For thousands of years during the Stone Age, only scattered groups of people had lived in India. With only the simplest tools of bone, wood and stone, they hunted and gathered food. Cut off from other peoples by the mountain and the sea, the first Indians made few advances in their primitive way of life. Then, sometime between 3500 B. C., new settlers began to appear along the Indus River Valley in northwestern India, a region that would be called West Pakistan thousands of years later. It seems almost certain that these newcomers were from the mountains and plateaus to the northwest, the modern lands of Iran and Afghanistan.

When they arrived, the new commers were already able to make pottery, to farm and to raise animals. Most likely too, some of them knew of the cities far to the west, on the plains of Mesopotamia. From those more advanced cities, the Indus valley people learned about new objects, such as copper and bronze tools. They also heard tales about how those distant peoples controlled the river’s water, or how they scratched signs in clay tablets to record words. However much they may have borrowed, the Indus Valley people worked out their own ways. By 2500 B. C., a distinctive civilization had begun to develop along the Indus River.

The river itself played an important part in this civilization. Sometimes it flooded so badly that it wiped out villages and fieldworks, or even changed its course entirely. Usually however, it overflowed just enough to leave a rich soil for each season’s crops and the people worked together to take advantage of it. The river also made it easy for the various settlements to exchange goods and ideas.

The People of the Indus

Of the dozens of villages, two soon grew larger than the others and became the centres of their regions. Far up the river was Harappa, with its great citadel and grain stores. Down river was the equally important city of Mohenjo-Daro. Led by these cities, the Indus Valley people shared a way of life that was truly flourishing about 2000 B. C.

This civilization had little effect beyond the one small corner of northwestern India. Most of India was still inhabited by half-wild tribesmen who had little or no contact with each other. It was to be many centuries, infact, before there was any real unity among the people of India, largely because of the geographic barriers. India was divided by a variety of landscapes and climates ranging from desert to jungle. The only condition common to all of India was the annual rainy season, which lasted from May to September.

There was a great difference between northern and southern India and this was to have enormous influence on India’s history. The north had variety in its terrain, but all its regions had atleast some contact with each other. Across the far north were the forested slopes of the Himalayas. Spreading down from them were the northern plains, fertilized by the rivers from the Himalayan snows. Then came the great central plateau and across its southern-edge ran the Vindhya Mountains, which almost cut India in two. Below these mountains was southern-peninsular India, a world apart.

One of the things that set southern India apart from its north was its semi-tropical climate. Even more important was the isolation forced on the southern peoples by the Vindhya Mountains. The southerners came to be called Dravidians, after the language they spoke – a language totally unrelated to that of the northerners.

The Dravidians were largely unaffected by the Indus Valley Culture and kept up their own religion and social customs. In time, however, they came into contact with the northerners through trade; the northerners were anxious to buy gold, pearls, conch shells, spice and other rare products from the south. Even so, it was a long time before the Dravidians became a part of Indian civilization and some isolated tribes did not change their ways until modern times.

By 2000 B. C., the Indus valley people were thriving. They raised barley and wheat as their basic crop and grew cotton to be woven into cloth. Herdsmen tended the large humped cattle that provided food and drew the wagons. Hunters hunted animals such as the tiger, the rhinoceros, the crocodile and the elephant, as well as smaller game. Along the river, men loaded rafts with produce to be traded in the Persian Gulf or to be paid as taxes to Mohenjo-Daro.

Mohenjo-Daro was hardly a centre for luxury, but it was a prosperous and splendid city for its day. Like Harappa, it was dominated by its great walled citadel, built on a mud-brick platform many feet high. Within the citadel were the fine buildings of state and ceremony, including the Great Bath, made of stone and used as a pool in certain rituals. Also in the citadel was the large civic granary, where the harvest was stored in well-ventilated chambers. No one thought it was strange to have the granary in the citadel, for the entire life of the community depended on the crops.

Below the citadel was the residential quarter of Mohenjo-Daro, where people went about their daily tasks. Women drew water from the many wells, while along the streets workmen cleaned debris from brick-lined drains. Metal-smiths made axes, knives and saws from copper and bronze. Skilled craftsmen cut delicate figures of animals into small square stones that would be pressed into clay seals. Some seals had words printed in a script made by the Indus valley people, although they probably borrowed the idea from the Sumerians of Mesopotamia.

All the houses were of plain design and made of mud-brick, but those of the wealthy had pleasant courtyards and staircases to upper stories. The most remarkable feature of Mohenjo-Daro residential quarter was its careful planning. Streets crossed each other at almost perfect angles and buildings were arranged in blocks of more or less the same size.

Such organization did not mean that the rulers kept the people regimented by force, nor that they had to use force to unify all the Indus valley settlements. As did other civilizations that grew up long the rivers, the Indus valley people found it easy to share their way of life. They believed that their rulers were responsible for the welfare of the community and that the gods were responsible for the fertility of nature. To keep harmony in this world, the people could also respect the need for an orderly city.

The Coming of the Aryans

As the centuries passed, however, the Indus valley settlements began to decline. Perhaps they exhausted their resources by letting their population grow too fast; perhaps they had become too fixed in their ways and no longer changed with times. Then, about 1500 B. C., Mohenjo-Daro was attacked. It was a sudden raid, for some people were struck down in the streets and in their homes. Mohenjo-Daro was left forever deserted.

It is likely that the raiders of Mohenjo-Daro were the Aryans, the people who began to appear in northern India about this time. No one knows the original homeland of the Aryans; perhaps it was in central Asia or even far north near Scandinavia. For hundreds of years various tribes of Aryans wandered about parts of Europe and Asia. Although their name meant “kingsman”, most of the tribes had long ago lost touch with each other. Their languages were related, however and they shared the way of life of semi-nomadic warriors and herdsmen.

Whatever their original homeland, the Aryans who appeared in India were close relatives of those who had earlier settled to the northwest in the land of the Aryans, or Iran. The Aryans did not sweep across India and wipe out everything in their path. They took many years to move gradually eastward and spread along the river basins of northern India. During this time, some of the native people resisted and some retreated, but finally they had to go on living with their conquerors. Later as the two peoples mingled, each influenced the other’s way of life.

The Aryans set themselves up as an aristocratic warrior class and the settled peoples were forced to work for them. Although they did some farming, the Aryans preferred to raise cattle, sheep and goats for their food. They could also tan leather, work metals and weave cloth. Most of all, the Aryans liked to go out to raid and to battle, seizing booty or demanding treasures or food as tribute. They rode forth in two-wheeled chariots drawn by two horses, with a charioteer crouching low between two warriors armed with spears or bows and arrows.

For hundreds of years, the Aryans in India kept up their old ways. They did not even build cities, but lived in wooden houses in fortified villages. They had small assembly halls, where the elders discussed the affairs of the tribe, while the young men held chariot races outside the village. The Aryans enjoyed music, feasting and dancing. Their favourite drink was soma, an intoxicating juice from a plant and one of the men’s favourite pastimes was gambling with dice. Not everyone approved of gambling as shown by a song that said:

My wife rejects me and her mother hates me.

The gambler finds no pity for his troubles.

It was not surprising that the Aryans worshipped Indra, the powerful god of thunder and battle, although Indra was only the most important of the many gods they worshipped. Most of the gods were forces of nature, such as Agni, the fire god, or Varuna the sky god. To show their devotion to the gods, the Aryans held many ceremonies around their altars. Often they sacrificed animals. Prominent in the ceremonies were their prayers and hymns in which the gods were asked to fight off evil and to do good for the worshippers.

For many centuries these hymns and prayers were passed on from generation to generation by the priests who chanted them at the ceremonies. Finally some learned priests decided to write them down in the Sanskrit language. They collected more than one thousand of these hymns in a book called the Rig-Veda. Many were extremely beautiful and expressed the Aryans’ devotion in simple language. One of the finest was the Hymn to the Dawn:

Arise! the breath, the life has reached us.

Darkness has gone away and life is coming.

She leaves a pathway for the sun to travel:

We have arrived where men prolong existence.

The Rig-Veda was one of the four books that made up the Veda, a title that meant “knowledge”. The Veda was the Aryans’ traditional and religious wisdom, much of which had been passed on for centuries by word of mouth before it was written down. The Veda included not only religious hymns and prayers, but still older folklore, such as spells and charms. Not all the Veda was fine literature, however, and much of it was difficult for anyone except the priests to understand. As the centuries passed, the priests also added passages in prose, such as commentary on the rituals and laws. Later, too, they added the sections of profound philosophy called the Upanishads.

The Veda was to have a great influence on Indian thought and culture, but when first set down, it meant little except to a few people along the northern river valleys. There, by the year 1000 B.C., great changes were taking place. When the Aryans first appeared, for instance, their families were grouped into tribes, each governed by an elected Rajah and a tribal council. As the Aryans became more settles and grew in numbers, the tribal groupings developed into city-states and kingdoms. Although these expanding kingdoms sometimes fought each other, they brought some order to the land.

Meanwhile there had been a gradual shift of people and power to the east and south of the Indus valley. Along the Ganges and Jumna rivers, many settlements grew up in the years between 1000 and 500 B. C. Some, such as Kaushambi and Rajagriha, became great cities with strong defenses. In central India there was Ujjain, a sacred city with fine buildings of stone and paved streets. In the northeast, the Magadha Kingdom began to grow powerful; it was to be the centre of many important religious and political forces.

The Rise of Hinduism

By 1000 B. C., the pre-Aryan and Aryan cultures had also begun to blend. Out of this mixture was to come the classic Indian civilization. The Aryans continued to lord it over the pre-Aryan peoples, but, through the centuries, the Aryans were also influenced by the pre-Aryans. The heroic tales and legends of both peoples led to the creation of the great Indian epic poems.

One of these was the Ramayana, a long poem said to have been composed by the poet Valmiki about 550 B. C. It was written in the Sanskrit language and told of Prince Ramayana, who was driven into exile by his jealous stepmother. With his wife Sita, the prince had many adventures and at one point had to be aided by the king of the monkeys. Finally he was able to share the throne with his stepbrother. The poem became familiar to all Indians and Prince Ramayana himself came to be looked on almost as a god, the ideal man and saviour of mankind.

The other great Indian poem was the Mahabharata, which included such a variety of compositions that it was like an encyclopedia of moral teachings. In it, for example, was the Bhagavad Gita, or “Lord’s Song”, a beautiful philosophical poem. The main epic told of a great war, whose climax was a battle lasting eighteen days. All the states and people of India were described as taking part in the battle, which ended in the destruction of almost everyone. Although based on stories of real wars, the poem was full of legendary and fantastic elements.

The Ramayana also combined imaginative tales, legends, myths and history. Both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata had been passed on from generation to generation by professional reciters for centuries. Even after they were written down, many additions and changes were made, since they were not sacred writings like the Veda. As a result, there were old non-Aryan and early Aryan sections side by side with those of later periods. Altogether, a great number of reciters, poets, editors and priests worked on the poems through many centuries. The priests were especially anxious to make the poems as expression of Hinduism.

It was in the centuries following 1000 B. C. that Hinduism emerged as the religion of India. Certain elements of Hinduism existed as far back as the first Indus valley settlements, but Hinduism really developed out of the early Aryans. Their primitive forms of worship had little resemblance to later Hinduism, but as time went on their nature gods became more refined and their beliefs more complicated.

Vishnu, for instance, was only one name of the sun god of the early Aryans. In Hinduism he became one of the major gods and as Vishnu the Preserver he belonged to the trimurti , or “three-formed” god. The other two forms of the trimurti were Brahma the Creator and Shiva the Destroyer.

By 600 B. C., Hinduism was spreading through all Indian life and thought. Much of the growth of Hinduism was due to the influence of the priests, or Brahmins. The priests of the early Aryans had performed the ceremonies and chanted the hymns. By giving up worldly pleasures and devoting themselves to religion, the Brahmins had gained great respect. They were responsible for keeping alive the sacred texts and over the centuries they developed the elaborate ceremonies and the rules of conduct for Hindus. The Brahmins thus became not only priests, but also teachers and lawgivers, setting themselves apart as a superior class.

Social classes were becoming an important part of Indian life. There had already been different classes of people in the early Indus Valley settlements and the Aryans, when they appeared, set themselves up as a ruling class. Under the Aryans, society developed along more rigid lines and people became fixed into different varnas, or classes. At the top were the Brahmins, the learned and priestly class. Then came the warriors and rulers. Traders, farmers and skilled craftsmen formed the next class and lower still were the mass of common labourers. Finally, there were the “untouchables” – such people as the half- wild tribes, the Dravidians of the south and the workers who did the dirtiest jobs, such as sweeping.

Along with the class system, there developed the castes. A caste was a group of families who shared the same dharma, or code of conduct. The dharma, for instance, laid down certain rules for ceremonies and diets and it was important for everyone to carry out his caste’s dharma. When castes started they were not too rigid, but gradually hundreds of castes developed. Each one was closed to all except those born into it and people were expected to marry within their caste. Not everyone in a caste necessarily held the same job, but they were all the same social class.

The Brahmins supported the class and caste system because it helped to keep order in Indian society and was closely related to Hinduism. One of the basic beliefs of Hinduism was the law of karma, which stated that a man’s future life depended on his past behaviour. The Hindus believed that a person passed through many lives. The early ones may even have been as animals, but as long as each living being behaved properly, he kept rising through better lives. Hinduism thus encouraged people to accept their position in a class and caste and not to try to change society. The important thing was for each person to carry out his duty and then he would be rewarded in his next life.

Hinduism did more than discourage people from trying to improve their lot on earth; it urged them to turn away from the material things of this world. Perhaps this was the most important teaching of Hinduism. The spiritual ideal of the Brahmins existed outside the world of matter. Their ideal was an absolutely pure state, beyond nature, reason and experience.

Such teachings were difficult to understand, but the Brahmins were satisfied to have it that way because the mass of Hindus came to accept things as they were. Not everyone, however, was satisfied with the established religion. Some people objected to the elaborate ceremonies and the animal sacrifices. A few men turned to the sacred writings, like the Upanishads or the Bhagavad Gita, which seemed to speak directly to the gods. Others felt that a way to earn a better life in the future was to turn away from their present life and they became monks who punished their bodies.

One man who tried to reform Hinduism was Vardhaman, later called Mahavira, or “Great Hero”, by his followers. Born about 540 B. C., Mahavira became a monk, but after growing dissatisfied with that life, he travelled about preaching. He taught that everyone should behave humanely to everyone else and always obey the rule of ahimsa, or ‘non-injury’ to all forms of life. Since everything – including plants, minerals, air and fire – had a soul, man must take care not to injure them. A man should not walk at night, for instance, for fear of stepping on an unseen worm. Such beliefs required great self-control, but when Mahavira died about 470 B. C., he had thousands of followers, who became known as Jains.

Buddha The “Enlightened One”

It was during this period too, that another man began to question Hinduism. He was Siddhartha Gautama, who was born 560 B. C. He became known as Buddha, the “Enlightened One”, because he was said to have passed through 550 previous births and lives before reaching his final life on earth. According to tradition, his noble father kept the young Siddhartha in a palace surrounded by luxury and amusements, so that he would not know about the sufferings in the world. Siddhartha grew up, married and had a son. When he learned about the outside world, he gave up his nobleman’s life and went off to become a monk.

At first he exposed his body to great pain, but then he realized that a life of hardship was no better than a life of ease. “Better than matted hair and ashes,” Buddha said, referring to the monks, “are truth and discipline.” Buddha began to teach people to take the Middle Path between the extremes of luxury and the monk’s life. The goal was nirvana, freedom from all the desires, pains and delusions of the world. Only when he reached nirvana did a man escape from the cycle of births, deaths and rebirths; to reach his goal, Buddha taught that a person must follow the Eightfold Path of Salvation. Buddha did not offer a religion of gods and ceremonies. His Eightfold Path of Salvation was meant as a guide to right living and right thinking.

When he started to teach, Buddha had only five disciples but after forty-five years he won over thousands of persons to his way of thinking. At the age of eighty, with several of his followers gathered about, Buddha lay down and died. His body was cremated and for a while various followers quarrelled over what should be done with the relics of his body. Finally they were placed in eight stupas, or relic mounds. Many people adopted the yellow robe of the Buddhist monk and spread his teachings.

At first, Buddhism and Jainism were rivals, yet they had much in common. Both came out of traditional Hinduism and accepted certain basic ideas, such as karma and rebirth. Both attacked the caste system and tried to appeal to the mass of people; their writings were even in the common language. Both were religions based on a way of life rather than on a belief in gods. Both considered life in this world as temporary and they rejected its pleasures. Both rejected the sacrifices of animals, too, encouraging respect for animal life.

There was an important difference between Buddhism and Jainism. Jainism accepted almost all of Hinduism and so remained a Hindu sect, winning converts largely in India. Buddhism, however, broke away from Hinduism completely, rejecting the Brahmin priests, the rituals, the gods and the Veda. As a result, Buddhism won most of its converts outside of India.

Whilst Buddhism and Jainism were developing, other forces were at work in India. About 500 B. C., the Persian Empire had made the northwestern region of India one of its provinces. The capital was Taxila, a seat of Hindu learning. Although the Indians paid a large tribute in gold and provided soldiers to fight in Persia’s wars, Persia did not bother with the rest of India. 150 years later, the Persian Empire was taken over by Alexander the Great. Finding himself on the edge of India, Alexander started across the mountains in 327 B. C., fighting off the hill tribes. The next year he crossed the Indus River and approached Taxila. The Rajah realized it was hopeless to resist and welcomed Alexander with gifts of thousands of cattle and the promise of troops.

All the other leaders of the region, except one, soon did the same. The king who defeated Alexander was Poros, a giant of a man. Alexander had boats carried overland to the Hydaspes River, sailed up-stream at night and took Poros and his men by surprise. That day a great battle was fought on the plain along the Hydaspes; the chariots and elephants of Poros could not maneuver against the cavalry and bowmen of Alexander and it ended in total defeat for Poros.

The wounded Poros, when asked how he expected to be treated, told Alexander, “Treat me like a king!” Alexander was so impressed by his bravery that he placed Poros in command of the region. Alexander then moved eastward, capturing territory and founding new settlements, until his troops became restless at being so far from home. Setting up twelve altars at the farthest point he reached, Alexander then took his army down the Indus to the sea. He had been in India less than two years.

No Indian of the time even mentioned Alexander in writing, despite his ambitious hopes of uniting the best of the Greek and Indian cultures. He had brought a number of learned men with him and in time the civilizations of India and the Mediterranean had some influence on each other, but in Alexander’s day there was a gulf between the two worlds. Alexander, it was said, once saw a group of Indian holy men. He sent one of his Greek aids to ask them about their wisdom. The holy men were sitting naked under the hot sun when the Greek delivered Alexander’s request. “No one who wears European clothes could understand our wisdom,” the holy men said. “you must sit here naked on the hot stones to learn.”

Within two years of leaving India, Alexander died. When word of his death reached India, there were mutinies among the troops he had left behind and the Indian states had to struggle for control. One of the Indian leaders was Chandragupta, who as a young man had met Alexander. Chandragupta seized the throne of the kingdom of Magadha and in 323 B. C. founded the dynasty named after his clan, the Maurya. Soon he was ruling much of northern India from his capital at Pataliputra.

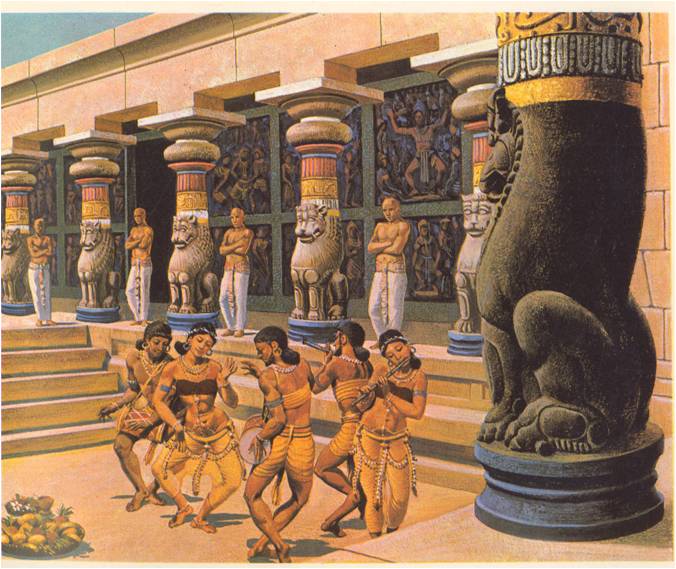

Megasthenes, a Greek serving as an ambassador, described the wonders of Chandragupta’s court. The great wooden palace had pillars encased in flowering vines made of silver and gold. Chandragupta had a bodyguard of armed women. Each year there was a ceremony at which the king had his hair washed in public. For amusements there were chariot races, hunting and dancing girls. At the same time, Chandragupta organized his empire, controlled taxes and irrigation, had a spy system and enforced strict laws. When he died in 298 B.C., he left the first true Indian empire to his son Bindusara.

Little was recorded of Bindusara’s deeds, yet he must have extended and strengthened the Mauryan Empire. The southern tip of India remained isolated and there were always hill tribes and certain sections that stayed independent. When Bindusara’s son Asoka took control in 269 B.C., he ruled most if India. At first Asoka led the life of a great king, hunting and feasting. Then in 261 B. C., he made war against Kalinga, a state to the east. Asoka won, but a great many men were killed or taken prisoner. When Asoka saw what suffering his ambition had caused, he was filled with sorrow and regret.

“All Men Are My Brothers”

Almost at once, Asoka began to change his way of life. He gave up hunting and eating meat and all such pleasures. He also lost his desire to conquer by force and set about to win over men’s hearts. He asked other rulers to follow his new policy and he warned his officials to stop using torture and harsh punishments. He helped the poor and the weak and organized aid for animals as well as for people. Everyone, Asoka said, should be allowed to live in peace, security and joy. Repeating a statement of Buddha’s, Asoka said, “all men are my brothers”.

As part of his new life, Asoka had adopted the Buddhist faith. Hoping to convert others to Buddhism, he sent out missions of Buddhist monks, some of whom went as far as the former empire of Alexander in western Asia and Africa. He sent his own brother to bring Buddhism to the island of Ceylon, off southern India. To clarify the Buddhist beliefs and writings, he called a council in his capital. Buddhism owed a great deal to Asoka, who helped to establish and spread the religion. At the same time, he never forced his people to adopt Buddhism and showed his respect for all religions.

While working to spread Buddhism, Asoka also kept a firm grip on his empire. He was a practical man as well as a religious one and he was wise enough to realize that his peaceful policies were helping to keep order in India. He even had his laws and proclamations inscribed on stones and pillars, throughout the land so that his people would be informed.

Under Asoka, India prospered and his name came to be honoured throughout Asia. When he died in 232 B. C., however, the great empire built up by his family was split between two of Asoka’s grandsons. Then came a series of kings, none of whom was strong enough to unify the land. To the people of India, it made little difference. Their religion taught them that the struggles and victories of the world did not really matter and they continued their age-old ways.