The Chinese grew a new empire in the east, after the death of Alexander the Great.

The empire of Cyrus and Xerxes was vast. The empire left by Alexander on his death was even larger and it did not outlast its founder. The most obvious reasons for its immediate breakup were the lack of overall homogeneity, the variety of individual characteristics and political traditions in the area it covered and the Virtual impossibility of establishing a strong central authority to hold it together. The theme of empire is a recurrent one throughout this volume: Xerxes, Alexander, Hannibal, Shih-huang-ti and lastly Augustus — all these men commanded empires. If we seek a key to the relative endurance of such empires, we should look for a durable and comprehensive administration. The great emperor Shih-huang-ti thoroughly organized the administration of his empire and even though his dynasty was overthrown, the essential framework of the Chinese state remained. We see that after the milestone of the battle of Actium, Augustus was to devote the greater part of his energy and ability to developing and improving an administration that would provide a lasting basis for the Roman Empire. Alexander’s successors were more concerned with dividing the Near East among themselves than with pushing the territorial limits of their empire, as Alexander had done, farther toward the mysterious East, as yet largely unknown to them.

Contacts did undoubtedly exist between the ancient Near East and China. Some scholars have sought to trace Mesopotamian influences in early Chinese culture, but they were extremely tenuous. However, a great civilization had been developing there from the second millennium B.C., and with a significant epoch in it. In preparation for understnading it, we must consider some of the fundamental aspects of Chinese civilization.

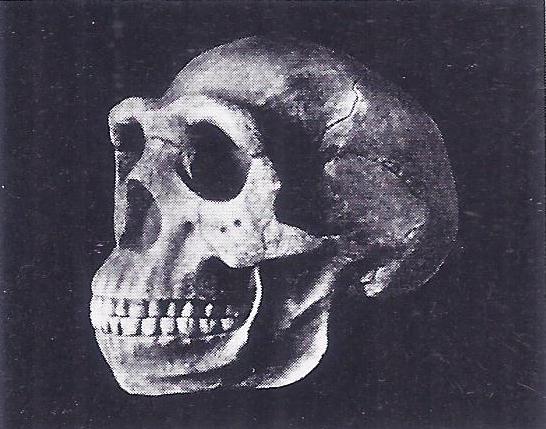

Prehistoric Chinese

China has provided evidence of one of the earliest precursors of the human race (homo sapiens). In 1929 at the village of Chou K’ou Tien, about 26 miles southwest of Peking, skeletal remains were found of the so-called “Peking Man” (Pithecanthropus pekinensis). With a cranial capacity of about two-thirds of homo sapiens, this hominid, lived about 300,000 B.C., made crude tools of stone and used fire. However, despite this early start, the subsequent development of culture in China during the Palaeolithic and Neolithic period remains obscure, chiefly because there has been relatively little archaeological excavation.

The history of civilization in China is only adequately documented by archaeological data from the Shang Dynasty (c. 1500 – 1027 B.C.). Later Chinese literature included a rich mythology which tells of many emperors, beginning from 2356 B.C. As in similar records of other early peoples (eg. the Sumerian King List and the genealogies in the Book of Genesis), incredibly long reigns are attributed to these emperors, who generally appear to have been of the culture-hero type. There are also a number of flood-myths, probably because the earliest centres of civilized life were in the area of the lower course of the Yellow River.

“Great Shang”

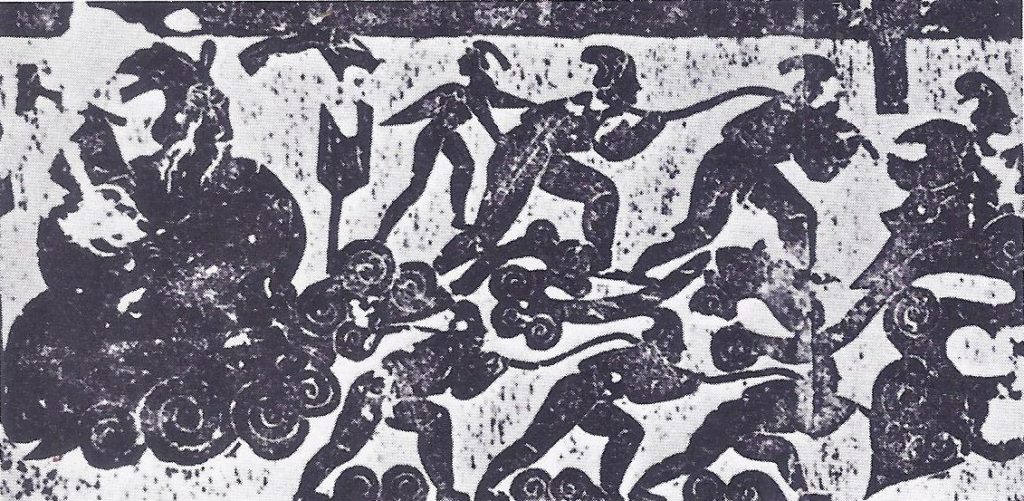

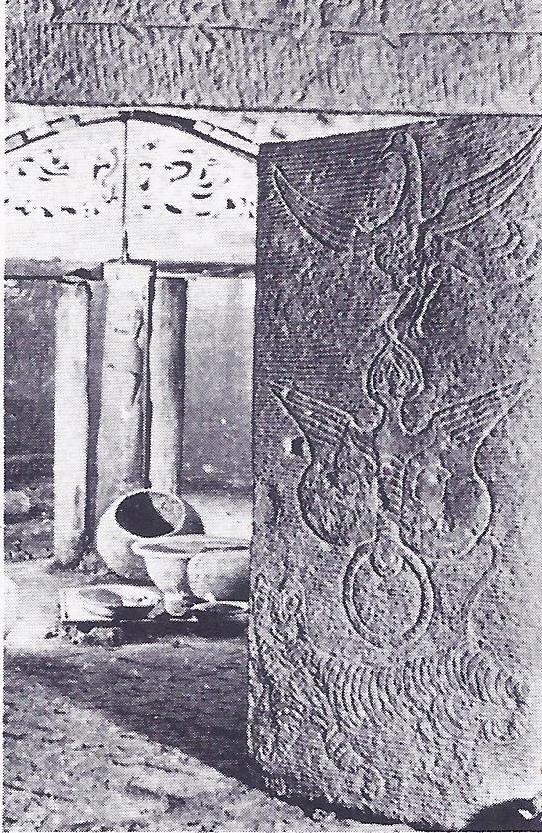

The most illuminating information about the culture of the Shang Dynasty has come from the excavation of its capital city, known as “Great Shang,” near Anyang in north Honan, which dates from the twelfth and eleventh centuries B.C. The most spectacular finds have been the “royal graves,” which parallel, in the richness of the deposits and the number of skeletons, the “royal graves” found at the Sumerian city of Ur, in Mesopotamia. The remains of chariots, horses and their drivers show how important it was considered for the dead lord to take his transport with him into the tomb. The fine ritual bronzes which were found, some decorated with the celebrated t’ao t’ieh pattern, show the high quality of contemporary craftsmanship and the existence already of the distinctive characteristics of Chinese art.

“Oracle Bones”

Another kind of evidence, less impressive in appearance but of great historical significance, has been the so-called “Oracle Bones.” It was apparently the practice at Anyang for augurs to apply a heated bronze implement to selected animal bones and the resultant cracks were interpreted as answers to questions previously asked. These questions and answers were often inscribed on the bones and constitute the earliest extant evidence of Chinese writing.

Chinese Ancestral Worship

In primitive Chinese thought, ancestor worship also involved a deep attachment to the soil, particularly to that bit of it where each family lived. It was the ancient custom to place both the newborn and the dying on the earth, thus symbolizing the need for contact with it at these two crises of man’s life. In the primitive rural communities of China it was the custom also for marital intercourse to take place in the southwestern corner of the house, near to where the seed-corn was stored and the dead, too, were buried close to this spot. Such customs sprang from the belief that the “family stock” lasted as long as the earth upon which the family lived. Thus, at any given moment, the greater part of the “family stock” lay buried in the family soil, with the living members, as it were, forming the individualized portion active above ground. Within the ordinary family this sense of integration was expressed in a devoutly practiced cult of its ancestors. Their memories were preserved on tablets in the ancestral shrine, poor and meager though it may have been. On the son devolved the duties of being the chief mourner of his deceased father and minister of his mortuary ritual, while the grandson represented his deceased grandfather at the family cult. With the development of the ancestor cult in the feudal states of ancient China (c. 722 – 481 B.C.), the family of the ruler came to epitomize the various families of the state. The primitive connection between mankind and the soil was carefully preserved by siting the ancestral temple of the ruler in the seignorial town, close to the altar of the gods of soil and harvest.

Yin and Yang

It was during the feudal period of the later Chou Dynasty that another idea which reflects a basic intuition of the Chinese mind, developed and found expression — the idea of Yin and Yang. This concept saw all cosmic existence as the product of an alternating rhythm of two complementary creative forces. The yin force or principle was regarded as feminine; it was associated with darkness, softness and inactivity. Yang was the male principle, characterized by light, hardness and activity; it was also associated with heaven, whereas yin was of the earth.

Chinese Explanation of Human Nature

A yin-yang dualism was also used to explain human nature. Man was conceived with two souls which together with the body constituted him a living person. The yin-soul was identified with the primitive kuei; because it was of earthly origin and associated with the body from the moment of conception. During the individual’s lifetime this yin-soul was called the p’o, and after death the kuei; it lingered on near the tomb but gradually faded to nothing. The yang-soul was regarded as the animating principle, which came from heaven as air or breath. It announced its presence in the first cry of the newborn infant and it left the body as the last breath at death — there was a special ritual used by relatives for recalling this soul before it departed too far from the body. The yang-soul was known as the hun during life and shen after death.

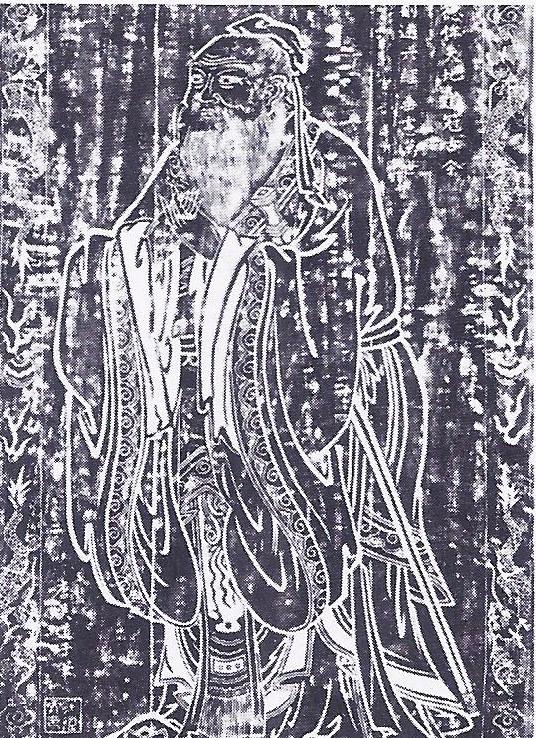

Confucius

The greatest figure in Chinese culture has been K’ung Fu-tsu or Confucius, as he is known in the West. He is known to have lived from 551 to 479 B.C., mainly in the small, but cultured state of Lu (now in modern Shantung). Although his name has become associated with Confucianism, which is often regarded as the traditional religion of pre-Communist China, Confucius was not a religious prophet or teacher as, for example, were Moses, Zarathustra or the Buddha. Indeed, according to tradition, he definitely refused to discuss religious or metaphysical questions concerning divinity or human destiny. Confucius was essentially an ethical teacher. He taught that there was a Tao, or Way of Life, prescribed for men to follow, in order to maintain the proper balance or harmony that is fundamental to social happiness and the wellbeing of mankind.

Chinese Love of Ancient Rites

Confucius lived at a time when the old feudal society was breaking up, with resultant confusion of ideas and standards, strife and injustice. He seems to have belonged to, or became identified with, the Fu. These formed a scholar-class who were experts in the performance and interpretation of religious rites and exponents of a traditional learning. Looking back to what seemed the Golden Age of the Chou Dynasty, Confucius concluded that the proper observance of the ancient rites was necessary to integrate and preserve an ordered society. This Confucian view of the past profoundly affected the earliest extant records of Chinese history, particularly of the early Chou Dynasty. For these are largely idealized accounts of the establishment of the institutions and customs which Confucius and his followers approved.

Ti’en

Confucius certainly believed that the Tao or Way, which he presented, had divine authority, but his View of deity seems to have been essentially impersonal. Instead of using the ancient term Shang Ti, the Supreme Ancestor-Spirit or High God of the Shang Dynasty, he preferred T’ien (Heaven). He did, however, associate T’ien with a number of moral qualities, so that it does not appear only as a cold cosmic entity. Ritual in its various social forms, from the official sacrifices offered by the ruler to the mortuary service, owed by the individual to his ancestors, was essential to virtue.

Confucianism

Confucius achieved meager success during his lifetime, but his Way of Life appealed to the Chinese temperament, for his reputation steadily grew until he was recognized as China’s greatest sage. He was honoured by other high-sounding titles and temples were dedicated to him; by some he was virtually regarded as a deity. There has been much discussion as to whether Confucianism, as the movement that stemmed from his teaching, should be described as a religion, for it lacks many distinctive religious attributes. Some scholars have preferred to call it an ethico-political philosophy.

Taoism

The idea of the Tao or Way, which Confucius invoked, was ancient and fundamental in Chinese culture. Confucius was primarily concerned with its social significance, although he was careful to emphasize its divine derivation. His idea, interpreted rather as an all embracing cosmic process, was developed by other sages as a rival faith and practice; it appealed to many who sought a more metaphysical creed than offered by Confucius and his disciples. Known as Taoism, with Lao-tzu as its legendary founder, this movement was based on the Chinese belief that man is a part of nature.

In time this Taoist belief produced a kind of nature-mysticism and these ideas also inspired some beautiful painting, in which the Taoist sage merges into a landscape of mystical loveliness. Taoism, at its best, demanded of its devotees a high standard of intellectual ability as well as a capacity for mysticism; but because these qualities were not always to be found, the movement easily declined into forms of popular superstition. In this way, Taoism helped prepare the gradual establishment of Buddhism in China.

Sixth-century climacteric

Our milestones of history show the development of civilization throughout the world and it is therefore worth noting here a curious but inexplicable phenomenon. The sixth century B.C. witnessed the beginnings of some of the great religions of mankind: Gautama, the Buddha, lived c. 563-483; Zarathustra was born about 570; Confucius about 551 and the foundations of Judaism were laid after the return of the exiled Jews from Babylonia. In the sixth century also came the dawn of a different movement which in the distant future was destined both to undermine and aid religion — in the cities of Ionia, Greek philosophy was born.