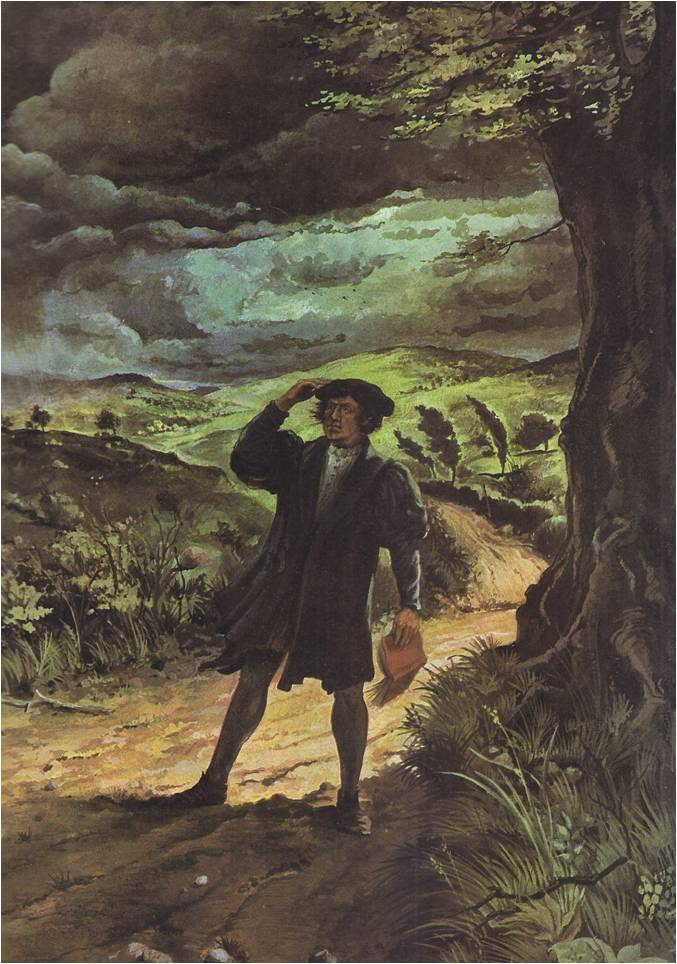

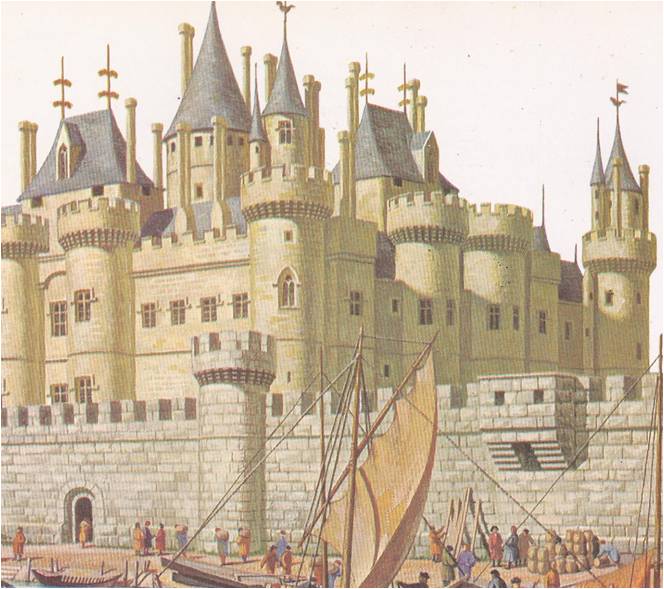

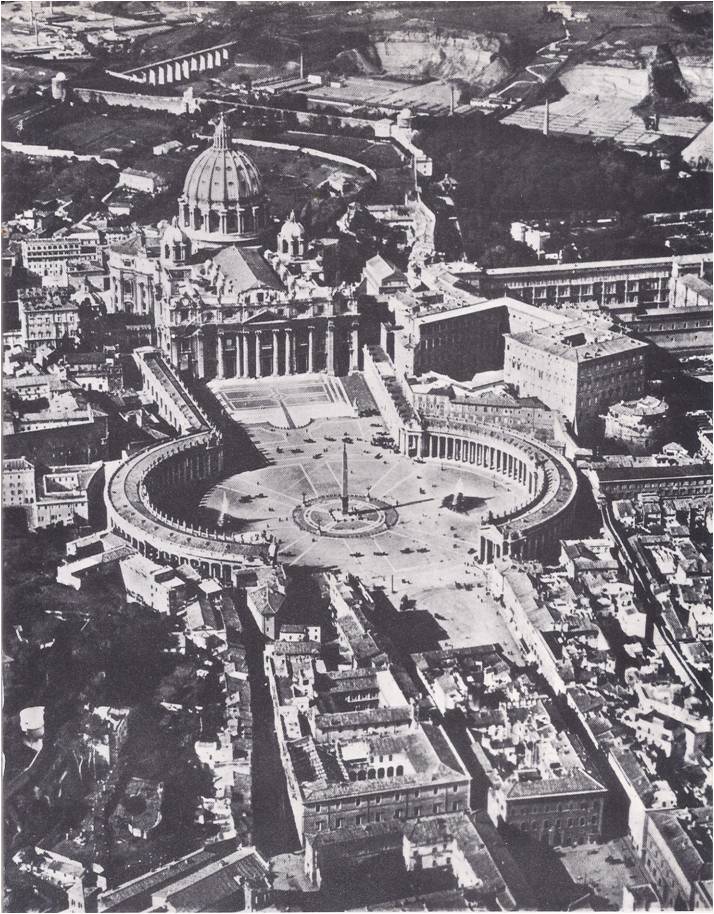

THE BLAST OF MUSKETS and the clang of swords against armour echoed across the plains of Italy, Spain and the Lowlands. Warriors of the king of France were clashing with the Spanish infantry and German knights of the Holy Roman Emperor. Control of the nations of Europe was the prize both nations sought. They schemed and plotted; their generals planned campaigns; their soldiers marched out to victory or defeat. Victories counted for little, for much of Europe’s future was decided by another, different kind of war – a war for the minds and souls of men. Village squares and royal council chambers, churches, university lecture halls and schoolrooms were the battlefields of this new war. Its troops were armies of preachers whose battle-songs were hymns and whose weapons were Bibles and textbooks. Reformers were on the march, Lutherans and Calvinists. Their thundering voices shook the domes of ancient cathedrals and wakened bishops dozing in their palaces. The Reformers won no easy victories‚ however. The forces of the pope were also on the march and the strongholds of the Church were well defended. Frightened by rebellions in Germany and Switzerland, the Catholic leaders in Rome took further measures to strengthen the Church. “There is but one way to silence the Protestants’ complaints‚” a learned churchman told the pope “and that is not to deserve them.” Lowly monks and the powerful cardinals alike began to talk of reform, of hard work, of honesty and godliness. Gradually there were deeds to match the talk — a great Church house-cleaning that one day would be called the Counter-Reformation. Meanwhile, in Europe’s towns and colleges‚ new soldiers of the Church appeared. Their uniforms were the simple black robes of monks, but their minds were as keen as dueling swords — much too sharp and smooth, …

Read More »