Alfred “The Great”, alone amongst the English kings, has been awarded this title. Earlier invaders of the British Isles had been assimilated, but the thin veneer of English civilzation in the Dark Ages could not withstand the impact of Danish attacks at the end of the eighth century. The fragmented English kingdoms could not seem to unite against this new terror. Then a saviour appeared — in the guise of the young prince of Wessex, Alfred. In the first few years after he came to the throne, Alfred fought many battles against the Danes — and lost most of them. Then the tide turned; in 886, Alfred took London. He had won a capital and he had also created a nation. More than just a soldier, Alfred was a scholar, determined to foster learning among his people. He translated classical works into the vernacular and issued a new legal code based on the Golden Rule. For this combination of talents, Alfred — alone among English kings — has been awarded the title “The Great.”

When King Alfred of Wessex captured London in 886, he did more than strike a heavy blow at the Danish invaders. In effect, he became the first King of England and established a new idea of nationhood. His action gave heart to Englishmen all over the land, made them feel that the Danes after all could be defeated and kindled in them the sentiment of being English, of being members of a nation. Viewing Alfred as their sole overlord, they broke through the lesser loyalties to region and local leader. When Alfred died, he was King of all Englishmen free to give him their allegiance.

In the autumn of 865, a great host of Danes appeared in East Anglia, with many who claimed to be “god-descended” nobles amongst its ranks. Its leaders were Ivar the Boneless and Halfdan, sons of the great Viking Ragnar Lothbrok. Each autumn the host moved its headquarters; it seized a strong position, fortified it, then ravaged the countryside till the people there bought peace.

The Danes spent a year collecting the horses of East Anglia and forcing the folk to buy peace; then in 866 they moved as a mounted force on York, which they took on All Souls’ Day and held it unchallenged, for four months. Northumbria was at this time embroiled in civil war and it was some time before the rival kings would cooperate. But on March 21, 867, they took the Danes by surprise and broke into York. Quickly driven out again, the two kings, with eight ealdormen, were killed. The Northumbrians bought peace and the Danes wintered in Mercia, at Nottingham.

Inevitably, the Mercian king made haste to find allies. He was married to a Wessex princess and thus able to call on her kinsmen. He was fortunate; aid came from the King of Wessex, Aethelred, who with his youngest brother came at the head of an army. The Danes avoided battle and the Mercians were able to buy peace.

King Aethelred’s young brother, Alfred, was twenty years old in 867. That same year he married Ealhswith, the daughter of a Mercian ealdorman. At the wedding feast he was stricken with illness and while he recovered from the attack, the same illness was to attack him intermittently for the rest of his life. (It was probably epilepsy, though this has never been verified.)

He rarely enjoyed peace of any kind; he was only married two years when a Danish army invaded his brother’s kingdom and made camp at Reading. Aethelred and Alfred summoned their forces and marched on the camp, but their first attack was beaten back.

The host moved on to the great ridge of chalk (then called Ashdown) that runs east to west across Berkshire. The two brothers reformed their forces and followed. The Danes offered battle high up on the ridge in two divisions, one under their kings, the other under the earls. The English army was also ranged in two sections — Aethelred opposing the Danish kings; Alfred, the earls. The Danes fled back to Reading.

A fortnight after this initial success the two brothers, attacking from the marshy meadows of the Loddon, were beaten off by the Danes who fought on firm land. Two months later at Meratun (perhaps Marten, near Marlborough), another hard-fought battle ended with the Danes recovering their ground. Then in mid-April, Aethelred died and Alfred was recognized as his successor without opposition.

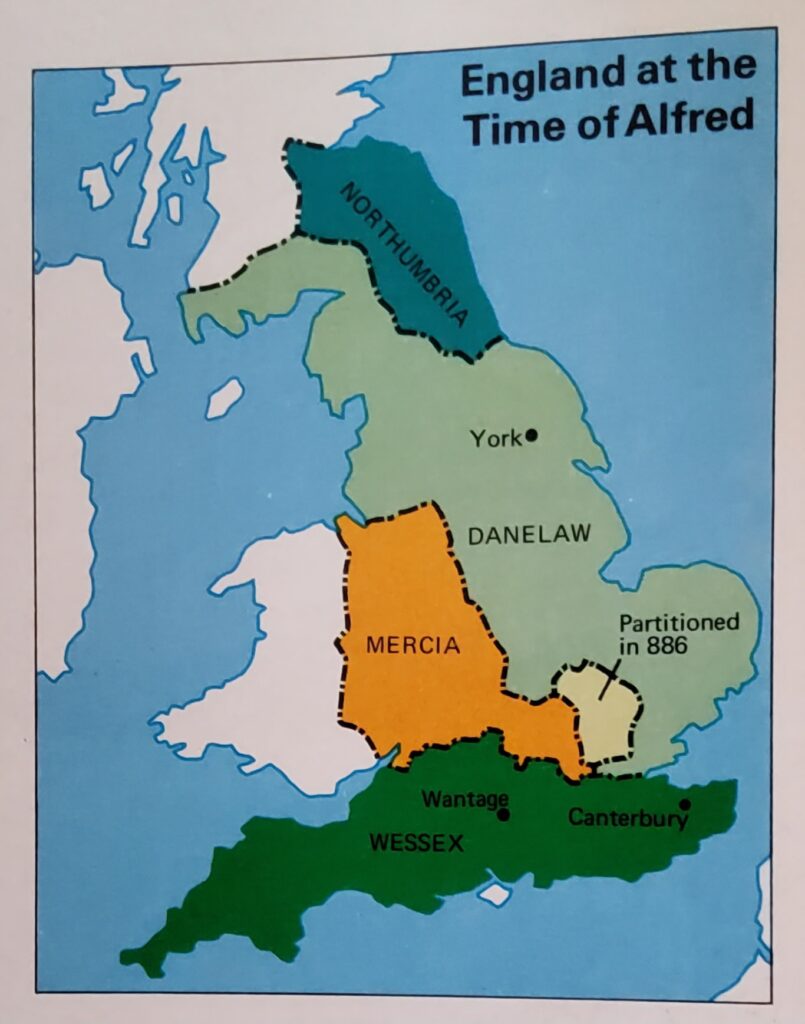

His start as a king was unlucky. While he was at his brother’s funeral at Wimborne, a Wessex force was scattered at Reading; then, a month later, he himself was defeated at Wilton. After a year’s exhausting war, he had to buy peace. Ivar the Boneless seems to have disappeared from history at this point and Halfdan was left to command the Danes. In autumn 873 he led his men from Wessex — which had now had four years of peace — to winter in London. A revolt of the Northumbrian English seems to have drawn them north in 872-73. However, they wintered at Torksey in Lindsey, then moved to Repton in the heart of Mercia. Burhred, the Mercian king, was defeated; he left England for Rome, leaving his kingdom at the Danes’ mercy. They put a puppet king in Burhred’s place and then divided it into two sections which never again united. Halfdan took one group of Danes north to the Tyne and for a year raided the Britons and Picts of Strathclyde. England, long devastated, was losing its value for loot or exactions and the Danes began to consider permanent settlement. In 876 Halfdan carried out the first of three great partitions which gave over more than a third of eastern England to the Danes; in general, the occupied area was that now covered by the county of York — not till the tenth century, was there any large Danish immigration north of the Tees or west of the Pennines. Halfdan left England at this time and was killed in 877, fighting in north Ireland.

Meanwhile, the second section of Danes, under three kings, had gone to Cambridge. They were considering a fresh attack on Wessex. An English force in the fens was keeping watch; but in autumn 875, the Danes slipped away on a dark night and spread across the country. The area around Wareham was laid waste. Alfred had a smaller body of Danes to meet this time; though he was again obliged to buy peace, he was given hostages. The Dances swore to leave Wessex “on their holy armlet,” a more solemn oath than they had so far deigned to swear to Englishmen. They had been a year at Wareham, when despite their oath, they moved off on a night march to Exeter. A storm off Swanage broke a reinforcing fleet and in summer, they departed for Gloucester, the centre of rich lands in Mercia. By the year’s end, they had cut Mercia in two; one half was held by a puppet-king, the other divided among the army. The area they took included the medieval shires of Nottingham, Derby and Leicester.

Settiements however, was a long way off — not all the Danish soldiers wanted to become farmers. Early in 878, a group moved south to Chippenham in Wessex, where Alfred often went to hunt. They were led by Guthrum, apparently the last survivor of the three Danish kings. Never before had a Danish army moved during winter and their unexpected irruption forced much of Wessex to submit. Some West Saxons even went overseas, while Alfred retreated into the rough regions west of Selwood. East Mercia and Northumbria were lost and East Anglia, helpless. Luckily a Danish fleet from Dyfed foundered off Dorset and Wessexmen won a minor victory at Countisbury Hill. At Easter, his kingdom was overrun and his army decimated. Alfred withdrew to the Isle of Athelney in the Somerset marshes, a thick alder forest with sparse clearings. The Danes held everything now — except the king’s person. It seemed that soon Wessex too, would be partitioned.

It was a critical time and one that has passed into the legends of English history. It is only too believable that Alfred would have had the wit and the courage to visit the Danish camp as a bard and listen to his enemy discussing the plans for attack. Alfred could have done it had he loved music all his life and in that age, it would have been essential for such a man to be able to play and sing himself. The famous episode in the peasant’s hut probably took place at this period too, assuming that it actually happened. He was probably on the way back to his forest retreat after spying on his foes, when tired and hungry, he sought shelter and a morsel to eat at a humble dwelling. The good housewife, believing him to be an unknown wayfarer, set the bread to bake and promised him food and shelter. She asked him to watch the bread and see that it did not burn. Alfred, worn out with his exertions and preoccupied with the cares of his lost kingdom, forgot all about the bread. He sat there quietly while the poor woman, her batch of bread ruined, unknowingly scolded her king as a useless, idle fellow.

Alfred’s courage and tactical skill, saved the situation. He went on tackling Danish raiding-parties and after seven weeks grew strong enough to think about the army itself. Leading the men of Somerset, Wiltshire and Hampshire (west of Southampton Water), he met the enemy at Edington and won a decisive victory.

For a fortnight the Danes resisted in Chippenham, then agreed to have their king baptized and leave Wessex. In the summer of 878, their still powerful host retired to Cirencester in Mercia for a year, then went back to make a final partition of East Anglia. Wessex alone of the English kingdoms survived the Danish onslaught intact. In what had been Mercia, Northumbria and East Anglia, three large hosts of Danes had settled on the land. The next seventy years were to be taken up with the struggle to reimpose English rule (in the name of the West Saxons) on the lost areas; but nothing could wipe out the social effects of the settlements, all over the larger part of England, that came to be called the Danelaw.

In the autumn of 878, however, a new Danish host entered the Thames and wintered at Gulham, but Alfred had changed the whole situation. In November, 879, the Danes departed for the Low Countries. Guthrum no doubt, had no wish to challenge Alfred again. The English were watchful and when, in late 884, a part of the new host landed in Kent, Alfred drove them away. The Danes tried two more raids, aided by the Danes of East Anglia. Alfred decided to teach the latter a lesson by sending a fleet into their waters. He managed to capture sixteen Viking ships off the mouth of the Stour, but before he could depart, his fleet was beaten by a large Danish force.

Alfred captures London

It was at this time that Alfred took London and while the details are scarce, it was an event of the first importance; it was after this victory that he assumed the supreme title. He showed that he meant to respect the traditions of each area coming under his overlordship; since London had been Mercian for some 150 years, he handed it over to Aethelred, ruler of English Mercia, who was henceforth his faithful ally and henchman. The settlement of the 886 war is preserved in a treaty between Alfred and all the counselors of the English people and all the foik of East Anglia under Guthrum, the Danish king.

The treaty, as between two equal powers, laid down boundary lines. Alfred claimed no supremacy over Guthrum’s area, but doubtless felt that the treaty gave him the chance of securing the interests of the English there. His power reached as far as the Humber River in the north.

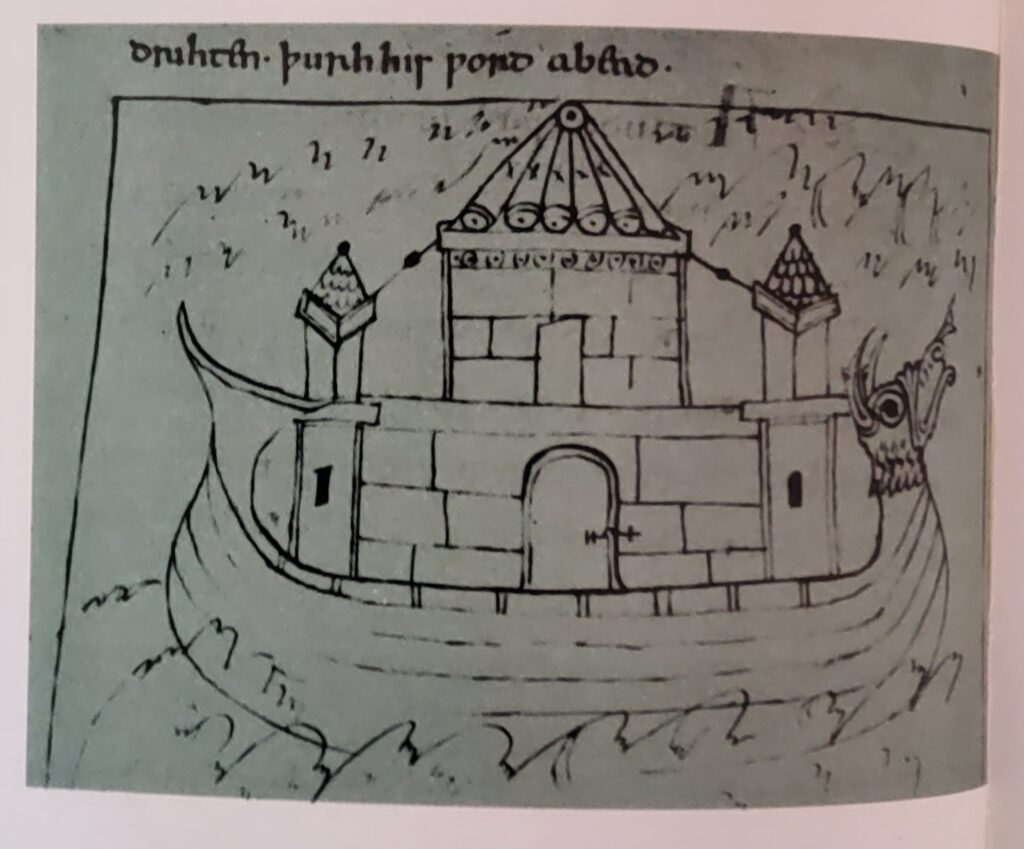

Peace was not to be had for long. In 892 a great host, defeated in the Low Countries, assembled at Boulogne to invade England. The Danes of East Anglia aided the newcomers and a protracted war resulted in that. Alfred realized that he must build a strong navy as well as reconstruct the land-defenses. The shire-levies were no longer adequate, so by allowing half the peasants to stay at home while the other half campaigned, he was able to assemble a good army which could be held together much longer than before. He also saw to his defenses and provided refuges for his menaced people; by the early tenth century, every village in Sussex, Surrey and Wessex east of the River Tamar, was within twenty miles of a fortress. Thus a coherent system of national defense was built up. Though it was completed under Edward, his son, the scheme was Alfred’s and he began its implementation. As for the navy, he ordered the making of warships that were swifter, steadier and nearly twice as long as those of the Danes; he gave careful consideration to their design and they were constructed to his specifications.

His aim was to prevent the two companies in which the invaders sailed from joining forces; he took up a position between their camps at Appledore and Milton, near Sheppey. First he forced the smaller body at Milton to sign a treaty and leave for Esse ; then in late spring 893, the militia under his son Edward met the larger force on land at Farnham and defeated them. The Danes took refuge on an island in the Thames. Meanwhile, Alfred, moving from the west, was held up by the news that a host from Northumbria and East Anglia was attacking Exeter. Edward, reinforced from London, managed to hold the Danes on the island till they agreed to retire and join their allies in the east. It gave Alfred a respite, but a dangerously large number of Danes was thus concentrated in Essex.

Alfred the great dies but foundations are laid

The struggle that now ensued was the most exacting that Alfred, in a lifetime of war, was ever to face. His resources could not last forever, so he was forced to fall back on a desperate expedient. The Danes, a united host, seized the deserted Roman town of Chester, intending to use it as a base against English Mercia, but they found nothing to sustain them; Alfred had burned the corn and slaughtered the cattle. They had to withdraw from the scorched earth and turned to Wales, where they stayed until the summer of 894. Then they made their way eastward across England to Mersea, where they established a post some twenty miles north of London. Alfred, not daring to take the smallest rest from the apparently endless fight, managed to dislodge them in the summer of 895 — and achieved a resounding success. For the first time, the Danes seemed daunted by the courage and resolution of the English King. They sent their women home and themselves, made a forced march across the country to the Severn. Many of them left England; some made their way back to Danish East Anglia. Alfred could at least feel that a united and peaceful England was a real possibility.

This account of Danish movements is needed to bring out how shifting and varied a threat Alfred had to counter and the flexible strength he showed in meeting the many threats. A navy had been inaugurated as a matter of settled policy. When he died on October 26, 899, the English were still on the defensive; but a solid basis had been built for checking the Danes and for ultimately unifying the Danish and English areas in a single kingdom.

His greatness appeared as much in his educational as much as in his military and administrative work. No other king of the Dark Ages had such a desire to master the available culture and hand it on to his people. A personal urgency drove him to explore the problems of fate and free will, to find out how a man came to knowledge and how the universe was ordered. His own long struggles, with their many setbacks and problems, aroused in him a need to grasp the thought of the past, so that he could use it in shaping the future; he was stirred with a true reverence for human achievement, by initiating a series of translations from the Latin, he founded English prose literature. In the preface to the first of his own translations, he described how low learning had fallen; very few of the clergy, south of the Humber, knew what their service meant in English, or could turn a letter from English into Latin. By 894, when he wrote, there were once more learned bishops and a group of literate clerics, with whom he worked at a considered scheme of education for his people.

His biographer Asser, who had come from St. David’s, tells how Alfred’s curiosity had been awakened by two visits to Rome, before he was seven and how he set out to learn Latin between 887 and 893. Alfred’s own translations began with a work by Pope Gregory the Great, Pastoral Care, on a bishop’s duties; then came Orosius’ history of the ancient world and Bede’s Ecclesiastical History. In the Orosius, Alfred expanded many passages, drawing on his own experience and on that of travellers, from whom he got information on the peoples of northern and central Europe; as a work of systematic geography the book is remarkable for its time. He then moved from the factual sphere to deeper matters, translating Boethius’ On the Consolation of Philosophy, the work of a sixth-century statesman, awaiting death after an abrupt turn of fortune. He was sympathetic to its creed, that a man should rise above fate, convinced that Boethius gave a Christian value to stoic ideas. Finally, he rendered the first book of Augustine’s Soliloquies, into English.

He thus did more than provide a primary basis for a system of secular knowledge and an outlook on life, which as expressed by Boethius, did much to harmonize ancient thought with northern heroic tradition. He also carried out the difficult task of creating the instrument of English prose. Slowly, the language matured and became capable of expressing a wide range of thought. Moreover, near his reign’s end, he issued a legal code into which he introduced the Golden Rule from St. Matthew. Though primarily transitional, his code included arrestingly new features for that age: provisions protecting the weaker members of society against oppression, limiting the blood feud and stressing the bond of man and lord. It strongly aided the transformation of the tribal type of noble into the feudal type. The next two centuries were to see, all over Western Europe, the growth of conditions in which men sought lords and lords sought men: and Alfred’s code facilitated this trend in the specific English form in which the national king played a key part. In the code, indeed, we see the unique qualities – that marked the national monarchy which Alfred did so much to create. The code appeared at the end of a century, in which no other English king had issued laws and the other kings of Western Europe, were ceasing to exercise the legislative powers traditionally theirs.