AT THE END of the 16th century, Brandenburg and Prussia were unimportant German lands, but the ruler of Brandenburg was clever and farsighted. He was John Sigismund, the head of the Hohenzollern family. In 1594 John Sigismund married the daughter of the idiot duke of Prussia. In 1618, when the duke died, John Sigismund became ruler of Prussia as well as Brandenburg.

There must have been many people who laughed at John Sigismund. Brandenburg was worth little, they must have thought, so why did he want an even less valuable Prussia. The nobles were the real power in both Prussia and Brandenburg and ruled almost like kings. They did not pay taxes and they treated their peasants like slaves, whipping and imprisoning them as they wished. The Brandenburgers were backward and poor. Their land was sandy and infertile; they had no great ships or ports, few industries, little trade. Their capital, Berlin, was an unimportant provincial town. Prussia was even poorer and it lay on the frozen, marshy lands north of the Polish capital, Warsaw. Prussia was separated from Brandenburg by 200 miles of hostile territory and Swedes and Poles fought for the entire area.

The Poles even claimed John Sigismund as their underling. Like earlier dukes of Prussia, he had to travel to Warsaw and kneel before the king of Poland before the Poles would accept him as duke.

In 1618, when the Thirty Years War began, John Sigismund’s weak, divided lands were completely unprotected. John Sigismund died two years later and was succeeded by George William, a timid duke. The war went on, Brandenburg and Prussia were overrun and George William did not know what to do. By the time he died in 1640, it seemed that his lands would be forever torn by war, by religious strife and by the selfishness of the nobles, who almost refused to help defend the country. But the timid duke’s son, Frederick William, had remarkable ability and a strong will. Like his father and grandfather, he was one of the seven German princes who were electors of the Holy Roman Emperor and he would be remembered as the Great Elector.

FREDERICK WILLIAM

Frederick William was twenty years old in 1640, with brilliant blue eyes and a long curved nose that made him look like a hawk. He was vigorous and loved to ride, shoot and fence. He was also well educated; as a boy he had learned Latin, Dutch, French and Polish. At fourteen he had gone to study at the University of Leyden in Holland. There the young prince from backward Brandenburg saw the finest arts of Civilization — the magnificent paintings of Rembrandt and Hals, the great Dutch ships and canals‚ the rich farms, the palatial homes of the Dutch merchants. He must have been tremendously impressed, for his whole fortune hardly equaled the riches of many Dutch traders.

When Frederick William returned to Brandenburg after his father’s death, he saw utter misery. His land was a war-torn ruin, with homeless men and women roaming the countryside. Frederick William knew that he must end the war to save his people. He also knew that he must end discord in his lands and so he was friendly to the nobles. When the nobles demanded it, he dissolved his father’s war council and put them in charge of military affairs. At the nobles’ request, he even kept Jews from settling in Brandenburg.

AN ARMY OF HIS OWN

As soon as he could, Frederick William signed a peace treaty with Sweden. A few years later, when the Thirty Years War ended in 1648, Frederick William received Eastern Pomerania, which almost linked his distant territories of Brandenburg and Prussia. Hoping to prevent war from destroying his land again, he proposed to the nobles that he keep a small army to guard against invasions. The nobles refused. When Frederick explained that the Swedes still occupied Pomerania, the nobles replied that they did not care about Pomerania. They secretly feared that with an army Frederick William might be strong enough to take away their privileges.

Then another war gave Frederick William his chance. Charles X of Sweden invaded Poland. Charles was a strange-looking king, as short and broad as a barrel, with thick lips and bulging eyes. He was a powerful warrior‚ with mighty armies that now passed within a few miles of Frederick’s lands. Now Frederick had an excuse to raise an army of his own; at the same time, he remembered the horrors of war and tried to stay neutral. Charles’s soldiers ravaged Poland and when Charles threatened to attack Prussia unless Frederick agreed to be his ally, Frederick reluctantly complied.

The Poles received aid from Austria and began to fight back, putting good armies in the field. Charles grew worried and the more he worried, the more he promised Frederick in return for his help. Finally Charles agreed to give up all of Sweden’s old claims to Prussia. Then the Danes joined the war on the side of the Poles, who became even stronger; the Poles, too, offered to abandon their claims to Prussia if Frederick would join their side. Frederick agreed. He was not particularly fond of double-dealing, but the opportunity was too good to resist. By changing sides he became the undisputed ruler of Prussia.

During the war, Frederick raised taxes without consulting the nobles. They protested that their rights were being ignored, but he told them the war made taxes necessary. He cleverly taxed the towns, not the nobles. So heavy were the taxes that the townsmen complained that they had to sell their beds to raise money. Again over the nobles’ protests, Frederick set up a permanent war council and gave it the power to raise taxes. With his army, his council and his taxes, Frederick William was almost free of the power of the nobles. He had gone far toward achieving the power of a dictator.

FREDERICK BUILDS PRUSSIA

The nobles were not really unhappy, for Frederick protected many of their old privileges. He let them rule their estates and their serfs. On their own lands they were like kings and this satisfied most of them. In the army, only nobles were officers. Many of the common soldiers were peasants and the nobles treated these peasant soldiers as they did their own serfs. They could whip or beat them almost as if they were slaves. The noble officers often spent most of their lives in the army, enjoying the rough comradeship of military life and many never married. The kings of Prussia had stationed these officers far from their own estates. With few family ties, the noblemen who were colonels and generals of the army had developed an unshakable loyalty and obedience to the kings of Prussia.

Having silenced the nobles, Frederick built up Prussia. He encouraged the persecuted Huguenots of France to come to his country and they brought their skills in farming and trade. He also allowed Catholics to settle in Prussia and Jews in Berlin. This was unusual in that intolerant age. Frederick William was a firm Protestant, but he believed that people should be allowed to worship God as they pleased. He knew that a country with different people and many skills would be wealthy and strong. When Frederick William died, Prussia was still not very wealthy or strong but he had set it well on the way.

Frederick I, who succeeded the Great Elector in 1688, was a frail and deformed man who loved ceremony and fancy living. He tried vainly to imitate Louis XIV and built a palace at Lutzenberg modeled after Versailles. He imported expensive paintings, china and tapestries and surrounded himself with musicians and artists. He founded the University of Halle and cooperated with the great German philosopher Leibniz in founding the Berlin Academy of Science. He was far too weak to make Prussia greater. Where the cultured Frederick I failed, his rough hewn son Frederick William I succeeded.

Other German princes mockingly called Frederick William “the Royal Drill Sergeant.” He was a dictator by nature and his rallying cry was: “No reasoning, obey orders!” He beat those who opposed him with his own fists. He disliked culture and cultured men and called philosophy “hot air.” Once, for a joke, he chained bear cubs to the bed of the President of the Berlin Academy of Science. Frederick William was no mere buffoon. As king he dismissed his father’s extravagant court and took over full control of the government. He said “Salvation is of God; everything else is my concern,” and he worked hard to make Prussia strong.

REGIMENT OF GIANTS

Frederick William’s greatest love was the Prussian army and he told his agents to do anything to recruit men. They even swooped down on distant German Villages on Sunday mornings‚ surrounding the churches and carrying off all healthy males coming from worship. Frederick William was wildly enthusiastic about tall soldiers. When his son-in-law gave him eight huge recruits as it gift, he hugged him, shed tears and cried “My God, what joy you give me.” Frederick William’s agents laid ambush along the roads for tall youths. They even stormed a peaceful monastery in Rome and carried off an oversized monk whom they made into a warrior. The cleverest recruiting agent was Von Borck, the ambassador to England. Von Borck’s favourite trick was hiring huge Englishmen and Irishmen to be servants to make believe Prussian noblemen. Once inside Prussia, the giants were thrown into the army. The English ambassador tried to win the release of one of these men but he was forced to give up. They laugh at me when I mention the thing,” he wrote.

The huge soldiers were organized into a special Regiment of Giants, whom Frederick William drilled himself. He dressed them in huge fur hats to make them look even taller. For them, as for the whole army, discipline was severe. If a soldier’s buttons did not sparkle, he might be beaten with a cane, while for disobedience or theft he could be hanged, shot, or burned. Under iron discipline, with daily drill in rain or sizzling heat, the Prussian army became the best fighting force, man for man, in Europe. Only the cavalry was inferior. Frederick William made the mistake of putting some of his huge soldiers in the cavalry and mounting them on oversized horses. “They were giants on elephants,” his son said, “and could neither move nor fight well. There was not a review during which riders . . . did not fall off their horses.”

To support his army, Frederick William established new taxes. The nobles protested and swore that whole provinces were being ruined, that their fortunes were being broken, that the peasants would starve or revolt. Frederick William continued the taxes. It was not the provinces that were being hurt, he said, only the pride of the nobles.

THE EYE OF THE KING

Frederick William also needed trained officials, officials to collect taxes and to run the government. At first many duties of state were performed by local officials who were not named by the king. Frederick William believed these men were lazy good-for-nothings who were paid but did not work, or were thieves who secretly raided his treasuries. So he dissolved the mint, the post office‚ the customs office and all the other independent local boards. He meshed them all into one Supreme Directory, under his own direct control.

The king controlled the Directory completely. “No one,” he said, “shall be appointed to any office unless I do it myself.” He not only appointed officials, he watched them. One morning, finding a postmaster oversleeping, he soundly whipped him. Postmasters, policemen, treasurers, secretaries — no one knew when the king might descend on them. They lived in “fear of the never resting eye of the king.” “God has given me eyes,” Frederick William said, “so that I can immediately see whether my rules and orders are given prompt attention.” He hired spies and inspectors to help him watch his officials and showed no mercy to the careless or dishonest. “Whoever steals ten reichstaler,” he said, “is to be hanged in chains on an iron gallows.” One man caught stealing twelve reichstaler pleaded that his children had been hungry and that his salary was too small to feed them all, “I forgive him the debt,” the king wrote, “but he is to be hanged.”

Frederick William encouraged native industries by taxing French luxuries, English woolens, Danish meat, cheese and almost all other foreign wares. He put tailors, who used foreign cloth out of business and he dressed the queen and princesses in rough Prussian wool that made their skins itch. To settle vacant lands, he lured immigrants with officers of free farms and livestock.

To make his people better educated and richer –so that they could pay higher taxes — he sent the Prussian youths to schools. He did not let them learn too much. He thought that “Christianity, reading, writing and arithmetic is enough, everything else is tomfoolery.” Many brilliant men, like the philosopher Leibniz, became disgusted with dictatorial Prussia and moved elsewhere. A few minor poets still wrote gay verse about shady nooks, flowers and birds, but the harsh spirit of Prussia usually discouraged writers. Nor did Prussian businessmen have much influence. If they were very lucky, they were occasionally invited to royal balls, where they were kept apart from the nobles by a rope.

FREDERICK THE GREAT

When a son was born to Frederick William in 1712, he named him Frederick and said, “Fritz must be just like me.” He chose old soldiers to educate him. From the time he was five, the king dressed him in army uniforms and took him on horseback rides, hunts, parades and army maneuvers. Although young Frederick would someday be known as Frederick the Great, as a boy he was not like his father. He enjoyed delicate French novels, paintings and he loved to play the flute. His father had said philosophy was “hot air,” but as Frederick grew up, he was fascinated by philosophy and wrote letters of praise to Voltaire, the witty French philosopher. He also grew to hate hunts, parades and army life. His father was furious. He called Frederick girlish and whipped him again and again.

Frederick planned to marry an English princess and escape to England, but his father refused permission for the marriage. Then Frederick tried to flee with two friends, Lieutenant von Katte and Lieutenant von Keith. They rode to a border village, but spies of the king seized them and the king had Frederick locked in a cell at the fortress of Küstrin.

One morning Frederick was awakened by his jailor and told that Katte would be beheaded. From his cell window he saw Katte being led to the execution block. “Oh, my dear Katte,” he called miserably, “I beg a thousand pardons.” Katte answered, “My lord, there is naught to forgive.” As Katte kneeled for the stroke, Frederick fainted.

The king soon let Frederick out of prison. He began to bend to his father’s will, to study military affairs, ride and hunt. He told his father he wished to obey “from love rather than duty,” but still the king remained angry and difficult. He was bedridden with dropsy and could no longer beat his servants, so he kept loaded pistols by the bed and threatened to shoot them. When the king’s health grew worse, he said, “What I really regret is that I shall have such a monster as my son to succeed me.” But he thought carefully about his son and one day at dinner he burst out, “Fritz, I love you with all my heart. For the first time I have really learned to know you. There is a Frederick William in you. . . . You are my dear son.” Not long after, on May 31, 1740, Frederick William died.

As king, young Frederick earned the name of Frederick the Great. He abolished torture, opened state granaries to the poor and lessened punishments for many crimes. Many people expected his reign to be gracious and peaceful, but he quickly increased the army by ten thousand men. Where his father had been cautious, Frederick was reckless and he loved adventure. Soon Prussia learned to accept the idea that a German writer later put into poetry:

Dreams of a peaceful day

Let him dream who may.

War is our rallying cry,

Onward to victory.

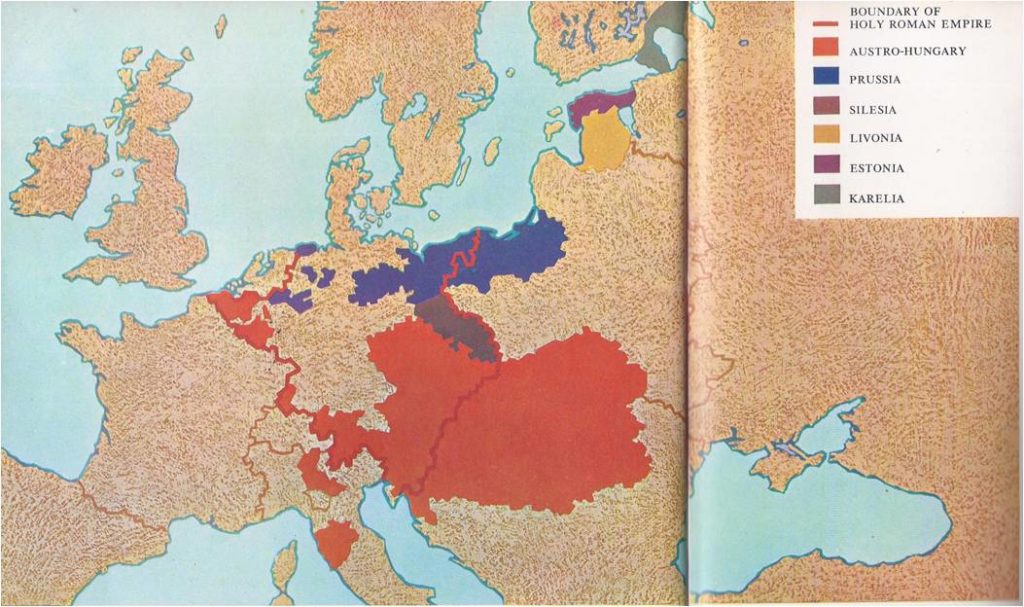

As Frederick’s thoughts turned to war and glory, his eyes turned to Silesia, a rich province of the Austrian Empire. In Vienna, the capital of the Austrian Empire, a new Hapsburg queen sat uneasily on the throne. She was Maria Theresa, a charming, warm-hearted and virtuous woman who claimed she had the heart of a king. She was a woman and by an old law no woman was supposed to be ruler of Austria. Before he died, Maria Theresa’s father had made the kings of Europe, including Frederick William, swear to accept his daughter as queen. Now Frederick decided to ignore his father’s oath. Calling together his officers, he told them, “Sirs, I am embarking on a war in which I have no ally but your valour, no resource but my own good fortune.” Then he marched his troops into Silesia.

Maria Theresa sent her army to meet the invaders. The two forces met near the village of Mollowitz, on land covered by two feet of April snow. Under the Austrian charge the Prussian cavalry line fell to pieces and the cavalry stampeded into the infantry. The confused infantry fired wildly in every direction, hitting friend and foe alike. Frederick tried to rally his men, shouting‚ “Brothers! Children! Lads! Your country’s honour!” The wild firing continued and his generals persuaded Frederick to flee the field. He rode away sure that all was lost. But the Austrian charge was spent, the cavalry bogged down in snow and mud. The Prussian marshal rallied his infantry and they advanced like clockwork, “arrow straight, as if on parade,” an observer said. The Austrians wavered, then fled. It was a great day for the victorious Prussians.

AUSTRIA LOSES AGAIN

In Vienna, Maria Theresa made heroic speeches, appealing to the honour of the Austrian nation and to the pride of the Hungarian nobles. Austrians and Hungarians rallied around her and the next spring she sent a stronger army to recapture Silesia. The Austrians furiously attacked near the village of Chotusitz, broke the Prussian line, reached the Prussian camp and began to plunder it. Frederick had shrewdly held some cavalry in reserve and now be sent these fresh horsemen into battle. They surrounded the tired Austrians and sent them fleeing. Her armies broken and exhausted, Maria Theresa sued for peace.

Two years later, the enemies were again at each other’s throats and this time the Austrians seemed unbeatable. Spurred on by their brave Maria Theresa, they had beaten off attacks by France, Spain and other countries and even occupied Bavaria. Against Frederick, however, they lost battle after battle, for he was a master of military tactics. At the battle of Hohenfriedberg he laid a brilliant trap. His soldiers pretended to make camp, then slipped away and trapped the Austrians in a mountain gully. The defeated Austrians sued for peace again. Frederick had won Silesia and he had made Prussia more important. “I will henceforth not even attack a cat except in self-defense,” he said. “I want to enjoy myself.”

VOLTAIRE IN PRUSSIA

Carrying out his plan to enjoy himself, Frederick the Great built the gorgeous palace of Sans Souci. It had a Chinese pavilion, a Greek temple, orange groves, cherry orchards and a great library filled with books. Frederick hired two famous French chefs and he ate deer meat pasties, truffles, ox-tongues with pepper and drank only champagne. He invited the philosopher Voltaire to his court. Voltaire had already written to Frederick with high praise — “You think like Trajan, you write like Pliny, you talk French with our best writers. . . . Under your auspices Berlin will be the Athens of Germany, perhaps of Europe.” Frederick and Voltaire both loved the centre of the stage too much to get on together. Finally Frederick told Voltaire,” If your work deserves statues, your conduct deserves chains.” Voltaire went home, glad to be leaving a country which by then seemed to him like a giant army barracks.

To enrich their nation, the Prussians built up Silesia. Experts poured in to start businesses, build factories, dig mines and set up banks. Silesia yielded coal, iron and textiles. Fredrick improved the lot of his subjects, making life better for the peasants on his own great lands, but he did not end serfdom in Prussia. The forced labour of the serfs was needed to build up the country, claimed the experts — especially the experts who owned serfs.

Prussia had won glory and become strong too fast and other European rulers suspected Frederick’s ambitions. In Vienna, Maria Theresa could not rest. She had once said that “to consent to the loss of Silesia would be dishonorable,” and she valued her honor above all. Maria Theresa had a clever minister named Kaunitz‚ a strange man who was frantically afraid of germs. When he was outdoors he kept a handkerchief over his face and when riding he wore a glass helmet over his head. He would never enter a sickroom and he forbade the word “death” to be uttered, in his presence. But Kaunitz was not afraid of violence and he began to weave a mighty alliance against Prussia.

PRUSSIA UNDER SEIGE

Kaunitz signed agreements with Sweden, with Russia and with France. They would invade Prussia, destroy its armies and divide up its lands. Fredrick’s spies discovered their plans. In 1756 he invaded Saxony and smashed an Austrian army at Lobosotz, then besieged Prague. Fredrick was attacked by another Austrian army, commanded by the wily Marshal Daun. Daun understood Frederick’s battle tactics and he routed Frederick and the Prussian troops. It was the start of Frederick’s time of trouble.

The Russians invaded East Prussia, the Swedes poured into Pomerania, the French seized Friesland. “I am getting so many blows,” Frederick wrote, “that I am almost stunned.” Nevertheless, he did not lose his courage. He maneuvered his troops to meet the enemy armies separately and he won many battles. He lost some, too. In 1759, at Kunnersdorf, the Prussian army was badly mauled by Russians and Austrians. Frederick had two horses shot from under him and hoped that a bullet would strike him, for he believed his cause was lost. Later he wrote to his sister, “We are all in rags. Hardly anyone got off without two or three bullets in his clothes and hats.”

Again Frederick plucked up his spirit, standing heroically against the foreign invaders, invaders who for centuries had trampled German soil. Frederick’s heroism sparked the flame of German pride. Young nobles rushed to enlist. Peasants, too, came flocking to join the army from Brandenburg to Pomerania and even from the hills of Silesia and the town; along the Rhine.

Frederick continued to fight and under the rigours of war he grew old and bent. Still, he found odd moments to enjoy his interests. In camp late at night, his soldiers sometimes heard him reciting the verses of the great poet-playwright Racine and saw him shedding tears over certain passages. He played the flute and wrote poems in French. Mostly he fought, on and on, a tired, bowed man, his face unshaven, his clothes rumpled and dirty from months of battle. Some of his advisers suggested that he admit defeat, but he remained firm. “Never will I survive the moment in which I am forced to sign a dishonorable peace,” he said.

FREDERICK REBUILDS

Gradually his enemies grew exhausted. France was being beaten on the seas by Frederick’s ally Great Britain and could no longer send money for the Austrian armies. In January, 1762, one of Frederick’s enemies, the Russian Empress died. The new Russian ruler was an imbecile who played with toys, was German by blood and loved Prussia. Russia withdrew from the war and Sweden made peace soon after. Prussia was saved. In 1763 Frederick signed a peace treaty with Austria under which he kept all his territories.

“It is a poor old man who is coming home,” Frederick said. Most of his old Berlin companions were dead and his best generals had been killed in the wars. His country had been wrecked by seven years of fighting. Frederick vowed “never to enjoy happiness while everybody suffers,” and he worked heroically to rebuild Prussia. He directed each department of the government. Millions were loaned to peasants and nobles for cattle‚ horses, seeds and timber to rebuild ruined lands. Labourers dredged rivers, cleared forests and drained swamps. For the first time, potatoes and turnips were planted on a large scale. Government experts taught English methods of scientific farming. The state also encouraged every kind of industry, building warehouses and selling raw materials cheap to manufacturers.

Frederick continued to add to Prussia’s territory. He took West Prussia from Poland in 1772, when Russia and Austria also sliced off pieces of Poland. West Prussia was the link that finally joined Brandenburg and Prussia, making the country one. Frederick fended off a weak attack by Maria Theresa’s son, Joseph II — the last attempt by Austria to retake Silesia.

A MIGHTY STATE

Prussia was now a great European power. The state was all-important and there was little freedom for individuals. Frederick continued to control every decision. The noble officials resented being only glorified clerks and sometimes they even sabotaged his plans, but Frederick watched them carefully. His intelligence and his concern for his people led writers like Voltaire to describe him as an ideal ruler and a mild man.

Under the pressure of continuous work, Frederick the Great grew more sour and dictatorial. There was truly “a Frederick William” in him just as his father had said. Many Prussians began to resent their lack of freedom, but Prussia remained a country where there was less freedom than in most other European lands.

The rulers of Prussia had had to overcome more obstacles than the rulers of any other nation that became important in Europe. They hacked the Prussian nation out of foreign soil, used every resource to build it up and preserved it by trickery and force. Only by bending the Prussians to their will, only by organizing the country like a military camp, did they succeed. Obedience, duty, discipline, military might — these were the realities by which Prussia lived; they were the source of Prussia’s strength — and of its weakness.