On May 17, 1954, all was quiet and solemn, as it usually is, in the chambers of the United States Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. on that day the Court handed down a decision in the case of Brown versus the Board of Education of Topeka — a decision that burst on the United States like a clap of thunder on a fair day.

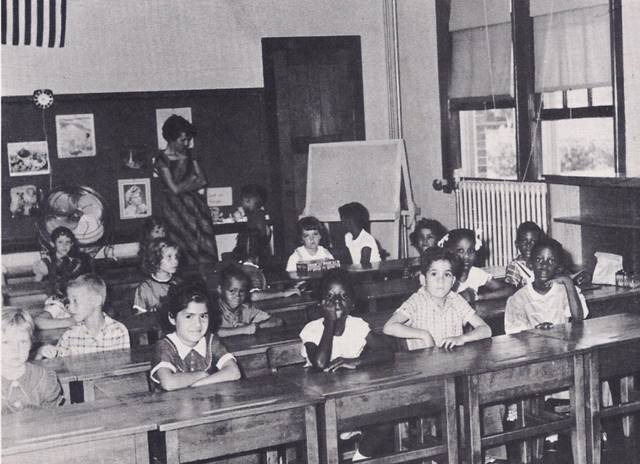

Brown was the name of the man who represented the Negroes of Topeka, Kansas. They charged that Topeka’s board of education had violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which says, “No state shall…. deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The Negroes of Topeka argued that the board of education was denying them “the equal protection of the laws” by assigning their children to separate Negro schools. These schools, they maintained, were inferior to the schools attended by white children. The Supreme Court agreed and ordered the board of education to integrate its schools.

The decision had an effect that went far beyond Topeka. It re-interpreted the Constitution, giving new meaning to the law of the land. It did away with a ruling made in 1896, which had allowed the states to segregate public places and in general, to do as they pleased about civil rights. At that time, the Court said that “equal protection of the laws” could also mean “separate but equal protection of the laws,” thus officially approving segregation. The “Jim Crow” laws passed in the South, the Southwest and even parts of the North, excluded Negroes from places used by whites, while other laws prevented them from voting. The result was that by the early twentieth century most Negroes in the United States had become second-class citizens.

Although the case of Brown versus the Board of Education dealt only with schools, the decision attacked the principle on which all forms of segregation was based. The Court was saying, in effect, that Negroes were equal with other citizens under the Constitution and that the federal government, not the states or local communities, was responsible for protecting their rights.

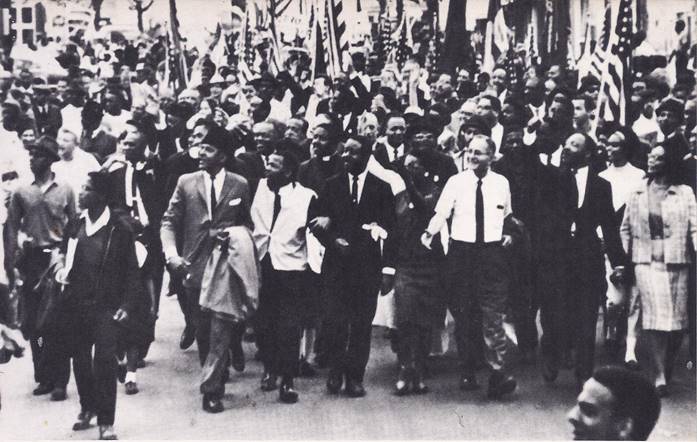

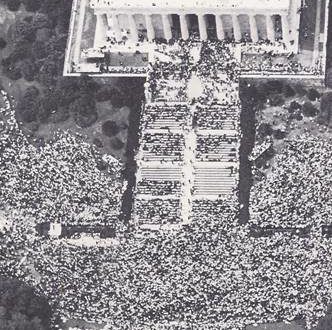

The decision gave enormous encouragement to Negroes to organize and act in their own behalf. The National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People had been fighting for civil rights for some time and new leaders and new movements, such as the Congress of Racial Equality‚ the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, sprang up, especially in the south. Among the new leaders was the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., a young Baptist minister from Atlanta. He preached the doctrine of non-violent resistance to segregation and in 1956 he led the Negro bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. The success of the boycott in ending bus segregation proved to Negroes everywhere that non-violent resistance could bring rapid results.

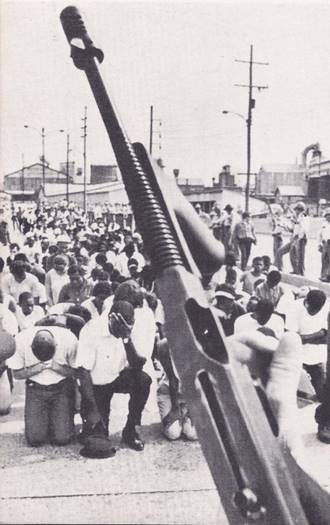

The civil rights movement scored further victories in 1961 and 1962. Southern Negroes conducted “sit-ins” in a number of cities, occupying seats at lunch counters until they were served or arrested. Later, “freedom rides” were carried out to integrate bus and train terminals. As Negro demonstrations grew in size and boldness, they met with opposition from Southern segregationists and in May of 1963 violence broke out in Birmingham, Alabama. Police opened up fire hoses and set dogs on a crowd of Negroes that had gathered for a protest march.

Many Americans were shocked by the police action and President Kennedy urged the Birmingham authorities to hold talks with the leaders of the Negro community. They did as he asked and reached an agreement on May 9. Under its terms, the city would hire Negroes without discrimination and a panel of prominent Negroes and whites was set up to work for better relations among the city’s residents. The demonstrations ended and the country felt relieved.

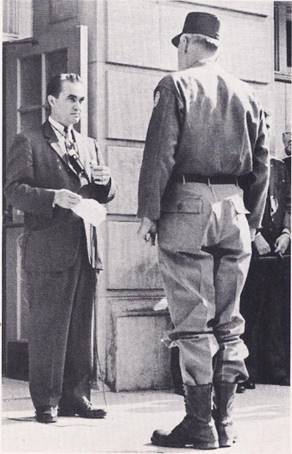

Two days later, however, the peace was shattered, after some whites who opposed the agreement bombed the homes of two Negro leaders. Thousands of angry Negroes from the working class district poured out into the streets. Up to this time, the Negroes had followed Dr. King’s doctrine of non-violence; now, for a day and a half, they rioted. The situation seemed out of control and President Kennedy sent federal troops into Alabama on May 12, keeping them just outside of the city. Calm soon returned to the city and the Negro and white communities began the difficult task of carrying out their peace agreement.

The events in Birmingham convinced President Kennedy that the federal government must do something about civil rights. Only new laws could prevent violence from spreading throughout the South. On the night of June 11, he spoke to the American people, urging their support of a new civil rights law — a law that would transfer Negro struggles from the streets, where they might cause violence, to the courts, where the issue could be worked out peacefully.

No president since Lincoln had discussed civil rights so frankly and with so much sympathy for the Negro. Explaining how inequality affected the average Negro, President Kennedy said, “The Negro baby in America today has about one-half as much chance of completing high school as a white baby born in the same place on the same day; one-third as much chance of completing college; one-third as much chance of becoming a professional man; twice as much chance of becoming unemployed . . . a life expectancy which is seven years shorter and the prospects of earning only half as much.”

Kennedy drew up a strong bill, but Negro leaders complained that it was not strong enough. Southerners, on the other hand, complained that it was entirely unnecessary. Then, on September 15, 1963, a bomb exploded in a Negro church when Sunday school classes were being held. Four Negro children were killed instantly. The bombing horrified the country and Congress put together a much stronger civil rights bill than anyone had thought possible.

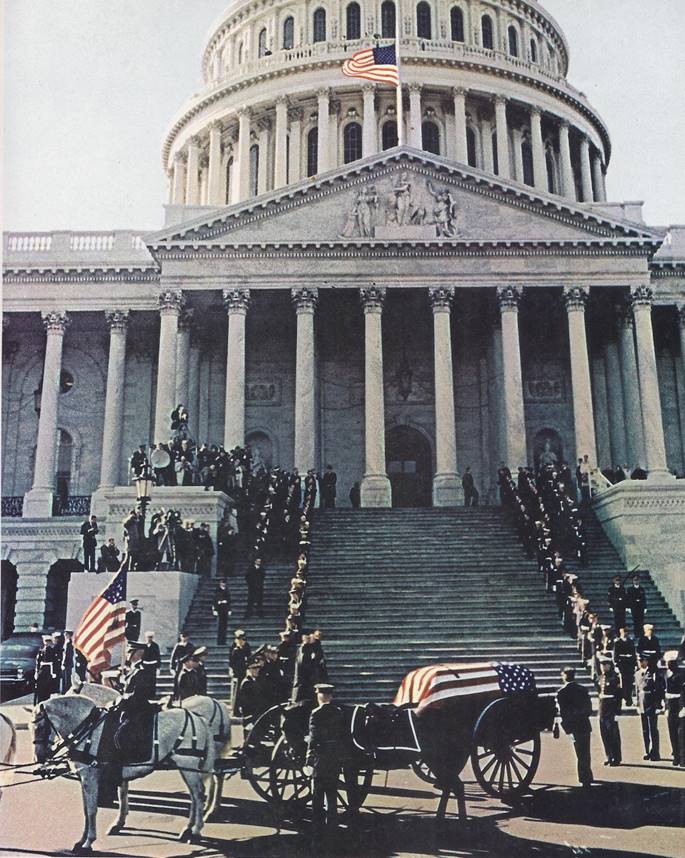

President Kennedy did not live to see the civil rights bill become law. He was assassinated on November 22, 1963, while on his way to a political rally in Dallas, Texas. He was killed by shots from a rifle, apparently fired from the window of a building overlooking the street through which he rode. The evidence indicated that the killer was a young man named Lee Harvey Oswald. A misfit from his early youth, Oswald served in the Marines, then became a Communist and went to live in Russia, where he renounced his American citizenship. Disillusioned with Russia, he returned to the United States. Just what prompted him to do the things he did would probably never become known, because he himself was killed two days later. While millions watched the scene on television, he was shot in a Dallas police station by Jack Ruby.

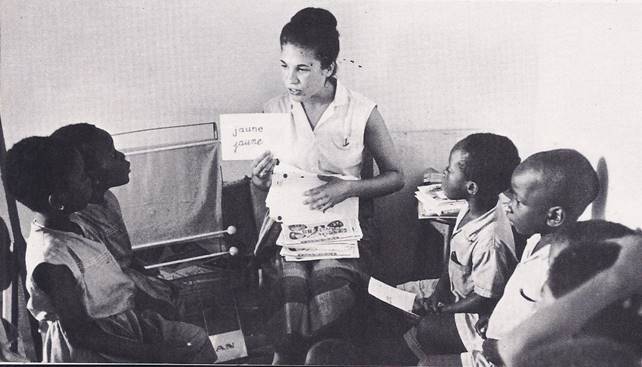

The seemingly senseless act of violence that had ended the life of the President profoundly shocked the entire world. On November 25, millions of Americans watched the funeral procession on television. As they saw the flag-draped casket borne through the streets of Washington and heard the beat of muffled drums, they knew that John F. Kennedy would be long remembered. He would be remembered for being the youngest man and the first Catholic to be elected President. He would be remembered for his courage and diplomatic skill in the Cuban missile crisis mid be remembered for establishing the Peace Corps, in which young volunteers were sent to undeveloped countries to teach and give technical aid. He would be remembered as a champion of peace and civil rights. He would be remembered for his youth, his intelligence, and his vigour and he would be mourned for having been cut down before he could see his hopes and his life’s work fulfilled.

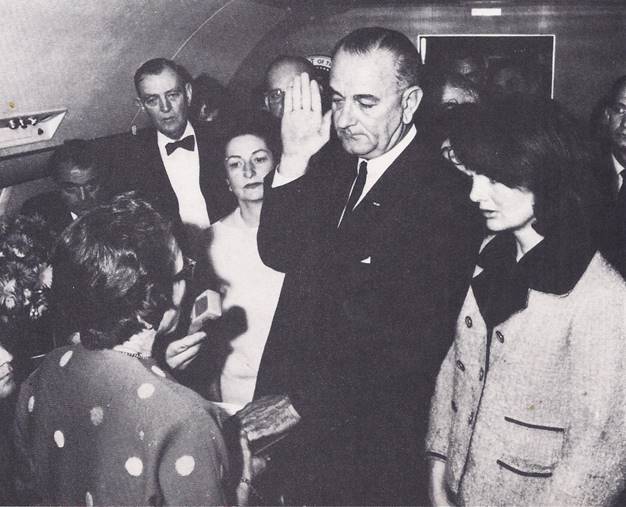

A half hour after Kennedy’s death, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as President and the world waited anxiously to see how the United States would respond to the change in leadership. A Texan, Johnson was the first Southerner to be President since the Civil War. Almost his entire career, like that of Kennedy’s, had been in politics. Before becoming Vice President, he had served in Congress for twenty-three years, first as Representative and then as Senator. During his last six years in the Senate he had been the majority leader and had acquired the reputation of being one of the shrewdest politicians in the country.

Johnson immediately promised to carry out Kennedy’s foreign and domestic policies‚ He tried to expand the area of agreement with the Soviet Union, to strengthen the foundation of peaceful co-existence. He soon showed his extraordinary political skill by persuading Congress to enact most of Kennedy’s legislative program and in 1964 Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. It swept aside discrimination against Negroes in places of “public accommodation,” such as restaurants, hotels, stores and theaters, in publicly-run facilities, such as libraries, hospitals, schools and parks, in labour unions and in federally-aided programs.

The act had a serious flaw — it failed to guarantee the right of Negroes to vote and without this right they remained second class citizens in the deep South. Early in 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King led the Negroes of the small city of Selma, Alabama, in a protest against the city’s refusal to register them as voters. On March 8, they tried to march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, fifty miles away, to present a petition to the governor. They were met by police, state troopers and posse men who used tear gas, whips and clubs to beat them down. The following day, a white minister from Boston, who had come to Selma to support the protest, was attacked; he later died of a fractured skull.

Again the nation war horrified and protests in sympathy with the Negroes took place in communities throughout the North. Congressmen of both parties promised to act swiftly to insure that Southern Negroes would have the right to vote.

On March 15, President Johnson went before Congress and the American people to discuss a new voting rights law and the question of civil rights in general. His speech was one of the most remarkable in the history of the presidency, for never before had a President identified himself so completely with the cause of the Negroes. He compared the civil rights struggle at Selma to the great struggles for freedom at Concord and Lexington and Appomatox. “The time for justice has come,” he said. “No force can hold it back. It is right — in the eyes of man and God — that it should come and when it does, that day will brighten the lives of every American.” Slowly and forcefully, he repeated the refrain of the song that had become the anthem of the civil rights movement: “We shall overcome.”

Two days after his speech, President Johnson sent to Congress a bill that would give Negroes the right to vote in every state and community where it had been denied them. No one believed that the struggle for civil rights was over. There was still much work to be done; there would still be opposition; there might still be outbreaks of violence. No one could doubt that the hope for full political equality of all American citizens, the hope that had been raised by the Supreme Court decision of 1954, would someday be fulfilled.