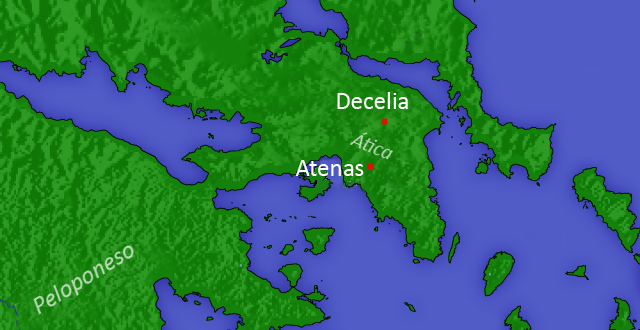

Socrates’ death occurred in the year 399 an Athenian court condemned Socrates for opposing the official religion of the state, a practice which in fact he studiously avoided and for “corrupting the youth”, which simply meant that he tried to get young people to think things out instead of yapping slogans. When the penalty was being discussed, Socrates said that, far from being punished, he thought he ought to be given free dinners for life in return for his services to the state. This independent line did not incline the court towards leniency and they were not interested when Socrates then offered to pay a fine. They condemned him to death. Socrates’ death by execution was dignified. Socrates was handed a cup of hemlock. He put it to his lips without trembling. He was not afraid of death, though he did not know what it might have in store for him. True to his often repeated maxim that our only certain knowledge is the knowledge of our own ignorance, he kept an open mind to the end. “Whether life or death is better, is known to God and to God only”, he said. “Thus died the man, who of all with whom we were acquainted was in death the noblest, in life the wisest and most just.” Those two quotations are from Plato (the first from the Apology, the second from the Phaedo).

Read More »