One of the young Athenians who must have taken a good deal of interest in Draco’s writing down of the laws was Solon. He came of a good family. His father had been extravagant and this had prompted Solon to become a foreign trader in order to repair the family fortunes. There was no question of his considering himself one of the oppressed. He was a “have” not a “have-not”. Yet Solon was destined to repeal almost all of Draco’s laws and to set Athens on the road to democracy.

We first meet Solon as a poet, patriot and soldier. The possession of the island of Salamis was in dispute between Megara and Athens. Athens, to Solon’s disgust, renounced her claim. Solon rushed into the market place and recited a poem in which he appealed to the Athenians to reverse their decision and conquer the island. The poem had the desired effect. Solon was chosen to lead the attack and eventually Salamis became part of Attica. A little over a century later the decisive sea-battle of the Persian wars was fought in the stretch of water which separated Salamis from the mainland.

After 16 years the trees begin to bear olives, coloured greyish green, the size of a damson. They are eaten with bread or crushed to make oil which is used for cooking. The ancient Greeks also used olive oil in lamps and for rubbing on their bodies (they had no soap). As well as being indispensable at home, the oil provided a valuable export.

Meanwhile discontent due to poverty and debt, had reached such a pitch, that the need for firm action was clear. Solon was liked and trusted. When he was elected archon in 594 B.C. he was able to begin a programme of reform.

Solon’s first act was to free all those who had enslaved themselves on account of debt and make it illegal for any citizen to do so again in the future. Other measures were aimed at checking extravagance. For instance, not more than a certain sum might be spent on funerals or on the dowry of a bride. Last of what may be called Solon’s restrictive measures was the prohibition of the export of corn. There was not sufficient for home consumption but merchants had been exporting because they found it more profitable. Henceforth only olive oil might be exported.

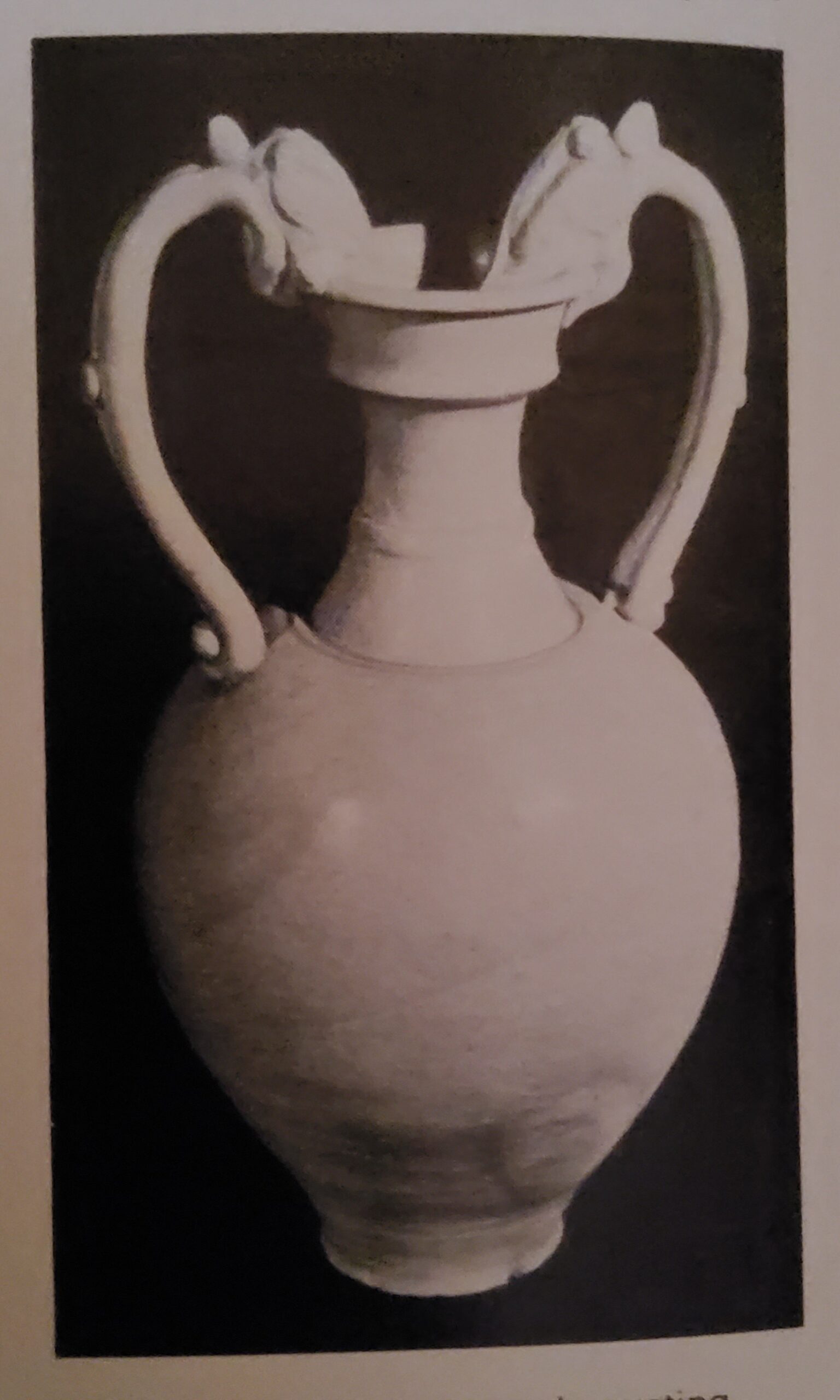

Solon’s constructive measures were intended to encourage manufacturers. Every father was compelled to teach his sons a trade and foreign craftsmen were encouraged to settle at Athens (though they did not become full citizens). Corinthian pottery was already famous. Vases, bowls and jugs made from the reddish Attic clay and decorated with black figures now began to rival the Corinthian ware. Incidentally, this black-figured pottery and the red-figured pottery which succeeded it in the 5th century B.C. is one of our best sources for finding out what Athenians wore and how they lived. Many of the drawings in this book are based on black or red-figured pottery, but the figures cannot be copied exactly because in the original they were on a curved surface.

Having freed the poor of debt and laid the foundations of industrial prosperity Solon arranged that the privileges and responsibilities of government should be more equally shared. Even the poorest citizens were to be members of a People’s Assembly and they might also serve as jurors in a People’s Law Court. This does not mean that Solon led a revolution which overturned the aristocracy. He was, after all, an aristocrat himself and he left the aristocrats still powerful. When democracy developed fully at Athens during the 5th century Solon was regarded as its founder.

It is said that, having made his laws, Solon left Athens for ten years to give the city a chance to test them. He travelled widely, visiting Egypt, Cyprus and Lydia. The story of his meeting with King Croesus of Lydia cannot be quite true, because Croesus did not become king until 560 B.C., but it is a story which should be known.

Croesus made a great display of his wealth when Solon visited him. Solon, however, was not impressed. Croesus then had him conducted round the royal treasuries, but Solon still did not burst forth into the expressions of amazement and congratulation which were expected of him. Croesus then said, “Tell me, Solon, have you ever known a happier man than I?” “Oh, yes” answered Solon and proceeded to describe an Athenian, father of a family, honest and fairly well off, who had died fighting for his country. “Anyone else?” asked Croesus, whereupon Solon described two Athenian youths who had died on the same night after dutifully helping their mother the previous day. When Croesus became angry at finding no place for himself in Salon’s list of happy men, Solon explained that the Greeks did not believe in congratulating a man on his good fortune, because they knew that later there might be a change for the worse. “We only call a man happy” he added, “if he has gone on being happy until his death. You might say that we look on life as a wrestling match. We do not believe in awarding a crown of victory while the contestants are still grappling with one another. We wait till the end. ”

Like many people who are given good advice, Croesus did not like it very much at the time. Some years later however his kingdom of Lydia was overthrown by Cyrus the Persian and Croesus found himself bound upon a pyre, about to be burned to death. Solon’s words came back to him. “We wait till the end”. He saw the point of it now. “O Solon! Solon!” he cried. Cyrus heard him. Was this some God, he asked, this Solon on whom Croesus was calling? Croesus was unbound and brought before his conqueror. When he heard the story, Cyrus was so moved that he cancelled the death sentence and Croesus became one of his firmest friends.

When old Solon came back to Athens after his travels he found people far from contented. There was bitter party strife and not long after his return the city which Solon had set on the road towards democracy found herself under the rule of a tyrant.

The word tyrant in Greek history has a special meaning. Many of the city states passed through a period of tyranny, which meant rule by one man, instead of rule by members of the wealthiest families. This one-man rule was often less cruel than rule by the wealthy.

The tyrant looked after the interests of the poor in order to win their support, but not all tyrants were wise and humane. One of them, Phaleris of Acragas in Sicily (c. 560), made a name for himself by burning his enemies in a brazen bull. It is because of that kind of action that the word “tyrant” in English is now only applied to ruthless rulers.

Peisistratus, who now seized power at Athens, was one of the humaner sort of tyrants. He treated Solon as a distinguished elder statesman and Solon, now nearly eighty, does not seem to have protested against the new regime. He did not see very much of it, for in 559 he died. Did he die happy, according to his own standard? Had he been wise in leaving Athens, instead of staying to see that his new laws were kept? Perhaps not. On the other hand if his principle “Wait till the end” is carried a step further and you take it to mean “Wait for the judgment of history”, Solon is happy indeed.