THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION created a republic of thirteen states, the first large republic in history. The nation was to be ruled, not by a single man or group of men, but by the people themselves. The whole world watched the American experiment. After all, fighting a revolution and setting up a republic was one thing; making it work was another. Would the people have enough intelligence and strength of will to obey laws they had made themselves?

The monarchs and aristocrats of Europe smiled, sure that they knew the answer. Why, the very idea of a republic was a joke! People were too stupid and selfish to govern themselves. Before long, the United States would become a kingdom or a dictatorship.

Indeed, for a while it seemed as though the kings and aristocrats would be proved right. Under the Articles of Confederation, the central government of the United States had no power to speak of. It could not tax, or regulate trade, or enforce the law and each of the thirteen states could do as it pleased. Many Americans, including the leaders of the revolution, began to realize that the liberties they had fought for were in danger. If the thirteen states were not brought together under one set of laws and one strong central government, they would break up into separate little states and they might easily fall to someone who set himself up as a king or military dictator.

The leaders of the Revolution — George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Alexander Hamilton and others — agreed that the Articles of Confederation were too weak and that something had to be done. Thanks to their efforts, a convention was held in Philadelphia in 1787. All the states sent delegates, who soon came to the conclusion that the Articles of Confederation were not worth saving. They made a completely new start and drew up what has been recognized as one of the most remarkable documents in world history — the Constitution of the United States.

The constitution created a strong central government leaving the states with the power to settle local problems. It was up to the states to set up their own schools, local courts and to give police protection. They had to build bridges, roads and canals. Each state could decide for itself which of its citizens should be given the right to vote. No states could give out titles of nobility, make treaties with other countries or wage war.

The national government was given the power to collect taxes, to borrow money and also to make its own money. It could regulate trade between the states, with other countries and collect import taxes on products brought in from foreign countries. it was expected to provide mail service, build up an army and navy when necessary, and construct military roads and bridges. It was to deal with foreign governments and with the Indians. It was given control of public lands and could create new states which would be equal in every way with the thirteen original states.

CHECKS AND BALANCES

The power of the new government was divided among three branches: the courts, known as the judiciary branch; Congress, the law-making or legislative branch; and the President and the officers under him, the executive branch.

Each branch was meant to be equal and independent and yet provide checks and balances to prevent the other branches from taking more than their share of power. Thus the President had some control over the bills passed by Congress; he had to approve them before they became law. If he refused to sign a bill, it would not become law unless Congress passed it again by a two-thirds vote. The President also appointed judges for the courts, which allowed him to choose judges who shared his point of view on many questions of public importance. Such appointments had to be made with the approval of the Senate. Once the judges were appointed, they became independent of the other branches of the government.

Congress itself was divided into two houses, each to act as a balance on the other. One was the House of Representatives, whose members were elected by the people every two years. Members of the other house, the Senate, were chosen for six-year terms by the state legislatures.

Each state was represented by two senators and by one or more representatives, depending upon the population of the state. The president was to be elected by a College of Electors in a manner to be decided by state legislatures.

When the Constitution was finally adopted by the states in 1789, the United States became the most democratic nation on earth. Even so, the new government did not truly represent all the people, for in some states only property owners were allowed to vote. Liberty and equality and justice were generally recognized as the Godgiven rights of all men and yet most Negroes were still held in slavery.

No one was completely happy with the new constitution. Some farmers, tradesmen and labourers complained that it was not democratic enough because many of them had no vote and therefore no voice in the government. Wealthy merchants, shippers and bankers, on the other hand, complained that the federal government did not give them or their property enough protection.

Shortly after the Constitution became law, Thomas Jefferson wrote that the American people are “naturally divided into two parties: 1. Those who fear and distrust the people and wish to draw all powers from them into the hands of the higher classes. 2. Those who identify themselves with the people, have confidence in them . . . and consider them as the most honest and most safe . . . depository of the public interests. In every country these two parties exist and in every one where they are free to think, speak and write, they will declare themselves.”

Jefferson belonged to the group that believed in the people. He became one of the great leaders of the new nation and his followers became known as Jeffersonians, or Democratic-Republicans. The men who wanted to entrust the government to the upper classes formed a group known as the Federalist party and their leader was Alexander Hamilton.

Oddly enough, both Hamilton and Jefferson served in George Washington’s cabinet. Jefferson was Secretary of State, while Hamilton was Secretary of the Treasury. Washington, who had the support of both Jeffersonians and Federalists, tried not to take sides between them. As Secretary of the Treasury, Hamilton faced the problem of the national debt. During the revolution, the United States had borrowed large sums of money from foreign governments and private individuals. Hamilton felt that the debt should be the responsibility of the national government. His method of paying it worked out to bring the most benefit to the owners of property, mainly industrialists and bankers. Hamilton believed that a strong central government under the control of men of property would give the nation the best rule.

In 1791, Congress approved his plan for paying off the debt. Hamilton set up the Bank of the United States and a national mint for the making of coins. The Bank of the United States brought the property owners and the government closer together. Hamilton was also able to get Congress to pass laws placing a tax on manufactured goods imported from other countries and a tax on the making of whiskey and other liquors. The import tax pleased American manufacturers who could now sell their products at prices lower than those asked for goods shipped in from Europe. Whiskey was made by small farmers and they were not all pleased by the new tax. Most of them lived in distant areas with poor roads. They could not always haul their grain to market as soon as it was harvested and to stop it from spoiling, they made it into whiskey. Later, in better weather, they hauled the whiskey to market and sold it.

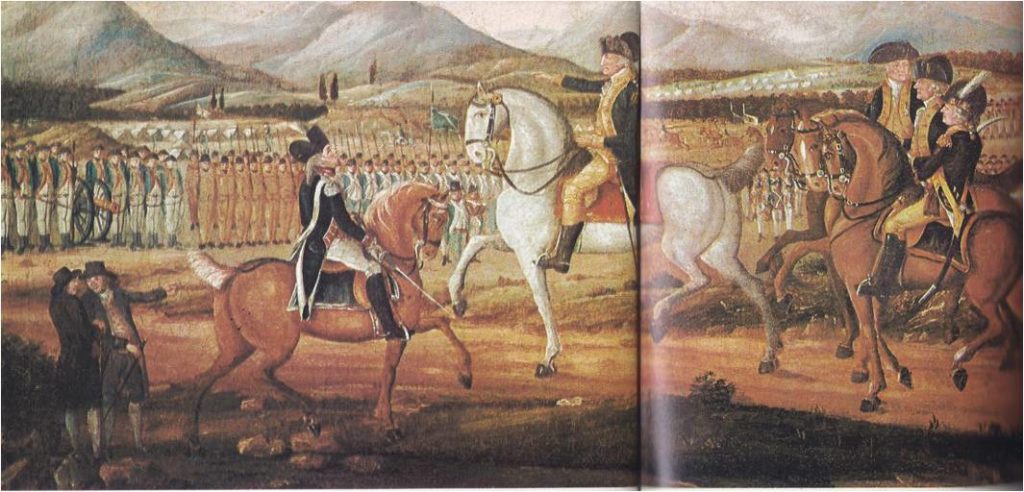

A number of farmers in western Pennsylvania flatly refused to pay the tax. President Washington sent in troops to put down this “Whiskey Rebellion” and made several arrests. This action established the authority of the government, but at the same time it made some Americans suspicious of it.

THE FEDERALISTS

Jefferson had been against the whiskey tax from the beginning. He argued that, like most of the laws passed at the suggestion of Hamilton, this one favoured wealthy property owners at the expense of ordinary Americans. Although Hamilton and the Federalists had largely been responsible for getting the Constitution adopted‚ Jefferson felt that they were now betraying it, and that liberty was being destroyed. Many Americas-unskilled labourers, small farmers, small businessmen — felt as Jefferson did, but they were widely scattered and unorganized. To bring them together and save republicanism, Jefferson urged the formation of a new political party and neighbourhood clubs known as Democratic Societies were organized in many communities. They held debates, gave lectures and discussed the important questions of the day. They encouraged men of their beliefs to organize and to support republican candidates for election. Out of all this activity grew the Democratic-Republican party, but in 1796 it was not yet strong enough to elect Jefferson to the Presidency. Instead, John Adams, a Federalist, became President.

“MILLIONS FOR DEFENSE”

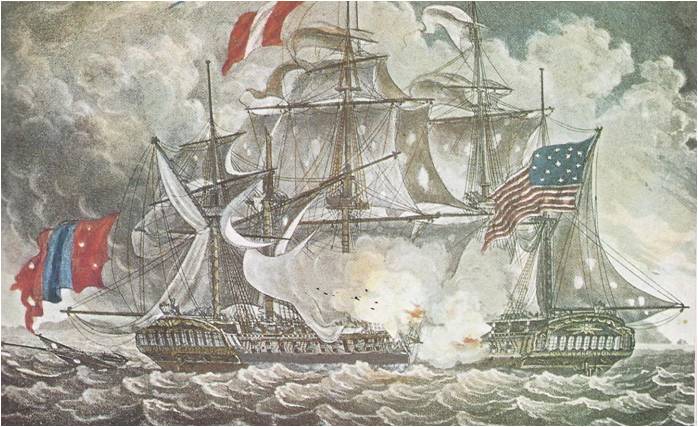

The French revolution also caused problems. The British king and other monarchs of Europe were at war with France, hoping to crush the revolution and restore the king to the throne. Most Americans were in sympathy with the French revolution. To many of the men who supported Adams, peace with England was essential to continued trade and to the nation’s prosperity and they tried to turn Adams against the French.

The French knew the Federalists supported the British and they refused to receive the minister Adams sent to France. More important, they began to sink American ships trading with the British. The Federalists, finding that they had an excuse to attack France, declared that the United States must take steps to defend its ships. Still trying to keep peace, Adams sent a special commission to Paris, but when it failed to accomplish anything, he told Congress that the nation had no choice but to prepare for war.

The Federalists stirred up feeling against France. They let it be known that French agents had secretly demanded that the special commission pay them bribe money and arrange a loan for France. The people of the United States were shocked and they cheered the slogan: “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute.”

This led to a naval war with France and during the two and one half years’ of war, the United States built up a standing army. Those Federalists who wanted war with France were delighted; besides, they were in power and could probably use the army for their political advantage. They were even more pleased when Hamilton was appointed second in command to Washington, who was old and ill.

Even so, the Democratic-Republicans continued to gain strength. The Federalists tried to turn public opinion against the Democratic-Republicans by telling lies about them. They insulted all people who spoke with a foreign accent, particularly the French and Irish, most of whom were followers of Jefferson. The Democratic-Republicans struck back with lies of their own and their newspapers carried on a campaign against the Federalists that was extremely bitter and often scandalous.

While feelings ran high on both sides, the Federalists in Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, hoping to strengthen the Federalists and weaken the Democratic-Republicans. One of these acts required that foreign-born persons had to live in the United States fourteen years before they could become citizens and vote. Under an earlier law, the required time had been only five years. Thus thousands of people who would probably have voted for Jeffersonian candidates were prevented from doing so. Another act gave the president the power to send foreigners back to their native land if he considered them dangerous to the United States. Although a Federalist, President Adams had not asked for this law and never used it. The Sedition Act seriously threatened the Bill of Rights of the Constitution and even the America form of representative government. It said, in effect that it was a crime for anyone to criticize the government or any office holder in the government.

Among the army Democrat-Rebuplicans who were arrested under the Sedition Act was the representative of Vermont, Matthew Lyon. His crime was that he had written a letter in which he criticized President Adams. He ran for Congress again while still in jail and was re-elected by a large majority. Others arrested were editors, printers and ministers of the Gospel. Whether the charges against them were true or false did not matter, for the judges were Federalists and most of them saw to it that their juries were made up only of Federalists. Angry crowds gathered whenever Democratic-Republicans were arrested and many meetings were held to complain about the new laws. Party members guarded the homes of leading Democratic-Republicans and the printing presses of newspapers.

JEFFERSON’S VICTORY

Public opinion began to turn against the Federalists, who found they could not depend upon local police to enforce the Alien and Sedition Acts. The new standing army was under their control and they used it to make arrests and break up crowds of angry citizens. Soldiers off duty were encouraged to raid and loot the homes of important Democratic-Republicans and to smash the printing presses of liberal newspapers. Many soldiers deserted and the army became so unpopular that it was almost impossible to hire new recruits.

Leading the fight against the Alien and Sedition Acts, Jefferson charged that they were an attempt by the Federalists to destroy freedom of speech and of the press. Since these rights belonged to the people under the Constitution, the acts were illegal and need not be enforced by the states. Jefferson continued the fight during the election campaign of 1800. By that time, President Adams, who had never wanted war with France, had acted to calm down the war fever, and France and the United States were attempting to settle their differences peaceably. Thus the

American votes were given a clear-cut choice between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The future of the country seemed to be at stake. If the Federalists won, they would have enough support to enforce the Alien and Sedition Acts strictly. They might then be able to pass other acts taking away the rights and powers of the people and their opponents charged, so destroy the Constitution of the United States.

When the election was held in 1800, John Adams failed to win a second term in office. The two republican candidates, Jefferson and Aaron Burr, each received seventy-three electoral votes. Such ties, according to the Constitution, had to be broken by the House of Representatives. Although Hamilton and Jefferson were political enemies, Hamilton had such a low opinion of Aaron Burr that he used his influence in the Congress to give Jefferson the election.

Jefferson’s victory in the 1801 election was, therefore, a decisive victory for American democracy; it made certain that the Federal government would belong to the people and not to a small privileged group. While Europe fell under the dictatorial rule of Napoleon, the United States returned to the original ideals of its revolution as expressed in the Bill of Rights. Once again, as in l776‚it was the hope of all men who longed for freedom.