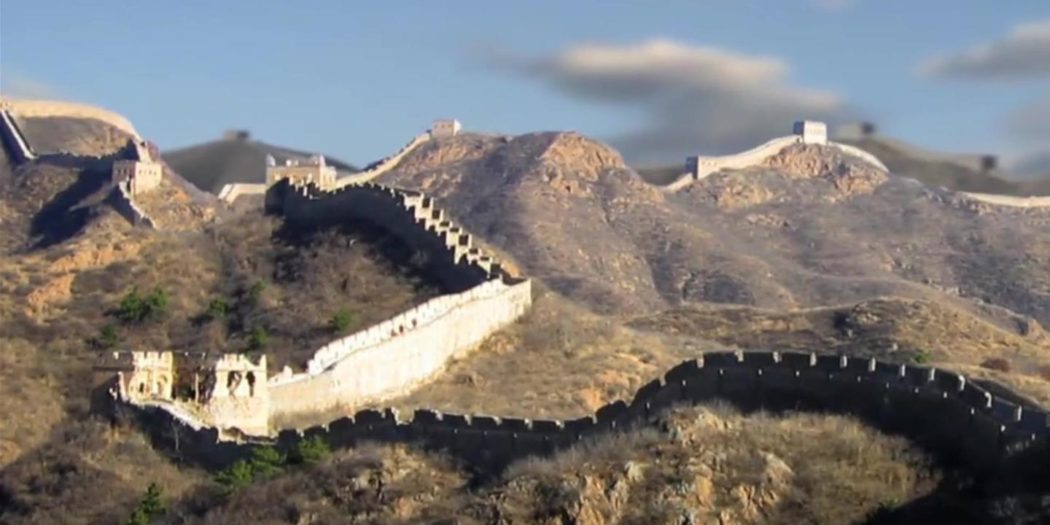

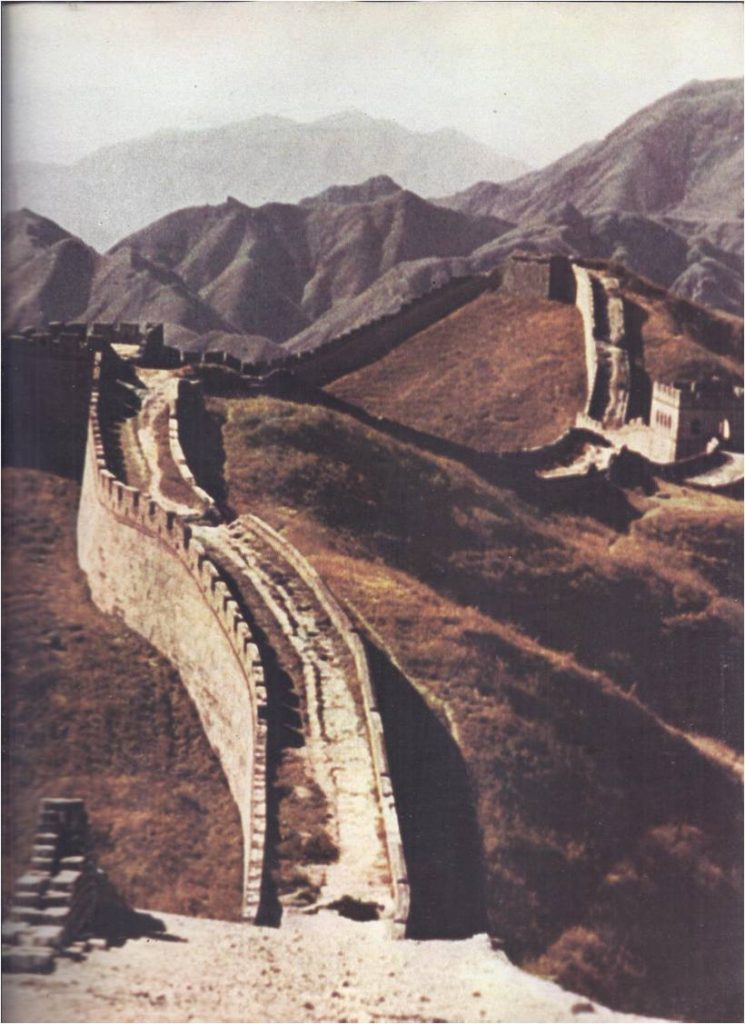

The Great Wall of China is probably the world’s most stupendous monument to human ingenuity, human industry and purportedly is the only one of man’s works that could be seen from the moon.

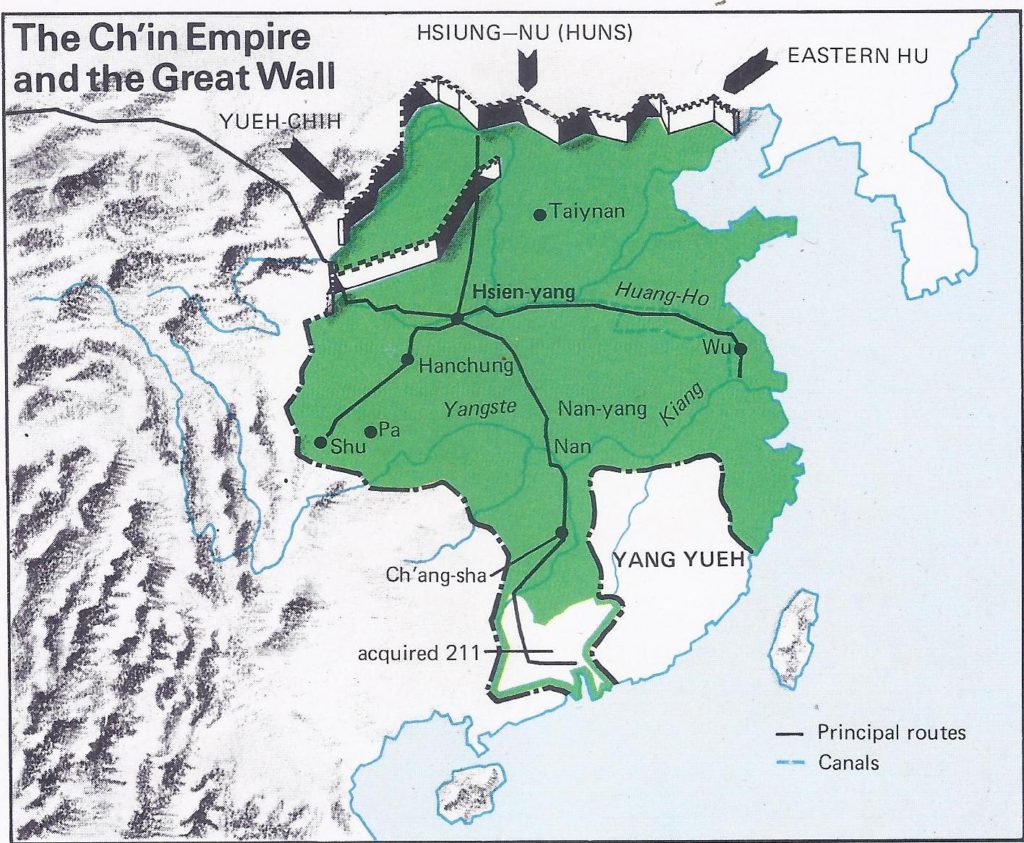

Finding his country a patchwork of desperate states, Shih-huang-ti, the first Emperor of China, imposed upon it unity and coherence. Centralized administration demanded swift communications, so a vast network of roads and canals was thrown across the country. Weights and measures were standardized and the same writing script introduced throughout the land. Unity, however, was of little use without security and to protect his new empire from the repeated invasions of Turco (Mongolian hordes), Shih-huang-ti built an immense wall that survives to this day. Across hill and valley, mile after mile, the mighty bastion is a vivid testimony to the will power of an absolute monarch and the imagination of a creative genius.

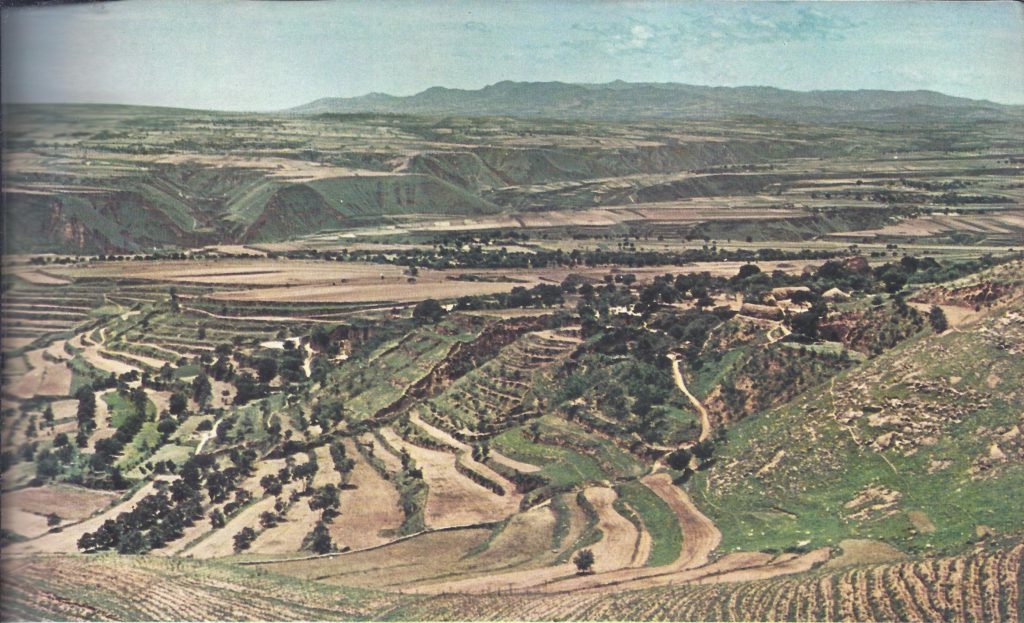

The Wan-li ch’ang ch’eng or Wall of Ten Thousand Li (a li is approximately one-third of a mile) forms the country’s northern boundary, extending some 1,400 miles from the Gulf of Chihli in the east to the sources of the Wei River in the far west of Kansu province.

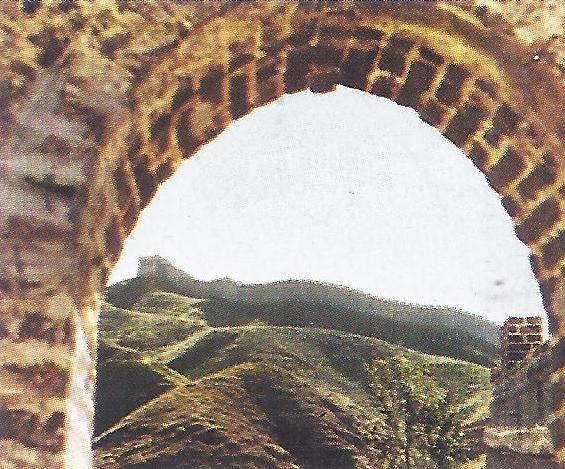

Even today, centuries after its construction, the Wall remains an awe-inspiring sight. It climbs the sides of ravines and crests, the watersheds of mountain ranges, doubling back on itself so frequently that its actual length is more than double 1,400 miles. In some stretches, particularly in the desolate desert regions of the far west, the Wall has been reduced to mere mounds of earth a few feet in height; other portions hundreds of miles in length are still in excellent repair — their stone, brick and mortar facings intact. The average height of these sections is twenty feet and at top they are wide enough to permit six horsemen to pass abreast.

Although the Great Wall has been repaired and enlarged many times, the existing structure is mainly the result of restoration work undertaken during the Ming dynasty (A.D. 1368-1644). All reliable Chinese sources attribute the original building to the Ch’in dynasty ruler Shih-huang-ti, the self-styled First Emperor of all China. His imperial reign lasted only eleven years (221-210 B.C.), but for the preceding twenty-one years Shih-huang-ti had ruled the semi-barbaric border state of Ch’in in northwest China. With the assistance of able ministers, he had turned the full energies and resources of the Ch’in state to production, defense and his kingdom rapidly became an irresistible military power.

In the year 211 B.C. the Ch’in ruler defeated the last of the feudal states into which China had been divided for centuries and proclaimed himself the First Emperor of China. Shih-huang-ti set himself the task of unifying his vast territories under the control of a strong centralized government and thus ending centuries of all but incessant internecine strife. Shih-huang-ti soon realized that the unification and pacification of his empire would be thwarted unless he could ensure the defense of his northern frontier, vulnerable to the constant incursions of China’s traditional enemies, the warlike, nomadic Turco-Mongolian tribes who inhabited the northwestern Steppes. Those barbarians, who “moved from place to place according to the water and grass, they had no walled cities or towns, settled habitation or agricultural occupation,” had united under the Hsiung-nu, or Hun tribesman, by the time of the First Emperor.

From the beginning of his reign, the Emperor had been forced to send one expedition after another to drive back the swiftly moving Huns, who retreated over the wide Mongolian plains after each successful raid. Conquering the Mongols proved impossible; containing them within their own territories was all Shih-huang-ti could hope to achieve. To do so he embarked upon a construction project unparalleled in world history: the building of the Great Wall.

Shih-huang-ti was determined to construct a chain of strong fortifications and watchtowers along the entire length of his northern frontier and then to join them together by a massive wall. In 215 B.C. he dispatched General Meng-T’ien to the northern frontier with an army of 300,000 labourers and an uncounted number of political prisoners, convicted felons and other elements of the population that were considered dangerous or unproductive. There were already hundreds of miles of fortifications in existence along China’s northern borders, built in earlier times by the states of Ch’in – Chao, Wei and Yen – to protect themselves from the Huns and the eastern Hu tribes. Those barriers were well maintained and wherever possible, Meng-T’ien’s engineers simply rebuilt and strengthened earlier fortifications.

Though there is little reliable information, numerous legends testify to the immensity of the builder’s task — its appalling toll on human life and suffering — and the remorseless speed of the Wall’s construction. It has been estimated, for example, that if the materials used in building the Wall were to be transported to the equator, they would provide a wall eight feet high and three feet thick, encircling the entire globe. The Wall reportedly had 25,000 watchtowers within signaling distance of one another, each capable of accommodating one hundred men. Between the watchtowers, two parallel furrows, about twenty-five feet apart, were chiselled out of the solid rock. On this foundation, solid, squared granite blocks were then laid and these were topped by two parallel courses of large bricks. The inner core was then filled with tamped earth. According to legend, the unwieldy granite blocks were often tied to teams of goats, who dragged them up the almost inaccessible ridges. It has been estimated that at one time roughly one-third of the able-bodied men of the empire were engaged either in building or defending the Wall, or in conveying the necessary supplies to the inhospitable regions that the Wall traversed.

So long as it could be effectively garrisoned, the Wall undoubtedly provided the rich agricultural plains of north China with some protection from Hun incursions, but it served another purpose as well. The Wall proved an effective barrier to the dissident indigenous groups within the empire who had been dispossessed of their lands and desired, to defect to the enemy. Chinese scholars and peasants alike, had much to offer the less sophisticated northern barbarians in the way ‘ political, agricultural and economic expertise, and Shih-huang-ti -was resolved that all defection attempts by sizeable groups should be frustrated.

The Wall solved another of Shih-huang-ti’s domestic problems as well. Decades of almost ceaseless warfare had led to the creation of a huge standing army. Those soldiers, spread over the empire and inured to fighting, might easily prove a threat to the centralized government. Thus the garrisoning of the Great Wall served a dual purpose, for besides protecting the frontier, it also kept a large part of the army permanently occupied some distance from the capital. In addition, it solved the problem of providing useful employment for China’s vast numbers of landless vagabonds, prisoners and disillusioned scholars.

The sheer logistical problem of supplying the garrisons with food and equipment was an enormous drain on the economic resources of the empire, however. Apart from the Yellow River few of north China’s rivers were navigable for an appreciable distance and the loaded supply barges had to be manhandled upstream against swiftly flowing currents. Carts traveling the barren regions often used up many of their supplies before reaching their intended destinations. Shih-huang-ti attempts to supply provisions to the troops stationed along the Great Wall were a contributory cause in the speedy collapse of his empire.

Nevertheless, the Great Wall was a mighty material symbol of empire, an indication that for the first time in East Asian history, a great power structure had arisen under the unified control of an absolute monarch. By almost every act, Shih-huang-ti repudiated China’s centuries-old feudalistic system. He saw himself as the inaugurator of a new era and he ruthlessly destroyed the feudal states and their territorial magnates. The Emperor divided the lands into thirty-six (later forty-one) districts, in which both military and civil authorities were responsible to the Emperor himself. In those districts, the influence of the Confucian scholars was severely curtailed and in 213 B.C. Emperor moved to diminish further the power of the Confucians by ordering the destruction of Confucian classics that the scholars invoked as “mirrors of the ancient golden age of universal peace and prosperity, under Sage-kings who ruled, not by force, but by virtue.” State histories, except for those of Chin and the writings of ancient philosophical schools were also destroyed.

The Confucian ideal of rule by etiquette, propriety and appeal to ancient precedents, was rejected by standardized laws, which, though extremely harsh, were applicable to all. Peasants were given the right to own, buy and sell land. Agriculture was encouraged; commerce, which Shih-huang-ti regarded as non-productive, was repressed. Currency, weights and measures were all standardized — and by fixing the length of cart axles, communications along the roads through the loess-land of north China were measurably improved. Equally important was the unification of the written language through the introduction of a simplified script — a measure that, perhaps more than any other, advanced the cultural continuity of Chinese civilization.

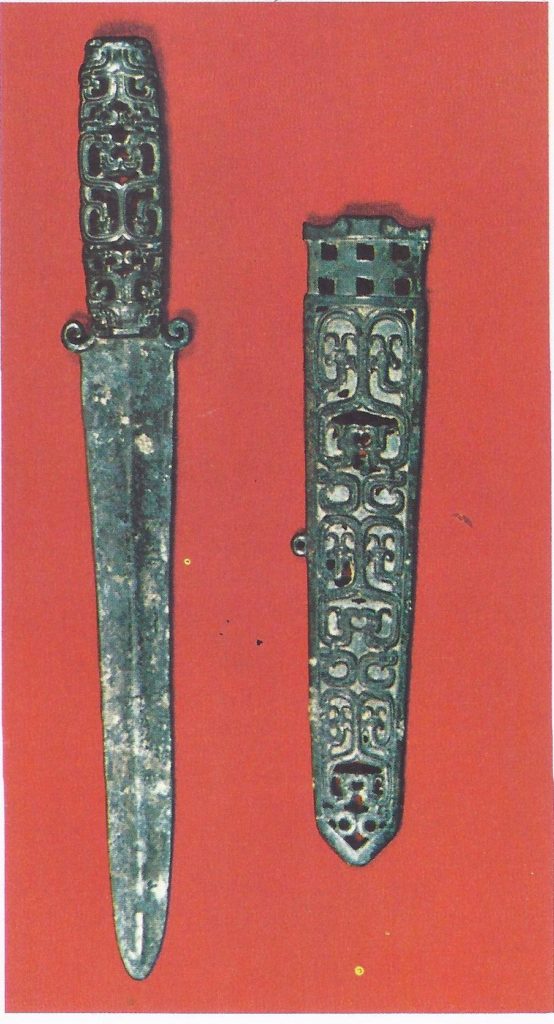

To make organized revolt difficult, the weapons that had belonged to the feudal lords were melted down and their local fortifications were destroyed. Barbarian tribes that had inhabited north China for generations were expelled, while the southern farm tribes, who lived in what are now Kuangsi and Kuangtung provinces, were brought under chinese jurisdiction by a brilliant campaign that included the digging of a twenty-mile-long cannal to connect the great river systems of central and southern China.

The building of the Great Wall was not the First Emperor’s only grandiose scheme. He put 700,000 convicts to work building a capital city, Hsien-yang in Shensi province, of a size and magnificance never before attempted. According to Chinese historians, 120,000 of the richest and most powerful families in the empire were transported to the new capital. The Emperor sought to win them over by building exact replicas of the palaces those families had left behind and by loading them with titles and empty honours. For himself, Shih-huang-ti built an enormous palace near the capital and a sepulcher under the shadow of Mount Li. Tree-lined radial roads fifty paces broad spread from Hsien-yang to all parts of the empire.

The First Emperor made frequent tours to different parts of his empire and he often ascended the sacred mountains in outlying areas to make sacrifices. Extremely superstitious and morbidly fearful of death, Shih-huang-ti became the dupe of Taoist magicians, as he eagerly sought after the elixir of immortality. Impetuous, violent, cruel and despotic, Shih-huang-ti came to believe that he was semi-divine and erected self-laudatory tablets throughout the empire. Gradually he became so mistrustful of even his closest associates that he segregated himself from his ministers and each night changed his sleeping quarters. Thus, towards the end of his life, the ruler of all China often could not be found when important matters needed decisions.

Soon after the death of the First Emperor rebellion broke out and within four years, in 206 B.C., the Ch’in dynasty came to an ignominious end. The concept of empire and the idea of the unity of all who lived south of the Great Wall were not lost, however, even in times of imperial breakdown the vision of a united China remained. A Centralized government had been established to promote large public works, exercise a monopoly over certain basic products, promote a common coinage and a common written language and maintain a large standing army.

The First ruler of the succeeding Han dynasty was astute enough to enforce most of the First Emperor’s measures. There was a partial return to the old feudal system, however, as the new monarch granted fiefs to relatives and favourites. Furthermore, in his search for capable men to staff his huge administration he found it necessary to employ those who had been trained in Confucian ideas — and during the Han dynasty Confucianism came into its own.

The Huns, powerless against the First Emperor, once more renewed their pressure. Breaking through the Great Wall at its weakest point, they swept down on to the Yellow River plain and were only bought off by a huge present of silk, wine and grain. It was not until the reign of the Han dynasty emperor Wu-ti (140-87 B.C.) that the Chinese re-established their supremacy over the northern barbarians and even expanded their empire far beyond the Great Wall into Korea and westwards towards central Asia.

The utility of the Great Wall as a means of defense has often been seriously questioned. Again and again throughout Chinese history the equestrian hordes of the Mongolian plains succeeded in detecting unguarded or weakly defended positions and poured through them, on to the north China plain to wreak untold havoc. These comparatively primitive tribes of the inhospitable northern Steppes found in the rich cities and well-cultivated homesteads south of the Wall an irresistible inducement to plunder. Their descent into China could sometimes be checked, but never permanently stopped. Only by keeping the Wall in constant repair and by garrisoning its whole length with well-seasoned and loyal troops could the government hope to keep out the intruders. In the days of the greatest of the Han, Tang and Ming emperors the Wall provided a sure bastion against the invaders, but through long periods of internal weakness it proved entirely ineffective.

For some four centuries after the fall of the Han dynasty the whole of north China was governed by barbarians. Throughout the fifth and the first half of the sixth centuries A.D. the Avars, a Mongol people variously called the Jou-jan or Juan-juan, maintained an empire north of the Great Wall extending from the borders of Korea to Lake Balkash and they continually threatened north China. In 607 the Great Wall was again fortified, but at a prodigal cost: it is estimated that a million men worked for ten days during the summer of that year — and that half of them died. Later, in the Sung dynasty, the great Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes were halted for two years by fanatical Chinese resistance; they did not break through the Wall until AD. 1209.

The Great Wall not only helped to weld the Chinese people into a great nation, but it also helped to unify the peoples of the steppes into a political and military power. The building of the Wall marks a milestone, not only in the political history of China, but in that of Asia – as a whole. It may have had a considerable effect in turning the Huns westwards to overrun Europe and thus change the course of European history. From the time that the Huns established a political hegemony over the region north of the Great Wall from Korea to central Asia, one power-structure after another rose to control that vast area. Yet none of them remained untouched by the cultural and civilizing influence of China. So strong was the cultural stability which developed in China that even when (for nearly four hundred years) north China was at the mercy of northern tribesmen, those non-Chinese conquerors gradually accepted Chinese culture and customs, merging into the Civilization of those whom they had conquered.

The same thing happened when the Mongols conquered China and founded their own dynasty. Chinese culture was immeasurably enriched by this admixture with peoples from beyond the Great Wall, but the basic structure of Chinese administration and lifestyle remained intact. In fact, neither the Mongols nor the Manchus could hope to be able to rule the vast Chinese empire without relying heavily on the Confucian scholar class.

After the Manchus took over the empire in A.D. 1644 the Great Wall ceased to be of military significance. Had the Chinese general Wu Sankuei defended the mighty fortress of Shan-hai-kuan at the eastern end of the Great Wall, a purely Chinese dynasty might have established itself in place of the effete Ming. Instead, he surrendered the fortress to the Manchu armies, who rapidly occupied the whole of north China and established their capital at Peking.

The empire of the Manchus was no longer bounded on the north by the Great Wall; Manchuria, Mongolia, Sinkiang and Tibet all remained outside it. New and entirely different enemies from overseas began to engage the attention of the Chinese government and the Wall, ungarrisoned and neglected, gradually fell into disrepair. Materials were even scavenged from it to construct the imperial tombs of the new dynasty. Today what remains of the Great Wall stands as an eternal witness to the dream of the First Emperor and great empire-builder, Shih-huang-ti.