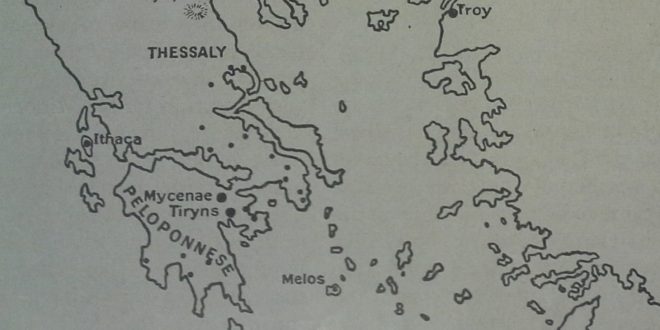

The two hundred years after 800 B.C. saw a great expansion of the Greeks by colonisation. Colonisation is a more orderly kind of migration. The Greeks now lived in numerous small communities, often no more than towns with surrounding farmlands. They are therefore called “city-states”. Some of these city-states now sent out colonies to southern Italy, Sicily and also to the Black Sea. These colonies became independent but they kept in touch with their mother-city. Miletus in Ionia sent out many of the Black Sea colonies. Byzantium, now Istanbul, was founded by Megara a city near Athens. The most important of the western colonies, Syracuse, was founded by Corinth. Sparta founded Taras (Taranto) in Italy. Marseilles in the south of France was first colonised by Greeks from Asia Minor. One of the Aegean islands founded Cyrene in North Africa. A map of the Greek world about 600 B.C., when the period of colonisation was over, has therefore to cover most of the Mediterranean. When a people expands in this way it is usual to speak of their “empire” and a map of it shows somewhere a city in extra large print, which is the capital — Babylon, for example, or Egyptian Thebes, or Rome. At this time (c. 600 B.C.) the Greek city-states and their colonies, being independent of each other, did not constitute an empire and acknowledged no capital. There were however two places which all Greeks regarded with reverence. One was Delphi and the other was Olympia.

Read More »