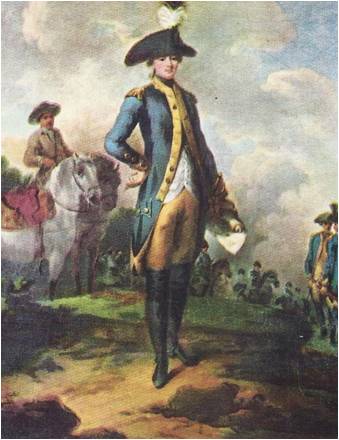

WHEN THE MARQUIS DE LAFAYETTE returned to France in 1782, after taking part in the American Revolution, he was hailed as a popular hero. It was pleasant to be welcomed as a champion of liberty, but he had been in America so long that he was beginning to see his own country as an American might see it and he was troubled. France was one of the largest and richest countries in Europe and yet the wealth of the nation was in the hands of a few, while the great majority of the people had almost nothing. He found a disturbing emptiness in the faces of the people. On country roads, peasants often stared at him with hollow eyes and blank faces. They seemed to have so little to live for. The nobles and the rich had discovered ways of avoiding taxes and the entire tax burden fell on the poor, who scarcely had enough for themselves and their families.

These were the people who now turned to Lafayette, hoping that he might lead them in their fight for liberty. Lafayette was eager to help them. “When one loves liberty,” he explained, “one is not at peace until after having established it in one’s own country.” He and thousands of other Frenchmen believed the people of France could win liberty for themselves if they followed the example set for them by the Americans. Many had read Thomas Paine’s famous pamphlet Common Sense, which had stirred the Americans in their fight for liberty. Many had also studied the rights of man listed in the Declaration of Independence. Writers pointed out in newspapers and books that these rights belonged to all men everywhere and that they had always been denied to ordinary Frenchmen. The French had been cheered by the American victory and hoped that they, too, could somehow win liberty for themselves. There were great differences between the two countries — differences which made it impossible for the American Revolution to serve as an exact model for France.

The American ideas about liberty had been developed and tested by the colonists for a hundred and fifty years before the revolt against England. During that time they had established a free society and had learned how to govern themselves through elected representatives. To them, liberty was as real as sunshine and rain. The American Revolution therefore, was a fight to protect a way of life which the British king was threatening to destroy.

Liberty in France, on the other hand, was little more than a hope. It was something people read about and talked about and wanted to experience. Power had always been in the hands of kings and nobles. The ordinary people of France, some ninety-six per cent of the total population, had no voice in the government. So, before there could be liberty in France, there would have to be sweeping changes in government and society. The French would have to wipe out class differences, uprooting a way of life which had been in existence for many centuries. Yet, the liberal leaders of France seemed to believe that all this could be accomplished in an orderly manner without bloodshed. Most of these leaders were against violence. They knew, of course, that no important changes could be brought about peacefully without the consent of the king. They felt he would not stand in the way of these changes for long because the public demands for them were becoming louder and louder.

THE RIGHTS OF MAN

It was not necessary for the liberal leaders to point out the evils of the French system of government. That had been done time and again, over a period of at least sixty years, by Voltaire‚ Montesquieu, Rousseau and other famous writers. These men had led the French out of the age of ignorance and superstition into a new age of reason where people were better informed and dared to think for themselves.

Although these writers had not agreed on many things, most of them admired the British system of government, its law-making Parliament, its fine courts, its freedom of press, religion and held them up as examples for the French to follow. They had led the fight against the torture of prisoners, cruel punishments and the practice of treating all suspects as guilty until proven innocent. In general, they had encouraged people to think for themselves and to speak out against wrongful uses of power by the church and by the government.

Rousseau had been a champion of the rights of man. He agreed with the English writer John Locke that all people had the right to life, liberty and property. It was the duty of government, he said, to protect these natural rights of its citizens. He also believed that the government received its authority to govern from the consent of the people. Such ideas were well known and widely accepted in France long before the American Revolution. The American victory was taken as proof that these ideas were not only right, but practical as well and made the people more impatient than ever in their demands for better government. They were willing to follow anyone who would lead them to freedom.

LAFAYETTE AND FREEDOM

Yet there was little that Lafayette could do. He did use his influence to promote religious freedom, so that Protestants in France would no longer be treated unfairly. He also worked to outlaw the slave trade. He suggested that the king free his slaves in Guiana, a French possession in South America. Each of the newly freed slaves, he said, should be given a piece of land upon which he could earn his living. When the government showed no interest in his plan, Lafayette bought two plantations and forty-eight Negro slaves in Guiana. He arranged to give the slaves special training, intending to release them as soon as they could care for themselves. When he wrote George Washington about the plan, Washington replied it was striking proof “of the goodness of your heart . . . God grant that a like spirit may come to . . . all the people of this country!”

In 1784, Lafayette visited America, where he asked Washington’s advice on how to gain freedom for the French. Washington was unable to help him. He pointed out that the Americans were still trying to establish a representative form of government under which they could enjoy the freedom they had won. The states had still to form a union and write a constitution. On the subject of slavery, Washington said that he and Jefferson would support any plan that would free all the slaves in Virginia. There was danger in such a plan, he said, because many white people still refused to open their eyes to the truth that all Americans, regardless of color, had the right to enjoy liberty and equality as citizens. At the same time, Washington encouraged Lafayette to go on with his plan of freeing his slaves in French Guiana and gave him a large sum of money to help pay expenses.

Returning to France, Lafayette felt like a man with his hands tied. There were so many things that needed doing and so little that he could do by himself. He became restless. He often visited the new American ambassador, Thomas Jefferson and there he met other Frenchmen who thought as he did. They spent many hours together discussing the problems of France. The king, Louis XVI, meant well, but he was a weak man with little interest in the affairs of government. He was too easily influenced by his extravagant wife, the unpopular Marie Antoinette amongst others and surrounded himself with weak ministers. Most of the ministers remained in office only a few months and seemed more interested in retirement pensions for themselves than in government business.

Another problem that deeply troubled Lafayette — and all Frenchmen — was that of money. France was deeply in debt, partly because of the American Revolution. The government had borrowed such huge sums to aid the Americans that most of the taxes it collected had to be used just to pay interest on the loans. Each year the government was forced to borrow still more money to pay for the expenses of running the country. Now the national treasury was empty and it was almost impossible for France to get more loans.

Taxes had already been raised so high that it was impossible to raise them again. Furthermore, the taxes came from the people who could least afford it — the lower and middle classes. The nobles and the church were required to pay very little and rich businessmen could avoid paying in dishonest ways.

Due to the money problem, something happened that allowed Lafayette to take action at last Calonne‚ the king’s minister of the treasury, called an Assembly of Notables together to consider the tax question and other government problems. He chose the members of the assembly himself and among them was Lafayette. All the members were noblemen, but they represented the various regions of France and the Church as well.

When the Assembly of Notables met in February of 1787, Calonne presented an outline of his program. Although the assembly had no power to make laws‚ it could make recommendations to the king. Calonne hoped the approval of his program would influence the king to carry it out. He asked the assembly members to recommend changes in the law that would greatly increase their taxes and cut down on their privileges as noblemen. Most of them opposed it. Lafayette and other liberals opposed it for different reasons. They felt it did not go far enough.

Instead of discussing Calonne’s program, the members used the opportunity to find fault with him as a minister. Lafayette asked the assembly to recommend full rights of citizenship for Protestants, which it did. Later he spoke out against dishonesty in government and asked the king to call a meeting of an elected body of representatives from all classes, known as the Estates General. The members of the assembly were shocked at Lafayette’s boldness. The Estates General was something from the past; it had not been in existence for 175 years. Did Lafayette realize what he was saying? Why, it was like telling the king that the nobles no longer had confidence in him, that they wanted him to turn his law-making powers over to the representatives of the people.

While the assembly refused to act on Lafayette’s suggestion, the idea was immediately picked up by writers in newspapers and pamphlets. Everywhere in France, people began to demand that an Estates General be called to bring about the changes that France needed. Even the members of the assembly began to change their minds. Lafayette was delighted with the public’s support of his views. He mentioned it in a letter to Washington, saying that “the King and family . . . don’t forgive me for the liberties I have taken and the success it had among the other classes of people.”

THE KING TAXES THE NOBLES

Calonne became so unpopular with the assembly that the king dismissed him and appointed Brienne in his place. The new minister tried to work out a program which would please the nobles, but they refused to approve his tax plan. They said that, in fact, they had no authority to approve taxes and hinted that only the Estates General had the power to do so. The king dismissed the Assembly of Notables in May of 1787 and made new laws providing for certain changes and new taxes. These laws were sent to be registered by the high courts of appeal in the various provinces. All the king’s laws or decrees had to be registered in this way, so that the courts of the land would have a record of them and could enforce them. The high courts of appeal could make comments about the new laws; the king could act on them or not as he pleased.

Over the course of the years, these courts had tried to strengthen themselves by declaring that they were one body, representing all the people of France and that one of their duties was to protect the people from bad laws made by the king. When the king sent them a law they did not like, they simply refused to register it. These courts did not in fact represent the people. The judges were all nobles. They owned their judgeships and passed them down from father to son. Naturally, they were against any laws which would take power away from the courts, or would weaken the special privileges of the nobility. They were also very much against any laws that made the nobles pay their share of the taxes.

King Louis XVI’S new laws did indeed place a heavy tax burden on the nobility. The high court of appeals in Paris refused to register it, saying that only the chosen representatives of the people in the Estates General had the power to pass new tax laws. The king ordered the judges to register the laws. When they refused, he punished them by sending them into exile in another city. Then the high courts in the provinces protested. They refused to carry on their work so long as the judges were in exile. Since the new laws could not be enforced without the help of the courts, the king and his minister withdrew the new laws and allowed the exiled judges to return to Paris.

This left the money problems still unsolved and Etienne tried to meet government expenses by borrowing more money. But this, too, required the consent of the high court in Paris. That court would not consent to more borrowing, it said, unless the king promised to summon the Estates General. It took the position that the money problems of France could never be solved without the help of the Estates General, for only that body, representing all the people, had the power to make new tax laws. People of all classes strongly supported the court’s view and raised the cry: “No taxation without representation!”

The fight between the king and the courts went on for many months. Liberals stirred up the people in all parts of France and the public demand for the calling of the Estates General grew louder. Bankers refused to lend more money to the government and finally, when the national treasury was empty, the king gave up. He called the Estates General into session on May 1, 1789.

Louis’ struggle with the courts was really a struggle with the nobility, for the judges were all nobles and they were fighting to protect the special privileges of their class. This revolt of the nobles marked the beginning of the French Revolution.