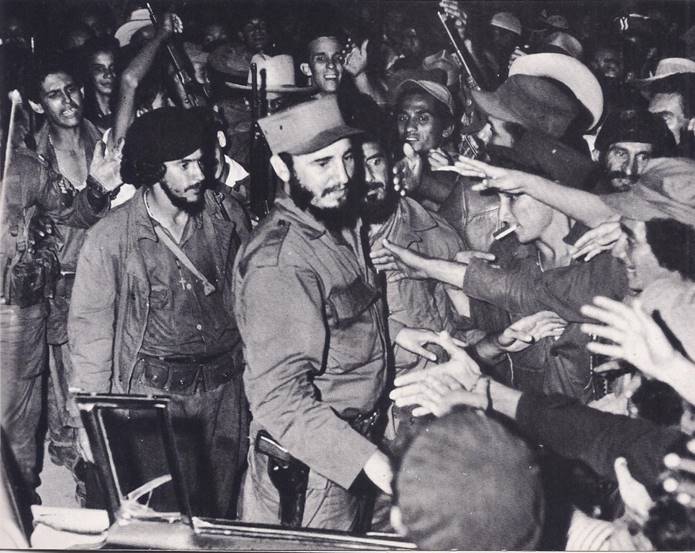

One of the sources of trouble was Cuba. In 1956 a small group of revolutionaries, led by a 29-year-old lawyer named Fidel Castro, rose up against the government of Fulgencio Batista. Batista was perhaps the most brutal dictator in all Latin America. Few people believed that Castro had much chance for success, for Batista was as efficient as he was cruel and his soldiers were well armed. Within two years, however, Castro had gathered around him a large, well-organized band of guerrillas. By January of 1959, Batista had fled the country and Castro had taken power. His amazing victory seemed a triumph of democracy and he was enthusiastically welcomed when he visited the United States later that year.

The friendship between Cuba and the United States soon turned sour. Castro seized sugar plantations and industries owned by American companies and the Eisenhower administration demanded that he at least pay the companies for the property he had taken. Castro answered that these companies had been mistreating the Cuban people for more than fifty years and that Cuba owed them nothing.

Even more disturbing was Castro’s increasingly close ties to the Communist countries. Soon he was calling himself a “Marxist-Leninist”– by which he meant a Communist and had set up a dictatorship on the Russian model. He allowed only one political party in Cuba and permitted no opposition or disagreement. Furthermore, he made Cuba into a base for revolutionary activity against the other governments of Latin America. By 1960, Castro was about to openly join the Communist camp and soon he would be receiving substantial aid from Russia to make up for the loss of trade with the United States. A conflict had arisen between the United States and Russia over a country that was only ninety miles from American shores.

Another source of trouble was Laos and South Vietnam, which had been unstable since the Geneva conference of 1954 had divided French Indo-china into four countries. Laos was on the verge of civil war as its three factions — the pro-west conservatives, the pro-Communists and the neutralists fought for supremacy. The situation in anti-communist South Vietnam was nearly as serious. The government was unpopular with the people and was engaged in an expanding war against guerrillas trained by Communist North Vietnam. President Eisenhower felt that if Laos and South Vietnam fell to the Communists, the rest of Southeast Asia would collapse soon after and he sent more and more military aid to the two countries.

Still another source of trouble was the Congo, a huge, rich country in the heart of Africa. In 1960 Belgium suddenly gave the Congo independence after eighty years of the worst kind of misrule. The Belgians had done nothing to prepare the Congo for independence and when they left, the country fell into chaos. In a furious competition for influence, the East and the West each sent in agents who tried to win over the Congolese government At the same time, the two main provinces declared that they intended to secede and set up governments of their own. The problem was handed over to the United Nations, but, for the first time, the cold war had reached Africa.

Finally, there was the “U-2 incident,” which occurred a few weeks before the “Big Four” conference in Paris. On May 3, 1960, the United States announced that a plane gathering weather information was lost after having probably strayed over Russian territory. Two days later the Russian government stated that it had shot down an American high-altitude plane, called the U-2, which had been taking photographs of Russia. The United States denied that such a plane was in the vicinity of Russia. But on May 7, Khrushchev declared that the pilot of the plane, Gary Powers, was alive and had confessed. In other words, the United States had been caught in a flat contradiction. Even worse, it had committed an illegal act by sending a plane into Russian air space.

On May 11, President Eisenhower, obviously hoping to save Gary Powers’ life, said that he knew about the U-2 flights and had approved them. This admission may have saved the pilot’s life, but it gave Khrushchev an excuse to wreck the Paris peace conference, which took place at the end of May. In a rage over the U-2 incident, he insulted Eisenhower in public and withdrew his invitation to Eisenhower to visit Russia later in the year. The leaders of the two greatest powers in the world were no longer on speaking terms.

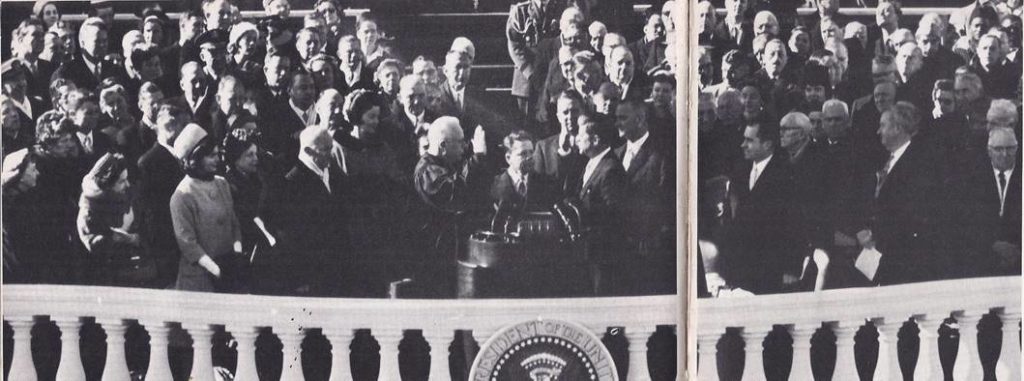

Then, on January 20, 1961, John F. Kennedy succeeded Eisenhower as President of the United States. Khrushchev said that he wanted to meet Kennedy and discuss some of the problems he would have discussed with Eisenhower in Paris. Kennedy, too, showed that he hoped for better relations with the Communist countries. In his inaugural address he asked Russia to cooperate with the United States “to invoke the wonders of science instead of its terrors. Together,” he went on, “let us explore the stars, conquer the deserts‚ eradicate disease, tap the ocean depths and encourage the arts and commerce.”

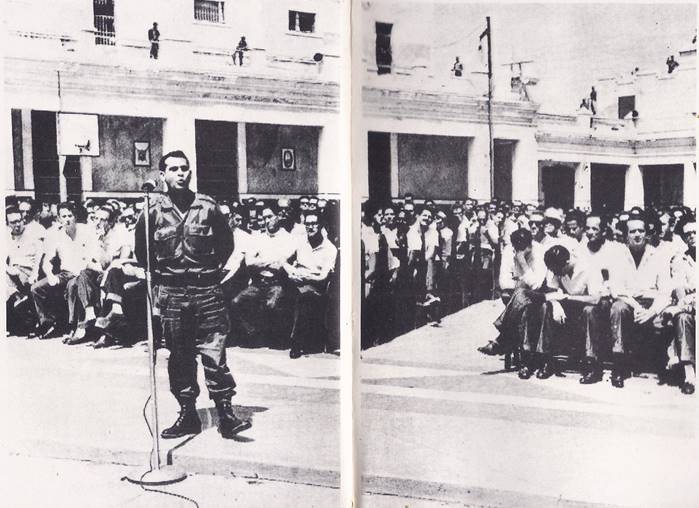

Within several months after Kennedy took office, the Communists were attacking him and calling him an “adventurer.” The reason was that on April 17, 1961, several thousand anti-Castro Cuban exiles, armed and trained by the United States, landed in Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. Before they could move from their beachhead, they were captured by Castro’s troops. President Kennedy decided not to launch a full-scale attack on Cuba in support of the invasion. He wanted to avoid the risk of a general war; besides he knew that such an attack would be resented everywhere in the world, particularly in Latin America. Although the invasion had been planned before he became President, he had permitted it to take place and he accepted full responsibility for its failure.

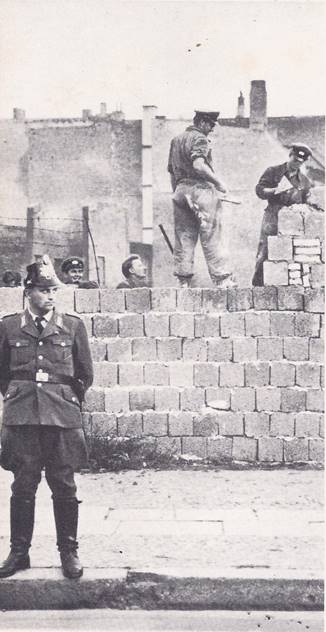

Meanwhile, a crisis was brewing over the issue of West Berlin. West Berlin was like an island deep within Communist East Germany and it was an embarrassment to the Communists because it provided refuge for the thousands of people who fled East Germany every year. Khrushchev wanted to seal off this escape route and for some time he had been insisting that the American, British and French occupation armies leave West Berlin. The Western nations refused; it was plain to everyone that if they withdrew their troops the city would fall to the Communists.

In the summer of 1961, Khrushchev announced that Russia would soon turn over its military responsibilities in Germany to the East German government. The Allies were alarmed, for East Germany, unlike Russia, had no agreement to recognize Allied military rights in West Berlin. The Allies stated that they would refuse to deal with East German authorities. The situation might then lead to violence and Kennedy backed up the Allied position by informing the American people of the possibility of war, by calling up the reserves and by sending more American troops to West Germany. But the danger passed when Russia quietly backed down and the military alert ended before the year was up. In August of 1962, the East Germans cut off the escape route by building a high, thick wall around their part of the city and the Russians soon dropped the issue of West Berlin.

They had other reasons, however, for disliking Kennedy. In 1961 he boldly committed the United States to a much more active role in South Vietnam’s war against the guerrillas. Eisenhower has sent only several hundred military advisers to South Vietnam; Kennedy increased the number to about 15,000. He hoped in this way to bring the fighting to a quick end and to prevent the Communists from taking over Laos.

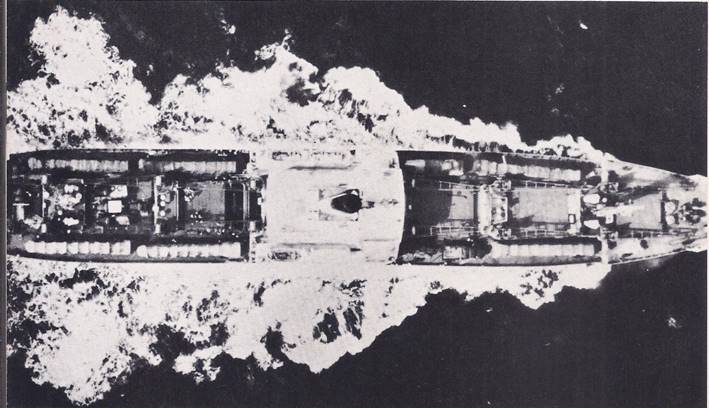

It was against this background of worsening relations between the United States and the Soviet Union that the great Cuban missile crisis arose in 1962. On the afternoon of October 23, 1962, the American people were surprised by an announcement from the White House that President Kennedy would speak to the nation over radio and television that night. They were even more surprised when they learned from the broadcast that the United States faced perhaps the most serious crisis in its history. Kennedy said that American planes had flown over Cuba recently and had brought back photographs showing that missile bases were under construction — bases capable of firing rockets upon the United States. The American government had known that thousands of Russian technicians were stationed in Cuba; now it knew exactly what they were doing there.

Millions of tense Americans watched their television screens or listened to their radios as Kennedy bluntly told them, “The transformation of Cuba into an important strategic base by the presence of these large long-range and clearly offensive weapons of sudden mass destruction constitutes an explicit threat to the peace and security of all the Americans. . .” It could be seen from Kennedy’s remarks that the danger was not simply that a potential enemy could bomb the United States; that could be done from bases inside Russia. The danger was that Fidel Castro might lay his hands on these “offensive weapons of mass destruction.” This the United States could not and would not permit, for there was no telling what Castro might decide to do.

To deal with this threat to the safety of the United States, Kennedy announced that a “strict quarantine” would be immediately imposed on all ships carrying offensive military equipment to Cuba. The ships would be searched and if they carried such equipment they would be turned back. If they resisted, they would be attacked. The “quarantine,” or blockade, was meant only to prevent further offensive military supplies from reaching Cuba, but what if Cuba already had enough supplies to complete the building of the bases and enough missiles to make them effective? About this possibility Kennedy said nothing except that more reconnaissance flights would be made over Cuba.

As news of Kennedy’s speech spread throughout the world, people everywhere realized that full-scale war might break out at any moment. Never had the danger of nuclear destruction been so great. Twenty-five Russian merchant ships were on their way to Cuba. Would they resist if American warships tried to stop them? The United Nations Security Council met in an extraordinary session and Secretary General U. Thant asked the United States to end its blockade and the Soviet Union to remove its missile bases from Cuba. Neither side did as he asked. President Kennedy insisted that he would end the blockade only if the Soviet Union first removed the bases.

It was apparent that Kennedy’s action had caught the Russians by surprise. They seemed confused. On the one hand, they made threatening statements against the United States. On the other hand, their representatives at the United Nations continued to deny that missile bases existed in Cuba — even after the United States produced photographs that disproved them, but the Russian ships in the Caribbean did not resist when American destroyers came steaming up to inspect them.

On October 26, however, the situation took a sudden turn for the worse. New evidence revealed that the missile bases were being rapidly completed. The blockade, therefore, meant little; it could not stop the construction of the bases and they were the real threat to the United States.

On learning that work on the bases was still going on, Kennedy made a momentous decision. He announced that unless construction of the bases stopped at once, they would be bombed. This would surely be the start of war, for the Soviet Union was Cuba’s ally and protector and would come to her aid. The issue now lay between Khrushchev and Kennedy. They had refused to allow other countries of the United Nations to intervene in the dispute and the fate of the world was in the hands of two men.

Then, on the following day, Khrushchev wrote an open letter to Kennedy. He promised to dismantle the missile bases and take home all the rockets and other offensive weapons — on one condition. The United States would have to dismantle its rocket bases in Turkey. “You are worried by Cuba,” Khrushchev wrote. “You say that it worries you because it is a distance of ninety miles by sea from the coast of America, but Turkey is next to us. Our sentries walk up and down and look at each other.”

This seemed to be a reasonable point, but to insist on it at this stage amounted to blackmail. In his reply, Kennedy refused to accept the condition. He said that if the Soviet Union removed its bases in Cuba and permitted the United Nations to inspect them the United States would end the blockade and not attack Cuba.

The next day, October 28, Khrushchev gave in completely. He agreed to all of Kennedy’s terms, in a letter that was astonishingly mild. “In order to eliminate as rapidly as possible the conflict which endangers the cause of peace,” he wrote, “the Soviet Government . . . has given a new order to dismantle the weapons which you regard as offensive and to crate and return them to the Soviet Union.” The crisis was over. The United States had won a great victory in the most frightening encounter in the history of nations.

President Kennedy had shown tremendous courage and wisdom. A number of his advisers had recommended that Cuba be attacked at once, regardless of the risk, but he decided to give Russia a way out; he did not force Khrushchev to choose between war and complete surrender. Khrushchev, too, had shown courage; he had proved that he was a responsible man who would rather suffer personal humiliation than bring on a war. In one respect, however, his acceptance of Kennedy’s terms was not a defeat for Russia. By preventing the conquest of Cuba by the United States, he had kept Castro’s Communist regime alive — something worth much more to him than rocket bases.

The people of the world were immensely relieved, but there were few who did not expect that the Soviet Union would try to get back at the United States in some way and that there would be a new series of conflicts in the cold war. Surprisingly, nothing of the sort happened. Instead, a new spirit of friendship sprang up between the two countries. Both of them declared their intention to live at peace and to seek agreements on the problems that divided them. Khrushchev made no more threatening gestures or statements about West Berlin. Kennedy quietly removed American missile bases from Turkey. Kennedy then went even further. Each side, he felt, had become too hardened, too rigid, too self-righteous in its attitude toward the other and this attitude must be changed if the two countries were to reach important agreements.

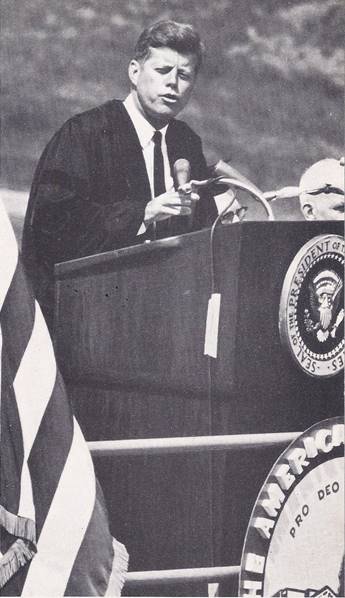

Kennedy expressed these ideas on June 10, 1963, in a remarkable speech at American University in Washington, D.C. “As Americans,” he said, “we find Communism repugnant as a negation of personal freedom and dignity. But we can still hail the Russian people for their many achievements in science and space, in economic and industrial growth, in culture, in acts of courage.” He pointed out that the United States and Russia had never been at war with each other and he reminded America that “no nation in the history of battle suffered more than the Soviet Union in the Second World War.”

It was the first time since the start of the cold war that a head of state of either country had shown such a willingness to concede something to the opposing side. Kennedy made it clear that he was still hostile to Communism as a philosophy and a way of life. He wished only to emphasize that, despite their differences, the United States and the Soviet Union could live in peace and learn to understand each other better. But Kennedy also had something specific in mind when he delivered his speech — a treaty with Russia banning nuclear testing in the atmosphere. He had already spoken to the Russians about it and they had been agreeable.

For years the world had been clamouring for an end to the testing of atomic and hydrogen bombs, which were contaminating the air with deadly radioactive fallout. Neither the United States nor the Soviet Union, however, would give up testing so long as each believed the other might gain an advantage in the race for nuclear superiority. By 1963 they had come to the conclusion that nothing more could be gained from further testing, for each now possessed enough bombs to destroy the other many times over. This fact, plus the new spirit of trust that had arisen, made the agreement possible. The Test Ban Treaty was drawn up in August, 1963, and within a year more than a hundred nations had signed it. The treaty was the most important agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union since World War II. Furthermore, it gave Kennedy and Khrushchev reason to believe they could reach new agreements on outstanding issues and establish closer cultural and economic ties. It was as though these two men, having gone through the ordeal of the Cuban missile crisis, in which they held the fate of mankind in their hands, had come to an understanding about world affairs. Never, if they could help it, would they allow such a thing to happen again and so, out of a terrifying crisis had come hope for the future.