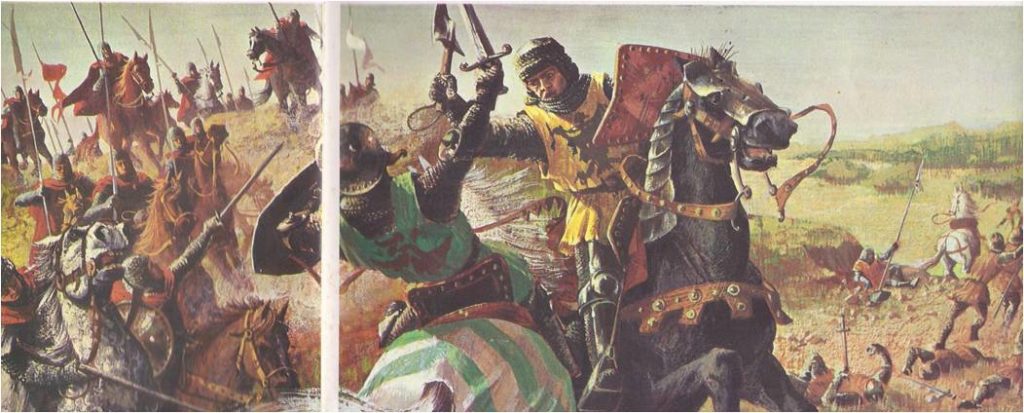

IN AUGUST of 1485, Henry Tudor landed on the Welsh coast to fight King Richard III for the crown of England. Henry was twenty-nine years old, lean and golden-haired, with a merry face. He was head of the Lancaster family, which had so far been defeated by King Richard’s family, York, in the Wars of the Roses. Henry was counting on help from many Englishmen and Welshmen who hated Richard. They believed Richard had hacked his way to the throne by murdering his nephews, they resented his taxes and rich living and they called him the “great hog” or “great boar.” Many Welshmen immediately joined the Lancaster chief, hopefully shouting, “King Henry! King Henry!” and “Down with the bragging white boar!” Henry marched north into England, gathering new followers. Richard mocked Henry’s troops as a few “faint hearted Frenchmen and beggarly Britons.” Even so, he raised a large army and advanced to Bosworth Field near Henry’s camp. When Richard roused his troops for battle on the morning of August 21, they stretched out, as a chronicler said, “a wonderful length,” so that the sight of the massed footmen and horsemen sent a thrill of horror through Henry’s camp.

On a knoll overlooking the countryside, Henry stirred his men to fight. He told them not to be dismayed by Richard’s large army. Painting to Richard’s camp, he said that there was a thief who had stolen the crown and now must surely fail. Against “yonder tyrant” his soldiers must advance “like true men against traitors . . . scourges of God against tyrants.” Then Henry led his men to the attack.

They marched with the archers in the centre and the foot soldiers on the right protected by a marshy bog. They advanced so that the sun was behind them and glared in the faces of Richard’s men. Once they were past the marsh, Richard’s archers loosed a hail of arrows at them and Richard’s cavalry attacked. Henry used his new weapon, artillery, but still Richard’s army came on. Henry’s men fought bravely, clustering around their standards and wielding their swords against the foe.

Sighting Henry at a distance with only a few men around him, Richard spurred his horse forward. He bowled over Henry’s standard bearer, crashed past one of Henry’s strong knights and engaged Henry man to man. The two rivals battled, gasping for breath. In the field around them, Richards army pressed on. Then one of Richard’s chiefs, Sir William Stanley, crossed to Henry’s side with three thousand men and turned the tide of the battle. Stanley’s men, their coats red as blood, fell on Richard and soon the cry went out that King Richard was dead. Many of his followers fled and the battle was quickly over. Stanley placed Richard’s gold crown on Henry’s head and again his soldiers shouted “King Henry! King Henry!”

Later, Henry was crowned King Henry VII at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London. A gold crown, as he himself had proved, did not make a safe kingdom. England was not really at peace. For the thirty long years of the Wars of the Roses the English nobles had shed each others’ blood, battered down castles, ridden over crops and disrupted trade. The Irish tribes had almost broken free of English rule. In the north of England, the barons ruled their men and castles almost like independent kings. They held court, kept thousands of armed retainers, feasted and hunted – and obeyed the king only when it pleased them. Farther south, robber-bands prowled the countryside, plundering where they could. “There is no country in the world where there are so many thieves and robbers as in England,” an Italian visitor wrote. The king was always in danger of losing his throne. Ireland and the north of England were Yorkist strongholds and there the barons and knights began sharpening their weapons for a reckoning.

Henry put his friends in command of strong castles that overlooked routes to the heart of the country. To make the Yorkists more friendly, he married Elizabeth, heiress of the York family. He founded strong councils to rule the north of England and Wales and he set up a great council for central England. As a further safeguard against disorder, he established the Court of the Star Chamber, a part of his council which sat as a high court.

The Star Chamber could arrest without a warrant and convict without a jury. To those who abused privileges, to those who loved the easygoing liberty of earlier times, the Star Chamber was a dreaded name. The ordinary citizens, however, especially the law-abiding ones, welcomed it. It frightened the great men who were used to treating justice as if they owned it and it protected the weak against the strong.

To sit on his councils, Henry favoured middle-class men. Ambitious for wealth and for the titles he might shower on them, they were completely loyal to him. The gentlemen farmers, merchants and lawyers of Henry’s Parliaments were also loyal, for to them Peace meant money. They wanted a strong king to stamp out thieves, tame the barons and revive trade.

Henry was suspicious of the great barons and he watched the young earl of Warwick with special care. Warwick was the Yorkist noble with the best claim in his family to the throne. The Yorkists in Ireland found a man who pretended to be Warwick and they invaded England.

Henry’s troops killed four thousand Yorkists and Henry scornfully put the false Warwick to work cleaning pots in the palace kitchen. He invited the Irish nobles to his palace, showed them the pretender serving food and said mockingly, “There is your king.” He forbade the Irish chiefs to hire armed soldiers, to carry guns without licenses, or even to shout their family war cries.

In Dublin, the Yorkists found another youth to imitate a Yorkist prince. His name was Perkin Warbeck and he was the son of a lowly French boatman. He was clever, graceful and the Yorkists taught him to speak English and to behave like a prince. They sent him abroad to seek money and soldiers. Warbeck found aid in France and Scotland and invaded England. Henry’s men easily scattered his weak little army. Warbeck hid in a wine cask, but Henry tracked him down, wrung a confession from him and paraded him through London. Henry had Warbeck and the real earl of Warwick put to death and with them died the Yorkist hopes of winning back the English crown.

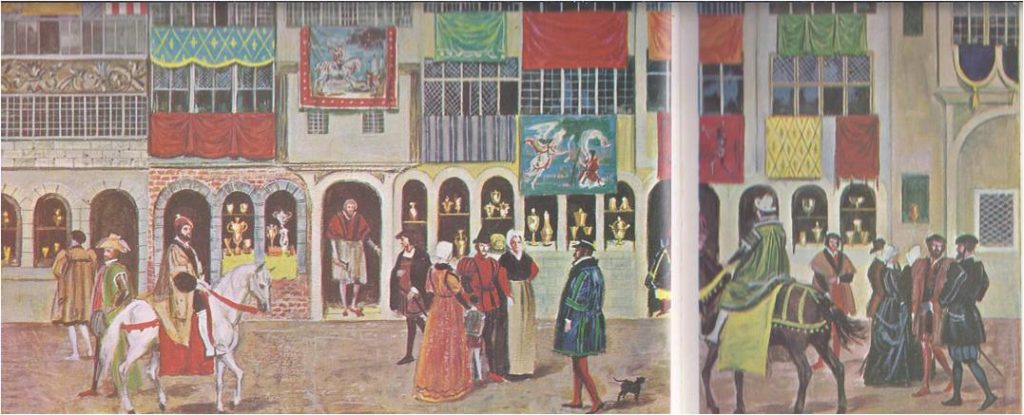

As Henry grew older, he changed; he became suspicious and cold. Once a man to be loved, he was now a king to be obeyed. Although he loved money and power and hoarded his own wealth, he also struggled to enrich England. He started trade wars with Venice and the German trading league, tracked down counterfeiters and protected English goods with favourable laws. Trade grew and London became a bustling city.

In one single street, the Strand, an Italia visitor found “fifty-two goldsmith shops, so rich and full of silver vessels” that they outshone the best shops of Venice and Milan. By the time Henry died in 1509, England was becoming a wealthy nation.

HENRY AND WOLSEY

The new king, Henry VIII, was a cherub-faced youth of eighteen. Learned and yet athletic, he had a great zest for life. He could shoot with any archer, ride with any huntsman and grapple with any wrestler. He loved music and wrote songs which he played on his own lute. Henry had hated his father’s miserly household and now he poured out his father’s carefully saved treasure on splendid clothes, great hunts, balls and feasts. He found it wonderful fun to act in court plays, disguised as a giant Russian, an Arab, or a wild man of the forest. His wife, Catherine, delighted to see him in his costumes and Henry was pleased for he loved Catherine well. He asked for her advice and let her influence him greatly‚ even to make war on the French, the enemies of her father, the king of Spain. The war was a failure for Henry and only helped Catherine’s father to conquer Navarre. European diplomats laughed at the young king’s folly.

Henry remained too busy with his own pleasures to use his power himself, although he was an able man. Gradually, however, he turned from Catherine to other advisers. He listened more and more to Thomas Wolsey, a humble but brilliant clerk whose father had been a butcher. Henry made Wolsey England’s chief minister and helped him become a Cardinal. The arrangement suited both of them. Wolsey ran the kingdom, while Henry hunted and played.

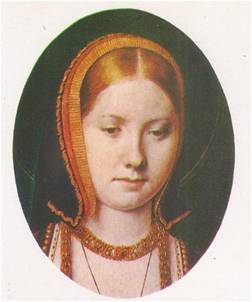

Catherine was older than Henry and as time went on he grew bored with her. Besides, Catherine did not bear him a son and he feared that Englishmen would not let his daughter Mary rule after him. Then he found a new love, a girl of his court named Anne Boleyn. Anne had a long neck, black hair and almond eyes and Henry thought her enchanting. He besieged her with letters and told her he loved her madly. Finally he swore he would divorce Catherine and marry Anne if she wished it. Anne needed no urging to agree to become queen of England.

Henry hesitated nervously for three weeks, then asked Catherine’s consent to the divorce. She broke down completely and wept. Henry babbled that perhaps things would work out and rushed away. He was still smarting with love for Anne and he had Wolsey write notes to Pope Clement VII, prodding him to grant Henry a divorce. Wolsey argued that Catherine had been first married to Henry’s older brother Arthur, who had died and that it was not legal for two brothers to have married the same woman.

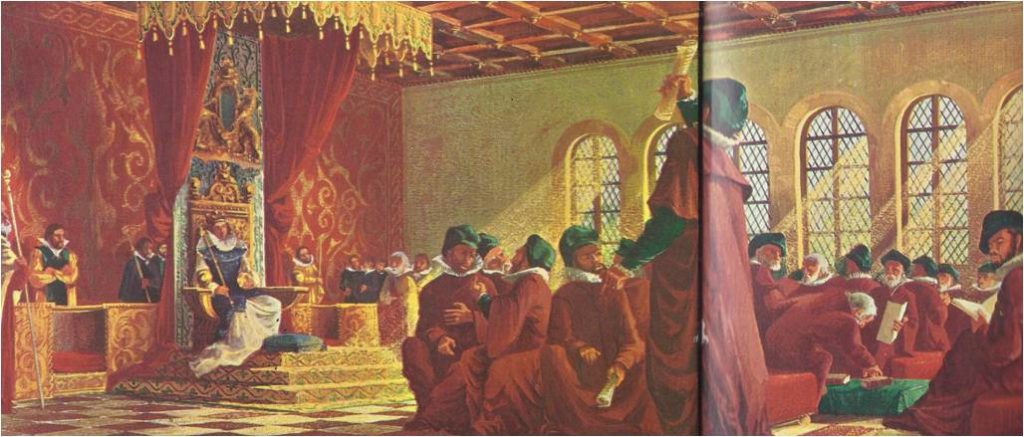

Pope Clement was in no position to act, for Italy was overrun with the troops of the Holy Roman Emperor, who was Catherine’s nephew. Clement feared that if he declared Catherine to be divorced, the emperor would burn Rome. Finally the pope sent Cardinal Campeggio to London as his emissary. To decide if the marriage was legal, Campeggio held a court trial in June, 1529.

“King Henry of England,” the crier called, “come into the court.”

“Here, my lords,” Henry replied.

“Catherine, Queen of England, come into the court.”

Catherine rose slowly from her chair, walked past the bishops, and knelt before her husband. “Sire,” she said in her foreign-sounding voice, “I beseech you for all the loves that hath been between us . . . take of me some pity and compassion. . . . This twenty years I have been your true wife or more and by me you have had diverse children, although it has pleased God to call them from this world . . . for the love of God who is the last judge . . . spare me the extremity of this new court.”

Henry remained silent during Catherine’s plea and the other listeners in the hall grew embarrassed. Catherine moved with slow dignity toward the exit of the great hall.

“Madam,” an usher cried, “you will be called again.”

She said sadly, “This is no impartial court for me,” and left.

Henry then reminded the court of his need for an heir, of the blood that might flow in a divided kingdom if he had no son. In Rome Pope Clement became alarmed again and called the cardinal away. Henry was furious and one of his supporters angrily said, “It was never merry in England when we had cardinals among us.”

Henry was hearing the same thing from other Englishmen. They told him that cardinals and popes were of no use to him. They spoke of Martin Luther, the German friar who had condemned the pope as “oppressed by Satan.” They reminded him of the rich church lands he could take if he broke with the Church of Rome. A young churchman named Cranmer, who looked like a rabbit and was very clever, made it clear that he was willing to give Henry his divorce.

Henry threatened to break with Rome, but still the pope did nothing and Henry decided to act. He dismissed Wolsey and ordered Catherine out of his palace. He made Thomas Cranmer Archbishop of Canterbury and Cranmer granted Henry the divorce; then Henry married Anne Boleyn. Rending the ties of centuries, Henry broke with the Church of Rome and created a separate Church of England with himself at its head. Henry had turned the challenge to his love and pride into a challenge of all Englishmen against the power of Rome.

Many Englishmen were made happy by Henry’s break with Rome. They resented the Church taxes that flowed to Rome and the good lands the Church held. When Henry seized the Church lands and sold them cheaply‚ they rushed to buy with no fear of the pope’s fury. There were also many loyal Catholics in England. When Henry closed down the monasteries the Catholics began a rebellion that spread wildly through all the unruly north.

Henry raged and he wrote to the rebels, “We marvel what madness is in your brain.” He was the king whom they were “bound by all laws to obey and serve.” The rebels, led by men of famous old families, gathered an army of thirty thousand men. Henry decided to trick them. He let them meet with his chief ministers in the north and he gave his ministers a pardon for them. Henry’s men showed the pardon to the rebel leader, Robert Aske and promised him that Parliament would discuss the rebels’ demands to worship like Catholics.

Tearing off his badge of revolt, Aske said, “I will wear no other badge than that of our sovereign lord.” When Aske and his men were separated and undefended, Henry had his soldiers ride them down and arrest them. Aske was hanged in chains at York; other leaders were burned to death or beheaded. Henry had wiped out the rebellion and now he established his Church in the north.

Henry also made himself head of the Irish Church, which he modeled on the Church of England. In the north of England, in Ireland and in Wales, Henry strengthened his government. In Wales he imposed English laws, making Wales part of England for the first time. His subjects were “bound to serve and obey,” he had said and now he welded England together under its own religion and his strong rule.

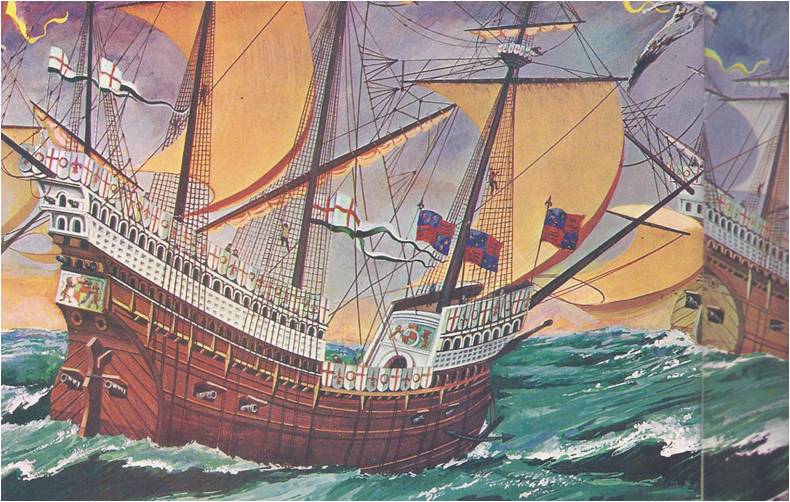

Henry still remained popular with most Englishmen. He strengthened English power as well as he enhanced his own and he founded English sea power. Early in his reign he launched the Great Harry, a giant ship of 1,000 tons, armed with thirty-four cannon and carrying 700 gunners, soldiers and sailors. He bought ships from the greatest naval powers of the day, the Venetians and the German Hanseatic League and he had books written describing the best tactics to beat the enemy at sea.

Up to this time, English ships were not heavily armed, but were fitted with a ram that splintered holes in the enemy’s hulls. Henry changed all this. He packed heavy guns in his ships and he placed them all along the ships’ length. Thus he originated the famous “broadside” that made sailing ships mightier than oar-driven galleys, which needed to keep their sides clear for oars. Henry’s broadsides were not really appreciated in his own day, but fifty years later they saved England from invasion.

Henry died in 1547, leaving his son Edward to rule England. The new king was a sickly boy only eleven years old. Since Edward was so young, his uncle, the Protector Somerset, ruled as regent. Somerset made England’s church more Protestant‚ forbidding such Catholic practices as the carrying of candles, the taking of ashes and the bearing of palms. Somerset also tried to deal kindly with a mass of poor roving beggars, who rebelled after they had been thrown off their land. Many nobles thought Somerset’s kindness was weakness and they were pleased when the ambitious duke of Northumberland overthrew Somerset and crushed the rebellion.

Northumberland had Somerset arrested, tried for treason and executed. Then he ruled England sternly in the interest of the great and wealthy. He made the religion even more Protestant. Services were now conducted in English, so simply that some thought them “like a Christmas game.” Well-known Catholics were arrested. Northumberland’s men even tried to arrest the Catholic chaplains of Mary, Henry VIII’s Catholic daughter, but Mary lashed at them with Tudor pride. “My father made the most part of you almost out of nothing,” she said, and soon she had her revenge.

Edward died before he reached his eighteenth year and Mary became queen. Since girlhood, Mary had suffered for her religion. She had been torn from her mother after Henry divorced Catherine. She had seen her father the king put a feather in his cap and dance merrily after he heard news of her mother’s death. When Mary refused to give up Catholicism or to agree that Henry and her mother had never been legally married, her father had threatened to knock her head against the wall “until it was as soft as a baked apple.” Mary had remained fervently Catholic and she was determined to make England Catholic again. She restored English ties with the pope and she married the leading Catholic ruler of Europe, Philip II of Spain.

Mary loved Philip wildly and said she would prefer death to having any other husband, but the English were becoming a proud nation; they hated the influence of Catholic Spain and many of them hated Catholicism. When one of Mary’s chaplains preached at St. Paul’s the audience cried “A Papist! A Papist! Tear him down! and one church goer threw a dagger at the chaplain. Another tossed a dead dog into Mary’s court, with a note saying that all priests should be hung.

BLOODY MARY

Mary revived the heresy laws, making it a crime to be Protestant. Englishmen who refused to become Catholic were burned at the stake; more than three hundred perished and their deaths earned the queen the name Bloody Mary. Edward’s bishops were hunted down and even the dead bodies of Henry’s and Edward’s churchmen were dug up and cast in the flames. Cranmer was browbeaten into making a confession of religious errors and then was burned. Fearing persecution‚ most Englishmen pretended to become loyal Catholics. Prosperous Englishmen had good reason to want to live. Trade was becoming more important in England than religion and even under Mary, English trade was growing.

Mary was angered by her younger half-sister, Elizabeth. When some Protestant rebels were caught a letter written by Elizabeth was found and Mary was sure Elizabeth had plotted with them. Mary sent Elizabeth to the dreaded Tower of London, but nothing could be proved against her and she was released. To win Mary over, Elizabeth pretended she was a good Catholic –attending a mass or two seemed a small price for staying alive. When Mary died in 1559, Elizabeth became queen.

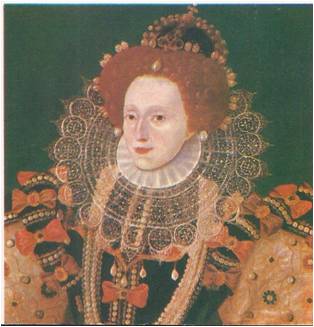

“A PLAIN ENGLISH GIRL”

When Elizabeth made her way to her coronation, one onlooker cried, “Remember old King Henry the Eighth!” Elizabeth quickly reminded the people that she was truly her father’s daughter. She contrasted herself with her half-Spanish sister Mary, noting that she, Elizabeth, was “a plain English girl.” A new mood swept England and later a historian wrote that Englishmen felt “the dashing showers of persecution overpast: it pleased God to send England a calm and quiet season, a clear and lovely sunshine . . . and a world of blessings by good Queen Elizabeth.”

Elizabeth knew religion was a touchy problem. In the north there were many strong Catholics, ready to fight for their beliefs to their death. In the south, hotheaded Protestants were impatient for revenge against Mary’s reign of blood. Elizabeth surrounded herself with capable advisers, chief of whom was William Cecil and she and her councillors worked out a new religion for England.

Dropping all of Mary’s changes, they brought back the worship of the first years of King Edward. This religion was fair and moderate and most Englishmen approved. Catholics, of course, were dismayed. Even so, Elizabeth did not punish Catholics who worshipped quietly in their own houses. She did not wish, she said, “to make a window in men’s souls.” When Catholic barons in the north rebelled, she punished them sternly.

The extreme Protestants, known as Puritans, also gave Elizabeth some uneasy moments. Puritan preachers called for an ideal Church which would be ruled by the people, not the queen. They loudly criticized the Elizabethan church, stirring up unrest. Elizabeth had her archbishop break up Puritan meetings and many Puritans were fined or arrested. Finally the Puritan leader was imprisoned by the Star Chamber and several Puritans were put to death. Only a few were executed and most Puritans were content to dream of their ideal church by night and remain loyal by day. For the time being, at least, they were Englishmen first and Puritan second.

Like most Englishmen, the Puritans supported Elizabeth in her struggle against her dead sisters husband, Philip of Spain. Philip was the mightiest monarch of the day, ruling much of Europe and most of the New World. At first, Elizabeth and Philip tried to be friendly; he even courted her and proposed marriage. Philip did not love Elizabeth, but he did love the Catholic Church. He hoped to control the young queen and through her to make England a Catholic nation again. Elizabeth laughingly refused him and the struggle between the two began.

Philip’s spies and agents hatched a daring plot. While the English Catholics rebelled, Spanish troops were to invade the land and Elizabeth was to be seized or murdered. Philip planned to put Mary Stuart, the Catholic Queen of Scots, on the English throne. William Cecil grew suspicious and found secret ciphers hidden beneath the tiles of a Catholic nobleman’s house. Cecil smashed the plot, the first of many that he would put down.

Elizabeth was as busy plotting as Philip. She gave men and money to help the Dutch Protestants revolt against Spain, seized a Spanish treasure fleet in the English Channel and sent Francis Drake to capture Spanish treasure in the New World. Drake became so feared by the Spanish that they called him “The Dragon” and said he was a sorcerer who used a magic minor to discover Spanish treasure ships. They thought he could order the sea winds to do his bidding and wreck Spanish ships against the rocks.

Mary Queen of Scots took part in the plots of Philip and other Catholics against Elizabeth, but for years Elizabeth hesitated to punish another queen. Emily, murmuring in Latin, “Suffer or strike, strike or be struck.” Elizabeth agreed to Parliament‘s demand that Mary be executed.

THE SPANISH ARMADA

Now there was no chance that a Catholic would succeed to the English throne and Philip decided to take England by force. He began building a mighty navy, but in April of 1587, before it was complete, Drake sailed into the bustling Spanish port of Cadiz with seven ships. Drake’s aim was “to singe the Spaniard’s beard” and discourage Philip’s invasion. Although his captains were afraid to follow him, Drake drove into the inner harbour. His broadsides smashed twelve of Philip’s best galleys to splinters. Drake then rifled and burned twenty-four merchant vessels and towed away six more ships as prizes.

Learning from his defeat, Philip built a more modern fleet of 130 ships, the largest navy ever to sail the open ocean. It was called the Invincible Armada and in the spring of 1588 Philip put the duke of Medina-Sidonia in command and launched it against England. Philip ordered masses said throughout Spain for its success and he himself fell to his knees to pray for victory. If the Armada succeeded in invading England, the Dutch revolt and all of European Protestantism would collapse at Philip’s feet.

Elizabeth realized how dangerous the Armada was and borrowed money to defend England. She brought together her thirty-four fighting ships, hired almost a hundred armed merchant vessels and engaged the sailors of Cornwall and Devon, who were skilled with ships and war. She made Charles Howard the admiral of her fleet and Drake the vice-admiral. She did not have enough money to pay for all her ships and Drake provided for his squadron out of his own pocket. Dishonest contractors and harried officials made difficulties‚ but Howard had the highest praise for “the gallantest company of captains, soldiers and mariners that I think were ever seen in England.”

Through a gray winter and spring the fleet waited impatiently and then the approaching Armada was sighted. When the news was brought to Drake, he was playing bowls. “We have time enough,” he said coolly, “to finish the game and beat the Spaniards, too.”

GALLEONS AND GALLEASSES

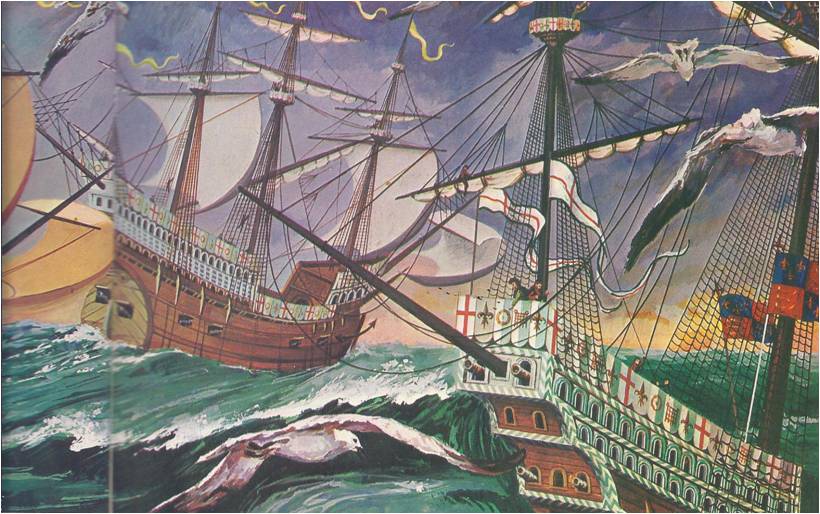

Drake and Howard were confident because of the drubbing Drake had given the Spanish galleys in Cadiz. When the English sailed out to do battle, they found no galleys. Instead‚ there were great galleons with tall castles. Their sails gleamed with painted emblems — giant crosses‚ portraits of saints, noblemen’s signets, crossed swords, falcons and jeweled designs — and pennants and flags fluttered from the masts. There were galleasses as well, ships English writers described as being of enormous size, with towers and turrets above and great halls and chapels below, where the Spaniards prayed for victory.

The galleasses were actually the same size as the galleons‚ but they were very heavily armed. They had gun turrets on platforms above the oarsmen and their cannon shot heavier balls than did any of the English guns. The English could shoot farther, but when they attacked they found their lighter balls left the thick Spanish hulls unharmed, for four days the Spaniards fought off their rivals and sailed nearer to England. It was a much stronger fleet‚ Admiral Howard wrote Elizabeth and her council, than they had expected.

VICTORY FOR ENGLAND

Elizabeth rallied her soldiers, who waited on land to defend England’s shares. “Let tyrants fear,” she said. “I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the hearts of my subjects. I am come amongst you all to lay down for my God and for my kingdom and for my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust.”

The land battle never came. Shortly before mid-night on July 28, Howard and Drake set fire to eight small ships and sent them sailing into the midst of the Spanish fleet. Sidonia‚ panicking, ordered the Spanish anchor lines cut. In the confusion, one of the galleons lost its rudder and another ran aground. By the time dawn broke, the Spanish fleet had been scattered out of its tight formation.

The English saw that this was their chance and pursued the enemy. Sweeping ahead, Drake’s Revenge poured a broadside at close range into the powerful San Martin, then wheeled into the wheeled into the wind and fired again. The English guns blazed away and the slaughter of Spanish soldiers and sailors made some of the upper decks slippery with blood. Even so, the lighter English shots could not blast through the thick Spanish hulls.

The English suffered some damage — Drake’s cabin was twice pierced by cannon balls — but then the Spaniards began to run out of round shot. The English closed range, hammering away at the Spanish hulls until many were riddled and ready to sink. Keeping to the wind, the English forced the Spanish ships east toward the dangerous shoals of the Flemish coast. The fight raged until after ten at night, with cannon fire and blazing ships lighting up the darkness.

The sea rose higher, the wind became a gale and by dawn the Spanish were almost upon the shoals. Sidonia and his men expected the English to close range and finish their night’s work. “We are lost,” Sidonia called to one of his captains and he thought, “God alone can rescue us.” A Spanish bodyguard later wrote, “It was the most fearful day in the world, for the whole company had abandoned hope of victory . . . looked only for death.”

The English were almost out of shot themselves and at almost the last moment the wind shifted and the Spanish fleet wallowed away from the shoals. The crippled remains of the fleet fled north, leaking, desperate, short of food and water. Wind and storms drove many of the Spanish galleons onto the Irish coast, where the finest of Spain’s soldiers were butchered by English soldiers and Irishmen.

In England church bells chimed out at the news of victory and Elizabeth declared a holiday. Singing and bonfires celebrated the triumph and a medal was struck to mark the victory which had saved England, her queen, and her religion.

Elizabeth led Englishmen in peace as she had in war. She helped England grow wealthy, establishing a sound coinage and chartering companies to trade with distant lands. These companies sent their ships to Greenland, the Levant and the East Indies, their voyages laid the foundations of a great empire. Their wealth helped Englishmen build new towns and start new industries. The great nobles also added to the growing wealth. Burying their old feuds, they bought shares in the new companies and improved their own lands, draining swamps, planting new crops and building their fortunes.

Nobles, merchants and gentlemen farmers and their lawyer sons took a new interest in English politics. They competed for election to Parliament and there they often raised their voices in criticism of the queen. They wanted a greater say in the affairs of their growing nation, just as the Puritans in Parliament wanted more of a share in church affairs. Parliament members grew unruly and sometimes when the Queen’s councillors asked them for money they laughed and complained. Yet, using all her Skill, the old queen was still able to unite Englishmen behind her, to pass the laws she wanted and to remind her people of the proud nation the Tudor rulers had given them.

KINGS AGAINST NOBLES

The Tudors of England were not unusual as strong rulers. All over Europe, kings were struggling to batter down the power of local lords and to create one strong government in the country, the government of the king. The king’s courts, the king’s army, the king’s laws began to rule the lands. Nowhere did the nobles give in willingly and sometimes they crippled the king’s power.

The struggle of king against nobles was also a struggle to create a single people, proud of their national history, their national language and their national strength, rather than a people who were the weak and divided followers of local lords. Where a king was successful, a nation arose, uniting the separate dukedoms, baronies and principalities. Where the king failed, the country remained week, divided and was often ruled over, stamped upon, fought for and humiliated by foreign kings.

Sometimes religion split a country and prevented its king from building a nation and sometimes a king used religion to unite a people, making all worship a single religion, or burning or exiling from his land those who refused. Some kings were so successful at crushing the nobles, breaking up parliaments and putting religious leaders and generals and ministers of state under their thumbs that they ruled like dictators. Then their power seemed “absolute” and they were known as absolute rulers.

DIVINE RIGHT AND ABSOLUTISM

To explain why a king’s power should be so great, philosophers and scholars came up with new theories or adapted old ones. Some wrote that the king ruled by divine right, that is, by the will of God. Others said that the king must have absolute power if his country were to enjoy peace, order, and prosperity. In unifying their countries, in strengthening and ensuring their own power, most of the strong kings did make their lands more peaceful, prosperous and greater than they had been before.

In theory the rule of the kings was “absolute,” the age of these strong kings is sometimes called the Age of Absolutism. Although their power was very great indeed, they were often not really so absolute as they seemed to be. For no matter how complete, how absolute, their power might be in theory, many of the kings found that in practice they had to pay some attention to the needs and desires of their subjects. Kings who forgot this often found themselves faced with discontented subjects and even with rebellion.

The Tudors in England ruled strongly‚ but they were not absolute rulers and absolutism did not appear there for some time. The rulers and the people generally worked well together for their own glory and Englands. Parliament’s strength grew along with the king’s, commerce flourished, the people prospered, became patriotic and liberty-minded Englishmen. Elsewhere in Europe the story was different. The struggle of kings against nobles, the struggle for nationhood and power, lasted for decades or even centuries.