Justinian Corpus, the Juris Civilis, is the ancestor of all European legal systems. The sixth century – in the West, a period in which the seeds of a new type of monastic and Church-orinented culture and a fragmented political system were being planted. This century, was for the Eastern Roman Empire and its Persian rival, an age of great splendour. Despite the closing of Plato’s academy at Athens by Justinian in 529, the tradition of lay classical learning was never broken. Moreover, the Arab civilization emerging in Egypt, Syria and Persia continued and even developed that tradition. The case with which the Arabs overthrew Persia and conquered great tracts of territory from Rome, was largely the result of the fierce religous ardour of their new Moslem faith; but there were also weaknesses within these great empires.

The Age of Justinian

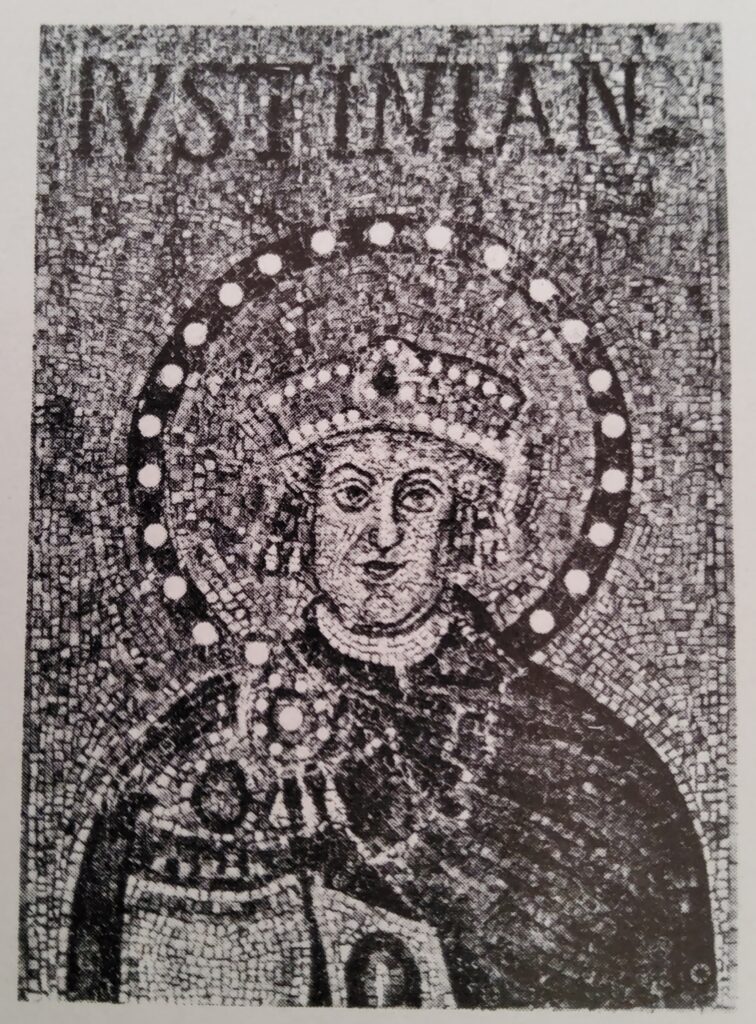

The Eastern Roman Empire was not unscathed by the turmoil of barbarian invasions, but whereas the Western Empire ceased to exist as a political entity, the East recovered. After a period during which the barbarians in the service of the imperial army had dictated events in Constantinople, there followed the reign of the Emperor Zeno. Although orthodox himself, he was willing to attempt a compromise with the powerful monophysite heresy, a heresy that denied the dual nature of Christ as man and God and claimed that he had only one nature — the divine. Zeno’s successor, Anastasius I, restored the failing finances of the Empire and laid the foundations of the greatness of the sixth century, but his monophysite tendencies were marked. His successor, the aging but well-entrenched chief of the imperial guard, Justin, permitted no half measures; his persecution of the monophysites was total; he launched the edict against pagans and heretics that so angered Theodoric, an Arian. If he was sound on religion, Justin was also very much a soldier and aware of his own limitations. He was virtually illiterate and he increasingly entrusted the government to his nephew, Justinian, who succeeded him as Emperor in 527.

It was not at all clear to the people at the time, that the might of Rome was finally a thing of the past. None of the intruding barbarian kingdoms had produced valid new systems of administration and both Theodoric and the Frankish ruler Clovis had accepted the imperial insignia of office. When Justinian came to the throne, the Ostrogoths in Italy were facing difficulties after the death of Theodoric, even the Franks were showing signs of chronic internal divisions. Throughout the Mediterranean world, in fact, the upstart regimes seemed ripe for conquest.

Only with the wisdom of hindsight, can we see that the universal Roman Empire of antiquity had been irreversibly split and that the populations of Italy, Africa and Spain neither needed nor wanted the government of a distant capital with its dying ideals. Nevertheless, by the end of his reign, Justinian, thanks to the talents of brilliant generals like Belisarius and Narses, had not only checked the Persian advance, but also made the Mediterranean, once again a Roman lake.

Vandal empires crumble

First to go was the Vandal kingdom of Africa, Sardinia and Corsica; shortly after, Sicily was taken from the Ostrogoths. The conquest of Italy itself was to be delayed, largely by intrigues at the court against the generals in the field. Finally, in the middle of the sixth century, the Roman armies succeeded in recovering southern Spain from the Visigoths. Within its own terms, Justinian’s policy, no matter how heavy the drain on the Empire’s resources, was successful. However, it must be realized that within a century of Justinian’s death, the ill-defended Danubian frontier, his major strategic blind spot, had been breached by Slav and Avar invaders. While they were conquering a large part of the west Balkans, most of Justinian’s Mediterranean territories were being lost. The most completed reversals, of course, were due to the astonishing advance of Islam.

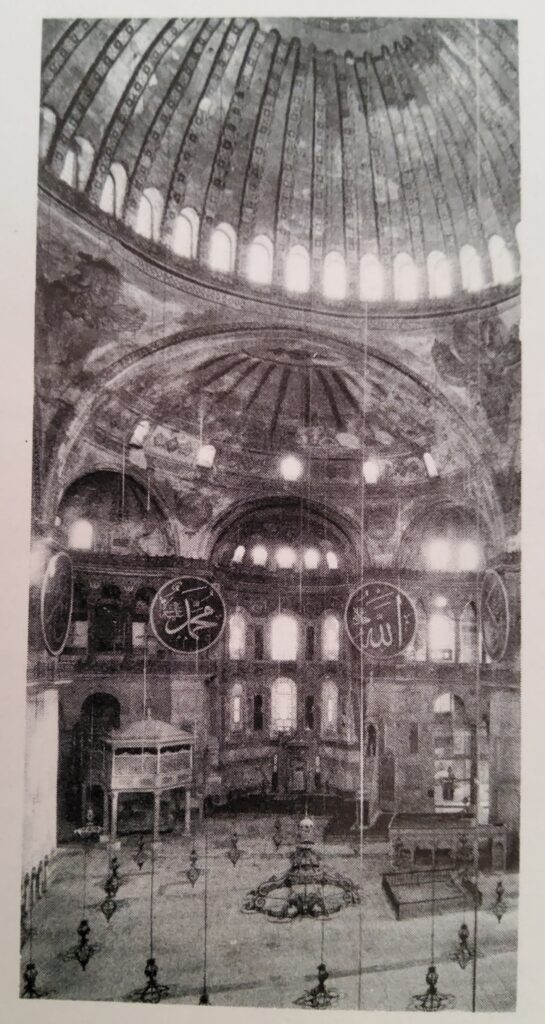

Besides making notable territorial gains, Justinian, drawing again on the wealth of the imperial treasury and imposing increasingly heavy taxes on the old and newly conquered lands, put through a vast program of public works that glorified Rome, Orthodox religion and himself. Chief among these were the church of San Vitale at Ravenna and the great cathedral of Hagia Sophia at Constantinople, one of the most remarkable achievements in the whole history of architecture. The jubilant Emperor is reported to have ridden his horse up the main altar of the basilica and cried out: “O Solomon, I have outdone thee.”

Dissension and weakness

It is in the nature of empires, to decay. Yet whatever the strictures of later historians, there is no real doubt that for half a century, thanks to the ambitions and qualities of Justinian, the Empire in the East enjoyed one of the most brilliant epochs in the history of empires, but the cracks in the structure, were never far below the surface and they found expression in religious differences. The Emperor as head of both Church and State had to ensure both – religious uniformity and the loyalty of heretical territories – Justinian’s attempts to strike an acceptable religious compromise led him eventually into heresy himself. Heresy was adopted in frontier religions such as Syria and Egypt as a mark of their opposition to the central government; in its struggle for independence against Constantinople, the patriarchate of Alexandria adopted monophysitism and the divisions rent, even the capital itself.

Opposed to the Orthodox Emperor was the party of Justinian’s wife, the beautiful Theodora, who supported the monophysite cause. The factional politics of the late Roman imperial court have given us the phrase “Byzantine politics” as a synonym for intrigue and corruption. Procopius, whose official history is our best source for the period, also wrote the scandalous Secret History. In it, himself a representative of the old aristocracy, he attacks the upstart Emperor and his wife, whom he slanders for her humble origins in the world of the actors employed by the circus. Yet Theodora was a woman of courage and political acumen. In a regime where the popular voice was excluded from constitutional expression, the rival sporting factions of the Blues and the Greens of the Hippodrome, focused ostensibly upon the chariot races, acquired some of the characteristics of politcal parties. The Blues were the party of the Emperor and Orthodox in religion; the Greens were the party of the Empress and were monophysites. The two parties were generally rivals, but they united in the famous Nika riots in 532. Justinian would have fled before the fury of the mob, but Theodora and the generals held firm and order was restored.

Corpus Juris Civilis – Justinian corpus

For subsequent generations – this intense, confident and vital period, presents a barely credible amalgamation of the most diverse elements. There can be no doubts about its achievements: its greatest monument, the Corpus Juris Civilis, a codification of all Roman law, was to exert an immense influence on the West and has remained the basis of all systems of Roman law in Europe today.

After Justinian’s death, the Empire’s external enemies made several inroads. The slow but sure progress against these threats by the emperor-soldier Maurice was brought to an end by the usurper Phocas, in 602. His overthrow of Maurice served the Persian emperor as a pretext for several highly successful campaigns of conquest, supposedly to avenge his former protector. The Avar advance gained a fresh impetus. In 610, Phocas was replaced by Heraclius, but the counter attack could not be launched for another decade. During this period, the Persians took Jerusalem, capturing the most sacred relic of Christendom, the True Cross.

The end of an Epoch

Heraclius began a triumphant but arduous campaign of reconquest which ended in 627, with the capitulation of Persia, Rome’s ancient enemy. During the war, the city of Constantinople itself had withstood siege, by both the Avar and Persian forces, but the very year in which Heraclius set out upon his epic campaign, 622, was also the year of the Hegira. Islam thus arose at a time when both Emperor and Empire were exhausted by the depradations and exertions of the previous generation; the hard-won provinces—with them the great Greco-Roman cultural centres of Caesarea, Antioch and Alexandria — were soon lost to the lightning conquest of Islam. The importance of this conquest in shaping the brilliant culture of the Arab World can hardly be overrated.

The Byzantine Era begins

It is usually from the reign of Heraclius, that historians date the beginning of the Byzantine Era, as distinct from the age in which the Eastern Empire is regarded as merely the continuation of Rome. In social affairs the change is marked by the restructuring of the provinces so that the civil and military authorities, separate since the time of Diocletian, were merged under the military authority. At the same time, something similar to the later European system of feudal land tenure was introduced; each province supported a body of troops and the soldiers received grants of land on condition of military service. Greek, rather than Latin, became the official language of the Empire; Egypt, Syria, Spain and North Africa were lost and the possessions of the “Roman” Empire in Italy itself, was greatly reduced. After the time of Heraclius, in fact, the Eastern Empire took on its medieval aspect.

The last glories of the Sassanids

In the fifth century the Persian Sassanid rulers. the weak and ineffective successors of Shapur, were forced to pay tribute to the northern barbarian kingdom of the Hephtalites. To this external enemy was added a subversive religious doctrine, preached by Mazdak, who derived many of his ideas from the teachings of Mani, which also had revolutionary social implications of common ownership of property and of women. The doctrine, which struck at the very roots of the hierarchical and aristocratic system of society, was nevertheless taken up by King Kavadh I, possibly as a welcome weapon against the overpowerful nobility and as a counterbalance to the influence, of the Magi, the Zoroastrian hierarchy at court.

In fact, Kavadh laid the foundations for a revival of the Persian power by combating the anti-monarchist powers within the state, reforming the conditions of peasant life, and restructuring the administration for more effective exercise of royal power. His son, Chosroes 1 (531 – 79), brilliantly extended the achievements of his father’s reign and led the newly confident empire in triumphant war against its enemies: the Hephtalite kingdom was crushed. The northern frontiers were secured against the Huns, while to the south, he even brought Yemen under Persian rule. Against Rome, Chosroes was able not only to invade the Syrian provinces of the Roman Empire, but even to sack the mighty city of Antioch. Pretexts for the dispute between these ancient enemies were never lacking.

The Christian kingdom of Armenia was a constant source of irritation to the Persian emperors and both empires maintained client Arab princes in the buffer zone on their Syrian frontier. The internal disputes of these, could always be seized upon at will, as a casus belli by either of the great powers. Nor was the confrontation fundamentally between the simple opposites of Christian and infidel; monophysitism was strong within the Armenian church and the Arab tribes of Syria, so that the crucial matter of religious unity, was inevitably intertwined with the vexing problem of political allegiance.

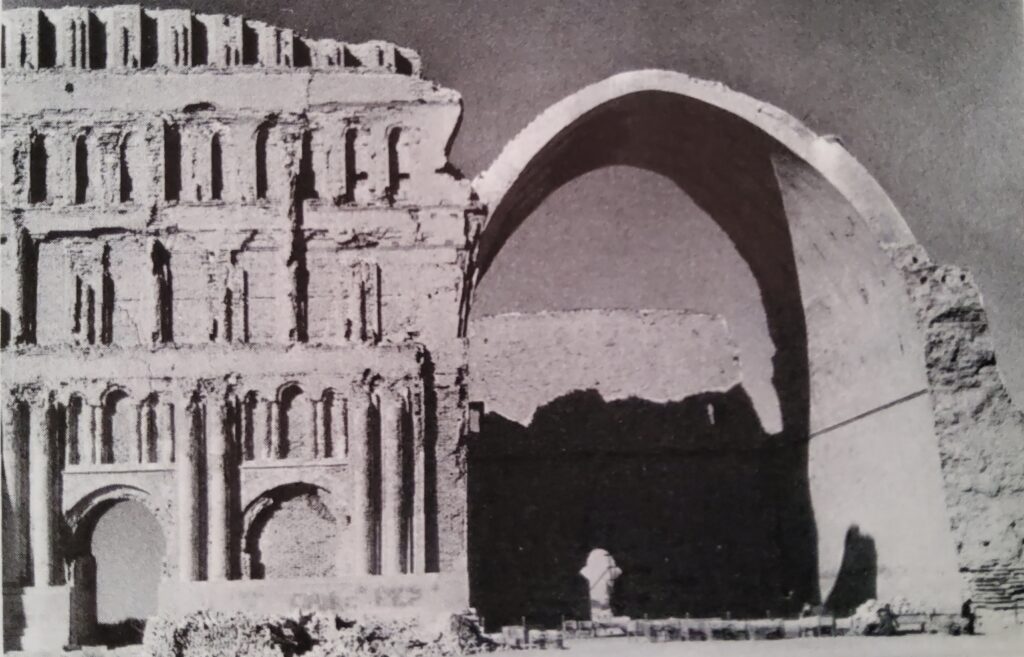

After the glorious reign of Chosroes I, symbolized by the rich and splendid monuments and palaces of his capital at Ctesiphon, whose ruins are still to be seen today, there followed a period ofcivildisturbance and rebellion. It was not until the accession of his grandson, Chosroes 11, supported by the Byzantine Emperor Maurice, that the greatness of the Persian Empire seemed to have returned. Yet, exhausted by the ambitions of Chosroes I, crushed by the defeats inflicted by Heraclius and weakened by renewed civil war and internal dissension, the once mighty Persian Empire fell an easy prey to the armies of Islam, which captured the fabled wealth of Ctesiphon in the year 637.