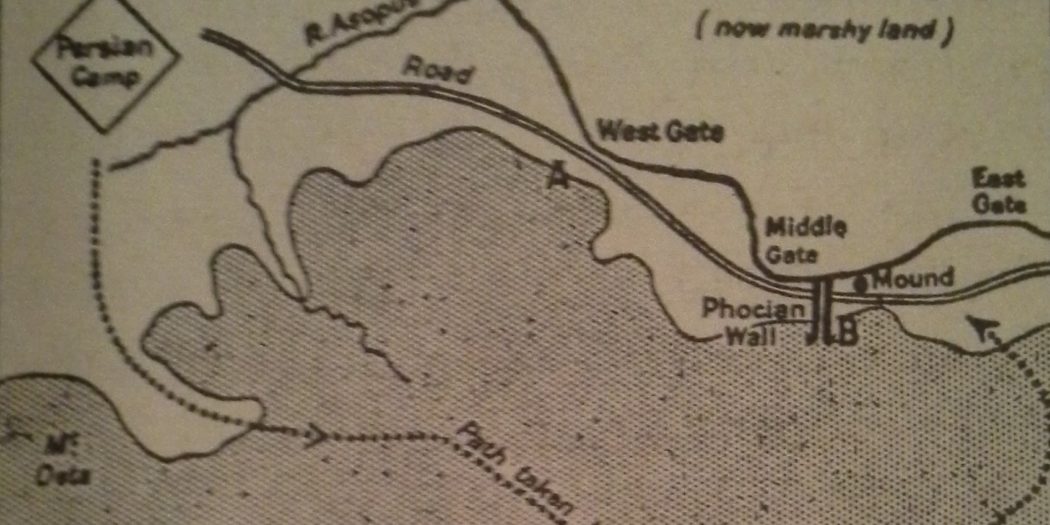

The first narrow place where the Persians might have been held was the pass of Tempe in the north of Thessaly. A force was sent there but withdrew when news came that the Persians might take another route and outflank them. Thessaly was thus abandoned to the Persians; but they were not to be allowed farther south without a fight. The only route lay through the pass of Thermopylae. Here Leonidas the Spartan, who was Commander-in-Chief of the Greek forces, decided to make a stand, while the combined Greek fleet kept watch near Artemisium on the Persian ships, which were sailing along the coast in support of their army.

Thermopylae is still a position vital to the defence of Greece, but it is no longer a narrow pass. The sea has retreated. When Leonidas and his men took up their position it came close to the foot of the mountains, leaving only a narrow passage between.

Xerxes was surprised when he was told that the pass was held. He was inclined to be contemptuous when a spy reported that the enemy troops were engaged in gymnastics and were combing their hair. In fact the spy had been looking at the cream of the Greek force — three hundred Spartans. It was the Spartan custom to wear long hair and to prepare for battle in this apparently lackadaisical fashion. These same men had been warned that the arrows of the Persians would be so numerous as to darken the sun, to which one of them had replied: “Excellent. We shall have our fight in the shade then.”

Xerxes did not attack for four days, since he still expected the Greeks to retreat without fighting. On the fifth day however he sent a force with orders to capture the Greeks and bring them back alive. This force failed. They brought no Greeks back alive. They would have been glad to bring back their own dead, but there were too many of them. On the sixth day, therefore, the bravest of the Persian troops, who were called the Immortals, hurled themselves against the Greeks; but even they could not break through.

It was then that a Greek traitor came to Xerxes offering to show the path over the mountains which would make it possible — he hoped — to take the Greeks in the rear. The offer was eagerly accepted and a Persian force set out.

Leonidas had not forgotten this path. On the contrary, it was guarded by a thousand Phocians who lived in that part of the country and who had volunteered for this particular duty. A commander could hardly have done more to secure his position — a thousand Phocian men guarding a narrow path and knowing that if they failed in their duty their homes would be the first to suffer. Yet it was these men who fled at the first sight of the Persians and let them through.

When Leonidas heard what had happened, he realised that his position was hopeless and sent away most of his force. Then, with his three hundred Spartans and some others, he fought once more in the pass and died there.

Thermopylae was a Persian victory but the Persians paid so dearly for it that succeeding generations regarded Leonidas as one of the saviours of Greece. The nobility of his men has made posterity forget the ignoble Spartan system which produced them and why not? For this brief moment of Greek history Sparta is the hero.

The three hundred did not think of themselves as fighting for an ideal. They were simply doing their duty. So, when Simonides of Ceos (556-467) composed their epitaph, it was not of a fight for freedom, but of obedience which he wrote:

Make known among the Spartans,

passer-by,

That here, obedient to their laws,

we lie.