In 264 B. C., the people of Rome met in a noisy session of their assembly. The question before them was: “Peace or War?” The Roman legions had proved their strength in winning all of Italy. Now the time had come to decide whether or not to risk the troops in wars away from the peninsula.

Meeting with the assembly was a representative from Messana, an independent town on Sicily, just across the narrow channel from the tip of Italy. Troops from Carthage had attacked the town and captured it. Now Messana begged for help from Rome. The Senate, knowing well the power of Carthage, wanted to say no. In the assembly were many men who had fought in the legions, men who were proud and sure of their strength. When the agreements dragged on, they clamoured for a vote and the assembly voted for war. Dido’s curse – the burning hatred between her city of Carthage and Rome, the city of Aeneas – had come true at last. Even if the legend of Dido was only a story, the war itself was curse enough. From one Sicilian town it spread to half of the Mediterranean, a full-scale war between the greatest powers of the West. Once begun, it went on for 119 years and ended only when one of the two powers was utterly destroyed.

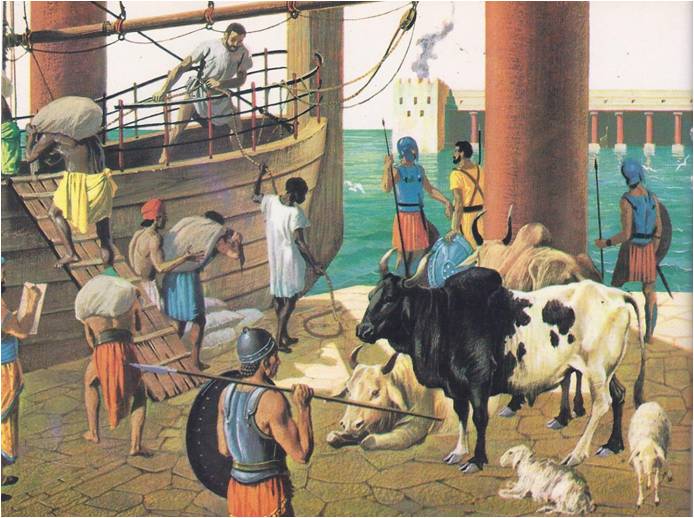

Carthage was perhaps the richest city in the world, the international headquarters of merchant-princes who could afford to buy anything – luxuries, men, ships or cities. It was three times the size of Rome. It had rows of magnificent buildings and two fine harbours, one for merchant vessels and one for ships of war. The city was just as famous, however, for its dishonesty and cruelty. The god of Carthage was Baal, a greedy, cruel god of gold and fire. His great bronze statue in the centre of the city held out its hands to receive human sacrifices and feed them into the flames on its sacred hearth.

A NAVY FOR ROME

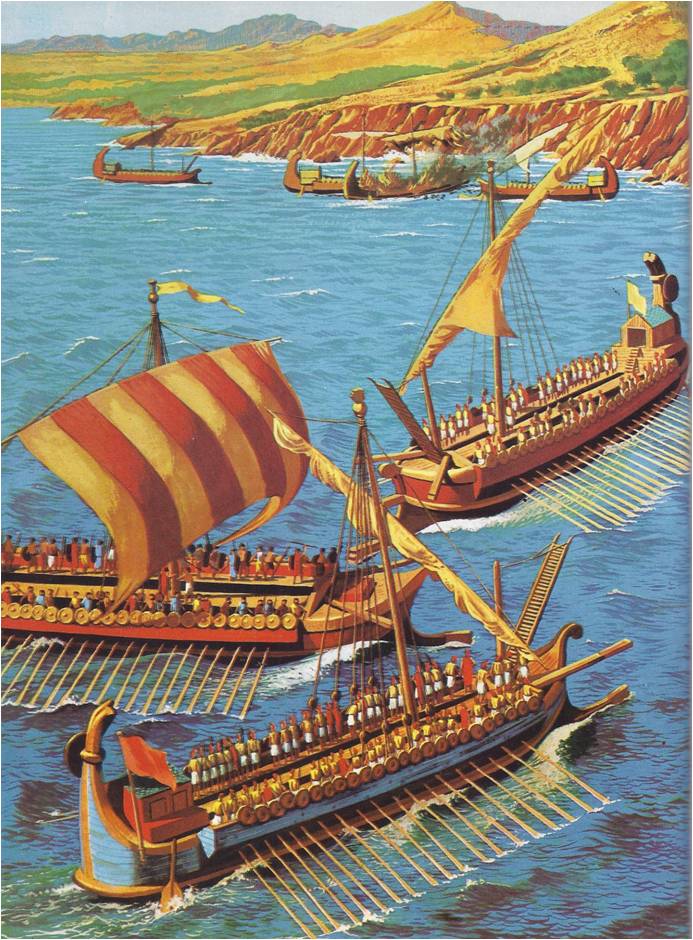

Baal had brought luck to his people. Their city stood beside the narrow stretch of ocean that was squeezed between Sicily and the African coast. Taking control of the channel, the Carthaginians had cut the Mediterranean in two and made the western half their own. Their colonies dotted the shores of Spain, North Africa and Gaul. The island of Corsica was theirs, Sardinia and much of Sicily. To guard these valuable possessions, they had the strongest fleet of battleships in the world.

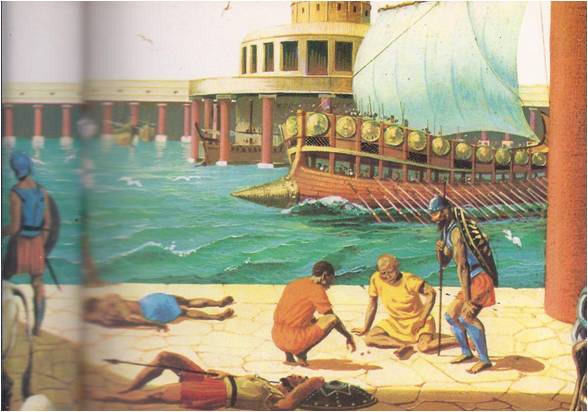

The Romans who voted to go to war with this great sea power had no navy at all. Being Romans, however, they saw they has another job to do – and did it. In two months’ time, with one captured battleship to study and some Greek sailors to advise them, they built a fleet of more than one hundred five-decked ships of war. While the ships were being built, Italian farmers learned seamanship by sitting on benches on the sand and practicing rowing.

When the ships were ready and the rowers at last put their oars into water, the new navy sailed south. In the first battle, the untried Roman seamen defeated a Carthaginian fleet. Some of the credit for the victory went to an improvement the Romans had added to their ships: a drawbridge, fastened near the prow of each vessel, with a hook at its free end. When a Roman ship pulled close to an enemy war ship, the bridge was dropped, its hook slammed into the enemy’s deck and Roman marines dashed to attack.

THE WAR WITH CARTHAGE

The war, which had begun on land, became a series of the greatest naval battles ever fought in the ancient world. When a storm wrecked their entire navy, the Romans built another. When these ships were sunk by a fleet from Carthage, there was no money in the state treasury to pay for building more. A Roman army was left stranded in Africa and miserably beaten. Carthaginian raiders sailed boldly along the Italian coast, attacking the towns and harbours.

Then the Roman citizens dug into their own pockets and their wives gave up their jewelry. Another army was raised and 200 more ships were somehow built and paid for. When the new fleet put to sea, it hunted down the ships from Carthage, sank many of them and chased the others back to Africa. Carthage was forced to beg for peace. It offered to give up its claims to the cities in Sicily and the Romans agreed. They were tired and desperately needed time to build up their strength. Twenty-three years of war had cost them 500 ships and the lives of 200,000 men.

“Rome looses battles but never a war,” the Romans liked to say – and they often proved it. Defeated, the Roman wolf licked its wounds, got to its feet and attacked again. When one army was destroyed, two more seemed to spring from the earth to take its place. Rome’s soldiers came from the farms and hills of Italy in almost endless numbers. When the Romans had first captured the towns on the peninsula, they had had the good sense to make the people their allies rather than their salves. They had given some, like the Latins, special rights in the Republic. Now Rome could count on these cities to add cavalry and archers to its own enormous armies.

Rome could not count on the courage of its soldiers. They were disciplined as well. The consuls elected to command the armies were the only law once the troops left Rome and execution the only punishment for neglect of duty, disobedience, or cowardice. Few Roman soldiers were tempted to run to escape death on the battlefield.

In battle, every man was well protected by the tight, well-ordered formations which Roman armies always used. Legions made up of 4,500 men or more were divided into 1,200 light infantrymen, 3,000 heavy infantrymen who carried both javelins and heavy short swords and 300 horsemen. On the battlefield, the heavy infantry, the main fighting force, was drawn up in three lines: young soldiers in the first line, seasoned men in the second and veterans of long experience in the third. In each line there were gaps between companies, covered by the line ahead or behind. If the fighting was hard, the tired young men of the first line pulled back through the gaps and the next line went to the enemy. If still more force was needed, the third line moved up. Horsemen and light infantry were also drawn up in strict formation. A Roman legion was a huge war machine in which every soldier had his place. He did his job and kept to his formation. He went on fighting until he was killed, or the enemy surrendered, or his captain changed the orders.

When the war with Carthage broke out again, as it did when both sides had had time to recover their strength, Rome’s power was in its well-disciplined troops. Year after year, hundreds of thousands of me came from the countryside to fill the legions. The Carthaginians had no such endless supply of soldiers. Against the legions, Carthage’s strength was strategy, the skillful maneuvering of troops that make it possible for a small army to defeat a big one. The new war became a contest between Roman power and the brilliant strategy of one Carthaginian commander, Hannibal.

Hannibal had known soldiering and war from his childhood. His father, the great general Hamilcar, had taken him along on the campaigns he led against the Spaniards. Rome and Carthage were officially at peace, but the Carthaginians still hated Rome. At nine, Hannibal swore that he would be Rome’s enemy as long as he lived. At the age of twenty-six, he was given the Spanish command his father had held and was determined to make good his oath.

The campaign Hannibal planned against Rome was so bold and daring that his officers gasped when they heard it. With Rome in control of the seas, Hannibal said he would attack by land, taking his army through the Pyrenees Mountains at the top of Spain, then west across Gaul and over the Alps into northern Italy. By 218 B. C., all his preparations had been made and he started out from Spain with an army of 40,000 Spaniards and Numidian horsemen.

When the news reached Rome, the city’s generals and military advisers were not greatly worried. Hannibal’s plan was impossible, they said. They decided, however, to take no chances. They sent an army to stop him when he reached Gaul but Hannibal bypassed the Roman army; he was saving his men for the fight in Italy. The Roman commanders in Gaul decided to go on to Spain and attack the troops Hannibal had left behind. The mountains, they said, were defence enough for Italy.

HANNIBAL CROSSES THE ALPS

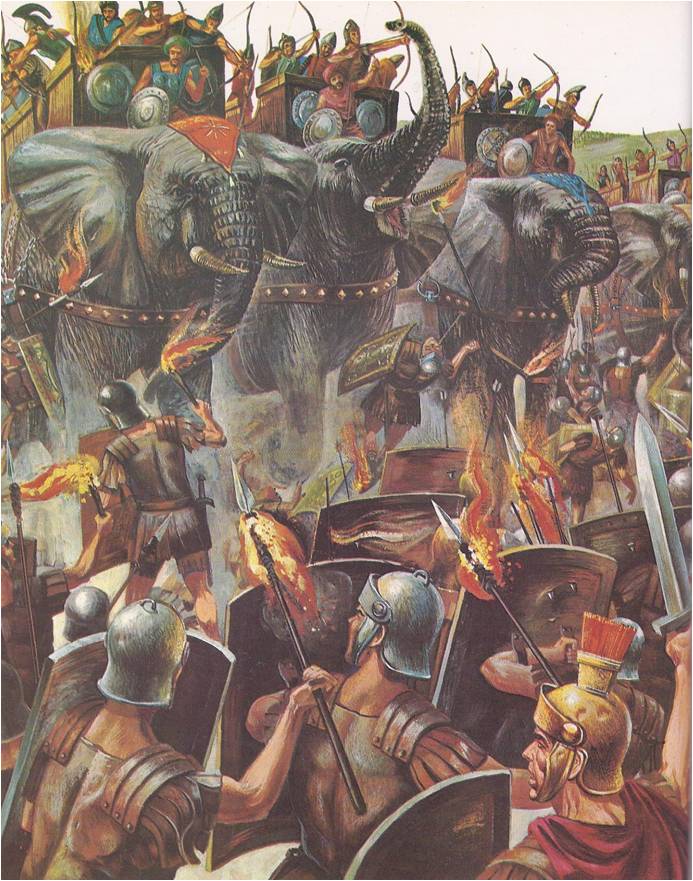

Hannibal came to the Alps in early autumn and began the climb up the steep, treacherous trails just as the first snows were falling. The long line of his army wound around the white mountains. It went along the edges of ravines where a man’s misstep meant death and through narrow passes where the rocks had to be chipped away to allow the war elephants to get through. Hannibal seemed to be everywhere along the line, urging on his hungry and half frozen soldiers. He supervised the hauling of animals and supplies up the mountains and spoke the solemn words of farewell at the brief funerals of the men who died along the trail.

Late in September, he brought his army into the Po Valley at the northern end of Italy. He had done the impossible; he had defeated the Alps. It was a victory that matched the triumphs of Alexander. He had not yet fought the war he had come to fight and only 26,000 of his 40,000 troops had come through the mountains alive. Against these, Rome could call up 770,000 citizen-soldiers and allies.

Two great armies marched north from Rome, planning to crush Hannibal’s forces before they could leave the Po Valley. Instead, the Romans were taught a bitter lesson in battle tactics. With his tired, outnumbered men, Hannibal outflanked the confident legions and chopped them down. The message that the Romans sent back to the Senate was short: “We have fought a great battle and we have been defeated.”

It seemed that Hannibal had only to march to Rome to conquer it but he did not go to the city. He had no heavy war machines – the catapults and battering rams needed to break down the defenses of the great city – and Rome’s defenses were strong. That became the story of the war, year after year. Hannibal’s strategy brought him victories whenever he met a Roman army on the field, but he could not touch the city. Rome, though safe from capture, was unable to field an army – or a commander – that could win a battle against Hannibal.

Meanwhile, Hannibal could go where he liked on the Peninsula. He spent the winter in the north, giving his men a rest. In the spring, he headed south and on the way, destroyed two more armies from Rome. Never before had the Roman Republic suffered such costly defeats or faced such danger. The senate and the assembly agreed to appoint a dictator, Fabius Maximus, to take charge of the city’s defenses. Fabius knew Rome’s strength and weaknesses well and he tried to explain them to the citizens. It was wrong, he said, to send more men to be killed by Hannibal. Rome could win the war only by waiting; sooner or later, Hannibal would run out of soldiers and supplies. The Romans were impatient and refused to take his sensible advice. They called him Cunctator, “the slow-poke”.

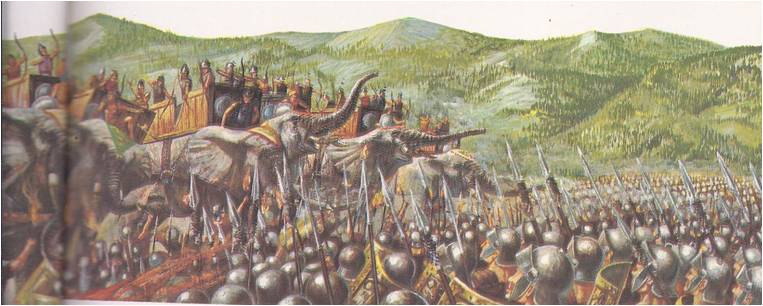

New commanders were elected, men who were anything but slow to act. They marched an army of 54,000 soldiers south to a place called Cannae – straight into a trap. When the two enemies came onto the field, the armies of both were in strange new formations. The companies of Roman soldiers were not arranged in the usual checker-board pattern. Instead, they were massed together in huge, tight blocks. Their commanders, sure of their strength in numbers, meant to drive these blocks of men straight into Hannibal’s front line, push it back and smash it.

THE BATTLE OF CANNAE

Hannibal, too, had a plan. He knew that he was weak in numbers. He also knew that his cavalry was better than that of the Romans and he intended to take advantage of both his weakness and his strength. He strung out his Spanish and Gallic infantry along the centre of his line, knowing that they would be pushed back. He placed his Libyan cavalry on either side of them and his crack Carthaginian horsemen at the ends.

The Romans attacked. The mass of legionaries rumbled across the field, crashed into the enemy line and pushed. In the centre, the Gauls and the Spaniards fell back, but the Libyan cavalrymen held their ground. Under the pressure of the attack, the line slowly bent until it was shaped like a crescent – with the Romans inside the curve. Then the Libyans began to move toward the centre, drawing the crescent more tightly around the legionaries.

The wind whipping across the field blew dust into the Roman’s faces and the sun shone into their eyes. Again Hannibal had planned wisely. He had placed his men on the field to take advantage of the prevailing wind and the position of the sun. Furthermore, the legionaries were packed together so closely that they could hardly swing their swords. Hannibal had not foreseen this; it was a gift to him from the Roman commanders who had ordered the new formation.

While the Roman infantry were pushing forward, the Carthaginian horsemen scattered the Roman cavalry. Now the Carthaginian cavalry turned back, attacking the Roman footsoldiers and turning the crescent into a deadly circle. The ranks of the legionaries broke in confusion, but there was no way for them to escape. Hannibal’s troops closed in and cut them down.

For Hannibal, it was a splendid victory, proof again of his skill in the arts of war. For Rome, it was a disaster, the greatest in the city’s history. Twenty-five thousand Romans were killed at Cannae and 15,000 were taken prisoner. The battle had other results. As the news spread across Italy, many of the towns that had been Rome’s allies decided to make peace with Hannibal. Wealthy Syracuse switched to the Carthaginian side and then the Capua opened its gates to Hannibal without a fight.

In the years that followed, the darkest of the war, the Romans at last decided to take Fabius’ advice. When they had raised twenty-five new legions, they kept them safely away from Hannibal. They used them to attack the towns which he had captured or persuaded to desert the cause of Rome. A huge force was sent to besiege Syracuse. At Capua, a double circle of Roman armies sat outside the walls, waiting for the city to starve or surrender. The tide of war was beginning to turn.

Hannibal brought his soldiers to the gates of Rome and camped in the plain of Latium, hoping to frighten the citizens into calling home their troops. They refused to be frightened. Inside the stout walls of the city, the people held an auction to sell the land on which he had built his camp. A Roman paid a good price for it, certain that he would have use of it before long. When Hannibal turned his back on Rome and once more marched south, not one legionary had been called back from Syracuse or Capua. In 211 B. C., those two cities surrendered to Rome. Hannibal sent for reinforcements from Spain. They made their way through the Alps but were met and destroyed by four Roman legions – the first defeat of Carthaginian troops in Italy.

SCIPIO TAKES COMMAND

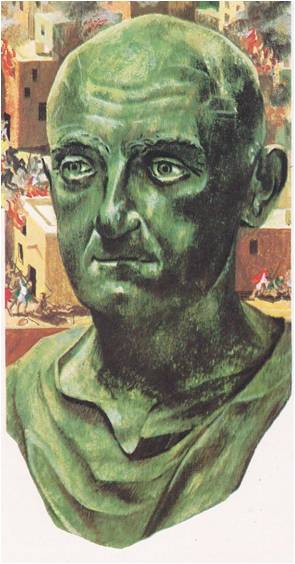

Meanwhile a young Roman officer named Scipio had begged to be given the command of legions in Spain. Scipio was only twenty-five and he had never had full command of an army. Like Hannibal he had grown up in a world of soldiers and again, like Hannibal, he came from a family of generals who had made their names fighting for Spain. His father and his uncle had been killed there. Now Scipio asked to be allowed to avenge their deaths. The citizens were impressed with his show of courage and they gave him the command, hoping that he would know what to do. In three years, Scipio learned his way about Spain and won many of the Spaniards to the Roman side. He turned his half-trained soldiers into efficient fighting men and pushed the Carthaginians to the sea. When he hurried home, eager to do more, the Romans knew that they finally had a commander to match their troops.

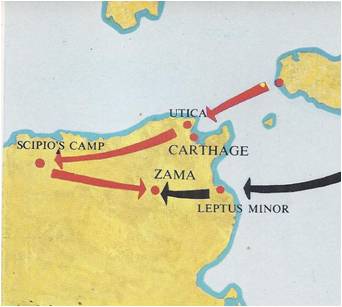

Scipio asked for an army to invade Africa and attack Carthage itself. The expedition set out in 204 B. C. and again the young commander led his army to victory. Twice he defeated the strongest forces which the Carthaginian merchants could hire to defend their city. Carthage, fighting for its life, now ordered Hannibal back to Africa. In 203 B. C., after 15 years of campaigning in Italy, he sailed home. He had conquered the Alps, but not Rome.

In Africa, on a field near the town of Zama, he once more faced the Romans. At Zama the legions were led by a general as young and as brilliant as Hannibal himself had been when he first invaded Italy. With Scipio, Rome had both numbers and strategy on its side; the contest between the two cities was no more equal. At the start of the battle, Scipio lined up his infantry and cavalry in almost the same formation which Hannibal had used at Cannae. Hannibal was prepared for that, but he simply could not match the strength. Wherever he sent his soldiers during the long, terrible day of fighting, Scipio had shifted his men there first. Late in the afternoon, when the Carthaginian cavalry fled from the field, Hannibal called a halt to the slaughter and admitted he was beaten.

Carthage surrendered. Scipio sailed home to be honoured in Rome with the new name Scipio Africanus, Scipio of Africa. Hannibal, too, went home – to share the city’s defeat. The Romans could not be comfortable while Hannibal was still free. They ordered the leaders of Carthage to hand him over to them. He fled to Syria, remaining there until that country, too, became dominated by Rome. Then, unwilling to be the prisoner of his sworn enemies, he killed himself. In the same year, 195 B. C., Scipio Africanus died.

The Romans still feared the power of Carthage, which might someday attack them again. In the senate, an old statesmen, Cato, always finished his speeches with the words, “Carthage must be destroyed!” Many Romans agreed with him and when they found an excuse to attack their old enemy, they voted for war again.

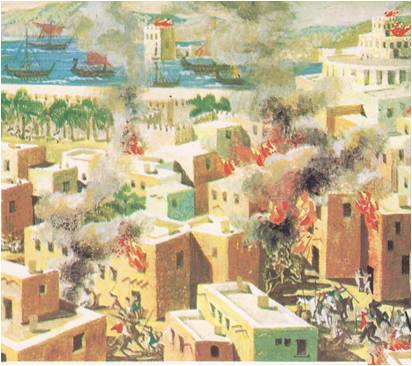

Roman soldiers camped outside Carthage for nearly three years before they managed to break through the thick walls and take their city. The people begged for mercy, but the Romans had been dreaming of revenge for too long. The 50,000 Carthaginians who lived through the street-fighting were rounded up and sold into slavery. The fortifications of their city and its rows of shining buildings were pulled to the ground. The great bronze statue of Baal was broken up and the city was set on fire. Roman priests solemnly prayed for the goddess Juno to leave the doomed city and go to the temple which waited for her in Rome. Then a sacred plow was dragged through the ashes. Salt was sown in the scorched ground so that nothing would grow and a curse was pronounced on any man who dared to build on it again. Thus the Romans marked the death of the richest city in the world.

THE POWER OF ROME

Africa became a Roman province and in the same year – 146 B. C. – Corinth in Greece was also demolished by the Romans. It was a reminder to the Greeks that they, too, were under the power of Rome. Macedonia, Alexander’s old kingdom, had been made a Roman province two years earlier. Spain and some of Gaul already belonged to Rome. By 129 B. C., there was a Roman province in Asia, too and even Egypt had decided that it was safer not to challenge a power that never lost a war.

In 264 B. C., when the Romans first voted to risk their troops in foreign lands, Rome was but one of five giants who jealously watched over the Mediterranean Sea. In the East, there were Egypt, Asia Minor and Macedonia. In the West, besides Carthage, there was Rome, the youngest of the giants, untried and unknown. Kings, emperors and cities of the East were tempted, like Carthage, to test the strength of the newcomer. Like Carthage, they met defeat. To the Romans, conquest was simply another job that had to be done.

By 129 B. C., only one power, Rome, held the Mediterranean Sea and the Romans began to call it Mare Nostrum, “Our Sea.”