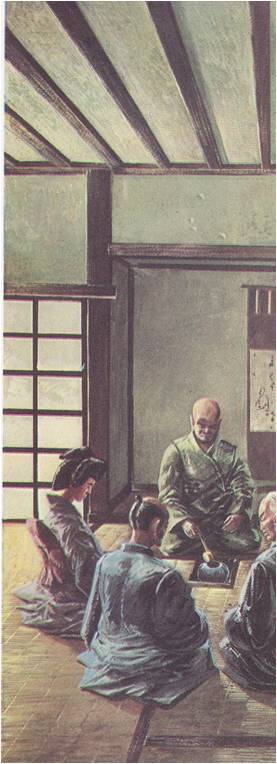

In Ashikaga Japan, the tea ceremony was a kind of acting-out of the Zen spirit. A small group of art-lovers would gather in a bare, simple room close to the beauties of nature. Tea was brewed and served in slow, almost rhythmic movements. After everyone had sipped from a common bowl, the company passed the time discussing the bowl and the other implements that had been used.

Japanese love of nature and Zen ideas of form together made landscape gardening a fine art. Often, the trees, ponds, bushes, and stones around a building became more important than the building itself. Architecture moved closer to the modern Japanese style, practical yet pleasing to the eye. Inside Japanese houses, thick rush mats now covered the entire floor of a room instead of only a part of it. The tokonoma‚ previously a shrine-like alcove in the main room, became what it has been ever since: a place for something beautiful, such as a painting a piece of porcelain, or an arrangement of flowers.

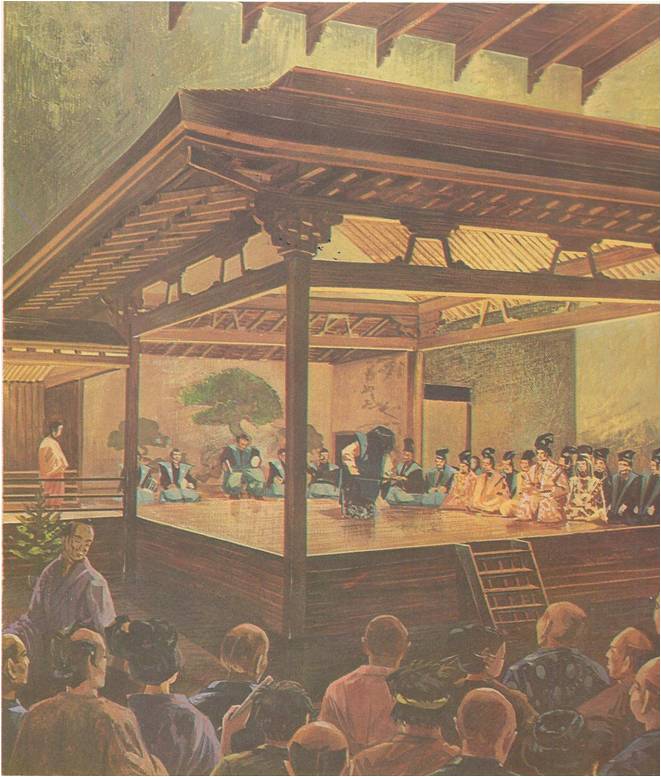

THE NO DRAMA

The most original literary development of Ashikaga times was the No drama. No plays were performed on a bare stage against a backdrop showing a pine tree. The actors wore elaborate costumes and masks. A chorus helped to explain the story and actors and chorus chanted their lines to the music of a small orchestra.

Cultural activity centered around Kyoto, and it was interrupted by the war which started the third stage of the Ashikaga shogunate. When the fighting moved away from the capital, cultural activity began again. Meanwhile, the imperial court had been dealt a blow from which it would not recover for centuries. The private estates from which the emperor and his courtiers drew their incomes had been seized by the fighting warlords. During the last half of the fifteenth century and the first half of the sixteenth, the court was just about bankrupt. It could no longer afford to support retired emperors, so emperors had to stay on the throne until they died. One emperor even had to sell examples of his beautiful handwriting for a living.

Outside Kyoto, the fighting among the warlords continued for a century of the fiercest combat Japan had ever known. As strong warlords defeated weaker ones, their lands and armies grew larger. At last the holdings of the few remaining warlords were so big that they were really small kingdoms. It was only a question of time until the most powerful warlord would conquer the others and unite the country.

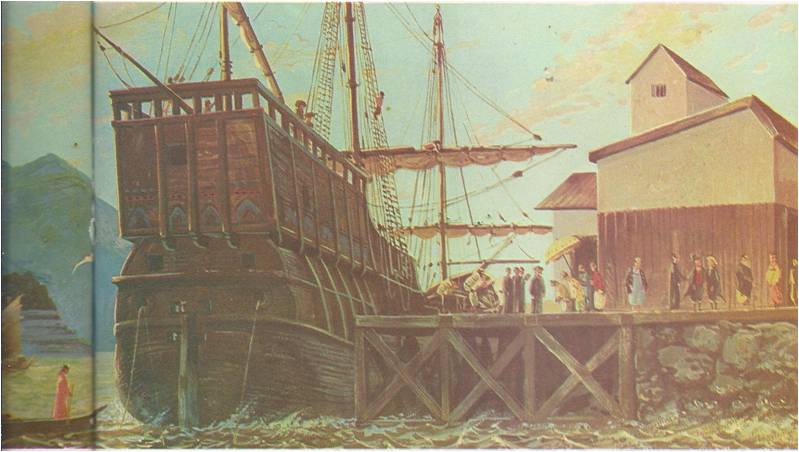

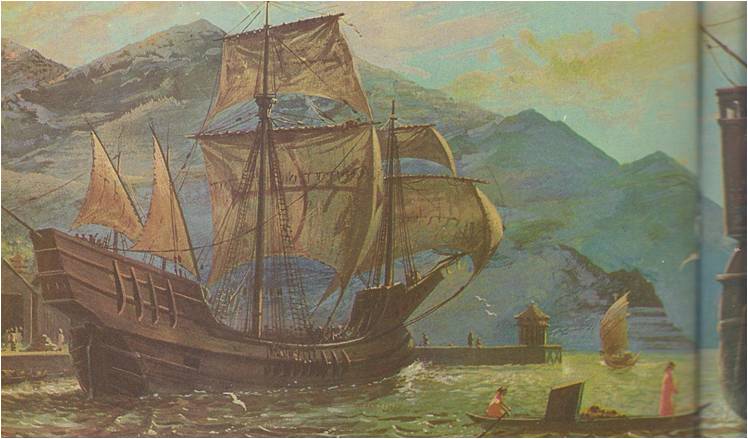

Then, in 1543, Portuguese traders and missionaries arrived in Kyushu. The Portuguese had not thought much of the Asian peoples they had met so far, but they liked the Japanese from the start. Both the Japanese and the Portuguese were full of national pride, both believed in a medieval code of honour — and both wanted to do business.

CHRISTIAN CONVERTS

So eager for trade were the warlords of Kyushu that more than one became a Christian and forced his subjects to do the same in the hope of luring the Portuguese ships into his ports. In addition, large numbers of Japanese were sincerely converted, although some of them at first mistook Christianity for a new kind of Buddhism. Along with enthusiasm for the newcomers’ religion went a craze for everything Portuguese. The more daring Japanese dandies even were clothes copied from the dress of Portuguese sailors. Many Portuguese words came into use, including a few, such as pan for “bread,” which are still part of the language.

The success of the Christian missionaries made the Buddhist leaders jealous. Soon the warlords began to see that the Europeans, with their heavily armed warships, might easily threaten their own wealth, power and position. They began to persecute both Japanese Christians and European missionaries and by 1641, they had driven the last of the European traders from Japan. The “source of the sun” went into a long eclipse. Japan was to stay cut off from the rest of the world for the next two hundred years.