Old Europe crumbles as barbarian waves batter civilizations. Ironically, the victory on the Mauriac Plain sealed the fate both of victor and vanquished. After his death in 453, Attila’s empire broke up not only as a result of the feuds among his heirs, but also because of a successful rebellion among his German subjects. For the victorious Roman general, Actius, the outcome of the battle was still more directly catastrophic. He fell victim to a palace conspiracy of enemies who feared his immense prestige. The Emperor Valentinian III, is said to have boasted of the disposal of this powerful and popular rival to a favourite courtesan. Her laconic reply was: “‘You have cut off your right hand with your left.”

With the sack of Rome in 455 by the armies of Gaiseric the Vandal, the weakness of the Western Empire was fully revealed. Thereafter, the influence of barbarians in the imperial court, which had been considerable, became supreme. From his victory over Vandal armies in 456 to his death in 472, the Suevian general Ricimer was arbiter of the fortunes of the West. Beyond the Alps, only the territories of Syagrius in northern France remained under Roman rule and these constituted, because of their isolation, a virtually independent kingdom, soon to be destroyed by Clovis. During the brief reign of Majorian (457 – 61), the best traditions of the Empire were revived by that competent and conscientious ruler, but his growing prestige was a threat to Ricimer, who had him deposed and murdered. For another fifteen years, the fiction of a Western Emperor was maintained, but in 476, the auspiciously named but pitiable figure of Romulus Augustulus was wiped out by the soldiers of Odoacer another successful German soldier, who like Ricimer, succeeded in wielding real power in the West.

In the East, thanks to the determined efforts of the emperors, the influence of barbarians in the armed forces and the capital itself was held at bay. Despite the abortive expedition sent by Leo I, against the Vandals in 468, the integrity of the eastern half of the Empire, was largely maintained. Leo’s son-in-law and successor, Zeno, was at first obliged to accept the coup d’état of Odoacer; later, he cleverly diverted the Ostrogothic tribes in the Balkans, by commissioning them to put an end to Odoacer’s regime in Italy.

New Powers: the Visigoths in Spain

It was the Visigothic army, that at the battle of Adrianople in 378, defeated the Emperor Valens; it was the Visigoths under Alaric who sacked Rome itself in 410. Yet, ironically, three centuries later, it was the Visigoths who were virtually extinguished in their attempt to defend their Romanized Christian traditions against the invasions of a new wave of barbarians.

By 415, Alaric’s successors had led the Visigoths through Gaul to Spain. There, in a series of campaigns fought ostensibly on behalf of the imperial power at Rome, they drove out the earlier Germanic settlers and returned most of the Iberian peninsula to imperial rule. As a reward for their labours and lest they should become too powerful, they were settled in the large territories of southwest France, later to be the semi-independent duchy of Aquitaine.

This Visigothic kingdom, free from all allegiance to the Roman Emperor, expanded dramatically. Under its great King Euric (c. 420 – 486), it extended from the Loire to Gibraltar. It comprised the whole of southern France west of the Rhone and all of Spain, save the tiny states of the Basques and the Suevic kingdom to the northwest. It was this mighty power, with its capital at Toulouse, that was overthrown by Clovis and his Frankish army at the Battle of Vouille in 507. As a result, the Visigoths were, for the rest of their history, confined to Spain, except for a small stretch of territory on the southwest Mediterranean coastline of Gaul. Yet, reluctant to recognize the completeness of their defeat at the hands of the Franks, the Visigoths did not move their capital from Toulouse to Spain until as late as the 540s. The saviour of the Visigothic cause in France had been Theodoric, the Ostrogothic king of Italy, who viewed with disquiet, the rapid rise to power of the Franks. In addition, Theodoric also acted for a time, as regent of the French Visigothic kingdom and did much to lay the foundations of its future.

A vital part of the Visigoths’ barbaric past, which was in part the cause of their ultimate downfall, was the principle of the elective monarchy. The principle indeed underlay the kingship of all the European post-barbarian kingdoms; but the internal division and weakness caused by elective monarchy, were particularly serious in the exposed peninsular kingdom. The success of Justinian’s Roman armies in Spain, was facilitated by the divisive rivalry for the Visigothic throne, during the middle of the sixth century. The natural preference of the Romano-Iberian population, for the religious orthodoxy of the Byzantine Empire, as opposed to the Arian Christianity of their conquerors, strengthened the Byzantine position, as did the conversion of the Suevi in the north-west to Catholicism. Yet, despite this religious antipathy among the subject population, the great Visigothic king Leovigild, who finally established the capital at Toledo, was able to recover much of the territory lost to Rome. Further more, Leovigild lessened the effects of the religious conflict by passing legislation in favour of mixed Arian-Catholic marriages. His successor, Reccared, took the process to its logical conclusion: he presided over the third council of Toledo in 589, which by a majority decision, proclaimed orthodox Catholicism, the state religion. Yet, the effects of the Arian period continued to be felt.

The king still possessed a decisive voice in religious affairs, a feature of Spanish life that remained prominent. Indeed, in the sixteenth century the notorious Spanish Inquisition was, in effect, an agent of royal policy. Under the Visigoths, the regular councils of Toledo, formed the great council of an almost theocratic state.

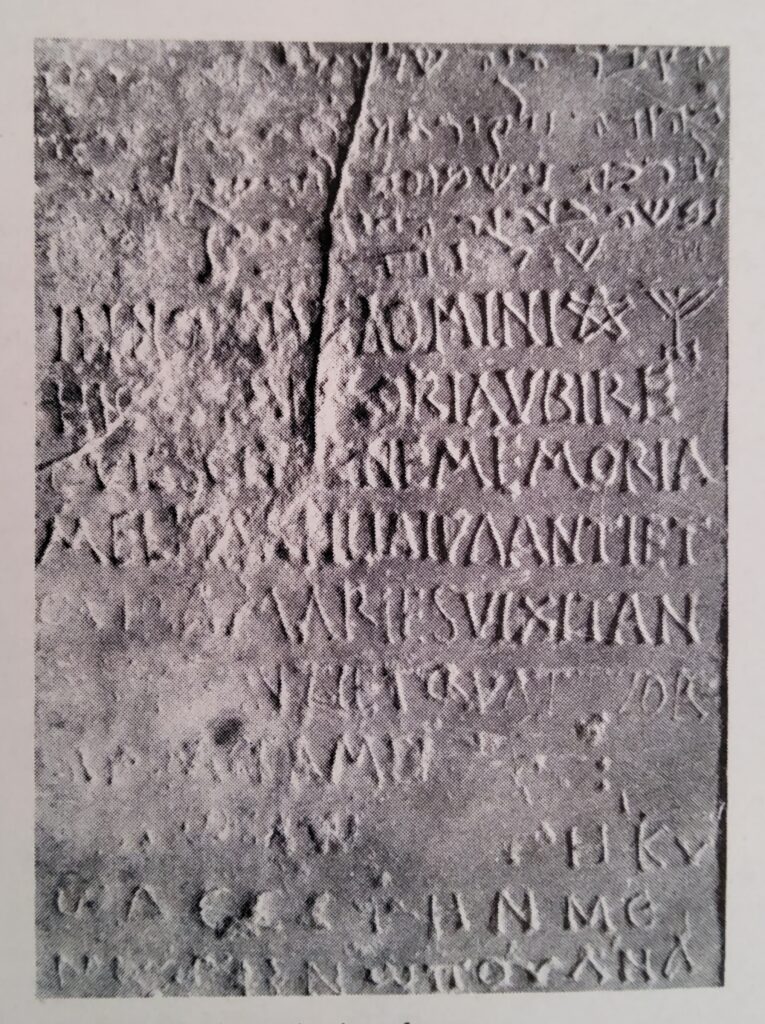

It was one of the great achicvements of the Visigoths, that after their acceptance of Catholicism, they succeeded in welding into one people, the diverse races of the Iberian Penninsula. A major reason for their success, was the immensely significant legal code promulgated by King Recceswinth, in the 650s. The code, written in Latin, was not only the first major legal code to be issued by one of the successor barbarian kingdoms, but it also, most significantly, unified into a single legal system, the Roman and Visigothic laws, of the two populations.

The Ostrogoths in Italy

The Italy St. Benedict knew, was that of Theodoric the Ostrogoth, the barbarian ruler who most truly and splendidly, continued the traditions of the ancient Rome, that he had displaced. Theodoric’s exact status within the political environment of the late antique world is not absolutely clear. In a letter written to the Byzantine Emperor Anastasius, he acknowledged the Emperor’s seniority and admitted that his own court could only attempt to imitate the magnificence of Constantinople. Doubtless, this was true, but it is clear from the tone of Theodoric’s letter and from an evaluation of his whole policy, that the Ostrogoth ruler regarded himself as a free agent throughout Italy and in his dealings with the barbarian kingdoms to the north.

Theodoric had led the Ostrogoths into Italy in the late 480s, at the invitation of the Emperor Zeno himself. Zeno’s aim was twofold: to free the Balkans of the depradations of the Gothic hordes and to re-establish in Italy, a power that at least recognized the suzerainty of the empire. Since the year 476, Italy had been under the rule of Odoacer. German troops under his command in the north, had revolted against the feeble authority of the last of the Western Emperors and demanded land in payment for their services. When their demands were refused, the youthful Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was deposed. Messengers were sent to Constantinople, demanding that Odoacer be recognized as the imperial vicar in Italy. When Odoacer, however, lent his support to a pope who was unacceptable to the Emperor, and then to a rival for the imperial throne itself, his days were numbered. Within five years of Theodoric’s arrival in Italy, the troops of Odoacer were defeated. Odoacer himself, after a three-year resistance in the marsh-girt city ol Ravenna, surrendered only to be treacherously murdered.

Theodoric had secured Italy in the name of the Emperor, but thereafter, he was to rule with the assistance of the powerful landowning bureaucracy and through the coercive power of his Ostrogothic soldiery, whom he rewarded handsomely with land — as King of Italy and Dalmatia.

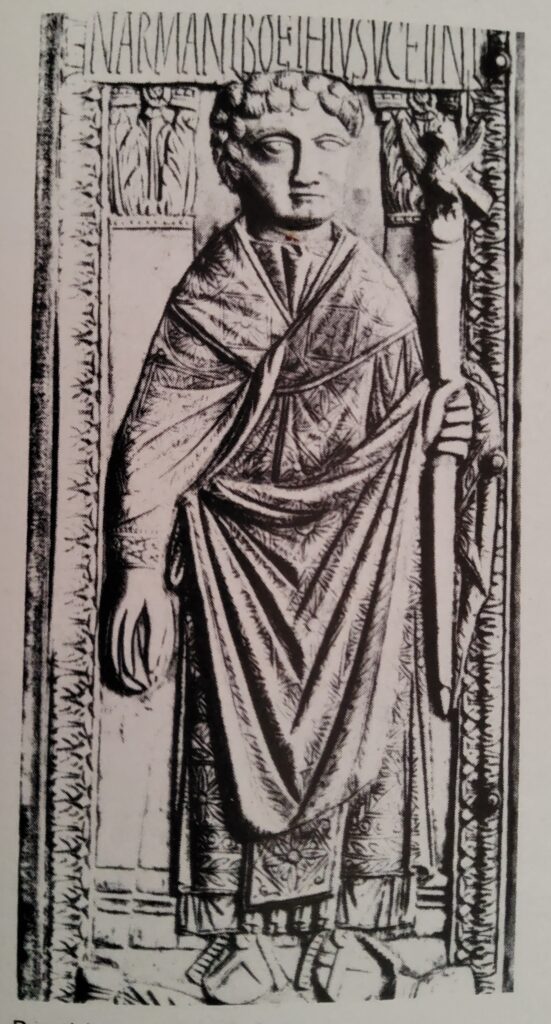

During the reign of Theodoric, Italy enjoyed a late Indian summer of peace and prosperity. Even a Byzantine historian observed that Theodoric had been a fair and just ruler to all his subjects. Nevertheless, some members of the old patrician class, Orthodox in religion and opposed to the Arian Ostrogoths, nostalgic for the distant past of Roman imperial grandeur and unwilling to lose touch with the representative of that tradition, attempted to open negotiations with the Byzantine court without Theodoric’s knowledge. Regarding this as treason, Theodoric ordered the execution of a number of senators, among them his one-time councillor and friend, Boethius.

Boethius’ “On the Consolation of Philosophy”

Boethius, the man described by Gibbon as the “last of the Romans whom Cato or Cicero could have acknowledged as their countryman,” was a man whose philosophy, was to be of seminal importance throughout the Middle Ages. He wrote in the strong tradition of ancient classical and pagan learning. His most famous work, On the Consolation of Philosophy, was popular in Europe, upto the Renaissance. Written while he was in prison awaiting his execution, it is in the form of a dialogue between Boethius and Philosophy, personified as a decorous and beautiful woman. Boethius, an influential adviser at Theodoric’s court, had been consul in the year 510. He lived to see his sons become consuls in their turn. He believed that the false charges of treason, which accused him of plotting with the Emperor Justin for the overthrow of Theodoric, for the restoration of the ancient liberties of the senate, had been brought by powerful enemies, whom he had offended by his defense of the interests of the poor citizens in his role as consul. Boethius, later to be canonized as a saint, was quite mistakenly regarded as a champion of trinitarian orthodoxy, against the Arian heresy, favoured by the Ostrogothic court. Indeed, it may well have been an imperial edict of Justin against the appointment of pagans, heretics, or Jews, to official posts that first awoke the suspicions and anger of the aging Theodoric.

The religious division between the Orthodox Emperors and their Arian Ostrogothic agents in Italy, exacerbated the increasingly uneasy relations between the two. On his death, Theodoric was succeeded by his daughter, Amalsuntha, whose admiration for and loyalty to, imperial Rome, was well known. In time, however, her loyalty to the Emperor alienated her from the Ostrogothic nobility; in 535 she was overthrown and murdered. This provided the pretext for which the Byzantines had been waiting: the first campaigns of Justinian’s generals heralded the end of Ostrogothic rule in Italy.

The reign of Theodoric was a glorious period in the history of early medieval Italy. At his capital of Ravenna, Theodoric built a palace of considcrable splendour, closely modelled in style, on Diocletian’s palace at Spalato (Split).

Monuments of the Ostrogothic period

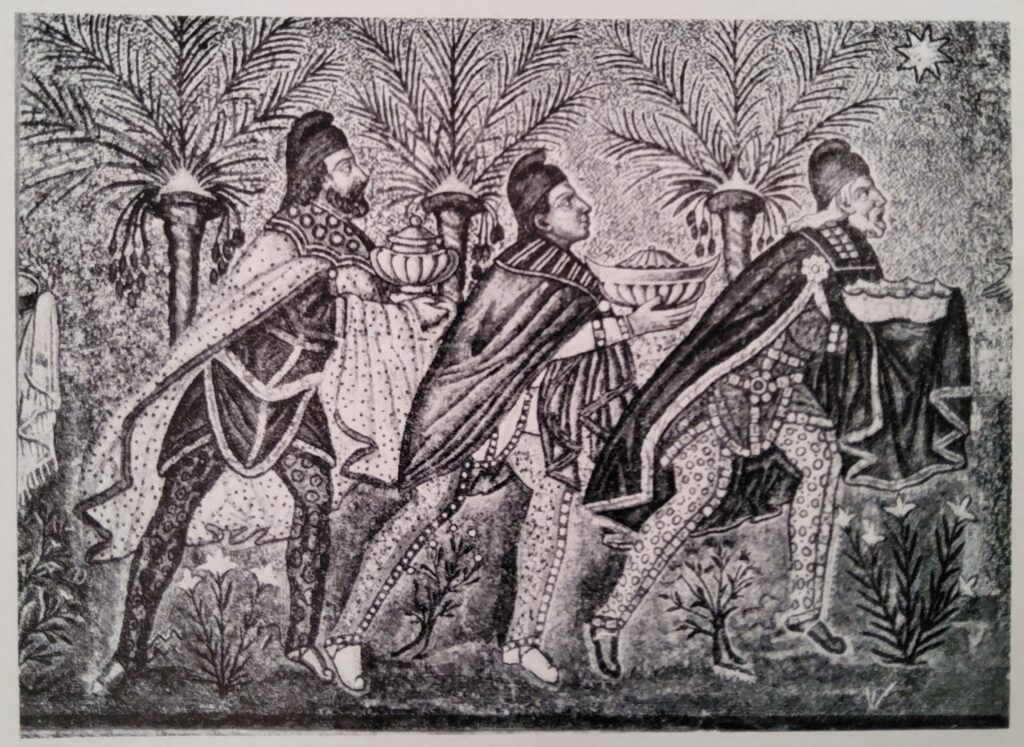

Among the great monuments ol the Ostrogothic period that have survived to the present, are the church of San Apollinare Nuovo and the superb mausoleum, that Theodoric had built for himself. Unusual for its period, the mausoleum was built of stone rather than brick and is roofed with a single circular block, weighing over 450 tonnes. The placing of the roof represents a major engineering achievement in the tradition of ancient Rome. The work of Theodoric’s artists, which glorified both the religious doctrines of Arian Christianity and the greatness of the Ostrogothic state, was replaced at Justinian’s order with a mosaic scheme, based on Orthodox Christianity. In such troubled times, many of the traditions of Roman culture were kept alive in the cells of Benedictine monasteries.