Slaves could be imported to Italy when and where they were needed. The demand for labour was immediate and there was a much faster and more predictable solution to such a demand, than encouraging population growth or attracting the movement of free workers.

The expansion of Carthage was brought to a grinding halt when the genius of the Roman general Scipio enabled the Romans to defeat the Carthaginians decisively on their own ground, at Zama in North Africa. Hannibal lived out the rest of his life in haunted exile, forever planning to challenge the might of Rome again, whether on behalf of Carthage or one of the Hellenistic kingdoms.

Rome was now undoubtedly mistress of the western Mediterranean. The dangers that she had experienced at the hands of a Greek leader, Pyrrhus, were not forgotten, so she also determined to keep a watchful eye on the East. She set about systematically fore-stalling the rise of any potentially dangerous rival in Greece, taking the side of the weaker party against the stronger in political quarrels, to maintain a certain balance of power. Philip V, King of Macedonia, the chief aggressor in Greece, was driven out and a protectorate was set up. Greece was again aided against an “aggressor” when the Syrian Antiochus III, the Great, invaded. He was hounded into Asia Minor by a Roman army and heavily defeated. Roman influence then rapidly spread over Asia Minor.

Pergamum became a client-kingdom and discord was promoted in Syria so that no strong centralized control remained. In Egypt, the Ptolemaic kingdom was given Roman “protection” and this loose form of protectorate lasted until Egypt became an integral part of the Roman Empire after Actium, the subject of one of our subsequent chapters.

The Rise of Rome

From the ashes of Alexanders empire, the foundations of a new empire were rising, as Rome gradually filled the power vacuum left by the disintegrating Hellenistic states. For the first time, the whole Mediterranean area was to be dominated by one state.

Just as the collapse of the Athenian empire had caused Thucydides to ponder on the vicissitudes of political power, so contemporary historians were roused to speculate on the seemingly meteoric rise of Rome to world status. With the perspective of time, we can see the fundamental internal instability of the Hellenistic states, with their wandering armies and treasure-seeking princes, as one of the main causes; contemporary historians gave a schematic explanation of Rome’s success that is not entirely unrelated. They attributed Rome’s rise to the soundness of her constitution. In the neat fashion of Greek political theory, the Greek diplomat and historian Polybius (who had first-hand experience of Rome’s expansion in Greece) emphasized its “mixed” character.

With the semi-royal powers of the highest office, the consulship, combined with the oligarchic component of the senate and the democratic component of the people’s assembly, Rome had eliminated the potential for strife between oligarchs and democrats, or the dominance of single ruler-kings, tyrants or demagogues. This idealized analysis of Rome’s constitution is certainly highly optimistic — we shall see at Actium, where the Roman state was almost torn apart by a handful of individuals — but it does reflect a measure of truth about Rome’s internal stability at this time and the permanence of her political institutions that allowed her to operate a consistent foreign policy.

Rome’s Expansion

The immediate question that springs to mind when surveying the hundred-year rise of a small citystate to a position as the leading power in the Mediterranean world is how far, and from when, a conscious policy of expansion was pursued. This has been a favorite question with historians for generations. What one can observe is that the establishment of loose protectorates, rather than permanent administration, would tend to indicate that Rome was initially filling a power vacuum for her own protection as much as anything. The advantages of achieving political stability by full-scale annexation could be outweighed by the disadvantages of the cost that it entailed in men and resources.

Diplomacy was more feasible for Rome in the latter part of the second century B.C., but where there was an immediate economic “pay-off” Rome might annex territory on a permanent basis. Sicily became a “province” i.e. under the direct and permanent administration of Rome after the First Punic War. It was of strategic value certainly, but its rich grain-lands soon played a vital part in Rome’s grain supply.

The Roman Army

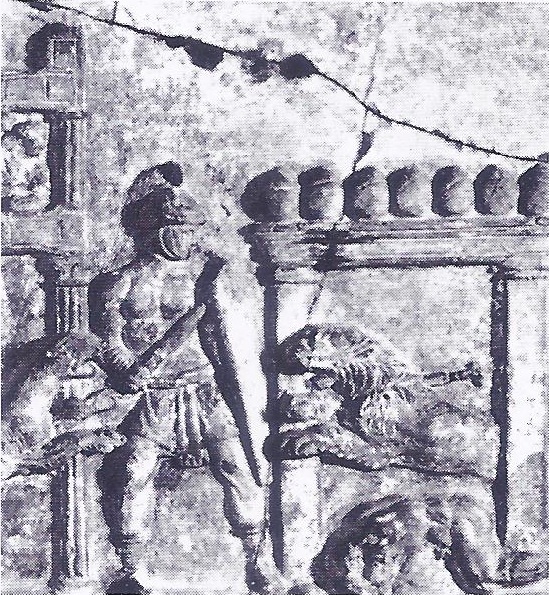

The desperate fight against Hannibal had hastened the development of the Roman military machine. It would not be long before this efficient new weapon would be used, not for the occasional skirmish or police-work to back-up diplomatic policy, but with a ruthlessness foreign to the war games of the Hellenistic rulers. Roman peace-keeping in Greece took a more aggressive turn. Macedonian influence was effectively broken at the battle of Pydna in 168 B.C., but the Achaean League in central Greece was still causing trouble. The Romans decided to crush Greek resistance once and for all: the consul, L. Mummius, obliterated the city of Corinth in 146 B.C. This was indeed a bad year for Rome’s enemies. The rising tide of opinion in the Roman Senate, which for years had been advocating the destruction of Carthage, as the only solution to the danger of Carthaginian expansion, finally won. The Roman general Scipio Aemilianus was given a mandate to destroy the city. He razed it to the ground, so that hardly a trace remained and is said to have wept when he had finished.

A by-product of this period of expansion and conquest,was the flow of spoils and money from the conquests into Rome. The treasury, which had been drastically depleted by the major war-effort against Hannibal, showed a significant surplus by about 187 B.C. One of the chief economic effects of this influx of wealth was an increase in investment in Italy, much of it going into the purchase of the most solid investment available, land. This was also where the senatorial classes could best spend their wealth, as they were barred from commercial activity. With this growing interest in land came a desire to intensify agricultural production, to take advantage of growing urban markets. This meant there was a need for more labour.

The Slave Question

Traditionally in the Mediterranean world, conquest frequently involved the enslavement of defeated soldiers and local populations. It was a question of business: a captured enemy was worth something, a dead one was not. The idea of a human being as a commodity to be exploited, which is virtually what a slave was, may seem extraordinary and abhorrent today, but in the ancient world, slavery was an accepted institution. Even the most democratic of states, fifth-Century Athens, had a large slave population. However, Rome in the Republican period, began to exploit the convention of enslaving conquered peoples on a greater scale than had occurred before. A revolt in Sardinia in 176 B.C. was crushed by a Roman general, whose boast was that he had captured or killed some 80,000 people. Most of the captives would have found their way onto the slave market. In 167 B.C., some 150,000 inhabitants of Epirus in Greece, were enslaved — the glut in slave labour that such an act must have contributed to, can only make one fear for the cheapness of human life under such conditions.

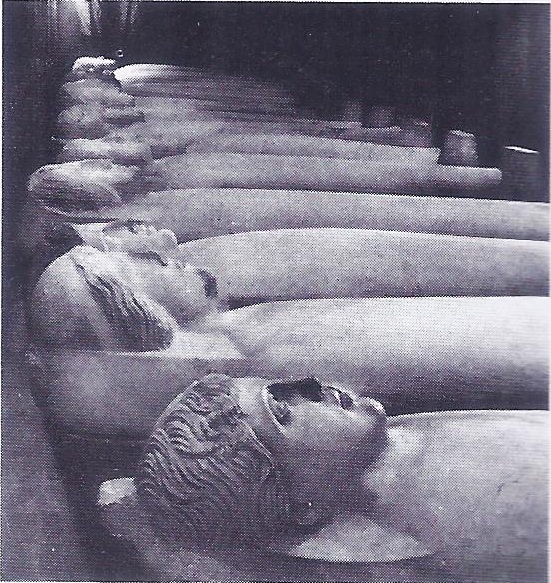

The importation of large numbers of slaves to work on the land in Italy necessitated strict, not to say brutal, control of them. Slaves were worked in gangs, often chained together. The men were often segregated from the women. The Roman writer Cato, records the grim reality of such slavery: he maintained that it was cheaper to work slaves to death and replace them, than to get less out of them by humane treatment. Slaves could also be used as raw material for gladiatorial shows, trained, cossetted and fed, until the few brief moments in the arena, where they died for Rome’s pleasure. Spartacus, was a gladiator.

Not every slave was at the very depths of exploitation. Through the accident of war, highly educated and cultured people might find themselves enslaved. This was particularly true of the Greeks who came into conflict with Rome and was still the case at the end of the Medieval period. After the fall of the last bastion of Greek culture, the city of Constantinople, several Turkish businessmen found themselves somewhat embarrassed owners of cultured and indeed noble Greeks; perplexed by their courteous deference and superior education. Meanwhile, the children of Roman aristocrats learned the refinements of Hellenic culture from erudite Greek slaves. Roman Senators, barred from commercial activities, made great use of slaves as their deputies in business. Since slaves could not legally own property, the results of their economic activity flowed back into the purses of their masters. A talented slave could also earn enough to buy his freedom eventually. The ties of personal loyalty that bound such slaves to their masters, if sometimes through fear of punishment, made them useful also as instruments of imperial administration under the Roman Empire and a slave frequently appeared as the Emperor’s personal deputy.

Thus slavery, as a legal condition that was the by-product of conquest, could span a whole range of social classes, according to the historical accident which had made individuals slaves. As a general economic system operated by the Roman Republic, it involved for the most part, the exploitation of the lower classes. The use of slaves en masse, as herdsmen, cultivators or gladiators, constituted them as a well-defined social group, and this group identity of large numbers of hideously-treated people, brought about a rebellion within the Roman state which assumed almost catastrophic proportions.