The period from 610 to 717 was one of the darkest in Byzantine history. During that time, the edges of the empire crumbled under the pressure of powerful enemies. A people from northern Italy, the Lombards, conquered more than half of Italy. In central Arabia, the Arab tribes had joined together under the religion of Mohammed and marched against their neighbors. They took the kingdom of Persia, invaded Palestine and in 658 captured Jerusalem. The conquering Moslems, as the followers of Mohammed were called, swept on and soon took over Syria and Egypt. They marched along the northern shore of Africa and took Carthage in 697, then sailed across the Mediterranean and captured Spain.

By this time the empire seemed all but doomed. It had been reduced to Asia Minor, the Balkan Peninsula and southern Italy.

Shortly after Leo III had been crowned emperor he was forced to defend Constantinople during the Arab siege of 717-718. Later he drove them back on the Taurus front. After saving the empire from the Arabs, he organized the country into military districts and placed a military government over each of them. This system, together with Justinian’s fortresses, made the empire’s defenses stronger than ever before.

The empire reached the height of its glory under Basil I and his descendants, a period lasting from 867 to 1057. Most of the emperors of this period were brilliant military leaders and good administrators. Under them the empire regained its strength, beat back the Arabs in South Italy and in the East forced the Arabs back to the Euphrates, overran Cilicia and Syria, and pushed down into Palestine to the gates of Jerusalem. On the European side, Basil II crushed the mighty empire of the Bulgars.

DIPLOMACY AND TREACHERY

Byzantine emperors often used treachery to weaken their enemies. They kept their treaties, but they stirred up trouble between enemies by playing them off against each other. Justinian once wrote this note to a Hun prince: “I directed my presents to the most powerful of your chieftains‚ intending them for you. Another has seized them declaring himself the foremost among you all. Show him that you excel the rest; take back what has been filched from you, and be revenged. If you do not, it will be clear that he is the true leader; we shall then bestow our favour upon him and you will lose the benefits formerly received by you at our hands.” Such notes were sometimes enough to set off wars between barbarian chieftains. In later centuries it was the policy of the empire to cause trouble between great western states to prevent them from joining together against the empire.

The empires missionary policy helped it live at peace with its neighbours. Christian monks and priests were sent into barbarian lands to spread the true religion and to make friends for the empire. They carried medicines. They introduced new methods of tilling the soil. They made bricks and built churches and organized community life. They sent local chieftains to Constantinople to see the wonders of civilization. The chieftains were often persuaded to leave their sons in the city for schooling and when these young men returned to their native lands they carried many civilized ideas with them. In this way the missionaries built an invisible frontier of Christianity and civilization hundreds of miles beyond the borders of the empire.

Dealings with other nations were usually carried out through visiting kings and ambassadors. It was the policy of the emperors to be very formal with such visitors and to try to impress them with the might and glory of Byzantium. This was not difficult to do, for Constantinople was then the greatest, most prosperous and most dazzling city on earth.

Visitors could hardly fail to be impressed with the great domed cathedral and the imperial buildings, all highly decorated with crystal, rare woods, ivory and gold. In the imperial palace, the visitors were amazed at the remarkable water clocks, the golden lions that roared, the golden birds that sang and the throne chair that slowly rose and remained suspended in the air. How the throne was suspended is not known. Visitors were treated to elegant banquets, with music and dancing, and showered with precious gifts.

With such diplomacy, the empire won a faithful following among the Slavs, Armenians, Italians and Caucasians. These carried its influence back to their homelands and throughout the civilized world. Constantinople was looked upon as a centre of learning and culture by the Croats, Bulgars, Serbs and Russians. From Byzantium they received their religion, their arts and their ideas about government.

BYZANTINE EDUCATION

The education of the young was not neglected. Byzantine boys could go to school at the age of six. After learning to read and write Greek, they studied the Greek classics and memorized large portions of Homer and the Bible. Later they studied composition, philosophy, arithmetic‚ geometry, music and astronomy. If they wished to go on, they could study law, medicine and physics. There were no schools for girls. There were women doctors, which suggests that the daughters of many wealthy families received their education from private tutors.

THE ARTS OF BYZANTIUM

After the fall of Rome to Germanic invaders, the Latin language lost much of its standing in the East. It was not commonly used in government offices even in Justinian’s day and by the eighth century, Greek had become the official language of the empire. Greek was also the language of Byzantine authors. They added very little to world literature, but some of their works on religion greatly influenced Western thought. Among their best authors were a number of able historians, such as Procopius‚ Agathias, Menander, Psellus, Cinnamus and Nicetas. To them the world owes most of its knowledge of Byzantine history. Very little fiction was written. Only one novel is considered outstanding, a romance entitled Barlaam and Josaphet, probably written by John Damascene. There were no great poets but some of the hymns written by Romanus and John Damascene are still sung today. These hymns and a few folk tunes are all that remain of Byzantine music.

Some of the empire’s greatest accomplishments were in the field of art. Out of a blending of Roman, Greek and oriental influences‚ the artists of the empire created a new style of art, rich in pattern and color.

The cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople was its greatest triumph in architecture. With the construction of that building the Byzantines mastered the problem of placing a dome over a square. Domes became important features on all new churches in the city, for they added height and splendor to the interior. The Church of St. Irene had two domes. The cathedral of the Holy Apostles was built in the form of a cross with a large dome at the crossing and smaller ones at the ends of the four arms. That church was destroyed by the Turks, but was widely copied in other lands. The best example is St. Mark’s church in Venice.

Byzantine churches were not particularly attractive from the outside. Their interiors gleamed with polished marbles of many colors and were richly decorated with colorful designs and goldleaf mosaics. The Byzantine artists were at their best in the decorative arts. One of their greatest contributions was the mosaic. It is a form of art in which pictures are made with small pieces of colored stone or glass. Mosaic artists made daring use of color and were fond of placing their images against a background of gold leaf. Mosaics were used in churches not only to decorate walls and ceilings but to instruct simple worshippers by showing scenes from the lives of Christ and the Virgin. There were also mosaics showing various prophets and emperors. Mosaic floors were decorated with trees and birds and attractive patterns.

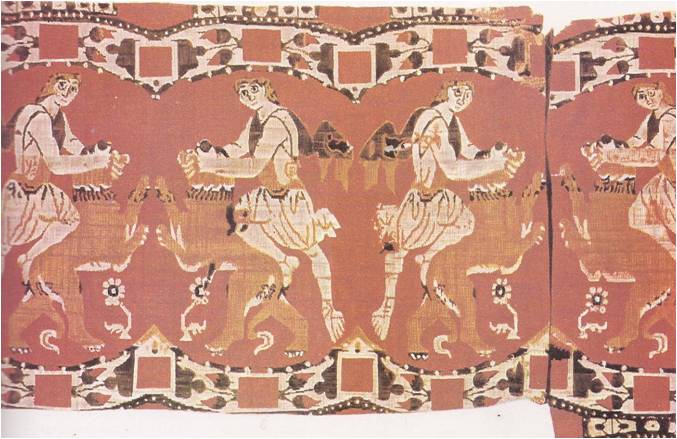

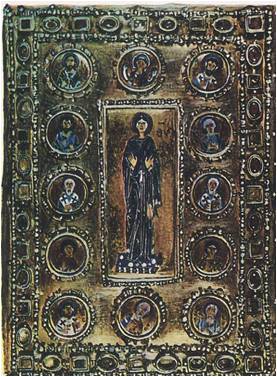

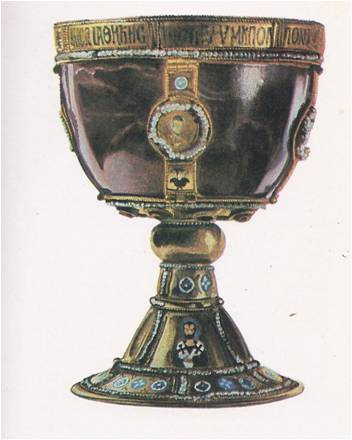

Many Byzantine artists liked to work with rich materials such as gold, ivory, enamel, precious stones and rare woods. Because these materials were expensive, much of the finest work was done on a small scale. Small objects were made out of finely carved ivory, bronze inlaid with silver and rare woods. Frames for small religious paintings blazed with gold and sparkled with jewels. Trays, boxes, vases and other small objects were often decorated with a kind of enamelwork on metal, called cloisonné. The artists used small patches of colored enamel to form patterns and figures, with each patch of color outlined by a thin band of metal. The figures and patterns were very simple at first, but by the eleventh century the technique had been highly perfected and the artists could produce portraits and delicate dancing figures.

The creations of Byzantine artists were known and admired in many lands, for they made up most of the empire’s export. Goldsmiths produced jewelry, cloisonné and bronze inlaid with silver. Other items of export were brilliantly dyed silks, embroidered silks, dyed skins, cloth of gold, brocades, linen and carvings in ivory and semiprecious stone.

Up to the seventh century, one of the chief imports was raw silk from China. Two Nestorian monks, agents of Justinian, smuggled eggs of the silkworm out of China in a hollow cane making it possible for the empire to become in time a large producer of raw Silk. Pearls, precious stones and spices were imported from countries in the East. From Russia came timber, furs, wheat, honey and salted fish; from Persia came rich carpets and fine wines. Constantinople also carried on a brisk trade in slaves with both Russia and Venice.