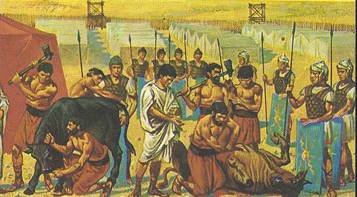

IT WAS the Sunday before Passover. The soft greens of spring and patches of wild flowers brightened the hills above Jerusalem. The holy days of the Passover, celebrating the escape of the Jews from slavery in Egypt, would not begin until the following Friday at sundown. But people were already busy preparing for it. The roads leading into the Holy City were crowded with Jews coming to attend the rites in the Temple. On the roads were also herds of cattle, flocks of sheep and carts loaded with cages of turtledoves. These were being brought to the Temple to be …

Read More »