“I DID NOT come to till the soil like a peasant,” said Hernando Cortez. “I came to find gold.”

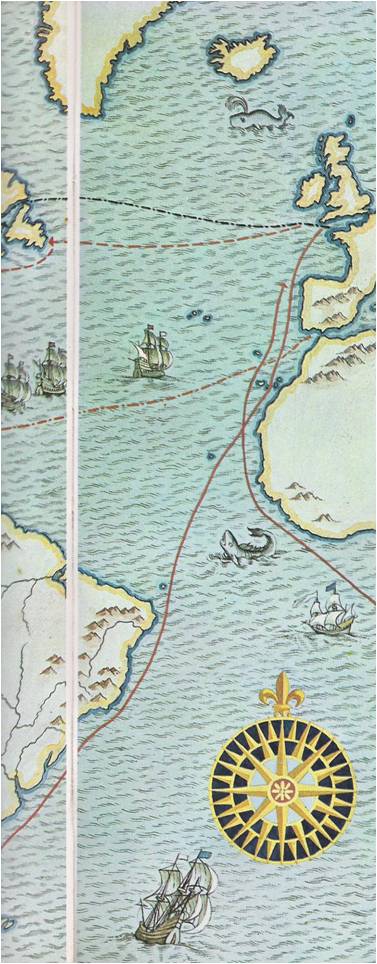

His words echoed the thoughts of almost every Spaniard in the New World. The discovery of the sea route to the West had set off a great treasure hunt. Colonizing and slaughtering, building and plundering, the gold-hungry Spaniards won a Spanish Empire of the West. Conquistadores‚ they were called — the conquerors.

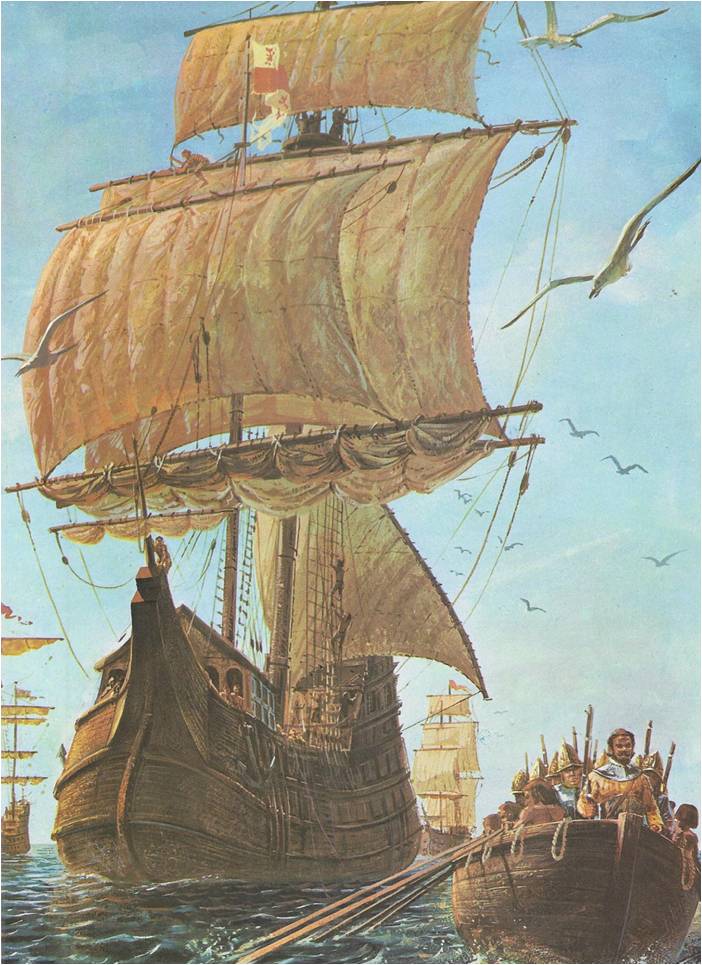

None of the treasure-hunters was more cunning or ambitious than Hernando Cortez‚ who came to the island of Hispaniola in 1504. It was not until 1519 that the governor of Hispaniola sent him on an expedition to explore the coast of Central America. Cortez sailed with five ships, 500 soldiers, eleven cannon and fifteen horses. The fleet anchored near the coast of the territory called Mexico and the men went ashore to build a settlement. Cortez ordered the ships dismantled so that none of his men could go back to Hispaniola, then set off on a march inland.

Mexico was a vast country whose Indians had built a highly organized civilization and Cortez had a force of less than 500 men. He was a skillful leader; besides, he had firearms and horses –and good luck. Not long after he began his march, a horde of Indians swept out of the hills to attack the Spaniards. As soon as the Spanish cavalry appeared, the Indians fled to safety. As one soldier later wrote, the Indians, “who had never before seen a horse, thought that steed and rider were one creature.” One tribe after another surrendered. They had been conquered by the people called the Aztecs and many of them offered to join Cortez in the fight to destroy the Aztec empire.

As the Spaniards and their Indian allies pushed on into Mexico, couriers came from the Aztec emperor, Montezuma. They all brought the same message: “Come no further into Mexico. It will not be good for you or for us.” With the messages came gifts — cartwheels of gold, silver plaques, richly designed capes of feathers. Montezuma meant them as offerings of peace, but to the Spaniards they were proof that the land was full of treasure.

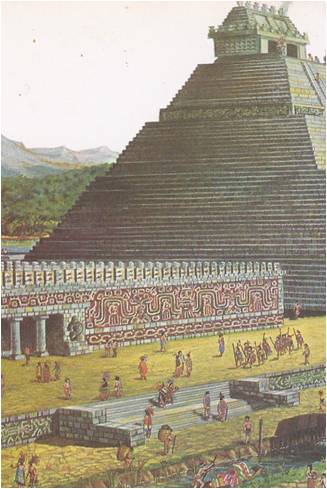

Over the mountains, toward the great central plateau of Mexico, Cortez led his troops and everywhere were new signs of the wealth of the Aztecs. Dazzling cities with temples and houses of splendid stonework rose above the brown hills. Often the cities were opened to him without a fight. The Aztecs believed that once they had been ruled by a god with a light skin and a beard, a child of the sun. He had left the land, sailing east on the sea, but he had promised to return. Cortez had a light skin and a beard his armour shone like the sun and he had arrived by ship from the east. He rode a strange beast and had weapons that thundered. Surely‚ here was the god returning at last!

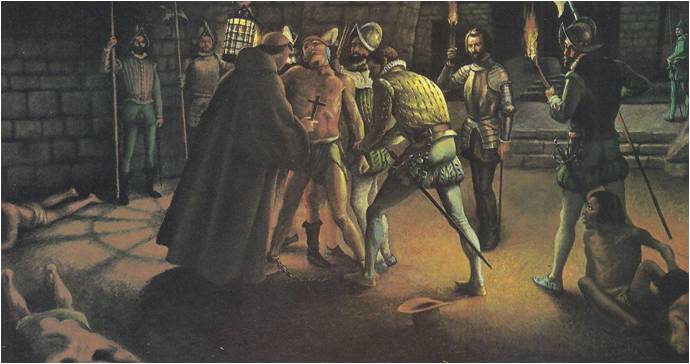

The Emperor Montezuma must have soon realized that Cortez was a man and not a god. He could not say so openly; his people might become angry and rise up against him. When Cortez reached the capital city, Montezuma greeted him as an honoured guest. The splendour of the city and its palaces amazed the Spaniards. Secretly visiting some rooms they had not been invited to see, they found them heaped high with treasure. For four days Cortez enjoyed the emperor’s hospitality. On the fifth day he quietly made Montezuma his prisoner.

THE CONQUISTADORS

Cortez assured the shocked Montezuma that he would not be harmed, that he would still command his people and see his noblemen. Montezuma did indeed continue to issue orders to the Aztecs — but the orders came from Cortez who had conquered a city by gaining power over its ruler. In the name of the emperor, the Aztecs’ gold and silver were collected for Spain and the people of Mexico began to pay taxes to the Spanish king. It was the greatest treasure that had ever fallen into the hands of the Spanish. Cortez kept his word. The emperor was not harmed‚ his noblemen came and went as they pleased and there was peace.

When Cortez went south to oversee the building of ports on the coast, the officers he had left behind quarreled with the Aztec nobles and had several of them killed. The people rose in revolt against the Spaniards. Montezuma tried to calm the people; they killed him and drove the Spaniards from the city.

Cortez took the city again, this time with soldiers and cannons. In the fighting‚ many of the palaces, mansions and handsome homes were destroyed. After that, the Spaniards ruled with an iron hand. Raiding parties destroyed Aztec strongholds in every part of Mexico. By 1522. the Aztec Empire was no more; its people, its lands, its treasure, belonged to Spain.

The Spanish king appointed Cortez as governor of the conquered country which was now called New Spain. Priests joined the soldiers in the new settlements and old Aztec cities. They worked tirelessly to win the Indians away from their old gods, whose laws had been harsh and whose holy days had been celebrated with human sacrifices. In Europe, thousands of persons were turning away from the Church of Rome to the churches of Luther and Calvin, but in New Spain the Roman Catholic Church made countless converts to add to its strength.

Other fortune-seekers plotted against Cortez and he never won the power and fame he thought he deserved. When he died in 1540, his deeds had been outdone by the most ruthless of the conquistadors, Francisco Pizarro. Pizarro had marched with Balboa through the jungles that edged the Pacific Ocean; from the Indians he had heard tales of the country of the Incas, a country filled with treasure. He persuaded Charles V, the emperor of Spain, to outfit an expedition to South America and in 1532 he set sail from Panama to the country that would one day be called Peru.

Pizarro’s force was small — about a hundred foot soldiers and sixty cavalrymen — but he was sly and clever. He told the natives that he had come with friendly greetings from a far-off king to the Incan emperor, and they pointed out the way to the cities of the Incas. The way was long and hard, over the mountains called the Andes. Word of him went ahead and when he reached Incan territory he saw that the Incan emperor had assembled a vast army in a valley.

Pizarro made camp on the heights and invited the emperor to a friendly conference. The emperor accepted. He came with hundreds of his noblemen and servants and he came unarmed. Pizarro gave a signal to his men, who seized the emperor and attacked his followers. Within half an hour hundreds of the unarmed Indians lay dead; the rest fled, leaving the emperor a prisoner. He offered to pay for his freedom with enough gold to fill a room and Pizarro agreed. The Spaniards watched greedily as the Indians carried in magnificent plates and goblets and intricate ornaments of gold. When the room had been filled, it held more than $9,000‚000 worth of treasure. No monarch had ever paid such a huge ransom, but it failed to save the emperor of the Incas. He was killed at Pizarro’s order.

Pizarro then marched his soldiers higher into the mountains, to Cuzco, the capital city of the Incan Empire. There rose mansions and temples decorated with rich hangings, mosaics and dazzling ornaments of precious metals. The empire of the Incas was richer than the Aztec Empire Cortez had found in Mexico and its civilization was even more advanced. Pizarro announced that the empire now belonged to Spain, and officials who refused to cooperate were seized and burned.

The Indians did little at first to defend their cities. Pizarro’s men marched north and south, while he organized the land and arranged for shipments of gold to Spain. He ordered the building of a new port for the inland town of Lima, that would soon become the key city of the Spanish empire in the New World. The greed and cruelty of the Spaniards drove the Indians to revolt. While Pizarro struggled to put down the rebels, the Spaniards began to fight among themselves for their share of the riches. Pizarro was murdered by one of the plotters. During his nine years in the land of the Incas, he had found the greatest treasure discovered in the New World and now it was left for his enemies to divide among themselves.

Despite the rivalry among the conquistadors, the Spanish conquest of South America continued. Almost all of the western side of the continent came under their rule. One group of adventurers turned east across the Andes, making their way through steaming jungle to the headwaters of a great river — the Amazon. They followed the river across the continent to Brazil and the coast of the Atlantic Ocean, a feat that would not be repeated for 500 years.

DE SOTO AND CORONADO

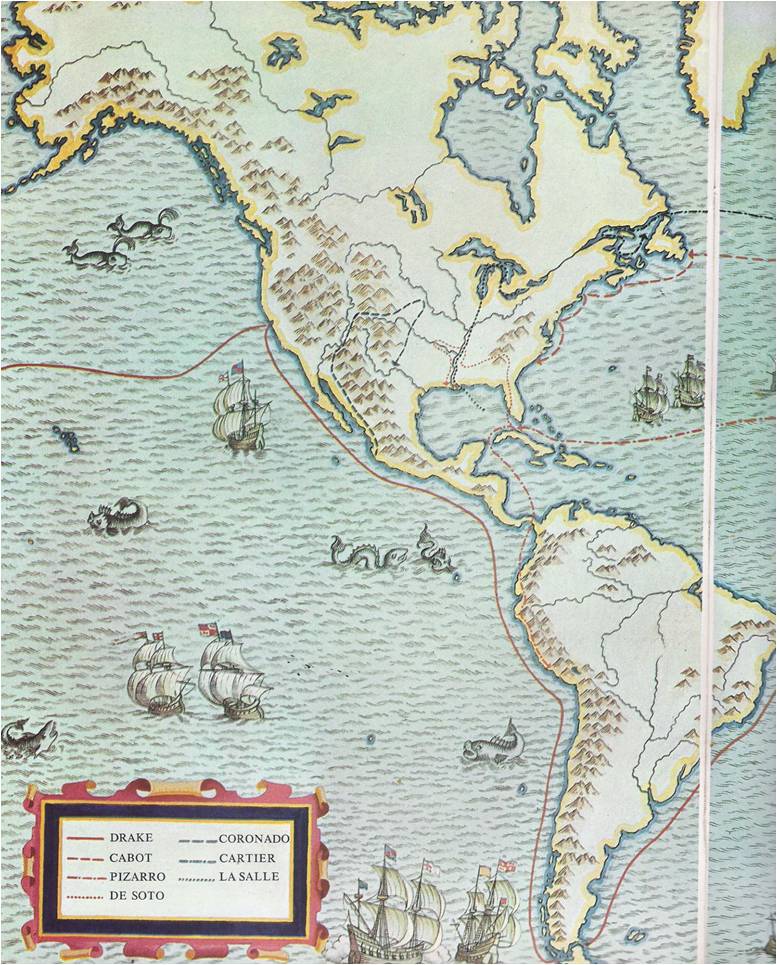

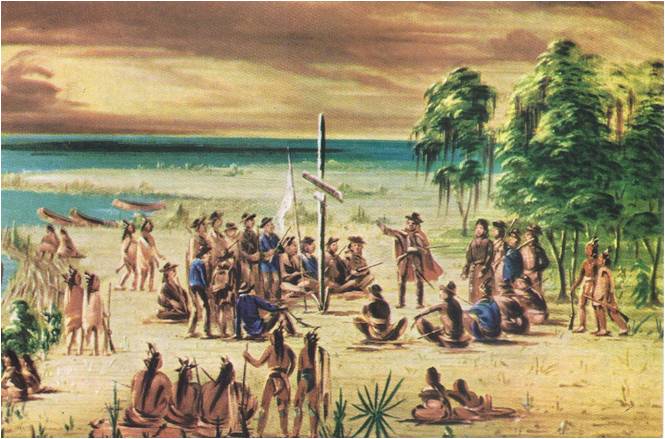

The riches discovered in Mexico and Peru encouraged the fortune-hunters to explore North America. In 1539, Hernando de Soto, who had been with Pizzaro‚ led a large expedition to Florida. He found no treasure there, and the fierce Seminole Indians attacked him again and again. De Soto fought them off as best he could and pushed on into the territory that would later be called Georgia and the Carolinas. Tuning west, he marched across Alabama and Mississippi to a mighty river which years later would be named the Mississippi. In the swamplands, he died of a fever. His soldiers feared the Indians would attack if they learned that the invaders’ commander was dead. The Spaniards wrapped up De Soto’s body, weighted it and sank it in the deepest waters of the river. Then they followed the river to the coast and sailed west to Mexico, where they reported their experiences to the governor.

The Spaniards did not give up their quest for gold in North America. From the Indians they heard of El Dorado, the city of gold that lay somewhere beyond and eager explorers searched for it. In 1540, Francisco Coronado led an expedition north from Mexico and came upon the Colorado River. A group of his soldiers explored the river’s course and came upon a wonder of nature, the Grand Canyon. Coronado himself marched east, following the river known as the Rio Grande. He journeyed across the country that would later be called the panhandle of Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. He found no gold and disappointed, he turned westward again and returned to Mexico.

No one ever did find El Dorado, but years passed before the Spaniards gave up hope of finding it. As they searched, they conquered more territory. California and Baja California were added to the empire that already included the West Indies, Central America, the western side of South America, Mexico and the western and southwestern parts of North America. Colonists, priests, and soldiers poured into the new territories. They built towns and churches and forts that would for centuries mark the land as Spanish, even after the Spanish governors were gone. Gold from the real treasure cities, the cities discovered by Cortez and Pizarro, flowed across the sea to Spain in a steady procession of heavily laden galleons. The gold bought power for Spain. For almost a century she would rule the seas and be the greatest power in Europe.

By command of the pope, the New World and Europe’s trade routes to the east and west were officially divided between Portugal and Spain. The monarchs of Europe, still loyal to the pope, obeyed; besides, they had no idea of the size or wealth of the Americas. Then came Martin Luther and the Reformation. At the same time, the first shiploads of gold arrived from Mexico and Peru, while ships were returning from India laden with spices. More than one monarch‚ turning to the new religion, was ready to forget the papal treaty and their sea captains began to stray south and west.

Queen Elizabeth, who came to England’s throne in 1558, saw no reason to abide by a treaty upheld by a pope who had declared she was no queen at all and Spain was her mortal enemy. Moreover, she felt she had an honest claim to a large share of territory in the New World. Long before the Spaniards had explored the coast of North America, it had been sighted by an Englishman — or at least by a captain sailing under the English flag.

THE NORTHEAST PASSAGE

That captain was Giovanni Caboto, an Italian from Genoa. In 1497, when Europe buzzed with tales of Columbus’ first voyage, he persuaded Elizabeth’s grandfather, Henry VII, to outfit an expedition. With an English ship and an English name — John Cabot — the captain set out for what he thought was Asia. He followed a course far to the north of the one Columbus had sailed and returned with reports of icy waters swarming with fish and of rocky, fog-bound islands, Cape Breton and Newfoundland. On a second voyage, in 1498, Cabot sailed down a ragged coast that stretched on for hundreds of miles. It was the edge of North America and Cabot was the first European to visit it since the days of the Vikings. Cabot made a third voyage, but his ships met disaster somewhere on the North Atlantic and he was never heard from again.

Cabot’s son, Sebastian, was also an explorer. After making one voyage for England and another for Spain, he returned to England. He talked of a Northeast Passage, a route to Asia over the top of Europe and London’s businessmen listened. They had banded together in companies of merchant adventurers to which the king had granted the right to find new markets and manage foreign trade. They had already opened trading centers in many ports in northern Europe, but they longed to find a way to the greater riches of the East. In 1553, they sent Cabot on an expedition that sailed northeast, above Scandinavia. He found no passage to the Indies, but he did cross the White Sea north of Russia. Travelling by land, he came to Moscow and the court of Ivan the Terrible. Despite his name, Ivan gave Cabot a hearty welcome and soon Englishmen were trading with the Russians.

Now that the merchant-adventurers knew no Northeast Passage existed, they began to think again about the sea routes leading south and west. There was little they could do when Henry’s daughter, Mary, became queen; she had a Spanish husband and allowed nothing that might offend Spain but under Queen Elizabeth, the sea captains began to venture into forbidden territory.

About 1560, a crafty captain named John Hawkins discovered a profitable trade in southern waters. He slipped down the African coast, picked up slaves and carried them to the West Indies, where the settlers paid high prices for laborers to work their plantations. Hawkins added to his profits by plundering lone treasure ships he met along the way. His business came to a sudden end when a Spanish squadron trapped his little fleet in a West Indian harbour. Barely escaping with his life, Hawkins went home to England.

SIR FRANCIS DRAKE

Hawkins’ nephew, Francis Drake, refused to be frightened away from the Spanish sea routes. With the aid of London merchants, he obtained ships and crews, sailed away to become the most successful ocean going highwayman the world had known. He waylaid galleons in the West Indies, raided the ports of Central America and brought his vessels home loaded down with gold and silver. Drake gave an honest share of his booty to his merchant sponsors and the queen’s treasury and Englishmen agreed he was no pirate.

Then Drake turned to a bolder project. He sailed his stoutest ship, the Golden Hind, down the eastern coast of South America. Following the Strait of Magellan into the Pacific Ocean, he went north, past South America and Mexico. He stopped to repair his ship in California and continued north to the coast of Washington. From there be went west, crossed the Pacific and sailed through the Indian Ocean and around the coast of Africa to Europe. He had matched Magellan’s feat of navigation and Queen Elizabeth rewarded him by making him a knight of the English court. The man the Spaniards called a pirate was now Sir Francis Drake.

THE SPANISH ARMADA

Many young men, French as well as English, followed Drake’s example and set out to plunder Spanish ships and ports. Their headquarters was a wild stretch of coast on the West Indian island of Haiti. They ranged the ocean highways along the northwest coast of South America, the route called the Spanish Main.

Buccaneers, they were called — and in 1588, many of the English buccaneers took part in a great sea battle close to their homeland. King Philip of Spain, who had long been the enemy of Queen Elizabeth, had made up his mind to destroy her sea power and conquer her kingdom. After two years of preparation, his war fleet, the Armada, set sail for England. It was the greatest force raised by a monarch in the history of Christendom — 130 ships carrying 8,000 seamen and about 20,000 soldiers. The English learned of the coming attack and knew that they would be outnumbered. They called home every available ship and put them under the command of the earl of Nottingham and Sir Francis Drake.

When the Armada sailed into the English Channel, it was a terrifying sight. As the English ships came out cautiously to meet it, a violent storm came up. The Spanish vessels were undermanned, overloaded and top-heavy; many of them sank. The others were easy prey for the swift English raiders. The storm shifted, blowing the Spaniards northward, past England and the tip of Scotland, then west and south again into the rough channels between England and Ireland. Drake and his captains followed, picking off one ship after another, until the battered remnants of the Armada crept home to Spain.

This disaster ended Spain’s years of greatness on the seas and the English were quick to take advantage of it. They formed new companies of merchant-adventurers and Elizabeth granted them the right to send explorers, colonists and traders to the new lands.

In 1585, Elizabeth had allowed her favourite, Sir Walter Raleigh, to send the first group of English colonists to America. They founded the Roanoke Colony, on an island off what would be called North Carolina. All but fifteen of the first settlers returned to England. They said the new land was too wild, too strange and the Indians too fierce. A second group of settlers was massacred by the Indians and Raleigh then sent a third group. What became of them was never discovered. When a ship put in at the island, there was no sign of the settlers and Roanoke became known as the “Lost Colony.”

The English merchants were not discouraged. They came to the queen with plans for a new company and a new colony to be called Virginia. Elizabeth died before the plans were completed, but in 1606 her successor, King James I, granted a charter to the Virginia Company of London. The following year, the company’s first group of colonists began the settlement of Jamestown. They were more interested in searching for gold than in doing the necessary work and within a few months it looked as though hunger, sickness, lack of shelter and Indian raids would end the venture. Then gruff, shrewd Captain John Smith took command. “You must obey this now for a law,” he said, “that they that will not work will not eat.” He also made peace with the Indians and began trading with them for food. Jamestown survived and gradually began to thrive.

VOYAGE OF THE MAYFLOWER

When the news reached England, another company was formed to establish colonies farther north on the American coast. The Plymouth Company had difficulty finding settlers to live on its land until a group of Puritans came there by accident. The Puritans were people who wanted to worship God in their own way; this was not easy to do in England after James I forbade any churches except the Anglican church. In 1620, some of them hired a little ship, the Mayflower‚ to take them to Virginia. Blown off course, they came instead to the land that would be called Massachusetts and there they stayed. In spite of many hardships, especially during the first winter, the colony grew.

Like the English, the Dutch and the French had come to America before, searching for a route to India, the Northwest Passage, that did not exist. Now they returned to plant trading posts and settlements and to share the riches of furs and vast tracts of fine timber.

The Dutch had always been seafarers and had founded their own companies of merchant adventurers. It was an Englishman, however, who led them to North America. In 1609, the Dutch East Indies Company hired Henry Hudson to search for the Northwest Passage. He found no passage, of course, but he did find a great river and farther north, a huge bay, both of which would later be given his name. His career as a navigator was cut short when his crew mutinied, set him adrift on the bay in a tiny beat and rushed away from the terrors of the north. Hudson’s employers profited from his discoveries. They went into the fur trade, sending ships to collect pelts from trappers up the Hudson River and along the coasts of Connecticut and Long Island.

Other Hollanders bought a rocky island from the Manhattan Indians in 1624 and established the colony of New Amsterdam. It soon became prosperous — too prosperous, in fact, for it tempted the English, whose colonies now dotted the coast on either side of the Dutch territory. In 1655 an English fleet attacked the town without warning, captured it and set off a war that lasted nearly twenty years. In time the Dutch gave up their claims to any land in the north and New Amsterdam became New York.

The French settlers in little settlements and forts north of English colonies were determined not to be driven out. They reminded the English that France had also sent an explorer to search for the Northwest Passage. Jacques Cartier had sailed around Newfoundland and into the wide waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 1534. On a second voyage, he had explored the river that flowed into the gulf and that, the French settlers said, gave France a claim to all the land north of the St. Lawrence.

It was true that for almost seventy-five years the French did little about it; they had no merchant companies to set up colonies. Individual Frenchmen-traders who wanted furs, missionaries who wanted to convert the Indians and men who simply wanted adventure — at last set out to explore the Canadian wilderness. In 1608 Samuel Champlain built a trading post he called Quebec. He also mapped the rivers that ran into the St. Lawrence and discovered Lake Champlain and two of the Great Lakes, Huron and Ontario. Jean Nicolet, a young man he had trained, pushed farther west and south, to Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. The Indians told him of the “Great Water” not too far off, but he never found it. However, in 1673, Louis Joliet and Pére Jacques Marquette, a priest‚ led a party of five woodsmen into the wilderness and came upon the Great Water. It was a long, broad river that the Indians called Mich Sipi a name that white men turned into Mississippi.

NEW ENGLAND AND NEW SPAIN

A French nobleman named La Salle believed that a chain of forts and colonies along the river would give France control of much of North America. The king was not interested in his scheme and when La Salle tried to carry it out himself, he met with disaster. He led an expedition down the river from the north and back, and planned a second journey to start at the river’s southern end of the Gulf of Mexico. Three times he tried to find the spot where the river flowed into the gulf and three times he failed. His weary and hungry men demanded that he take them home. When he refused, they killed him.

Other French adventurers continued to make journeys into the continent, some traveling up the Ohio River and the Tennessee. Meanwhile, in the territory that was beginning to be called New England, new colonies were settled by merchant companies and by bands of men and women who wanted to worship as they pleased. At the same time, the Spaniards were building towns and missions along the coast of California.

Much of the New World and its surrounding oceans — the lands and the waters that Europeans had not even imagined two centuries before — was now charted. On the maps of the two new continents were marked the territories claimed by Portugal, Spain, England, the Netherlands and France. Here was space where men could live and worship in many ways, in the ancient way of the Roman Catholic Church or the new ways brought about by the Reformation. The age of discovery and reformation was coming to an end, but men would go on exploring the world around them and the world of thought, bringing about still further changes they could not yet imagine.