DURING THE years that followed Hitler’s adventure in the Munich beer hall, ministers came and went in the German government. Among them were some able men, particularly Gustave Stresemann. He was foreign minister from 1923 until his death in 1929. His policy was to work out a way of getting along with Germany’s former enemies; so that Germany’s mighty industrial machine could operate again as it had in the past.

This policy brought results. Inflation was stopped and foreign bankers made large loans to German industry. Smoke poured from the smokestacks of Germany’s efficiently run factories and the republic began to prosper. It looked as though history had taken a new turn — a turn that would leave Hitler forgotten.

Then came 1929. A great depression had begun in Europe and the United States; Germany’s recovery was at an end. There were no more foreign loans for German industry and few markets for its goods. The wheels of factories stopped turning, thousands of people were thrown out of work and long breadlines stretched through the streets of the cities. The Germans had just begun to forget the terrible days of inflation and now they faced days that might be just as terrible, or even worse. The government seemed helpless and so they turned to the communists — and to Adolph Hitler and the Nazis.

Hitler was ready. He had his brown-shirted storm troopers and his black-shirted SS men — the Schutzstaffel, his specially picked and trusted soldiers and guards. To help carry out his orders he had fat Herman Goering, serious Ernst Roehm and meek-looking Heinrich Himmler. He also had Dr. Joseph Goebbels, a small, dark, well-educated man with a limp, who would prove to be a master of propaganda. For the people, Hitler had promises, all kinds of promises. He would give jobs to the jobless. He would bring back prosperity. He would refuse to abide by the terms of the Versailles Treaty. He would control the bankers and industrialists. He would build Germany into the greatest nation in the world. With his promises, he gave the Germans someone to blame for their troubles, someone to hate and despise — the Jews and the Marxists.

As the depression continued and the number of unemployed mounted to more than six million, Hitler began to get money. The men, who ran Germany’s great steel, chemical and coal companies, its banks and insurance companies, were afraid that the communists would take over the government. Hitler had promises for them, too, even though he had attacked them in his speeches. He would protect them from the communists; he would save them from a red revolution; he was the communists’ most bitter enemy. Industrialists, bankers and businessmen were impressed and they gave him millions of marks to support the activities of the Nazis.

With the money, Hitler was able to reach even more of the German people. The people listened. It made no difference to them that most of what Hitler said was lies. It made no difference to them that the Jews and the Marxists were not to blame for Germany’s troubles. It made no difference to them that Hitler promised something that sounded like socialism and meanwhile took money from bankers and industrialists. The people were hungry and fearful. They wanted a way out of the depression and Hitler seemed to know the way. So they listened, attending meetings that were becoming larger and larger. They raised their hands in the salute that Hitler had borrowed from Mussolini and shouted, “Heil Hitler!” — “Hail Hitler!”

There were weaknesses in the government, too, that made things easier for Hitler. It clamped down hard on the communists, but it allowed Hitler’s stormtroopers to do much as they pleased. There were also weaknesses in Hitler’s opposition. Both the Social Democrat party and the Communist party were opposed to him. If they had united their forces, they might have been able to win more votes in the elections than the Nazis, but they did not trust each other and they fought each other almost as much as they fought the Nazis.

Moreover, the Germans had no tradition of democracy. They had been taught to respect authority and obey orders without question. So they listened, believed and shouted, “Heil Hitler! Heil Hitler! Sieg Heil!”

They voted for Hitler. In almost every election held during the 1930’s, the Nazis made gains over the previous election. In 1932, Hitler ran for president against General Paul von Hindenburg, a German hero of World War I. Although the chancellor was the real power in the German government, he was appointed by the president, so that post, too, was important. Hitler lost the election. He now had about 400,000 stormtroopers and for a while he considered overthrowing the government by force. Then he decided against it. His brown-shirts had to be content with street fights against Communists and Social Democrats during the election campaigns for the Reichstag, the German parliament.

By 1932, the Nazis had won 230 seats in the Reichstag — the most any party had won since the beginning of the republic. Hitler demanded that he be made chancellor. The eighty-five-year-old President Hindenburg refused, instead appointing Franz von Papen. When von Papen saw that he could not get the support of a majority of Reichstag members, he called for a new election. This time the Nazis lost 2,000,000 votes and won only 37 per cent of the total vote, while the Communists gained. Even so, the Nazis had the largest number of seats in the Reichstag and again Hitler demanded that he be named chancellor. Again he was turned down, because he also demanded the powers of a dictator. General Kurt von Schleicher got the post, but he, too, could not win the support of the divided parties in the Reichstag. He resigned and at last Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor.

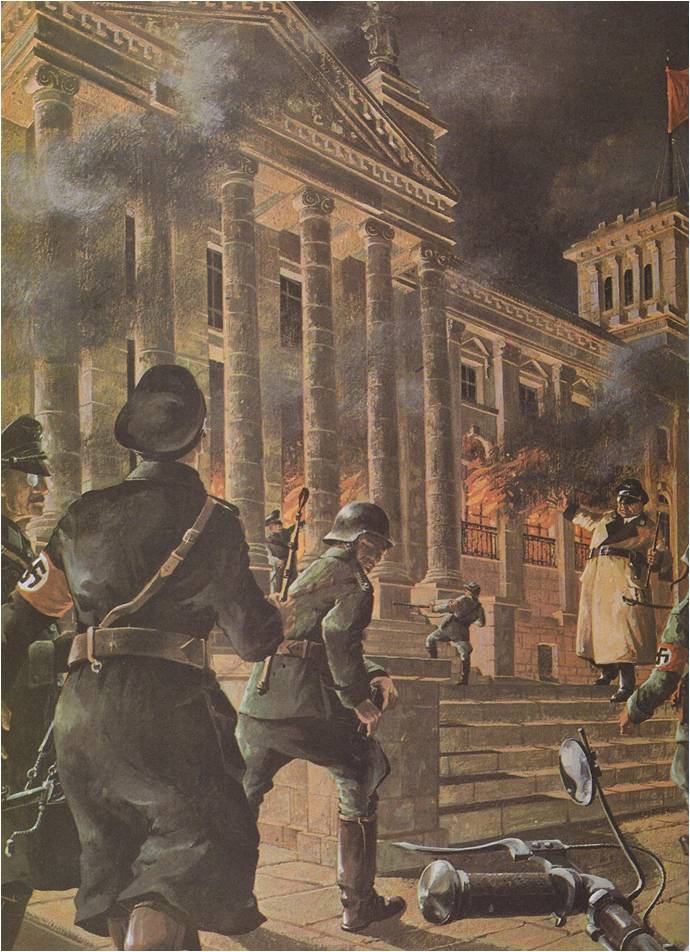

Like Mussolini in Italy, Hitler had come to power by peaceful and legal means, but he still did not have all the power he wanted. He dissolved the Reichstag, as he had the right to do as chancellor and called for a new election to be held on March 5, 1933. The Nazis had no doubts of their success. Everything was in their favour. The leading party in the Reichstag, they now controlled the press and the government owned radio system. Their brown-shirted hoodlums beat up Communists, Socialists and members of Catholic trade unions. Hitler cracked down on the Communists, forbidding their meetings and closing their press. He hoped for a Communist uprising, so that he could smash it and win the full support of the people. When the Communists refused to oblige, the Nazis decided to arrange an incident and blame it on the Communists.