IT WAS COLD INSIDE the great cathedral of St. Peter in Rome on Christmas day, in the year 800. The breath of the closely packed worshipers rose like steam. Although their heads were bowed in prayer, many of the worshipers stole a quick glance at the man kneeling near the high altar. He was tall and heavy, with fair hair and a flowing mustache; he was dressed in a simple tunic and a fur-trimmed cloak.

When the devotions came to an end, the tall man started to rise. At that moment, Pope Leo III, Splendid in his gold-encrusted vestments, stepped forward quickly. Placing a gold Crown on the tall man’s head, the pope said in a loud voice, “To Charles Augustus, crowned of God, great and pacific emperor of the Romans — life and victory!” The crowd in the cathedral cheered‚ just as Roman crowds had cheered so many times in the past at the coronations of the Caesars.

The new emperor was no Caesar; in fact, he was not even a Roman. He was a German and the king of the Franks. His name was Charles and at the time of his coronation he was called Charlemagne, which meant “Charles the Great” in French. Charlemagne was born in the year 742, the eldest son of Pepin the Short and the grandson of Charles Martel. In 752, when Charlemagne was ten years old, his father became king of the Franks. Charlemagne and his younger brother, Carloman, were proclaimed King Pepin’s rightful heirs and after Pepin died in 768, his realm was divided between them. Carloman died three years later and Charlemagne was sole ruler of the Franks.

He immediately began the first of the many wars that marked his reign. Altogether, he conducted fifty-four campaigns — against the Lombards, the Saxons, the Frisians and Danes, the Avars, the Slavs, the Gascons, and the Moslems in Spain and southern Italy. Charlemagne waged so many wars that a chronicler was careful to point out that the year 790 was exceptional. “This was a year,” the chronicler wrote, “without war.” Charlemagne made war for several purposes: to extend or defend his lands and to convert the heathen to Christianity.

CHARLEMAGNE’S WARS

For his first campaign, against the Lombards in northern Italy, Charlemagne had a perfect excuse. The king of the Lombards had attacked some cities which were held by the pope, even threatening Rome itself. Pope Hadrian appealed to Charlemagne for help. The pope reminded him that King Pepin, Charlemagne’s father‚ had pledged eternal loyalty to the Church and the pope, promising to protect them against all enemies. Charles answered Hadrian’s appeal by crossing the Alps and attacking Lombardy. The Lombard army, outmatched by Charlemagne’s well-disciplined troops, retreated behind the stone walls of their capital, Pavia. Charlemagne besieged Pavia for nine months until the Lombards were starved into surrender. While the siege was still going on, Charlemagne made an Easter pilgrimage to Rome, becoming the first Frankish king to enter the city. Although he received a tumultuous welcome, he went up the steps of St. Peter’s like any ordinary pilgrim — on his hands and knees. At the top of the stairs, Pope Hadrian lifted him up and embraced him.

After conquering Lombardy and sending the deposed king into a monastery, Charlemagne turned his attention to Bavaria, in what is today southeastern Germany. Bavaria was ruled by warrior dukes who strongly objected to paying homage to Charlemagne as their king and overlord. They did not object for long. Charles defeated them in battle, deposed their leader and claimed the territory as part of his empire.

One of Charlemagne’s most important accomplishments was the conquest of Saxony, in east and northeast Germany. It took him twenty-three years of bloody and savage fighting to subdue the fierce, pagan Saxon tribes. For many years they had crossed the Frankish borders, raiding towns, plundering monasteries and looting farms, then melting back into the countryside before they could be captured.

The Saxons worshipped trees and streams and often sacrificed human beings to their bloodthirsty gods. They were determined to remain pagan and Charlemagne was equally determined to convert them to Christianity. Time after time he would defeat their armies, forcing the leaders to accept his authority and give hostages. He would establish garrisons and bring in missionaries. Soon after he had moved on, however, the Saxons would revolt, massacre the garrisons and murder the missionaries. Finally Charlemagne beheaded hundreds of the Saxon leaders, deported thousands of Saxons to Frankish territory and colonized Saxon lands with his own people. He issued a stern edict that gave the Saxons their choice of accepting Christianity or death. Alcuin, the great English scholar at Charlemagne’s court, bitterly criticized these harsh actions, but Charlemagne did not change his policy. He was determined to bring all of western Europe under his rule and make it obedient to the authority of the Christian church.

THE SONG OF ROLAND

Charlemagne’s only real military defeat came in Spain. One of his dreams was to push the Saracens, or Moslems, in Spain farther south and convert the northern part of the country to Christianity. In 778 he led two armies over the Pyrenees Mountains. He attacked the Spanish city of Saragossa but failed to capture it. During the siege of the city, he was called home to put down one of the many Saxon revolts. He set out with the main body of his army, protected by a rear guard under the command of his friend Roland, the governor of Brittany and a fine warrior.

When Roland and his men marched through a mountain pass near Roncesvalles, they were ambushed by a Basque army. The Basques were a fiercely independent people who lived on both sides of the Pyrenees. Although badly outnumbered, Roland refused to blow a blast on his horn — the signal that would call back Charlemagne and the main body of the army. He felt it was a matter of honour for the rear guard to protect the troops heading north. Roland’s heroic battle became a legend and was the subject of a Poem called The Song of Roland, an important work in French literature. The epic poem tells how Roland wielded his sword with superhuman strength as he and his men bravely fought the Basques. At last Roland blew a blast on his horn, summoning Charlemagne. Traitors tried to delay Charlemagne and he hesitated. Then the horn sounded a second time and Charlemagne rushed to the rescue but it was too late. Roland lay dead and the Basques had escaped.

THE SPANISH MARCH

Years later, Charlemagne returned to Spain and established a powerful military base, known as the Spanish March. This was one of many military “marches” that formed a ring around the borders of Charlemagne’s empire. With the defeat of the Avars, who lived east of the Danube River and the Czechs and the Danes‚ who lived in northern Europe, Charlemagne dominated almost the whole of Europe. Except for the Scandinavians far to the north and the Angles and Saxons who had managed to escape to Britain, Charlemagne had brought all the Germanic peoples into one united nation. When he was crowned by Pope Leo III in 800, he became the emperor of what would later be called the Holy Roman Empire.

Charlemagne was more than a conqueror; he was a wise and just ruler. He set up a system of relief for the poor, supporting it with taxes paid by the nobles and the clergy. Unlike earlier warrior kings, he valued culture and learning. He was particularly interested in education. He encouraged churches and monasteries to set up schools and told the directors to “take care to make no difference between the sons of serfs and of freemen, so that they might come and sit on the same benches to study grammar, music and arithmetic,” although he himself did not learn to read or write until late in life. His secretary noted that Charlemagne “used to keep tablets under his pillow in order that at leisure hours he might accustom his hand to form the letters; but as he began these efforts so late in life, they met with ill success.”

Charlemagne welcomed scholars from everywhere in Europe, putting some of them to work at translating old texts and copying manuscripts. He brought in books from other countries and set up a school of his own. He attended the school himself, along with his wife, his sons, his daughters and his secretary. The palace school, as it was known, was open to the children of government officials, nobles and to any other promising children brought to Charlemagne’s attention.

A devout Christian, Charlemagne took a deep interest in the Church. He kept a sharp eye on the clergy. He expected them to be faithful, dedicated men, following the strict rules laid down by Pope Gregory I and St. Benedict, the founder of the order of Benedictine monks.

Charlemagne issued many laws for the Church — laws concerning property, buildings, discipline, education and ritual. To make sure his wishes were carried out, he sent missi dominici, or royal messengers, throughout the land. They reported directly to him everything they saw and heard. According to ancient records, Charlemagne ordered his royal messengers “to investigate and to report any inequality or injustice . . . to render justice to all, to the holy churches of God, to the poor, to widows and orphans and to the whole people.” He also warned them “not to be hindered in the doing of justice by the flattery or bribery of anyone, by their partiality for their own friends or by the fear of powerful men.”

In contrast to later kings, who would govern from a palace in a capital city, Charlemagne had no formal capital. He was constantly on the move. When he was not on a military campaign, he travelled from one royal estate to another. With him moved his court, made up of hundreds of people — courtiers, advisers, soldiers, scholars, clerks, clergy, cooks and servants. Wherever they went, they had to have food and shelter. This was something of a problem, for there were no public accommodations and towns were far apart. Although Charlemagne owned lands in many parts of his kingdom, often he and his court would stay with one of his vassals — the noblemen who had sworn an oath of loyalty to him. Such a visit was a great honour, but sometimes the expense of putting up so many people left the honoured nobleman close to bankruptcy.

LORDS AND SERFS

Wealth in Charlemagne’s time was drawn almost completely from the land. The king and the nobles controlled vast estates, much as they had in the last days of the Roman Empire. Part of the estate was set aside for the use of the lord; part was farmed by tenants. These tenants called themselves freemen, but they were little better off than the serfs, for they had to serve both their lord and the king. They were required to work the lord’s fields, to make certain payments of money to him and to do various other services for him. In addition, they could be called up at any time to fight in the king’s army. To escape so crushing a burden, many freemen voluntarily became serfs. In this way, society began to move toward the system that would become known as feudalism.

Without realizing it, Charlemagne himself helped to break down the unity he had so carefully built up. It was his practice to reward his loyal followers by giving them lands worked by serfs. These followers became lords of their own lands and could do what they pleased with them; often they gave some of their lands and serfs as a reward to their own followers. While Charlemagne lived, it seemed as though his empire would endure for ages, but within a few years after his death in 814, it began to fall apart.

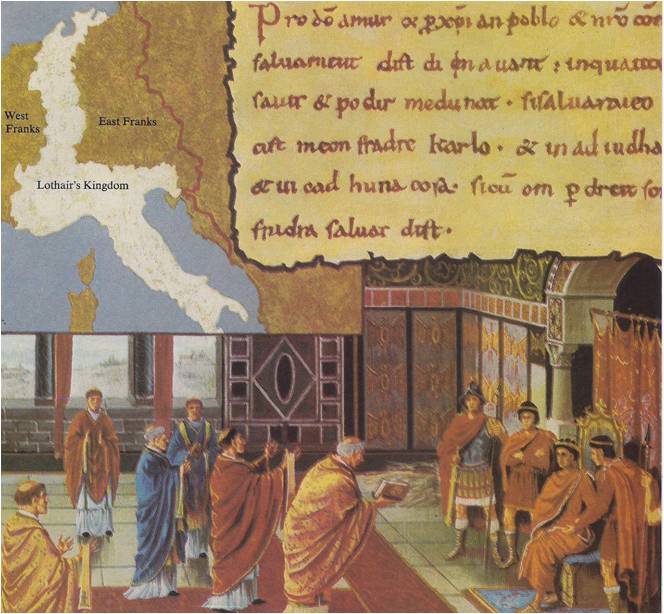

Charlemagne’s power passed to his son, Louis the Pious, who brought back an old custom and divided his empire among his three sons. Each of them was dissatisfied with his portion and they promptly began quarreling among themselves. The eldest, Lothair, revolted against his father and for a time deposed him. When Louis died, the two younger brothers, Ludwig and Charles, allied themselves against Lothair, who claimed the title of emperor.

After two years of warfare, the brothers negotiated a peace and signed the Treaty of Verdun. Lothair was given the title of emperor and a kingdom carved out of the middle of the empire; it included Rome and the northern half of Italy. Ludwig received the region to the east, called the East-Frankish kingdom. Charles received the region to the west, called the West-Frankish kingdom. The East-Frankish kingdom would many centuries later become the nation called Germany, the West-Frankish kingdom the nation called France; the middle kingdom would remain a troubled area and be fought over for centuries to come.

With the Treaty of Verdun, Charlemagne’s great empire came to an end; ended, too, was any hope for a united Europe. Once again Europe was a divided land.