THE LONG STRUGGLE between France and England, known to history as the Hundred Years’ War, was not really a war — and it lasted more than a hundred years. Rather than a war, it was a series of separate battles, with periods of uneasy peace between and it lasted from 1338 to 1453. It was time of misery for both sides, but the French lost more men and saw much of their land devastated. By the end of the Hundred Years’ War, important changes had taken place in both countries. In France, the years of conflict weakened the power of the nobility and led to the rise of a strong middle class. Warfare would never be the same; the English victories showed that mounted knights, weighed down by heavy armour‚ were no match for archers with longbows and the final battles were decided by artillery.

The cause of the war was that the English still held the Duchy of Aquitaine, a rich land in southwestern France and were determined not to lose it. The French were equally determined to drive them out. A further complication was the situation in Flanders. The English sold raw wool to Flemish manufacturers, who wove it into cloth and sold a good part of it back to the English. This trade was important to England and even more so to Flanders and both countries were anxious that nothing should happen to disturb it. The English also kept a watchful eye on the Flemish ports, which could serve as a base for a French attack on England or an English attack on the continent. Flanders was not a completely independent state; its ruler, the Count of Flanders, owed allegiance to the king of France. England tried to destroy the count’s authority by stirring up the Flemish against him. Meanwhile, France aided England’s enemies in Scotland.

In 1326, the Count of Flanders, carrying out the orders of King Philip VI of France, arrested and imprisoned all Englishmen in Flanders. Edward III, the king of England, promptly struck back. He stopped the trade in woolens with Flanders, bringing the Flemish woolen industry close to ruin. He then claimed the throne of France, insisting that he had more of a right to it than Philip. The Flemish townsmen, who had always hated being under the thumb of France, threw their support to Edward and in 1340 he took the title of King of France.

The title itself meant nothing; to make good his claim, Edward would have to invade France. To keep him from landing troops on the coast of Flanders, the French gathered a fleet of ships at Sluys, the harbour for the city of Bruges in Belgium. On June 25, 1340, English ships completely destroyed the French fleet and won mastery of the sea that would last for thirty years.

For five years there was a little land fighting that decided nothing, but in 1346 the English landed at Normandy and began marching inland. The French rushed to stop them and the two enemies met at the city of Crécy. The French army, which greatly outnumbered the English, included many powerful nobles. Among them were King John of Bohemia and his son Charles.

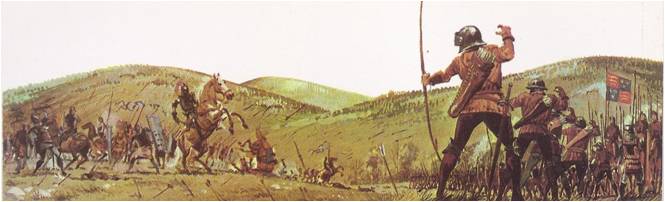

Against the French, the English used the new weapon, the longbow and the new battle formation they had already tested against the Scots — two long wings of archers protected by men-at-arms on foot. As the mounted French knights charged a storm of English arrows came whistling at them and men and horses fell to the ground. In their heavy suits of armour, weighing as much as two hundred pounds, the knights were all but helpless and they were killed by the hundreds. Again and again the French knights charged — and again and again they were brought down by the English archers.

King John of Bohemia, old and blind, refused to retreat. He ordered his knights to lead him into battle so that “he should have one fair blow at the English.” It was no use: his courage only brought him death. By the time night fell, the French, the strongest military power in Europe, had been thoroughly defeated. England had taught the world that the knight on horseback no longer ruled the battlefield, although a century would pass before the French took the lesson to heart.

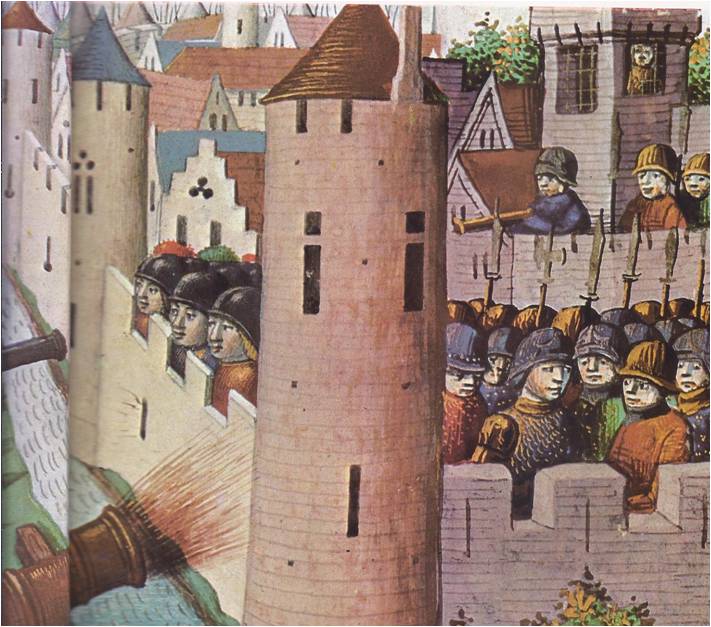

The English followed up their victory at Crécy by laying siege to Calais, an important seaport in northern France. When the city finally fell, in 1347, the English drove out the French townsmen and brought in English colonists. Besides opening the way into France, England now had a new market to take the place of Flanders.

The war was interrupted by the terrible plague known as the Black Death and it was not until 1356 that fighting broke out again. Led by Edward III’s son, who was called the Black Prince because of his custom of wearing black armour, the English again overwhelmed the French, this time at Poitiers. King John II of France was captured, along with many noblemen and was taken to England to be held for ransom. The English treated him as a guest, even giving him ample spending money. An easy-going, pleasure-loving John, who preferred gambling and hunting to the duties of ruling a country, thoroughly enjoyed his stay in England. Meanwhile, however, English soldiers were staging raids in France and Frenchmen found life hard in their disorganized land. To make matters worse, many French nobles tried to restrict the peasants and get more work out of them and in 1558 the peasants rose in revolt. They were put down by troops still loyal to the crown. John realized that it was high time he returned home and he agreed to pay — or rather that France would pay — an enormous ransom: 4,000,000 gold crowns, or about thirty million dollars. Although John was well-meaning, he was not a good king and many people said he wasn’t worth that much money.

Nevertheless, John agreed to the ransom and in 1360, at the village of Brétigny, he signed a treaty with Edward. Edward gave up his claim to the French throne. In return, besides the ransom, England was given a large slice of France, including the provinces of Poitou, Guienne and Gascony. John died four years later, but not before he had done something which would cause trouble to France for years to come. He made his son Philip duke of the Free County of Burgundy. As heads of an independent state, the rulers of Burgundy would prove to be dangerous rivals to the monarchy of France.

Edward, too, made a mistake when he appointed his son, the Black Prince, as governor of England’s newly won territories in France. The Black Prince was no match for Charles V, who became king of France after the death of John. With the help of his constable, Bertrand du Guesclin, Charles won back much of the land that had been given to England.

Serious fighting broke out again in 1415, when Henry V was king of England. France was now torn by civil war between the Burgundians and the supporters of the French monarchy and Henry decided to take advantage of the situation. After making sure that the Burgundians would not oppose him, he landed on the coast of Normandy with an army of 12,000 men, 8,000 of whom were archers. He began marching north and near the village of Agincourt the French tried to stop him.

Again the French outnumbered the English, again the French relied on mounted knights in armour‚ again the knights were brought down by the English arrows and slaughtered. Like Crécy and Poitiers, the battle of Agincourt ended in a complete victory for the English and a triumph of archers over mounted knights.

The English went on to conquer Normandy and in May of 1420, they and the French signed the Treaty of Troyes, which named Henry as the heir to the French throne. To seal the bargain‚ Henry married Catherine, the daughter of the French king, Charles VI. In 1422, however, Henry V died. The new English king, Henry VI, was an infant and a regent ruled in his place. A few months later, the French king died, leaving as heir Charles VII.

Charles was only nineteen years old and weak and sickly besides. He was terrified of the English and had no control of his courtiers. They took bribes, stole government money and insulted Charles to his face. While they made themselves rich and lived in luxury, Charles shambled about in shabby clothes and could not even afford to buy a pair of good shoes. As a ruler, Charles was a joke — and the truth was that he was not yet officially the king. Although he was the heir to the throne‚ he had never been crowned, because the English held the city of Rheims and the French would acknowledge no man as their king until he was crowned and consecrated in the Rheims cathedral.

In 1424, in violation of the Treaty of Troyes, the English pushed into central France. They then turned south to invade Charles’ domain and began their campaign by laying siege to the city of Orleans, on the Loire river, about eighty miles south of Paris. Once Orleans fell, the way would be open for them to take all of southern France. Orleans would have fallen — if it had not been for a seventeen-year-old peasant girl known as Joan of Arc.

JOAN OF ARC

Joan had lived all her life in the village of Domrémy, in the province of Vaucouleurs. Unable to read or write, she had spent her days herding cattle and sheep, helping in the fields at harvest time. Like most of the peasants around her, Joan was religious and often she prayed to the saints whose statues stood on pedestals in the village church. Then the saints began to appear to Joan in visions and she heard their voices speaking to her. The voices told her that she had a mission to perform. She must go to King Charles and take him to Rheims to be crowned and she must drive the English out.

“I am a poor girl,” Joan said. “I do not know how to ride or fight.”

“It is God who commands,” said the voices.

Time after time the voices spoke to her and at last she went to the commander of the French garrison at Vaucouleurs. At first he laughed at her, but she persuaded him to give her an escort of six soldiers so that she could get to Chinon, where Charles was holding court. Dressed in soldier’s clothes, she traveled three hundred miles through territory held by the English and their Burgundian allies.

At Chinon, Charles and his court were both amused and amazed at this simple peasant girl who said that God had sent her to save France. They were impressed by her sincerity and Charles turned her over to a committee of churchmen. After questioning and observing her for three weeks, the committee reported that she was indeed good, honest and might well have been chosen by God to carry out his will.

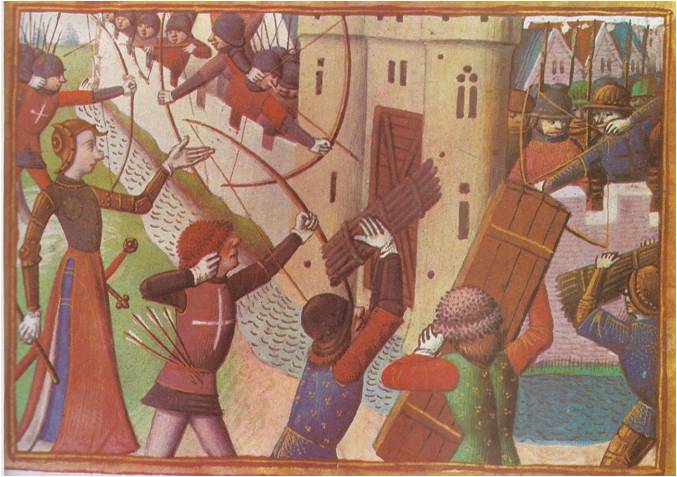

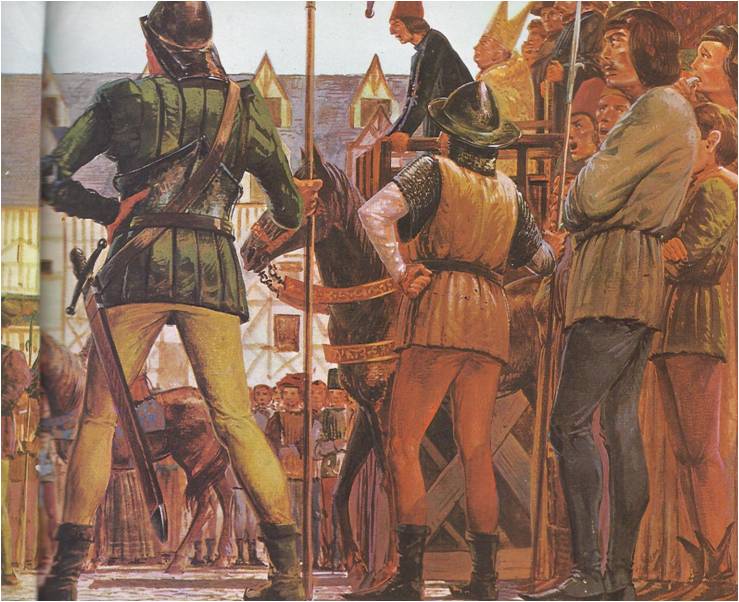

Meanwhile, the English were still besieging Orleans and the king’s counselors were desperate. If Joan could do nothing else, perhaps she could put some spirit into the French troops; at any rate, there was no harm in trying. Charles gave Joan a horse, a suit of white armour and a banner on which she inscribed her motto: “Jesus and Mary.” Leading a small body of troops, she joined the army at Orleans.

The rough French soldiers soon began to look upon her as a saint. She was with them when, in 1429, they attacked the English outside Orleans. As a chronicler later wrote, “Before she came, two hundred Englishmen used to drive five hundred Frenchmen before them. After her coming, two hundred Frenchmen could beat and chase five hundred Englishmen.” Although Joan knew nothing about warfare, she took part in the battle and was wounded in the shoulder by an arrow. Inspired by her courage and daring, the French fought fiercely; they freed the city and forced the English to retreat.

Joan remained with the army while it cleared the English and Burgundians out of the Loire valley. The French commanders wanted to move north against Paris, but Joan insisted that Charles brought to the Cathedral at Rheims for his coronation. In July of 1429, while Joan stood proudly beside him, holding her banner, Charles was crowned and consecrated. Kneeling before him, Joan said, “Gentle King, now is fulfilled the will of God that I should raise the siege of Orleans and lead you to the city of Rheims to receive the holy coronation, to show that you are indeed the king and the rightful lord of the realm of France.”

Joan was still not satisfied; every Englishman must be driven off French soil. Charles, who did not care for war and only wanted to live quietly and in peace, was prepared to negotiate with the English and the Burgundians. More and more, he found Joan a nuisance. Anxious to be rid of her, he left her to fight on with anyone willing to follow her banner. In May of 1430, during the siege of Compiégne, she was captured by the Burgundians, who sold her to the English for 10,000 pounds.

The English were delighted. They were eager to show that Joan was a witch; after all, what else could explain how she had so suddenly turned the tide of the war? Only by witchcraft could an ignorant peasant girl have rallied the French troops. Those Englishmen who had little belief in witchcraft were willing enough to use it as an excuse to destroy the person who had unified the French against them. Once Joan was dead, perhaps the English soldiers would regain their confidence and go into victory. The English turned her over to certain representatives of the Church, who placed her on trial in Rouen on charges of heresy and sorcery.

These men had been deeply disturbed by Joan. According to them, she challenged the authority of the Church when she claimed to have received a message from God through the voices of the saints. They insisted that only priests could interpret the will of God to man. They could not allow anyone to claim personal communion with God. This was heresy, the kind of belief which was beginning to arise in Europe and which the Inquisition had been organized to put down. Besides, the Bishop of Beauvais, who conducted the trial, was under control of the English, who wanted Joan dead.

The English were delighted. They were eager to show that Joan was a witch; after all, what else could explain how she had so suddenly turned the tide of the war? Only by witchcraft could an ignorant peasant girl have rallied the French troops. Those Englishmen who had little belief in witchcraft were willing enough to use it as an excuse to destroy the person who had unified the French against them. Once Joan was dead, perhaps the English soldiers would regain their confidence and go into victory. The English turned her over to certain representatives of the Church, who placed her on trial in Rouen on charges of heresy and sorcery.

“WE HAVE BURNED A SAINT!”

No help came to Joan from Charles. She had made him a king, but then she had become an embarrassment to him and he was glad to have her off his hands. No help came to her from anyone. Alone, day after day, for ten weeks, she faced her inquisitors, who tried to get her to confess. They asked her question after question. They showed her torture instruments which they could use, they threatened her with burning at the stake. She could still live if only she repented and admitted her guilt, she would be sentenced to life imprisonment — and she would save her immortal soul.

At last, weary and confused, Joan signed a confession she scarcely understood. The next day she disowned it. She could not be untrue to herself and her faith. “Whatever I have said was from fear,” she said. “I told you the truth of everything at the trial.”

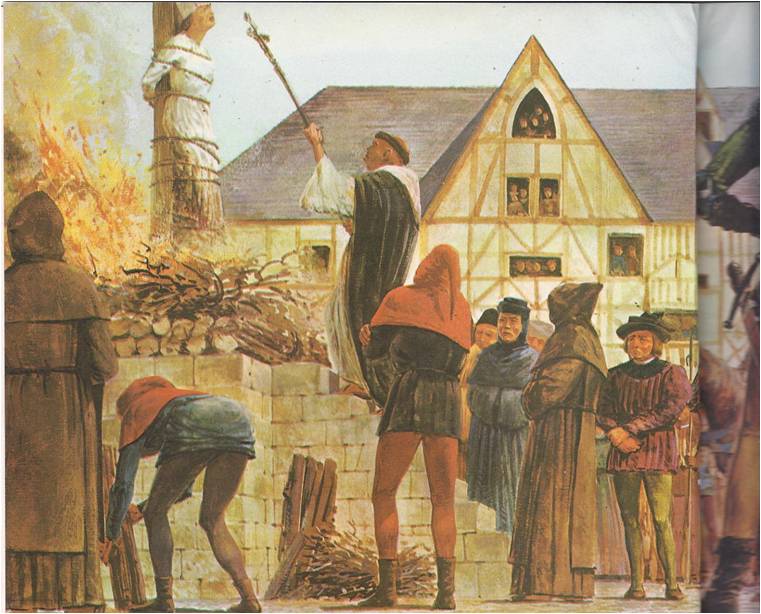

She was immediately sentenced to death and on May 30, 1431, she was burned at the stake in the marketplace of Rouen. As the flames rose, she gazed upon a crucifix and called on the name of Jesus. An English soldier who watched her die cried out, “We are lost! We have burned a saint!”

The English soldier was later proved to be right. In 1456 the Church re-examined her trial, condemned the court and found her not guilty of the charges of witchcraft and heresy; in 1920 she was declared a saint.

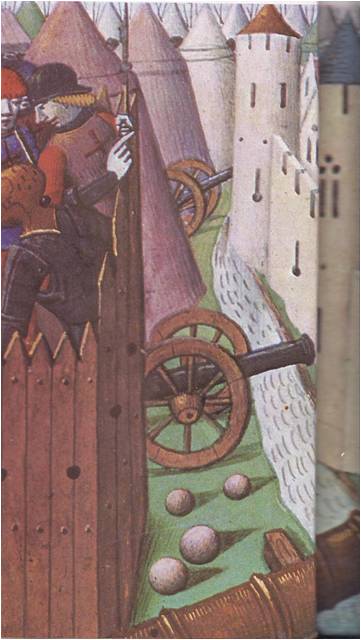

After Joan’s death, the long war dragged on. In 1435 the Duke of Burgundy broke with his English allies and signed a peace treaty with the French. The following year, a French army recaptured the great city of Paris. In 1439 the Estates General gave Charles the right to raise troops and to tax the people directly. This not only strengthened the French monarch enormously, but also allowed Charles to carry out a thorough reorganization of the army. By 1449 the French had the finest artillery in Europe and Charles renewed the war against the English. In four years the English were almost completely driven off French soil; all that they could manage to keep in their hands was Calais.

So it was, in 1453, the Hundred Years’ War came to an end — but France now had a new rival, the powerful state of Burgundy. This state had come into being in 1363, when King John II of France had given it as a fief to his son. By conquest, by treaty, and by marriage, the Burgundian fief grew until it included all of Flanders and the Low Countries, which would later be known as Holland and Belgium. The Burgundian court was one of the richest and most splendid in Europe and the Burgundian dukes were ambitious. They hoped to extend their territories and establish a kingdom.

When war broke out between France and Burgundy, the king of France was Louis XI. He was far different from any of the monarchs France had had before him. Homely, with long, thin legs and a sharp-nosed face that usually wore a sour expression, Louis had no use for luxury and court ceremony. He wore shabby black clothes and a felt hat with images of the saints fastened around the crown. Louis was as practical in religion as he was in everything else; in return for his prayers, he expected the saints to give him help when he needed it.

He was always weaving plots and had a network of spies who reported to him, Louis was known as the Spider. He spent a great deal of time traveling about his country, poking his long nose into anything he felt concerned him. He stayed with members of the middle class rather than with his nobles; in fact, he relied on the middle class for support more than he did on the nobility. Louis believed he could gain more by negotiation and scheming than by battles and he had good reason to think so. In spite of his strange habits, he was shrewd, crafty and a master of diplomacy.

A UNIFIED FRANCE

Louis’ enemy, Charles the Rash of Burgundy‚ was everything Louis was not. He was handsome‚ chivalrous, courteous — and stupid. Louis outwitted him, playing for time, negotiating, making treaties, buying off Burgundy’s allies, until finally, in 1477, Charles was killed in the battle of Nancy. His skull was split open and his fleeing soldiers left his body to freeze in the mud. Louis snatched up Burgundy and some of Charles’ other territories. Louis’ great task of expanding and unifying France was completed by his heir, Charles VIII, late in the fifteenth century. Although the French monarchs would still have to fight to hold their power, they had thrown off the customs and practices of feudalism.