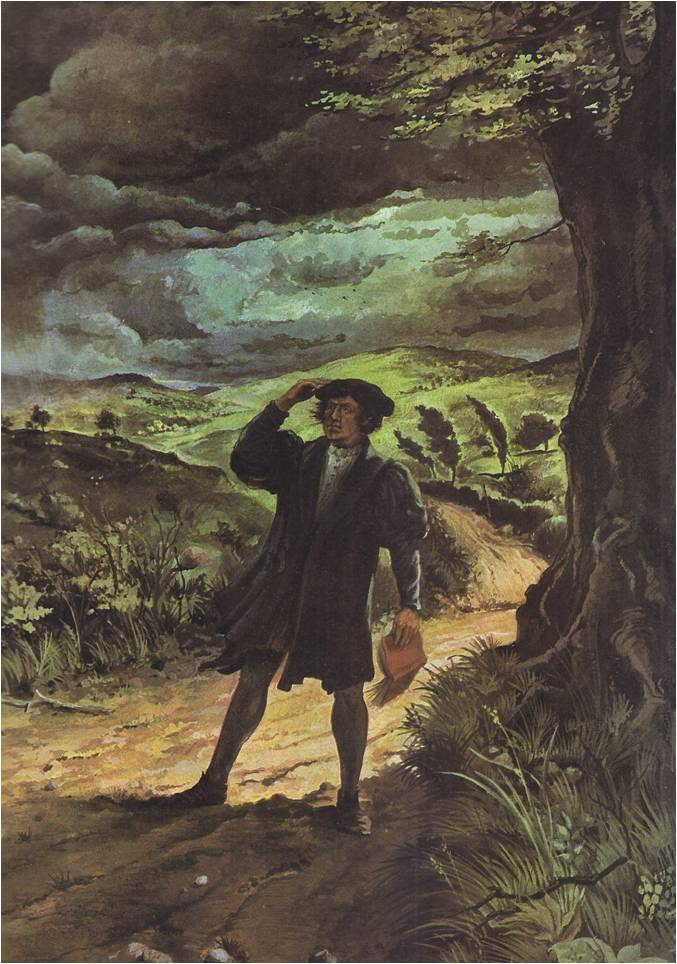

ON A SULTRY JULY DAY IN 1505, a young law student, Martin Luther, was walking along a country road in Germany when a summer storm blew up. The air grew heavy and black clouds filled the sky. Before Luther could take shelter, thunder began to crash. A bolt of lightning struck the road almost at his feet. Thrown to the ground, he lay shaking, not certain whether he was alive or dead. “Help me, Saint Anne,” he cried, “help me and I will become a monk.”

After a moment, Luther’s trembling stopped. He stood up, found that he was not hurt and continued his walk toward Erfurt, the town in which he attended the university. He did not forget his promise to Saint Anne. He spent a week or so thinking and making plans. Then he told his professors that he could come no more to their classes. He sold his books, bade farewell to his friends and went to the monastery of the Augustinian friars and said that it was his wish to become a monk.

When Martin’s father, old Hans Luther, heard what his son had done, he was puzzled and angry. Hans had worked hard all of his life. Though his ancestors had been peasant farmers, he had managed to set himself up in a little business. But he was far from rich; he had scrimped and saved to send his son to school and to the university. He had long looked forward to the time when Martin would be a lawyer, a man of standing who would make his parents proud and earn the money to care for them in their old age. Now those plans were ruined. As a monk, Martin would never win fame or riches. Hans was furious and he wrote to Martin demanding that he change his mind.

THE LEARNED SCHOLAR

Martin ignored his father’s demands. He would not break his promise to Saint Anne. Besides, he had long been struggling to make his peace with God and in becoming a monk he hoped that he could do that at last. For as long as he could remember, he had feared the anger of God. He had grown up in a village where fathers and schoolmasters beat obedience and learning into children. At church he had been taught about a God, the father and teacher of all mankind, who spoke in thunder and tortured the souls of dead sinners with dreadful, unending punishments. Everyone, he was told, was full of sin — that was the nature of man — and he would have to struggle to avoid evil and the punishment it brought.

Little Martin did struggle to be good. He tried to obey his parents, he did his best to live up to God’s commandments, but he could never feel certain that he was not a sinner. When he grew older and went to the university, the old fears still haunted him. He studied hard and did his work well. He went regularly to mass, confessed his sins and faithfully did penances, the prayers and acts of charity by which a man could win forgiveness for his evil deeds.

Then came the day of the storm. Martin Luther faced death and he knew that if he died at that moment, he would surely be condemned as a sinner. The gates of heaven would never be opened to him. At best, he would be sent to spend centuries in purgatory, the half-way place between heaven and hell, where the souls of the dead lived in torment until they had paid for their earthly sins. So Luther made his desperate plea to Saint Anne and afterward went gladly to the monastery.

In the first weeks of his new life, Luther felt that he had indeed found a way to live that would satisfy God. Monks and nuns observed the strictest kind of discipline. They swore never to marry, to live in poverty and to serve God in all they did. They labored at any task assigned to them and they fasted and prayed to purify their heart of all worldly things. Novices‚ new members of a monastery‚ spent a year on trial before they officially became monks. Their tasks were hard and humbling. Luther laboured in the kitchens and barns, scrubbed flours and did other lowly work. He was awakened at one or two o’clock each morning for the first of the day’s seven times for prayer.

When the year of trial was done, Luther was welcomed into the brotherhood of monks. For the first time he was allowed to say mass, to serve at the alter and to touch the holy bread and wine. At one moment during mass he was so frightened at the sudden feeling of the nearness of God that he almost fainted. He somehow managed to go on and afterward he went proudly to greet his father, who had come to watch the service. Old Hans had done his best to be more understanding.

He had even brought a generous gift of money to the monastery. When he spoke to his son, the boy who should have been a prosperous lawyer, his anger rose up again. “You learned scholar,” he roared at Martin, have you never read in the Bible that you should honour your father and mother? Here you have left me and your dear mother to look after ourselves in our old age.”

His son’s answer was quiet but firm: “I can do more for you with my prayers.”

In the months that followed, however, Martin Luther began to wonder if he could help even himself with his prayers and his life as a monk. No brother in the monastery was so zealous as he in fasting and doing penances. He went as long as three days without food, tortured his body by sleeping on the stone floor of his cell and spent hour after hour on his knees praying. Yet he always he felt weighed down by the terrible burden of his sins.

RELICS AND INDULGENCES

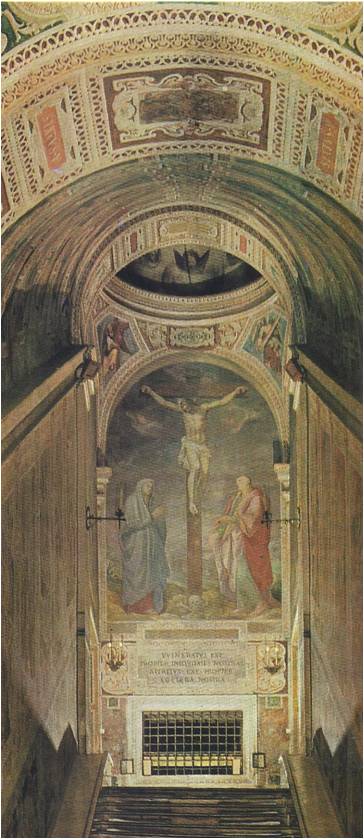

In 1510, when he was twenty-seven, he was sent on business to Rome. He was filled with new hope as he journeyed to the great city. Here, in the capital of the Church, he was certain that he could make his peace with God. In Rome there were dozens of shrines, chapels and thousands of relics of the saints. One burial vault alone held the bodies of 76,000 martyrs and 40 popes. On display in Rome was a piece of Moses’ burning bush, the chains that had bound St. Paul and a coin that had been paid to Judas for his act of betrayal. In front of the palace called the Lateran were the Scala Sancta, the twenty-eight “Sacred Stairs” that were said to have stood before the palace of Pilate. If a man crawled up those stairs and stopped to pray at each step, he could win release from purgatory for one soul, the soul of any dead relative or friend he chose to name — or so it was said.

There was something to be gained by visiting any of Rome’s sacred relics. Each time a man looked at one of them he was excused from a certain number of years of purgatory. The exact number varied according to the importance and holiness of the relic and the churchmen kept a careful list of the exact value of each. These pardons from purgatory, called “indulgences,” were officially granted by command of the pope. He was thought to have the power to “borrow” quantities of goodness from a heavenly treasury. This treasury was filled with the infinite merits gained by Christ through his suffering and death. It also contained the merits left over from the saints and others who had done so much good that they got into heaven with goodness to spare.

An indulgence was like a check signed by the pope. It was worth a certain amount of goodness from the saintly treasury and it could be deposited in the heavenly account of any man whose own supply of goodness was dangerously low. If a visitor in Rome went to see enough relics, he went home with a handful of these indulgences, a comforting supply of pardons for the sins he feared he had committed.

While Martin Luther was in Rome he went to look at many of the most sacred church relics and he collected his reward of indulgences. He visited the most sacred shrines in Christendom and attended mass in the pope’s own church. Somehow his stay in the holy city was a disappointment. The Roman priests shocked him. They rushed through the mass and mumbled their prayers. The Roman monks seemed to have forgotten about their vows of poverty and fasting; they lived well and their tables were laden with rich food and fine wines. Viewing the relics did not make Luther feel less sinful. Indeed, when he had crawled up the twenty-eight steps of the Sacred Stairs and tried to pray for a soul in purgatory, the words would not come. Instead, he whispered to himself, “Who really knows if it is so?”

More worried than ever, Luther went home to Erfurt. Then he was sent to study and teach at the university at Wittenberg. He laboured over his books, grew thin from fasting and long hours of work and wondered how he could ever teach anyone about religion when he did not know the answers himself. At Wittenberg he did find someone to whom he could talk to about his problems and fears — Dr. Von Staupitz, one of the leaders of the Augustinian order. The old scholar was as kindly as he was learned and he took a particular interest in the serious-minded young monk. In the afternoons, as they sat and chatted in the shade of the pear tree in the monastery, Staupitz did his best to put Luther’s mind at case.

When Luther spoke of the wrath of God, Staupitz reminded him that God was forgiving as well as stern. When Luther brooded, Staupitz suggested that he spend his time studying instead. When Luther said that he could not understand the word of God in the Bible, though he read it over and over, Staupitz appointed him to teach university classes in the meaning of the Bible. Martin protested, but the old scholar was firm. “Read the words,” he said, “until they make themselves clear to you.”

As Luther poured over his Bible, trying to think what he could say to his students, the words did come clear. He was puzzling over the curious phrase, “The just live by faith,” when he suddenly saw the answer to the problem of sinfulness that had troubled him so long. “The just live by faith. . .” Did these words not mean that all God wanted of men was their faith in Him and in Christ, his son, who had suffered and died for the sake of the sins of all mankind? It did not matter, then, that men were as sinful as Luther’s schoolteachers had said they were. If a man put his faith in God’s mercy, he would be saved and would find a place in heaven when he died.

“I felt suddenly born anew,” Luther wrote years later. “It seemed that the doors of Paradise were flung wide open to me.”

Now he understood why all the fasting and penances had brought him no peace of mind. Such things did not count with God. Neither did indulgences, pilgrimages, visiting relics or crawling up twenty-eight sacred stairs. Only faith mattered.

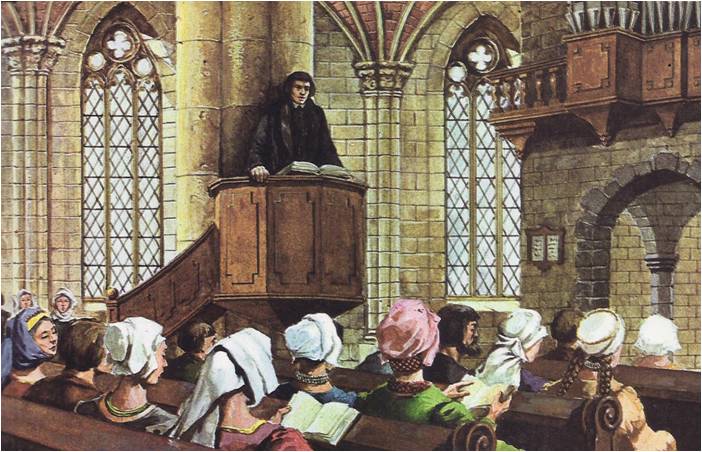

LUTHER PREACHES

Luther wasted no time in sharing his discovery. He preached about it in the church at Wittenberg and lectured on it at the university. Townspeople, students and monks alike were excited by his ideas. In his new kind of faith they found not only hope but a new feeling of being close to God. In the past, their religion had often been merely a matter of ceremonies, duties and donations. Now it was a private communion between each man and his Father in heaven.

Luther was pleased by the success of his lectures and sermons, for he felt that he was leading his listeners back to the simple, sincere ideas of the early Christians. It did not occur to him that he might be starting a rebellion. Before long, however, his beliefs stirred up a controversy.

On November 1, 1516 — A11 Saints’ Day — the castle of Wittenberg was opened to the public and its great collection of religious relics was put on display. This was an annual event greatly enjoyed by Frederick the Wise, the prince who ruled the town and the countryside beyond. Frederick had spent years and thousands of gold florins collecting the relics. He had a thorn that was supposed to have come from the crown of Christ, one of St. Jerome’s teeth, four hairs from the head of the Virgin Mary and three pieces of her cloak, a wisp of straw from the Christ child’s crib, one piece of gold from the gifts of the Wise Men and three of myrrh, a piece of bread from the Last Supper, one twig from the burning bush of Moses, six bones of St. Bernard and four of St. Augustine. Altogether, there were nearly 20,000 relics in the collection.

For the people who viewed them, the pope had graciously granted indulgences that amounted to 1,902,202 years and 270 days of pardon from purgatory. Of course, anyone who wanted to see the relics had to pay an admission charge to the prince. No one complained. After all, one had to pay to look at relics anywhere and Frederick did use the money to pay the expenses of the castle church and the university.

FREDERICK AND TETZEL

The prince was surprised and not at all pleased when, on the night before All Saints’ Day, one of the teachers in his university, Brother Martin Luther, preached a sermon in which he said that relics and indulgences were not of much use. No one, he said, could know if sins were completely forgiven. It was much safer to depend on confession, repentance and faith.

Frederick told Luther that he thought the sermon was a mistake and the next year, when All Saints’ Day drew near, all Wittenberg waited to see what the monk would do and say. By then, however, Luther had found a much greater annoyance to preach about and he was ready to challenge a much more powerful prince. The pope had issued a new “Declaration of Indulgence” in order to raise money for the mammoth new cathedral, St. Peter’s, which he was building in Rome. His representatives roamed every corner of Christendom, selling pardons from purgatory.

In Germany, a Dominican monk named Tetzel was hawking indulgences like a peddler selling souvenirs at a fair. Tetzel marched into town squares heralded by trumpeters and drummers and followed by a band of monks carrying Church banners and crosses. When a crowd had gathered, Tetzel preached. He spoke of the torments of hell and purgatory and told terrible tales of men who died with their sins unforgiven. When his listeners were well frightened, he displayed the pope’s declaration. Here, Tetzel said, was a way to escape pain and punishment. Although the Church taught that an indulgence benefited only the truly repentant, Tetzel said that simply by purchasing one, a man could cancel out his sins — or indeed those of anyone he wished, living or dead.

People flocked to buy, though Tetzel’s prices were high: 25 gold florins for kings, queens and bishops; 20 for abbots, counts and barons; six for lesser nobles; three for burglars and merchants; one for lesser men. With the poor, Tetzel was generous. They could win indulgences by praying and fasting. Most of the people paid cash — it was simpler and easier. Money poured into Tetzel’s collection box and out of Germany to Rome.

Tetzel was not allowed to do business in Wittenberg. However, he came as close as he dared to the border of Frederick’s territory and many of the Wittenbergers hurried off to buy pardons.

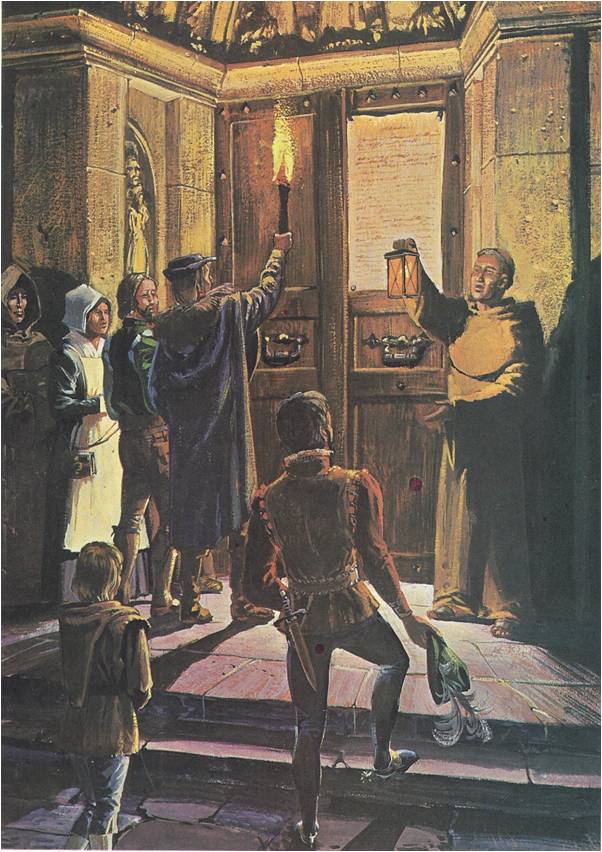

THE NINETY-FIVE THESES

When Luther heard about this, he was horrified and angry. On All Saints’ Eve, the night before the castle relics were to be displayed, he nailed to the door of the castle church a list of 95 theses, or statements. They attacked indulgences in general and Tetzel’s indulgences in particular. These theses were written in Latin, the official language of the Church and Luther offered to debate one or all of them with any churchman or scholar who disagreed with him “These indulgences so praised by the preachers have only one merit.” he wrote. “that of bringing in money. . . Nowadays, the pope’s money-bag is fatter than those of the richest merchants. Why does he not build this cathedral of his own gold instead of the offerings of the poor?”

Luther went on to ask if the pope really had power over purgatory in any case. The Scriptures did not say so. More important, Luther suggested that indulgences might do more harm than good to a man if he forgot about repenting and avoiding sin. A man needed to repent to be forgiven. Luther repeated his own idea of faith and forgiveness: “The grace of Jesus Christ remits the penalties of sins, not the pope.”

As news of the statements tacked to the church door spread across the town, few of the Wittenbergers said that Luther was wrong. Like most Germans, they agreed that the pope was too rich and that his churchmen made use of indulgences merely to collect money. No scholar or churchman offered to debate with Luther.

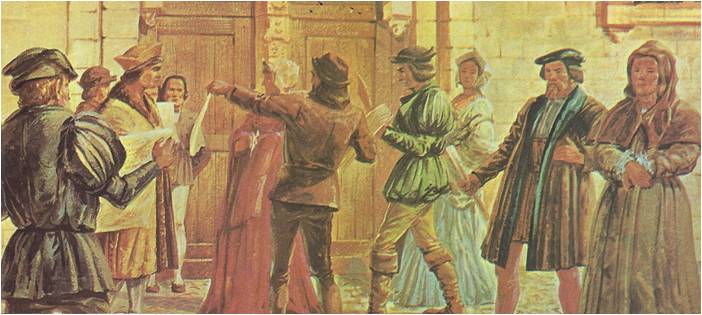

The excitement over the 95 theses might have died down in a few days but someone secretly translated them into German, had them printed and sent copies to other university towns. Suddenly Martin Luther and his attack on the pope’s indulgences became the talk of Germany. Tetzel‚ worried that sales would fall off, wrote a furious answer to Luther’s statements. He and Luther exchanged a series of angry letters. These, too, were printed and eagerly read.

Meanwhile, a copy of the 95 theses had been sent to Pope Leo in Rome. A jovial, easygoing man, Leo preferred poetry to Church philosophy. He liked to live well and disliked quarrels. He looked over Luther’s statements, snorted and decided that one noisy monk could do no great harm to the Church. “He’s a drunken German; when he is sober, he will change his mind,” Leo said — or so the story went in Germany.

The pope’s advisers suggested that quite a number of sober-minded Germans seemed to side with Luther. “Well,” Leo said. “Brother Martin is a brilliant chap. The whole row is due to the envy of the other monks.” Just to be safe, he sent word to the Augustinians that it would be well for them to do something to quiet their outspoken young brother. After all, Luther was saying that Leo was in the wrong in the matter of indulgences. Luther was, therefore, challenging not only the teachings of the Church but also the pope’s authority to interpret them.

The Augustinians were quick to obey the pope’s command. Luther’s superiors demanded that he recant, or take back, his 95 theses. He refused and he refused again when the same demand was made by Cardinal Cajetan, one of the most powerful and clever men of the papal court.

These attempts to silence him aroused Luther’s anger. No longer did he speak out merely against indulgences. He remembered the well-fed monks in Rome and the bishops who lived in splendour like noblemen and nuns who behaved like giddy court ladies. He criticized them all. The news of his defiance spread and more than ever he was the talk of Germany.

THE GREAT DEBATE

Workers, peasants and craftsmen now knew the name of Luther. Noblemen, landowners and knights wrote to him to urge that he speak out more boldly. Germany was restless. Lords and commoners alike were tired of seeing their gold shipped off to Rome and they were angry that one third of Germany’s land belonged to the Church. Luther also began to hear from leaders of German peasant groups, men who hoped to stir up revolt against the old noblemen. Surely, they said, if Luther so hated the pope and the cardinals who robbed the poor of Germany, he must also hate the lords who trampled the impoverished farmers who worked their land. The peasant leaders spoke to Luther of John Wyclif, the churchman who had rallied the commoners of England to battle for church reforms early in the fourteenth century. They reminded him of Jan Hus, who had led the Bohemian peasants in a revolt against the lords of both church and land.

Luther would have nothing to do with revolutions. He did not even think of himself as the leader of a campaign to reform the Church. He was merely a monk and scholar who had, he said, a duty to speak his mind honestly about the problems of the church of which he was a servant. To those who came to him talking of revolt, he said, “I am not willing to fight for the gospel with bloodshed.”

He could not, however, avoid fighting for his beliefs with words. A year and half after he had nailed his theses to the church door, half the people of Germany complained openly against the pope, the Church and bishops were booed in the streets. The worried leaders of the Church decided that Luther must be answered — and in no uncertain terms. His statements must be shown to be wrong. They named another scholarly monk, Johann Eck, as defender of the Church and he called for Luther to meet him in a great debate in the city of Leipzig.

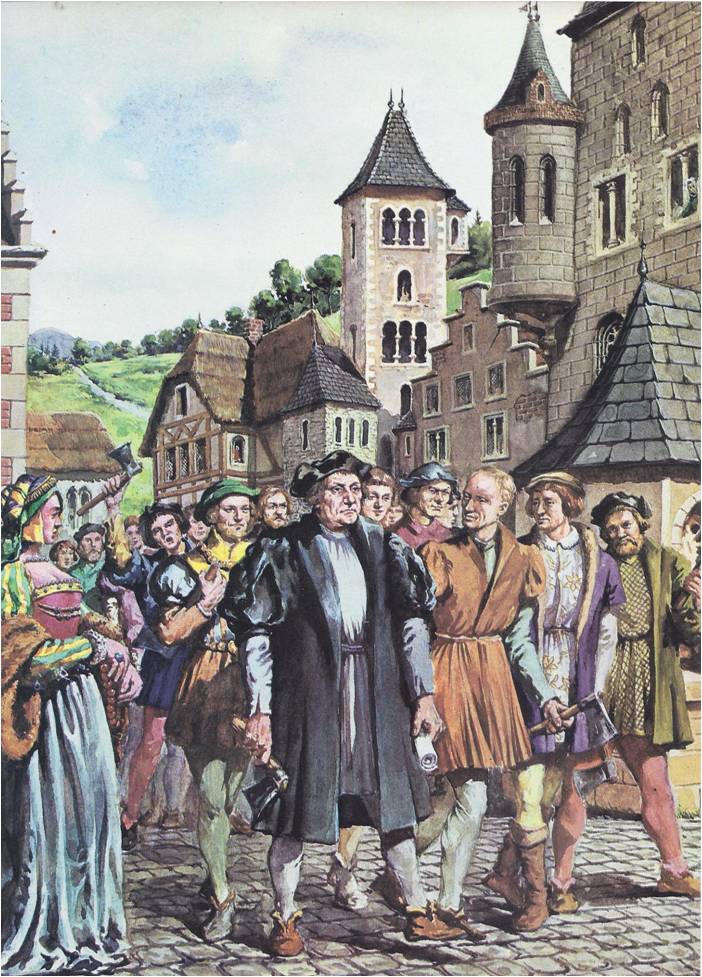

Luther eagerly accepted the challenge. In June, 1519, he strode into Leipzig, followed by a group of his fellow teachers from the university and two hundred students armed with battle-axes. Eck was already in the city. He had no band of shouting students, but the town council voted him a bodyguard of seventy-six men to protect him against the Wittenbergers.

On the first day of the debate, an excited crowd jammed the great hall of the Leipzig castle where the speeches were to be made, but the contest did not begin immediately. The local duke rose to greet the debaters and the crowd. Then for two hours his secretary discussed the rules of the debate. A choir sang to the accompaniment of the town piper and after that, everyone went to lunch. Finally, in the afternoon, the men whom everyone had come to hear were given a chance to speak. Johann Eck listed all the theses of Jan Hus which, he said, Luther had repeated. These statements had been condemned as heresy by a General Council of the Church and Hus had been burned for making them. Luther did not deny that he agreed with some of Hus’ beliefs. Indeed, he said that it seemed that the council had made a mistake when it called these truths heretical.

Eck was delighted. Luther might as well have said that the pope himself had made a mistake. “Are you the only one who knows anything?” Eck shouted. “Is all the Church wrong except for you?”

Luther smiled. “I answer that God once spoke through the mouth of an ass.” Then he said more criously, “I am a Christian scholar, and I am bound to defend the truth . . . . I will be the slave of no one . . . council, university, or pope.”

Eck attacked him again. Luther answered just as hotly. So it went, mornings and afternoons, for eighteen days. The debate, one of the spectators reported, “might go on forever,” but the duke called an end to it. He needed the hall for a ball in honor of a visiting nobleman.

Eck hurried off to Rome to report that the German troublemaker could be punished for speaking heresy. Luther and his followers journeyed triumphantly home to Wittenberg, hailed by crowds at every crossroads. Encouraged by their cheers, he rushed to write more books, pamphlets and letters criticizing the Church.

THE BREAK WITH ROME

While Luther wrote, Pope Leo thought. For a year he pondered the punishment he would name for Brother Martin. It was a difficult decision. He wanted to silence Luther, but he did not want to stir up too much anger in Germany. It would really be best, Leo decided, if he could persuade the noisy monk to be quiet without punishing him at all. In June of 1520, he sent Luther a warning. The monk must recant his statements within sixty days or be excommunicated from the Church.

Luther’s reply was another pamphlet, the most defiant of them all: An Open Letter to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation Concerning the Reform of the Christian Estates. In the pamphlet he outlined a program of revolutionary changes for the Church. This was open rebellion against the pope. When Luther sent the pamphlet to the printer — not in Latin, but in German, so that everyone could read it — he at last admitted, to himself and to the world, that he was the leader and spokesman for the thousands of Germans who demanded church reforms.

So many people rushed to buy the pamphlet that printers in a dozen German cities worked their presses overtime to make enough copies. On other presses another document was being printed, Pope Leo’s Bull of Excommunication. “Arise, O Lord,” it began. “A wild boar has invaded Thy vineyard.” The wild boar was Martin Luther and the pope called on all Christians to drive him from their cities, to burn his writings and to erase his ideas from their minds.

No longer could Pope Leo speak jokingly about Brother Martin. The ideas in Luther’s new pamphlet were too shocking and too dangerous. Luther renounced the authority of the pope. He denied that churchmen had any right or power to speak for God to Christian men or for men to God. Every man was a priest, Luther wrote, if his faith was true and strong. Every man had the right to study the Bible, to seek its meaning for himself; and the words of the Bible, not the decrees of a pope or church council, were every man’s guide to the proper way to worship.

Luther questioned the pope’s power over bishops and priests, the power that made Pope Leo the equal of kings, the lord of an empire that included all of Christendom. He called on the noblemen of Germany to ignore the pope and to appoint themselves as “emergency bishops” in their own territories in order to force the local churches to make reforms. He urged German priests to break their ties with Rome and to form a national Church under the protection of their princes.

BONFIRES OF BOOKS

Pope Leo was disturbed to discover in Luther’s pamphlet a threat to his treasury. If the Church has no right to tell men what to believe, Luther asked, why should it have the right to collect money? He also attacked the time-honoured customs and ceremonies of the Church. The Seven Sacraments, which the churchmen held to be important, were not mentioned in the Bible, he said. He suggested that there should be only three sacraments: baptism, communion and penance.

He added that the giving of alms to the poor was no way to win forgiveness for sins. It might make the giver feel kind-hearted, but it encouraged men to become beggars instead of going to work. Luther asked why priests, nuns and monks should be forbidden to many; there was no such command in the Bible. Indeed the Bible said nothing about monasteries, or masses, or fasting. These things should be forgotten and many more schools should be opened so that all men could read and understand the one thing that did matter in religion, the Bible.

Men had been burned at the stake for writings less rebellious than these. For the moment, Pope Leo had to satisfy himself with burning books. In one German city after another, bishops presided over bonfires fed with copies of Luther’s books and pamphlets. In Wittenberg too, there was a bonfire; but the books were different. In the clearing by the city gates, the students and professors of the university burned the works of Johann Eck and others who were loyal to the pope. Luther himself threw a copy of the Bull of excommunication into the flames. “Since they have burned my books, I burn theirs,” he said. “So far, I have only toyed with this business of the pope.”

Leo, fuming in Rome, called for the cities of Germany to enforce his ban forbidding any Christian to give shelter or safety to Luther. Luther appealed for the protection of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor. The pope, in turn, sent his own message to the emperor: “Obey the commands of the Church.”

The Emperor Charles, though he was barely twenty-one, ruled the largest domain in Europe. He was King of Spain, King of Naples, and Lord of the Netherlands and he had recently been elected to succeed his grandfather as ruler of the Holy Roman Empire, which included all the states of Germany. Young Charles was a loyal Catholic and he should have been friendly toward the pope. The supply of gold in Charles’ treasury was as small as his empire war large. He could not afford to hire armies of professional soldiers; he was forced to depend on the loyalty of his German princes and their knights. To win their loyalty, he had to promise that no German would ever be condemned without a trial in his own country. Martin Luther was of course a German. When he appealed to Charles. the emperor sent his apologies to the pope and agreed to protect the monk until he could be tried. Luther would be condemned, Charles assured Leo, but it would have to be done in a carefully legal way that would satisfy the Germans.

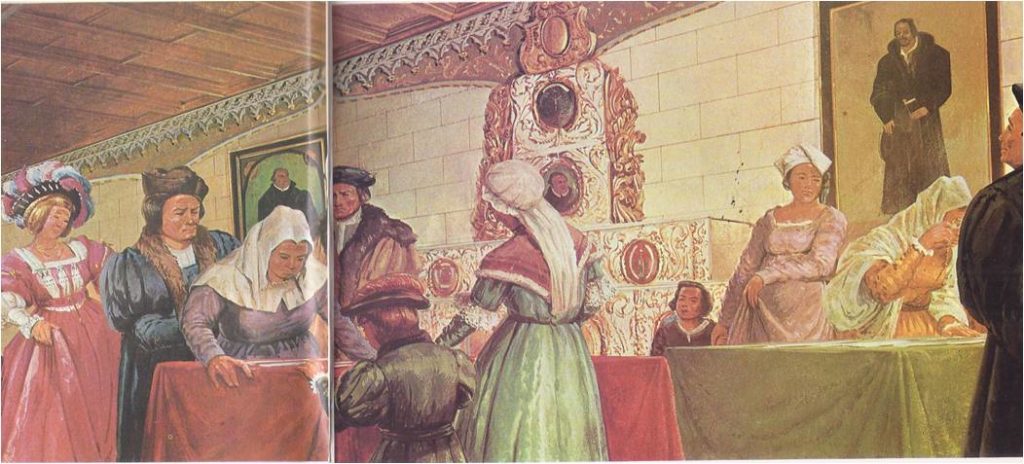

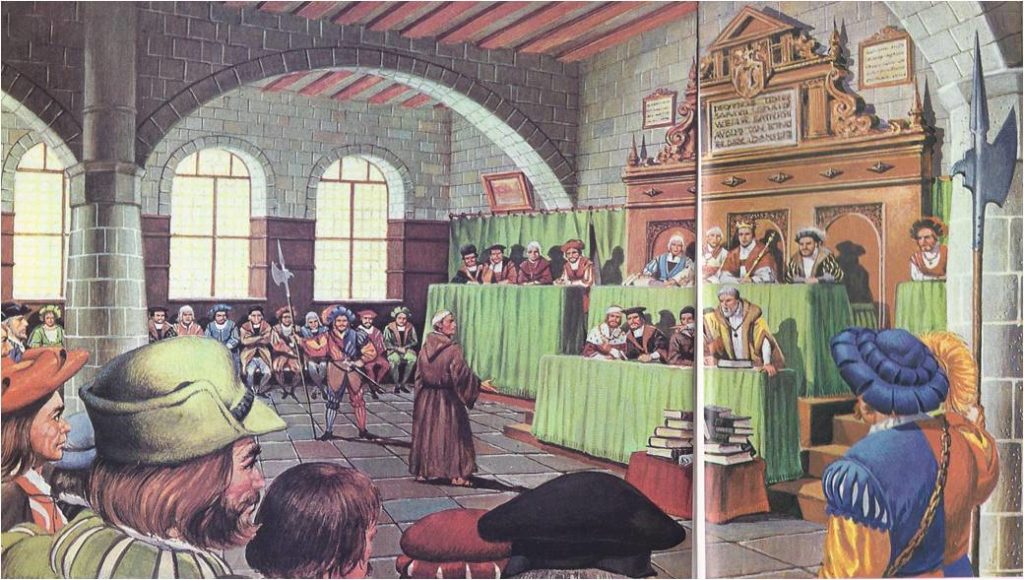

So it came about that in April, 1521, the humble monk from Wittenberg, a penniless preacher whose grandparents had been peasants, was brought face to face with the emperor of half of Europe, the representatives of the pope and the princes of Germany. The princes, members of the German assembly called the Diet, had been named as Luther’s judges. In January they had gathered in the city of Worms and for weeks they wrangled about their right to try the case. After all, some of them said, it was really a church matter. They argued about allowing Luther to speak to them, argued so heatedly that fist-fights broke out in the midst of the assembly. They disputed the emperor’s edict on which they were to vote; it proclaimed Martin Luther a heretic and a revolutionary. Finally, to calm the noblemen who protested that both the edict and the trial were unfair, Charles V agreed that Luther should appear before the Diet. Charles granted him a “safe conduct.” an official promise that he would not be arrested or punished while he was in Worms for the trial.

THE DIET OF WORMS

On April 16, Luther and a few of his friends rode into the city in a shabby two-wheeled cart, preceded by a herald wearing a cloak marked with the imperial eagle. A cheering crowd of 2.000 persons greeted them. The following day at four o’clock, Luther was conducted to the meeting-hall. Pale and thin from overwork, in his rough monk’s robe he looked like someone of no great importance. He stared at the men who had come to hear and judge him. They were powerful, confident, well-fed men in gowns of velvet and Silk — an emperor, princes, noblemen, burghers and dignitaries of the Church. The Emperor Charles, staring back at Luther, exclaimed with a laugh, “This fellow will never make a heretic of me!” Luther was afraid.

The accuser, an archbishop chosen by the pope, pointed to a heap of books and pamphlets and asked the monk if he had written them. Luther looked at them a moment, then replied in a voice that was almost a whisper, “The books are all mine, and I have written more.”

“Do you stand behind them all,” the archbishop asked, “or do you wish to reject some or parts of them?”

The hall was silent, for in answering this question Luther would save or condemn himself. If he rejected some of his statements, if he recanted, he could escape punishment as a heretic. If he did not, he would call down upon himself the anger of the emperor as well as that of the pope. For months Luther had been certain of his answer, but in that moment of silence, as he scanned the faces of the men who held so much power and authority, his courage wavered. “To say too little or too much‚” he said softly, “would be dangerous. I beg you, give me time to think it over.”

The emperor granted him one day of thought. Luther was taken back to his lodgings and through the night he wrestled with his fears and doubts. Always he had been sure that he was right; but how, he asked himself, could he know for certain? Perhaps the Church did speak for God on earth. Luther’s friends sent him messages, pledging their support, repeating their belief in him and urging him to stand fast. These words were of little comfort to the monk who wondered now if he had not always been too ready to listen when men praised him and his ideas.

Another, larger hall was chosen for the meeting of the Diet the next afternoon, yet the room was so jammed that few persons besides the emperor had space to sit down. Luther kept the crowd waiting until nearly six o’clock. Then, his answer ready, he came into the ball. When he spoke, his voice rang out so that all could hear: “If I am shown my error, I will be the first to throw my writings into the fire” and he asked his accuser to prove that his books disagreed with the Bible.

All heretics, said the archbishop, imagined that they were the only men who understood the Bible, but Luther’s imaginings did not matter in any case. He had not been invited to dispute about the Bible, but to answer one question: would he or would he not recant?

Until now, the trial had been conducted in Latin, but Luther gave his answer to the archbishop’s question in German. As he did so, he glared at the German noblemen, for his words were for them. “My conscience is captive to the Word of God,” he said. “I cannot and I will not recant anything, for to go against my conscience is not right nor safe. God help me. Amen.”

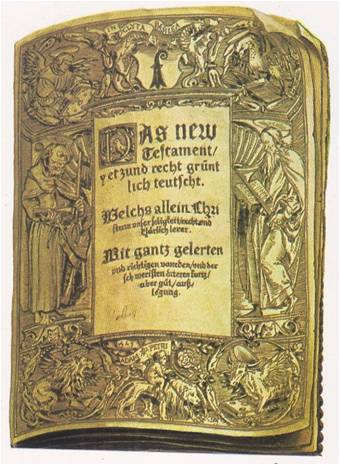

THE BIBLE IN GERMAN

Before the Diet voted on Luther’s case, there were more weeks of angry debate. Many noblemen, impressed with the monk’s ideas or his courage, spoke up for him. In the end, however, Charles V had his way. The Diet found Martin Luther guilty of heresy. Now he was banned by the emperor and the princes of Germany. His punishment was certain — if he could be found to be punished.

For Luther had disappeared. After making his statement to the Diet, he had hurried to ride away from Worms while the emperor’s “safe conduct” still held good. On the road, he and his friends were suddenly surrounded by a band of masked horsemen who rode out of the woods. The bandits had taken Luther away with them and he had not been seen since.

Actually the bandits were servants of Frederick the Wise, the prince who ruled Wittenberg. Frederick, Luther’s friend, now his protector, had planned the kidnapping. He ordered his men to carry Luther to Wartburg Castle, a lonely and ancient fortress. Whether Luther liked it or not, he had to stay there, safer out of the way of the soldiers of Charles V.

For nearly a year Luther lived in the all but empty old castle. He put aside his monk’s robe and dressed as a knight and to add to his disguise, grew a beard. Once in a while messengers came from Wittenberg, but for days and sometimes weeks Luther saw no one except the handful of servants who looked after the fortress. He grew weary of silence and the lack of companions. “I had rather burn on live coals than rot here,” he wrote to one of his friends.

At least he had time for work and he began a mammoth project, a translation of the Bible into German. Such translations had already been made, but they were clumsy and dull. Luther set out to bring the Bible to life by putting it into the language his fellow-Germans spoke every day. So successful was Luther’s translation that it became the basis of the modern German language.

While Luther was hidden away in Wartburg Castle, Germany did not forget him. Despite the pope’s ban, his books about the Church were being printed and read everywhere. Despite the emperor’s annoyance, the ideas in the books were being put into action. A number of priests began to say the mass in German instead of Latin and some were offering the holy bread and wine to the congregations of their churches, a thing that had not been allowed for centuries. Many monks gave up their fasting and penances left their monasteries and went out to preach Luther’s doctrine that men were saved by faith alone. Other monks — and nuns, as well — gave up their vows in order to marry.

As students, merchants, craftsmen and other townsmen joined the Lutheran cause, the people of many cities became split into two feuding groups: the reformers and those who believed in the old ways. Arguments and street-fights became common. Some of the reformers marched into churches to break the windows and lamps and smash the sacred statues. Wittenberg was plagued by a series of riots. When the Lutheran leaders proved unable to control their rowdy followers, Frederick the Wise threatened to outlaw any new reforms. The city councilmen, most of whom favored the Lutherans, decided to take a drastic step. Without telling the prince, they sent a message to Wartburg Castle inviting Luther to return to Wittenberg.

THE NEW CHURCH

In the first week of March, 1522, Luther came home to the city. It was an act of courage, for he was still under the ban of the emperor and the pope and Frederick the Wise had said that he could not protect him if he left the castle. Luther ignored the danger because he hoped to quiet the mobs before their rioting turned other, soberer Citizens against the cause of reform. In Wittenberg he immediately went to his church, climbed to the pulpit and preached a sermon about patience and consideration. Men should be allowed time to think, he said; they could not be forced or beaten into new beliefs. “I took three years of constant study, thought and discussion to arrive at my conclusions and can the common folk, untaught in church philosophy, be expected to come as far in three months?”

Order was restored in the city and Luther turned again to his writing. Neither the pope nor the emperor interfered with him, for they were involved in wars with each other and the king of France. When they had settled their quarrels, the Turks kept them busy with threats of invasion from the East. It gave Luther the freedom and the time to guide the revolution he had helped to start, the revolution that was coming to be called “The Reformation.”

By 1524, nearly half the people in Germany had joined the reformers. They called their way of religion Lutheran, though Luther himself preferred the name Evangelical, which means “Missionary.” Whatever its name, the new church had surprising power and wealth. It had the support of many German princes, knights and the riches of deserted monasteries whose lands and treasures the Lutheran noblemen claimed. The reformers desperately needed leadership. Too often their efforts led only to confusion. Lutheran priests and monks wandered about Germany, each of them preaching his own version of Luther’s ideas. There were new outbreaks of rioting and church-wrecking. Struggling to set things in order, Luther sometimes lost patience with his most eager followers. When they doubted or questioned his ideas, he exploded with rage. He seemed to believe that he had discovered the one true path to heaven and almost to have forgotten that he had proclaimed the freedom of Christian men to think for themselves.

The peasants of Germany, however, had not forgotten. To Luther, this freedom meant only each man’s right to worship God in his own way. To the peasants, it also meant freedom from the lords who owned the lands they worked, sold the crops they grew and forced them to live in poverty. As the Church revolution spread, there was more and more talk of a revolt against the noblemen.

Late in 1524, the peasants of southern Germany finally rose up and marched to battle. Their leaders were certain that Luther would side with them and for a time he did. When he found that the peasants were as interested in political freedom as in religious reform, he switched his support to the nobles. His plans for reform, he said, were for the Church, not the government and in any case there was no place in them for brawling peasant toughs. In a fiery pamphlet he urged that the revolutionists be put down, saying, “Nothing can be more devilish than a rebel. It is just as when one must kill a mad dog; if you don’t strike him, he will strike you and the whole land with you.”

THE LUTHERAN LORDS

The noblemen did strike. Their well-trained armies crushed the ragged bands of peasants and overran their strongholds. Thousands of peasants, women and children as well as men, were slaughtered. Again Luther published a pamphlet; this time he condemned the nobles for their senseless cruelty. Somehow this pamphlet was soon forgotten. When the fighting came to an end in 1528, the peasants still blamed Luther for betraying the revolution — and the Catholic noblemen blamed him for starting it.

Fortunately for Luther, his support of the nobles had won many of them to his side, enough to protect the new church in Germany. At a meeting of the Diet in 1526, these Lutheran lords passed a law that each German state should be allowed to decide for itself whether it wished to continue the ban against Luther’ s ideas. Three years later, when the Emperor Charles V tried to force the Diet to cancel the law, nineteen German princes stood up to him and protested. Since each lord had a state at his command, the emperor changed his mind. For one year, he said, the Germans could be Lutherans if they chose. After that, however, they must come back to the church of the pope or be forced back by soldiers of the imperial army.

THE PROTESTANTS

A year passed and the imperial army was too busy fighting Turks to make the Lutherans return to the Church. Indeed, seventeen years went by before Charles V tried to enforce his decree. By that time the reformers were strong, well-organized and they had a new name, Protestants, in honour of the nineteen princes who had protested to the emperor.

Luther was the leader of the Protestants, but he led a much quieter life in the years that followed the peasant uprisings. He had come to fear disorder as much as he had once feared the anger of God. He took pleasure now, not in Church revolution, but in the changes that came to individual men and women as they turned to his way of worship. No longer did they buy indulgences, or make pilgrimages to peer at relics, or try to pay for their sins by giving alms. Like Luther, they knew that they were men and therefore sinful, but they were unafraid and believed that they would be saved by their faith in the mercy of God, the God they learned to know by reading their Bibles. In thousands of German homes, families studied the Bible for themselves and most of them read the translation Luther had written.

Luther now had a family of his own. When he had been hiding at Wartburg Castle and heard that the monks had begun to marry, he had laughed, “Good heavens! They won’t give me a wife.” A few years later, in 1525, one of his friends received a delighted note: “Come to my wedding. I have made the angels laugh and the devils weep.” Luther’s bride was Katherine von Bora, a young woman who had sought the protection of the Lutherans in Wittenberg when she and a group of nuns escaped from their convent in a wagonload of empty herring barrels. Luther found husbands for her friends and for two years tried to find a husband for Katherine before it occurred to him that he really wanted to marry her himself. They raised a large family. They had six children of their own and adopted four orphans, not to mention an assortment of student boarders they took in to earn money for food. In this crowded, bustling household, Luther somehow got on with his writing and reading. He found time to chat and play with his children and time, too, for the music he loved. He wrote many hymns, such as A Mighty Fortress Is Our God and, for the children’s Christmas, Away in a Manger.

The happy times did not last. In his sixties, Luther was tormented by illness. The monastery years, when he tortured himself with fasting and penances and the years of reform, when he worked too hard and slept too little, had left his body weak. Sickness made his temper flare up and sometimes he felt the old terror and doubt: had he, after all, been right to defy the Church? On days when he was himself again, it annoyed him that he could not preach and work. Now he defied his doctors, instead of the pope and left his bed in order to write or to meet with the new leaders of the Lutherans. In 1546, he was asked to settle a dispute between two noblemen. He was too ill to make the journey to the noblemen’s castles, but he went anyway and on the way home, he died.

Once, when he had stood in danger of being burned as a heretic, Luther had said that he was ready to die: “I have lived enough. Not until I am gone will they feel Luther’s full strength.”

THE PEACE OF AUGSBURG

The Power of Martin Luther was indeed felt after he was gone. A few months after his death, Charles V turned the might of his empire against the Lutherans of Germany. For nine years his soldiers tried to beat them into submission — and into the old church of the pope. The soldiers failed and the Protestant princes forced the emperor to a truce, the Peace of Augsburg. It was agreed that henceforth two churches would be allowed in Germany, the Catholic Church of Rome and the Evangelical Lutheran Church. It would be upto the prince of each state to decide which of the two ways of worship would be practiced in his own territories.

So the new church stood firm beside the ancient one, only 38 years after Luther had nailed his theses to the door of the castle chapel in Wittenberg. In that short time, thousands of men and women had joined the struggle for a reformation. Although they had long complained about the old church and its leaders, it was Luther‘s example of independence and daring that gave them the courage to act. In spite of himself, the scholarly monk had begun a revolution.

It was a time of revolution and change, a time when men were learning to think for themselves and not only on questions of religion. They were also learning to think together as nations. The old Holy Roman Empire, like the old papal empire of Christendom, was too big; its many different peoples — Germans, Italians and the rest — could not be united. On the other hand, the dukedoms and baronies of the lords were too small and week to protect their citizens properly. In Germany, a country split into many such little states, men felt the need to be united as Germans. When Luther called on them to break their ties with Rome, he helped free these German from the empire that was too big. At the same time in winning the support of the princes and town councils for his new church, he made it a national church that helped hold together the people of the small German states.

In other countries‚ the reformation of religion also became a part of the pattern of change. The people of Scandinavia broke with Rome and founded Protestant churches sponsored by their states in France, Switzerland, the Netherlands and England, men followed many new leaders –preachers, scholars and writers whose ideas were not always the same as Luther’s. They all respected Luther’s courage and honored his memory. Nearly all agreed with him that a man must be free to seek God for himself, in his prayers, in his Bible and in his heart. It was not enough to keep a promise to Saint Anne — only by faith could a man escape the lightning and thunder of heaven.