OF ALL THE RULERS OF EUROPE, none was more eager to please the pope, more anxious to prove himself a loyal son of the Church, than Henry VIII, the handsome young monarch of England. Henry was one of the first to offer his soldiers when the pope formed a Holy League to fight the Turks (and to frighten off the French kings, who had developed the unfortunate habit of invading Italy every few years). Henry never actually sent the troops. To show that he meant well, he wrote a strongly worded book about the duties that men owed the pope and the treachery of Lutherans who dated to question the leader of the Church. “What serpent so villainous,” he wrote, “as he who calls the pope’s authority tyrannous?” It was a most impressive and learned book and no wonder. Much of it was the work of Henry’s scholarly friend Thomas More. When it was published in 1521, the pope rewarded the king by giving him the title “Defender of the Faith.”

Henry was delighted with his new title, though not surprised. After all, he was used to being the best at everything he did. He wrote music which the palace musicians insisted was exactly the thing to play at court. He amazed his poets with the excellence of his verses, danced more skillfully than the most light-footed of his courtiers, killed more deer and wild beats than the best of his huntsmen and thought deeper thoughts than the philosophers in his universities — or so his courtiers said. It did not occur to him that people praised him merely because he was the king. Indeed, his one problem was to make use of his many talents when it took so much time to rule his kingdom. He did the best he could, hurrying from one project to the next according to his mood.

ANNE BOLEYN

Unfortunately, the Defender of the Faith seemed to look on women in the same way that he looked on his talents — he saw no need to stay with one when there were so many to choose from. Henry had a temper that matched his red hair. These two failings, added to his love of power, eventually led to trouble with the pope whose authority he had defended. Henry’s book was less than ten years old when he himself furiously denounced the tyranny of the leader of the Church. A few years later, he flatly denied that the pope had any power over Englishmen at all. England joined the Reformation, not for the sake of religious reforms (though the reforms were needed) and not because of Martin Luther’s books (though many Englishmen approved of them), but because King Henry was determined to have his own way.

The trouble began in 1526, when a young woman of the court introduced the king to her sister, Anne Boleyn. Henry had always liked pretty women, but Anne, with her pale skin and sparkling black eyes, enchanted him. He gave her a cordial welcome to the court and fell hopelessly in love with her. He wrote little songs and verses for her and begged her to come to live at the palace. Anne refused. She could not, she said, accept any favours from the king unless, of course, they were married. Henry was forced to agree. The marriage would be arranged, he promised, and soon.

HENRY ASKS AN ANNULMENT

The court was startled by this move and no one was more surprised than Queen Catherine, Henry’s wife. Their marriage, she knew, had been more a matter of diplomacy than love — she was a Spanish princess and her nephew was the Emperor Charles V. She was plump, pious and rather quiet, while Henry was dashing and fond of gaiety. For eighteen years they had managed to get along and Catherine had certainly not expected to be cast off for the sake of a little lady-in-waiting in her own court. In fact, she had not expected any changes at all, for the Church had strict rules forbidding divorce. Henry could look at as many pretty women as he liked, but he could have only one queen, Catherine, his lawful wife — and so the queen pointed out when he told her of his plans to remarry.

Henry had expected her to object and had answers for all her arguments. First of all, he was not thinking of his own good, but of the good of England. The kingdom needed a prince, a proper heir to the throne. Instead, there was the little Princess Mary, the only one of Catherine’s children who had not died. If Catherine could not give him sons, then it was plainly his responsibility to marry a woman who could. As for the Church, its laws could not, of course, be broken but, to please a man of influence and wealth, they could be bent. The pope had power to grant an annulment, a ruling that a marriage had not been legal in the first place.

Henry reminded his wife that their own marriage had not been strictly according to the rules. The Church said that a man must not marry his brother’s widow, yet Catherine had been the widow of Henry’s younger brother. True, Pope Julius II had found it possible to make an exception to the rule in order that Catherine and Henry could marry. Plainly the pope had made a mistake and heaven had proved his mistake by denying the King of England a son. Now was the time, Henry said, for the new pope, Clement VII, to undo what the old pope had done. He could correct his mistake by ruling that Henry and Catherine had never really been married at all and allow Henry to wed Anne Boleyn.

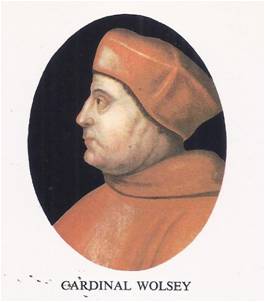

It was a neat piece of reasoning, so logical King Henry believed it himself. He called for his lord chancellor, Cardinal Wolsey and commanded him to explain the matter to Pope Clement. When the cardinal hesitated, Henry reminded him that the pope had recently granted a similar favour to the king of France. The cardinal agreed to write to Rome and Henry eagerly waited for a reply, certain that all would go well.

Queen Catherine also sent messages to Italy. They were tearful, angry messages to her nephew, the Emperor Charles V, who had just settled a quarrel with Pope Clement by conquering Italy and sacking Rome. Since the pope was almost his prisoner, Charles had little difficulty persuading him to think twice about Henry’s annulment.

For poor, worried Clement, a pope who had always had trouble making up his mind, this was a hopeless situation. He did not dare to cross the emperor. On the other hand, he did not wish to offend Henry VIII, whose kingdom was an important Catholic stronghold at a time when so many northern princes were joining the reformers. Finally he saw a way out. He appointed a committee to study the problem and told them to take their time about coming to a conclusion.

Months passed, and then years and nothing was done. King Henry hounded Cardinal Wolsey, the one English member of the pope’s committee. Wolsey could do nothing more than send pleading letters to the pope and Henry began to look about for other, more useful advisers. Thomas Cromwell, Wolsey’s secretary, seemed a clever and obliging man — rather sly, perhaps, but eager to please the king. Cromwell’s friend, Thomas Cranmer, an ambitious young churchman, also won Henry’s favour. When the archbishop of Canterbury died, the king suggested that Pope Clement appoint young Cranmer to the post. Though Cranmer was said to be something of a Protestant, the pope agreed to the appointment. By now, he would have done almost anything to please Englands’ king, except of course the one thing Henry wanted most.

When new demands for the annulment came from England, Clement found a new way to put things off. He dismissed the committee and announced that he himself would make the decision. He needed time to think. Henry was furious. He stripped Cardinal Wolsey of his titles, property and honours and in his place chose Archbishop Cranmer as head of the Church in England. Henry warned that he wanted action. If he could not deal with the pope, he would do without him. To show that he meant what he said, he prepared an order for the arrest of Cardinal Wolsey as a traitor.

The cardinal escaped punishment. Sickened by worry and disgrace, he died before the king’s order was signed. Cranmer, alive and hoping to remain so, made haste to do the king’s bidding. He had not been eager to become an archbishop, for he was indeed something of a Protestant. While on a royal mission to Germany, he had been converted to at least one of Luther’s theories — he had taken a wife. In England, as in all countries which kept the rules of the Catholic Church, a man could not be married and a churchman, certainly not an archbishop. England belonged to Henry VIII and when Henry VIII commanded, Cranmer had come home from Germany, hidden his wife and been crowned archbishop of Canterbury. Now, at the king’s command, he began to plan a campaign against the inconvenient rules that Henry had come to call “papal tyranny.”

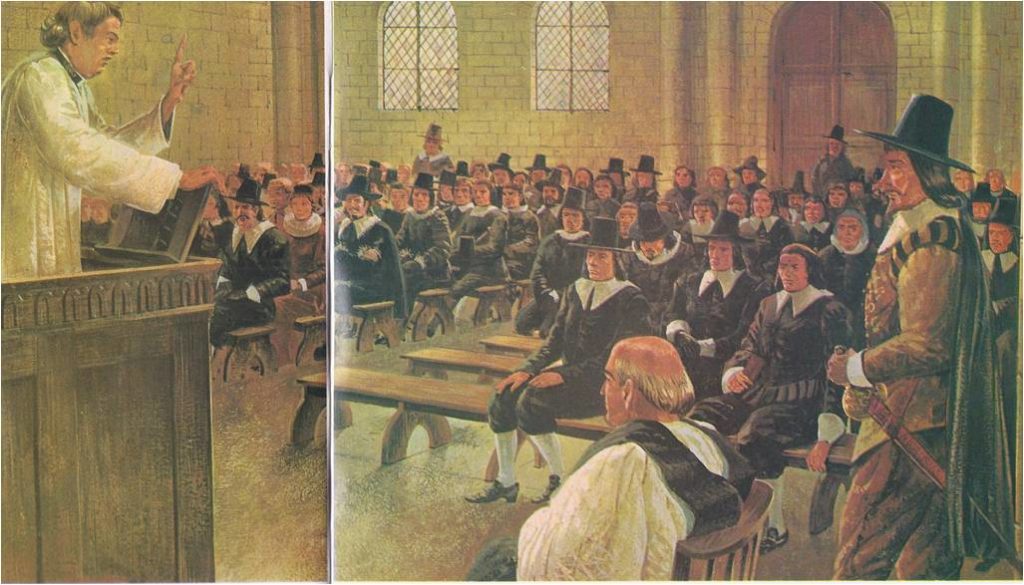

The king and his archbishop had no trouble winning the cooperation of the merchants, squires and traders who filled the House of Commons in Englands Parliament. Like the burghers of Germany and the Netherlands, these men were tired of handing over hard-earned gold to the churchmen from Rome. They envied the well-filled treasuries and tracts of rich land that belonged to Catholic monasteries in England and they listened with great interest to the tales of reforming princes and noblemen of Germany who had claimed the wealth of the churches and monasteries.

Whatever the English thought of Luther’s religious theories, they agreed that a little reformation could be good business. In 1532, the House of Commons passed an act abolishing all payments to Rome. Two years later, another act gave to the king all the rights that once had belonged to the pope. Then came the Act of Supremacy, which declared that the king was the one supreme head of the Church of England. All English churchmen were ordered to sign the act or stand trial as traitors.

“This Act of Supremacy,” wrote an ambassador, “is no less than declaring the king to be the pope of England.” Most of the priests and bishops supported the act, but a few did not. Among them was Sir Thomas More, chancellor of England, the man who had helped Henry write the book that won him the title of Defender of the Faith. More was Henry’s friend and a wise statesman, learned and well-loved at court, but he refused to change his religious beliefs. Henry ordered him beheaded and Thomas Cromwell was appointed chancellor in his place.

MANY NEW LAWS

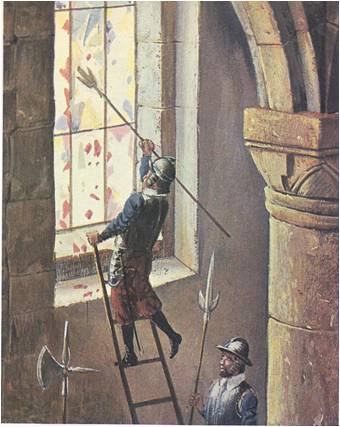

In Rome, the pope issued a bull of excommunication, declaring that King Henry and all his subjects were no longer members of the Church, no longer safe from the tortures of hell. Henry replied that he did not care if the pope issued ten thousand excommunications. He ordered his new chancellor to rid England of all reminders of papal tyranny, to close down the monasteries and to claim the church property for the crown.

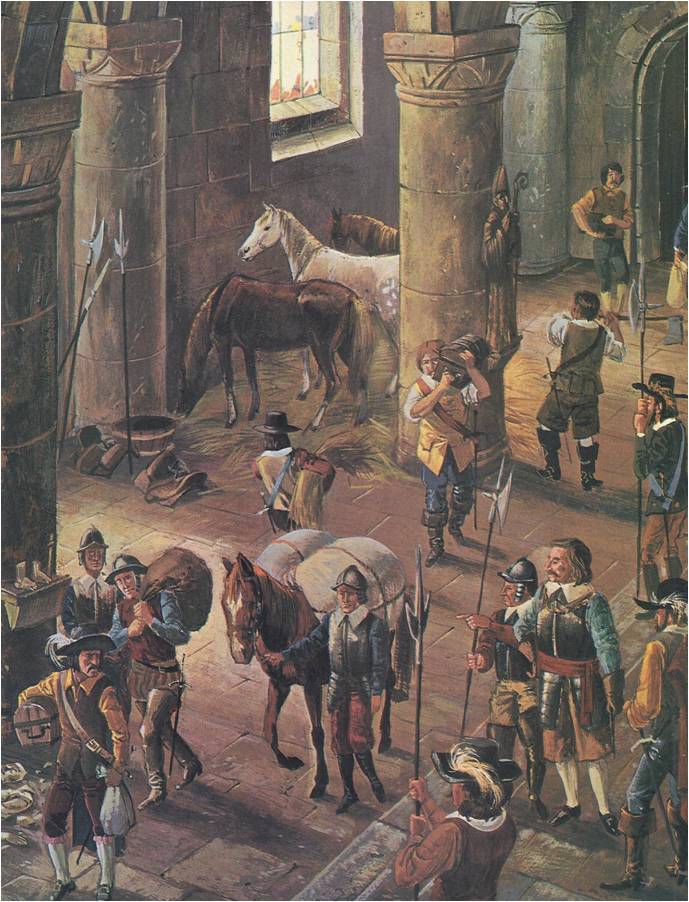

Cromwell went about his job with zeal. Indeed, he sometimes went too far, for he had decided that believing in reform was useful politically. To show his scorn for the old religion, he had his troops haul down statues of saints and popes, drag relics out of churches and stable their horses in cathedrals. His collections from the monasteries added more than 100,000 pounds a year to the royal treasury and provided fortunes, palaces and acres of fine land for Henry’s friends in Parliament. Henry was well pleased.

Many of Henry’s subjects were confused by the sudden changes and frightened of the pope’s anger. From the north, a throng of peasant farmers and craftsmen marched to London on a Pilgrimage of Grace to beg the king to seek the pardon of the pope. Henry’s troops sent them home, but no force of soldiers could convince the worried Englishmen that the king was right. “Masters, take heed,” one daring friar warned his congregation, “we have nowadays many new laws. I trow we shall have a new God shortly.”

It was a new queen, however, that Henry had sought and now she was his. Archbishop Cranmer had declared that the king’s first marriage was no marriage at all. The unwanted Queen Catherine and her daughter Mary had been sent off to lonely country castles where Spanish agents could not visit them and concoct plots. Henry’s new marriage had been properly celebrated and on a Sunday in 1535, Anne Boleyn had been crowned queen of England.

Three years later, Anne was beheaded. She had been unfaithful to the king, her judges said, and perhaps it was so. What was certain was that she had given her husband a daughter, Elizabeth, instead of a son and once again Henry began to find it impossible to think about one woman at a time. When Anne was gone, the king married Jane Seymour, a frail, pretty girl who gave birth to a son and died. Next came Anne of Cleves, a European noblewoman specially chosen by Chancellor Cromwell. Henry was delighted with the portrait of Anne that Cromwell showed him. When her ship decked at Greenwich and he went to meet her, his courtiers said that he “showed in his face that he was disappointed.” His first words to Cromwell were, “What remedy?”

Cromwell had no remedy. Henry did — he and Anne agreed that they would only be friends. She retired to a pleasant house in the country, while he married Catherine Howard, a charming English girl who had caught his eye. Cromwell was beheaded.

“Cromwell gone,” London’s gossips whispered, “and Cranmer will be next.” Gamblers laid bets on the number of weeks the archbishop had left to live. Cranmer himself was so concerned that he hid his wife overseas instead of in his place and thought of joining her in exile.

There was no place in England now for men with Protestant ideas. Henry had turned his back on the pope, but he was not, he insisted, a heretic. He had called for strong laws that required his subjects to follow nearly all of the old Catholic doctrines, customs, and punished harshly those who preached reform. Many of England’s Lutherans and Calvinists fled to Germany. Many others were executed. Cranmer — a prudent man, useful to the king, and more honest than most –stayed on and lived.

The new Queen Catherine was not so fortunate as Cranmer. In 1559, she moved into the palace, where the courtiers said, “she did nothing but dance and rejoice.” Two years later, she was led off to the Tower of London, condemned to death for being unfaithful to the king. Henry mourned her bitterly. He turned for comfort to a warm-hearted widow, Catherine Parr, who had been married nearly as many times as he had himself. In this Catherine the king met his match. If she was not as pretty as Anne or Jane, she did know how to handle men. She was, moreover, as clever and prudent as Cranmer — and like the archbishop, she lived to attend Henry’s funeral.

As the year 1547 began, Henry VIII was ill and seemed much older than his fifty-six years. He died on January 28 and with his death came a time of confusion in England. There were to be eleven years of shifting power, of triumphs and defeats for Catholics and Protestants alike and of death for many believers in both ways of worship.

“BLOODY MARY”

Henry’s crown, but not his strength, was passed on to his son, Edward VI. Edward was not quite ten years old. For six years England was actually ruled by Edward’s uncle, the duke of Somerset, Protector of the King and then by a council of lords. Both duke and council did all they could to make the Church of England Protestant. Henry’s laws commanding his subjects to worship in the Catholic way were cancelled. English Lutherans and Calvinists hiding in Germany rushed home. Archbishop Cranmer announced that he had come to believe in Luther’s theories and many of Zwingli’s, too. He wrote a new Book of Common Prayer, a worship service in English for Englishmen. He began to take dinner in public with his wife. Many churchmen who shared his beliefs thanked heaven, Parliament and the duke of Somerset for laws that allowed such freedom.

Their thanks turned into moans when King Edeward died in 1553. The council plotted to name a Protestant noblewoman as queen of England, but the scheme failed. To the throne came Mary Tudor, daughter of Henry’s first unwanted queen. She was a friend of Spain, the pope and a good Catholic.

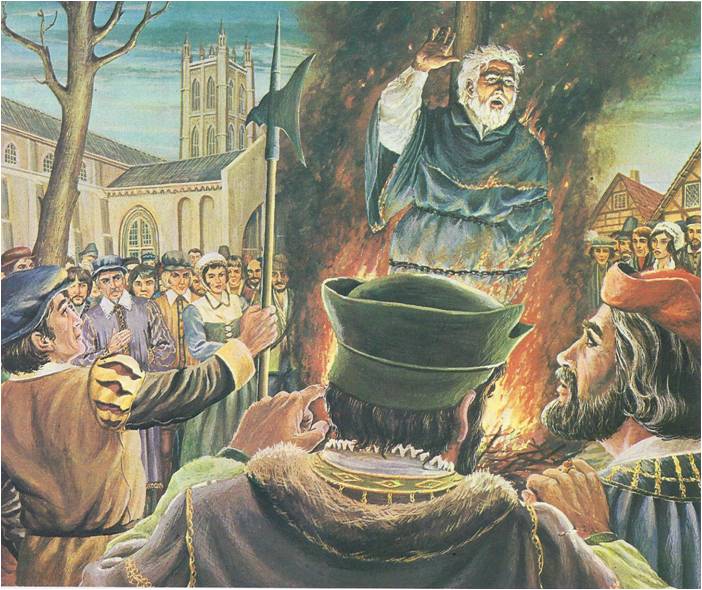

Once again, the laws were changed. The pope was acknowledged as leader of the Church. Protestant ways were banned, churchmen scurried to leave their wives or the country and Englands skies were lit by bonfires in which heretics were burned. In three and a half years nearly 300 persons, poor and rich, low and high, were burned. Among them were five bishops, who were burned together in the university town of Oxford while the scholars and townsmen watched shocked and silent.

Archbishop Cranmer was made a prisoner and commanded to give up all his Protestant beliefs. A pair of Spanish friars lectured and threatened him until at last he agreed that the Catholic Church was the only church and the pope its supreme head. He also signed a document saying that he had sinned as archbishop, particularly in approving Henry’s divorce. Condemned to die, Cranmer was set on a platform in a church at Oxford, preached at and told to pray. Kneeling, his face hidden from the throng‚ he prayed for a long time. Then he raised his head and spoke. He had given up none of his Protestant beliefs, he said; he had agreed with the friars only because he hoped, like a coward, to save his life. When he was dragged to the stake and the fire was kindled, he held into the flames his right hand, the hand that had signed the false document and betrayed his beliefs.

In the weeks after Cranmer’s death, an odd little song could often be heard in the streets of London. Carpenters sang it as they sawed and tailors as they sewed. Every alehouse hostess knew it and so did many noblemen:

Three blind mice, three blind mice,

See how they run, see how they run,

They all run after the farmer’s wife,

Who cut of their tails with the carving knife,

Did you ever see such a sight in your life

As the three blind mice?

The little song hid a serious meaning. The three mice were the bishops burned at Oxford. The farmer’s wife was Mary the queen — they called her “Bloody Mary” now. The farmer was Mary’s Spanish husband, King Philip II, whom she had married despite the complaints of Parliament. Englishmen singing the little song were angry and frightened. They wanted no Spanish king to rule them and they were learning to hate the religion of the queen. They distrusted the Jesuits who came to preach in English churches and teach in English schools. Most of all, they were suspicious of the representatives who came to Mary’s court from the pope at Rome; the queen seemed too willing to follow their advice.

Whatever a man believed in church, the English said, England should be English and bow to no foreigner. In city and village, men muttered against the queen. Those who dared not say what they thought sang the song of the three mice. Everyone prayed that Mary would die childless so that England’s throne would never fall to a ruler half-Spanish by birth and all Roman by religion.

QUEEN ELIZABETH

The prayers were answered. When Mary died, in the fifth year of her reign, she had had no children. The new ruler of England was Henry’s second daughter, Elizabeth, the child of Anne Boleyn.

Elizabeth was only twenty-five. Her people were poor and weary after years or religious strife, she was condemned by the pope and her country was threatened with war by the king of Spain. She had her father’s temper as well as his red hair, she had his skill in managing Parliament, the noblemen and she knew better than he how to win the love of the people of England. Merchants and craftsmen, farmers, soldiers and country squires rallied around her. If she had her faults, they said, at least she was thoroughly English. During Elizabeth’s long reign — more than forty years — England triumphed over Spain, England’s traders prospered as never before and the ways of the Church of England were settled for centuries to come.

Elizabeth’s solution for the problems of the Church was as English as she was herself. When she came to the throne, her people were divided. Some wanted the old ceremonies of their ancestors, some the new Lutheran ways and Cranmer’s Prayer Book. Elizabeth seemed determined to please them all. What she herself believed was difficult to tell. A Spanish ambassador spent a full afternoon trying to discover her true ideas on religion and gave up. “I can only say, my lord,” he wrote his king, “she is a woman and inconstant.”

Some English bishops agreed with the ambassador. When the pope had been told to mind his own affairs and Elizabeth named head of the church of England, she ordered the churchmen to use the English Prayer Book. At the same time, she ordered them to perform most of the old Roman ceremonies. This made a strange religious mixture — part Lutheran, part Calvinist and part Catholic. The new church — the Anglican Church as it was called — pleased the queen. It also pleased most of her people. To the surprise of other Europeans, the English found it comfortable to worship in a way both old and new.

CATHOLICS AND PURITANS

Some Catholics, of course, could not bring themselves to worship in the Anglican way, Elizabeth allowed them to go to Catholic mass as long as they did not claim that the pope had any power over them or England. This failed to satisfy a group of northern noblemen and they plotted to put Mary, the Catholic queen of Scotland, on the English throne. When the plot was discovered, Mary was lured to London, imprisoned and eventually executed. Elizabeth’s officers began to keep a closer watch on anyone who practiced the old religion. Then came the war with Spain and England’s Catholics quickly learned to hide their beliefs and their priests, for their neighbours looked upon them as traitors.

Things were even more difficult for the extreme Protestants. Followers of Calvin, they came to be called Puritans because they insisted that the church must be purified of all the old customs, ceremonies and decorations. They also refused to bow to the orders of bishops and archbishops, for Calvin had said that each local church should be run separately by the “elect” in its own congregation. When the Puritans broke away from the Church of England to go their separate ways, they won another new name — “separatists” — and the queen’s displeasure. Elizabeth had no patience with extreme ideas. She feared they would stir up disputes that had just been settled.

MANY CHURCHES

James I, the king who followed Elizabeth to the throne, treated the separatists more harshly still. To avoid punishment, they had to meet in secret, in private houses or shops or barns. Some of them left England altogether. They lived in Holland for a time, but they wanted their children to grow up like Englishmen, not Hollanders, so they turned to America, where they could build their towns and churches as they wished.

From Wittenberg and the garden with the pear tree, the ideas of Martin Luther had traveled far –across Europe, the English Channel and now the vast Atlantic Ocean. The changes they had brought about were equally great. The one church of Christendom had become many churches, each with its own ideas of religion, its own people seeking peace with God in their own way. The old Church that had once been the only Church had also changed. Gone were the indulgence-peddlers, the bishops who ruled only to win fortunes, the priests who spoke words they could not or did not explain. In their place were hard-working friars and missionaries, scholar-churchmen and priests who preached in order that their listeners might better understand their God.

In the first half of the sixteenth century, two revolutions took place in Western Europe. One was the Reformation, the start of the new religions called Protestant. The other was the Counter-Reformation, the rebuilding of the religion called Catholic.