One day in the fifteenth century, the Turkish potentate of Babylonia decided to send gifts to the greatest ruler in Italy. He consulted his counselors and men who had traveled widely in Europe, asking them who best deserved this honour. They agreed that one Italian court outshone the rest and that his court must surely be the home of Italy’s mightiest sovereign. They did not name Milan, the home of the proud Sforza, nor Florence, the city of the clever Medici. The most magnificent court in Italy, they said, was at Ferrara, the capital of the dukes whose family name was d’Este and to Ferrara the Turkish potentate’s ambassadors carried the presents.

Ferrara was small, a mere toy state in comparison to Milan or Florence. Actually, it was not an independent state at all. Like several of its neighbours in central Italy, Ferrara had for centuries belonged to the Church. Its duke paid an annual tribute to the pope for the privilege of governing his family dukedom himself. Even so, the Turkish potentate’s advisers had made no mistake. No court in Italy could match the splendor of the court commanded by the dukes of little Ferrara.

During the Renaissance, there were many such small cities that won fame. It all depended on their rulers — the ambitious dukes or counts or sometimes, commoners who had gained riches and power. With their money, they, too, hired fine artists, sculptors and architects; they, too, collected manuscripts and things of beauty. So the small cities were as much part of the new age as Florence or Milan.

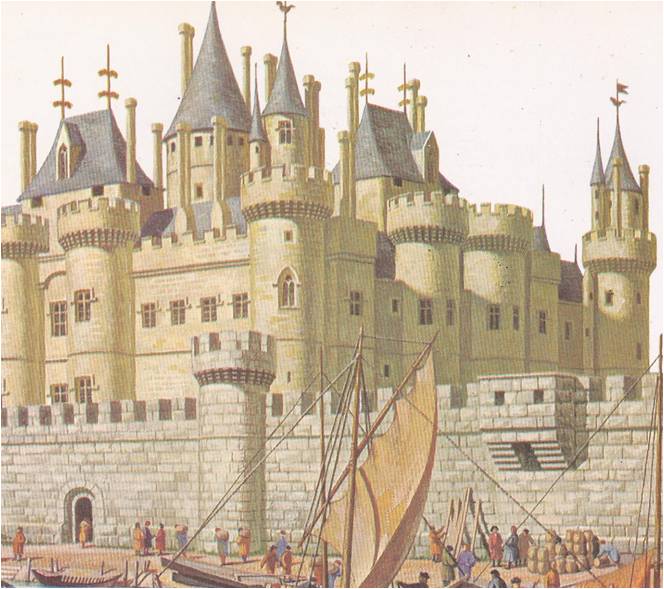

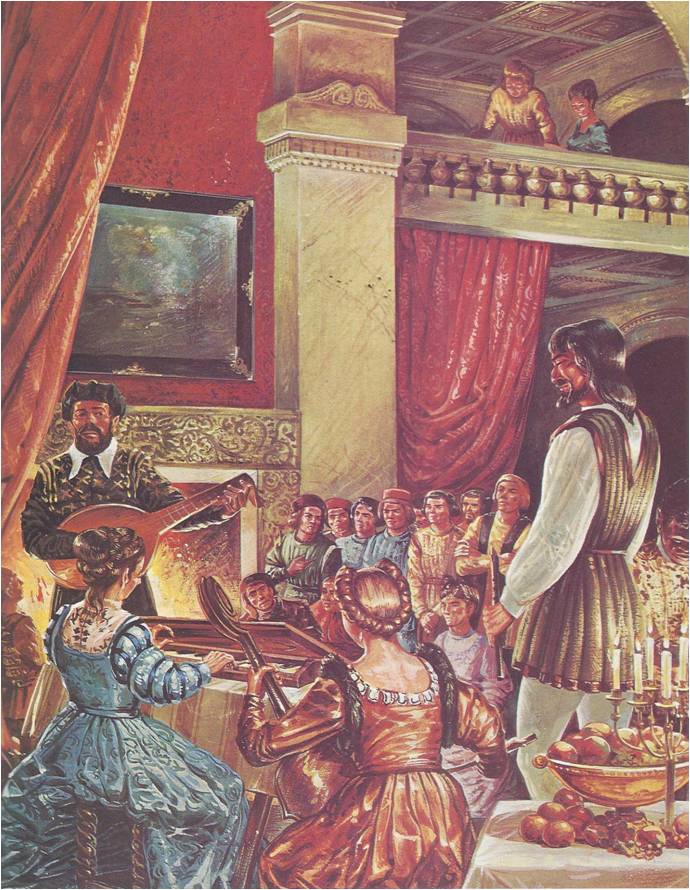

In that new age, Ferrara was a place of old fashioned grandeur. Its dukes, the d’Estes, had come to power in the last days of chivalry. In 200 years, the d’Estes had turned Ferrara into a city of palaces. There was the Palazzo de Diamante, whose outer walls were covered with 12,000 diamond-shaped pieces of marble and Schifanoia, the summer palace of the dukes (its name meant “Skip Annoyances”) Belriguardo, or “Lovely View,” was one of half a dozen pleasure palaces. Grander than any of these was the great Castello, the home of the famous court to which the Turks had brought their gifts from Babylonia. Here nobles and ladies posed on furniture decorated with gold. In hidden alcoves, courtly couples whispered of love and scholars argued noisily about the meaning of Greek words. Soft Asian carpets covered the marble floors and the walls were hung with Flemish tapestries showing knights and dragons, magical forests and tall towered medieval castles.

The people of Ferrara loved the old tales. In times long gone, before there had been a Castello, wandering minstrels from France had come to the court to sing of the adventures of Charlemagne and his knights. There were many stories and many versions of the same story, handed down from minstrel to minstrel. Years later, when the minstrels came no more, Count Matteo Boiardo, a poet in the court, decided to put the tales in order and write them down so that they would not be forgotten. In 1486, Boiardo set to work on a poem he called Orlando Innamorato, “Orlando in Love.” He told of the knight Orlando who lost his heart to Angelica, an enchantress. Orlando’s adventures were only the main thread of the poem, a pathway by which Boiardo led his listeners through a whole forest of tales. At every turning, other knights and ladies came into the story; there were wars and tournaments and mysterious castles. Whenever Boiardo finished writing down a few tales, he read them aloud at court. The courtiers were delighted with them and the poem grew longer and longer. By 1494, when Boiardo stopped writing verses, he had put down 60,000 lines and Orlando’s tale was still unfinished.

Ten years later, Lodovico Ariosto, a young lawyer who hated the law but loved poetry, began to write some new adventures of Orlando. Ariosto managed to finish his poem of 39,000 lines in ten years. Then he lugged the manuscript to his patron, a d’Este who had been made a cardinal. The cardinal looked at the heap of pages, read some of them, stared at several more, then turned to Ariosto with a look of puzzlement. “Where, Master Lodovico,” he asked, “did you find so much nonsense?”

Ariosto had named his poem Orlando Furioso –“Orlando Out of His Mind” — and, in a way, it was nonsense. The adventures were wild and impossible. There were winged horses, people who turned into trees and fortresses that melted away at a magic word. In one adventure, Orlando ran his spear through six enemies at one time. In another, he lost his wits and a friendly knight found them on the moon. Ariosto seemed to be laughing at the old-fashioned tales of chivalry, yet he loved them at the same time that he laughed at them. When his poem was printed, all Italy laughed and loved with him. Four hundred years later, Ariosto’s book was still the Italians’ favourite book of tales. In the practical age of learning and discoveries, there was no place for romantic knights, but people liked to read and remember. They liked to play at holding tournaments and at the splendid, old-fashioned court of Ferrara, the men of the new age could still pretend that chivalry was not quite dead.

Of course, chivalry was dead, or out-of-date. In the Italy where ambitious merchants and condottieri and self-made duke’s fought for cities and fame, a man needed more than a noble title and a well-trained horse to succeed. Ferrara, for its chivalrous ways, was very much up-to-date. The winding streets around the old palaces led to a new part of town whose wide, straight avenues and well-planned houses marked it as the first modern city of Europe. The dukes who ruled Ferrara were not knights, but up-to-date rulers, skilled in the ways of business and diplomacy, poetry and war.

THE DUKE’S SCHOOLMASTER

The Renaissance came to Ferrara about 1425‚ when the old Duke Niccolo III discovered the Romans and the Greeks. Niccolo had worked hard to add to the d’Este family’s power. He had collected towns, stuffed his treasury with gold and built the great Castello. Now he decided that for his children power and wealth were not enough; they must have learning as well. He searched all Europe to find the best possible scholar to tutor his sons and teach Ferrara’s university. Finally he chose Guarino da Verona, a noted professor who had studied Greek in Constantinople. When Guarino moved to Ferrara, students from a dozen cities rushed there to study with him. In winter, they stood in long lines in the snow, waiting to hear his lectures. Old Niccolo was delighted and he was even more pleased with the things Guarino taught his sons. The boys were brimming over with Cicero’s common sense and Plato’s philosophy and all three of them could speak Greek. Niccolo could not understand them when they spoke Greek, but it was enough to know that they could do it.

Niccolo’s boys learned much more than the strange sound of Greek words. With Guarino to guide them, they grew up wise, just and merciful. Each of them in his turn became Duke of Ferrara and in their time the dukedom blossomed with prosperity and splendour. To make room for the hundreds of merchants and craftsmen who came to live in the city, Duke Ercole, the third of Niccolo’s sons, built the new town, nearly doubling the city’s size.

Duke Ercole had six lively children, four boys and two girls. The boys were students, like their father. Alfonso, the eldest, was a solemn youth, concerned with the serious matters of government, war and manufacturing. The courtiers worried that he would make a dull sort of duke, but fortunately he chose as his bride Lucretia, the charming, golden-haired daughter of Pope Alexander VI. When Alfonso did become duke, in 1505, he divided his duties with his wife. While he made himself Europe’s greatest expert on cannon and fortifications, she dealt with the artists and scholars, staged pageants and plays and saw to it that the court of Ferrara was more splendid than ever.

Meanwhile, Duke Ercole’s daughters were fast becoming the most famous women in Italy. For little Beatrice, the youngest child, the castles of Ferrara were fairy-tale palaces where anything she wished for was hers. At five, she was engaged to Lodovico Sforza, the rich ruler of Milan. At sixteen, she married him and went on making wishes — for gowns embroidered with jewels, a court to play with and the title of duchess.

FIRST LADY OF THE WORLD

Her older sister, Isabella, had ambitions, not wishes. Almost from the time that she could walk, Isabella was determined to excel in everything that a noblewoman could be expected to know or do. She learned to write poetry in Italian and essays in Latin, to talk politics with diplomats and painting with artists, to sing and dance and play the clavichord and lute. Visitors to her father’s court came away exclaiming about her brilliance and half a dozen rulers sent their ambassadors to ask the duke to wed her to their sons. Indeed, Lodovico of Milan had asked for Isabella before he asked for Beatrice. When Lodovico sent his message, Isabella had already been promised to Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, the son of the Marquis of Mantua. After all, she was six years old, a ripe old age for the eligible daughter of a duke.

Isabella’s husband-to-be waited ten years for her to reach the age of marriage. By then, he had become the Marquis Gianfrancesco II and Isabella had become a most extraordinary young lady. She rode into Mantua like a queen, followed by 13 huge chests of clothes and cheered by a crowd of 17,000 citizens.

Isabella had grown pretty and she was full of life. She could ride all day and dance all night and never seem tired. She loved clothes and chose them with such fine taste that her gowns set the styles for women in every court in Italy. She seemed to know the right thing to say to everyone –to scholars and diplomats, poets and painters, kings and commoners. Yet she did not hesitate to speak her mind and her sharp wit was a weapon that the courtiers of Mantua quickly learned to fear. She had the boldness of a man, but kept her womanly charm and used both to captivate the great men of Italy. Princes, popes and generals were flattered to be called her friends and a poet named her la prima donna del mondo, the first lady of the world.

Isabella won greater acclaim when her husband was captured in battle and she became the actual ruler of Mantua. When Gianfrancesco came home, after three years in a Venetian prison, everyone rushed to tell him how well his wife had governed his city. Indeed, they repeated their praise so often that Gianfrancesco got rather tired of hearing it. He said so to Isabella and added that he would be grateful if she could act a little less like a ruler and a little more like a wife. Isabella was furious. “Your excellency,” she said, “is indebted to me as never husband was to wife. You could never repay me.”

Gianfrancesco did not try to repay her. He sulked, and Isabella went traveling. Then Gianfrancesco was taken ill and she hurried home. For the rest of his life and during the first years of their son’s reign, she was the actual ruler of Mantua. All Italy knew and praised her. She dealt in diplomacy with the emperor and the king of France and she made state journeys to Rome, where the pope asked her advice. As she grew older, she lost none of her charm, her brilliance, or her tirelessness. At sixty, she could still dance the night through. When she died, at sixty-eight, she was still “the first lady of the world,” the foremost example of the noblewoman of the age, the Renaissance woman.

The pattern for the great men of the Renaissance had also been set in Mantua. Many years before Isabella came there, the city was the home of the “School for Princes” and of Vittorino da Feltre, a schoolmaster whose lessons changed the history of Italy. Vittorino’s employer was the first Marquis of Mantua, his schoolhouse was one of the marquis’ country mansions, his pupils were the marquis’ children and their friends, but his way of teaching was his own. He did not pamper the little noblemen. They were awakened early in the morning, given plain food to eat and forced to study hard — Italian, Latin and Greek, the poetry of Petrarch, Homer and Virgil and the speeches of the Greek orator Demosthenes. They were also taught to play music and to judge paintings. Religious training had an important place in Vittorino’s schedule and there were lessons in conduct. Vittorino expected his students to keep their tempers, to treat each other with respect and to look on lying as the worst sort of crime. In the afternoons, the school moved outdoors for games and sports — wrestling, swimming, running and riding. There was swordplay, too and games of war, for Vittorino never forgot that he was teaching princes, who would one day have to lead their cities in war as well as peace.

Italy had never known a school like this before but Vittorino insisted that his methods were far from new. He was merely copying the ancient Greeks, who had tried to bring up their sons to be “complete men.” Healthy bodies, strong characters and minds full of wisdom, the schoolmaster said, were the Greeks’ goals and his. They were also the goals of the men whom the world would come to call “Renaissance Men,” men who strove to do everything well and came close to succeeding.

Vittorino‘s “School for Princes” grew famous and the heads of many great families begged him to allow their children to attend his classes. For twenty years, he taught as many as he could, the girls as well as the boys. His first pupils began to take their places as the leaders of cities and states and he was pleased when he heard they were governing their people as he had taught them to govern themselves. Some, indeed, were being pointed out as the noblest rulers in Italy.

A WELL-BRED VILLAIN

Learning added to power and wealth did not always bring such happy results, however. A man could use his new knowledge for evil purposes as well as good and Renaissance Italy knew many well-bred villains. None was more famous or hated than Sigismundo Malatesta, who became the lord of a little state called Rimini in 1432. Sigismundo was charming, he read Latin and Greek, he wrote poetry and he was a courageous warrior. He had, in fact, all of the qualities of a good ruler except the wish to be one. His ancestors had all been famous for their double-dealing. Their very name was a warning — in Italian, Malatesta meant “evil head”– and Sigismundo took after his family. His talents and education simply made him a more dangerous villain. He betrayed the cities that hired him to fight as a condottiere and deceived the diplomats who thought they were his friends. Even his poetry served his villainy. Soft verses helped the girls he wooed forget his long hooked nose, his bushy eyebrows, his evil temper. When he had murdered two wives, there was still another lovelorn lady willing to become wife number three.

Under Sigismundo’s rule, the people of Rimini knew only war and misery. When he announced his plan to glorify the city with splendid buildings and art, nobody cheered. New buildings meant new taxes and Rimini was already going hungry. Sigismundo hired Leon Baptista Alberti, the leading architect of the time and asked him to rebuild the cathedral in a Roman style. While the builders worked on the outside of the church, Sigismundo filled the inside with works of art — not madonnas and saints, but statues and paintings of Mars, Saturn, Venus and other pagan gods. The people began to call the cathedral “Temple Malatesta,” because it seemed to have been planned for the glory of Sigismundo instead of the glory of God.

Sigismundo was not much concerned about God. He went to church because he was expected to, but to keep himself amused he sometimes filled the holywater basin with ink and laughed at the people who spattered their Sunday clothes. He also insulted the bishop, defied the pope and conquered several towns that belonged to the church. The pope ignored the insults and defiance, but the loss of his towns was more than he could stand. He issued an order excommunicating Sigismundo from the church. “Of all the men who have ever lived or ever will,” the pope thundered, “Sigismundo is the worst scoundrel, the evil spirit of Italy and the disgrace of our time.”

The journey from Sigismundo’s Rimini to the city called Urbino took less than a day, but life in the two cities could not have been more different if they had been a continent apart. Urbino had the good fortune to be governed by a ruler as noble as Sigismundo was villainous. He was Duke Federigo da Montefeltro, who had been educated at Vittorino’s “School for Princes.”

Duke Federigo said that his teacher had given him “lessons in all human excellence.” The people of Urbino agreed, for the duke was a model ruler. He was kindly and generous to his subjects. Like Sigismundo, he often fought as a condottiere, but he was merciful to his enemies and unfailingly honest with his allies. The money he earned at war he spent to beautify his city and to make Urbino an important center of art and learning. He himself helped to design the new palace, one of Italy’s most handsome buildings. The project in which he took the greatest pride was his library. It included thousands of volumes of history and law, of poetry and music, of religion, mathematics and military tactics, all bound in crimson and silver.

Duke Federigo insisted that the officers and ladies of his court conduct themselves according to the gentlemanly rules of conduct he had learned from Vittorino. He set the example himself and his court became famous for its grace and polished manners. Young noblemen began to turn up in Urbino, asking to be given places in the duke’s army or the staff of his palace in order that they might learn the ways of gentlemanly behavior. The duke, they said, was the noblest commander and most well-bred man in Italy.

When Federigo died, in 1482, his dukedom, court and fame were inherited by his son Guidobaldo. The young duke became the new example of gentlemanliness and his wife, Elisabetta, became the model for the ladies. Elisabetta was the sister-in-law and friend of the great Isabella d’Este, but the two women were nothing alike. Isabella was brilliant, outspoken, and bold. Elisabetta was quiet, soft and gentle. Isabella delighted in pageants and splendid balls at which she could shine before great crowds of people. Elisabetta preferred little gatherings that took place in her drawing room. There a few carefully chosen ladies and gentlemen would meet in the evenings to play music and sing, to dance and especially to talk — of philosophy and love, of art and poetry and of the ways of courtly life.

RULES FOR GENTLEMEN

One of the regular guests at these meetings was a young nobleman, Baldassare Castiglione, who had come to Urbino hoping to win glory as an officer in the duke’s army. Instead, he had broken his ankle and had been sent to the palace to recover. He stayed for eleven years. When he finally went away, the delights of Urbino’s graceful, well-bred court were so much in his mind that he wrote a book about them. He called it The Book of the Courtier, though he might well have called it How to be a Gentleman. He wrote about a long imaginary conversation in which Elisabetta and her friends talked about the qualities that made a man a gentleman. Castiglione felt that a gentleman ought, first of all, to be of noble birth, but he did not insist on that. After all, one of Elisabetta’s friends was a Medici, whose family had no noble title and she much admired the Sforzas of Milan, whose titles were borrowed at best. About everything else, however, Castiglione was quite certain. A gentleman, he said, must be skillful in war, expert at riding, fencing‚ swimming, jumping, running and other sports. Tennis, he suggested, was a sport particularly suited to the gentleman. He warned that a gentleman should never be so expert at such things that people could say he was showing off. In fact, the mark of a true gentleman was that he did everything perfectly, gracefully, but with no sign of effort.

Of course, Castiglione said, the ideal gentleman must be learned. He must understand Greek and Latin, know poetry, history, speak and write well. It was an excellent thing, too, if he could write songs and please the ladies by singing them well. The ladies, indeed, were most important: “No court, however great it may be, can have any beauty or brightness in it, or any mirth, without women, . . . nor can a gentleman be gracious, pleasant, or brave . . . unless he is stirred with the conversation and love of women.”

Castiglione also set out rules for the ladies to follow. They must be gracious, learned and polite. They must have clothes that are fashionable without being gaudy, a talent for music, verse and above all else, gentle tongues.

When Castiglione’s book was published, in 1528, it became the guidebook for would-be gentlemen in every city in Italy. It was translated into French and English, people all over Europe rushed to buy it. They practiced tennis anxiously, hired new tailors, took music lessons and in the privacy of their bedchambers struggled to write verses — and, of course, they tried to pretend that none of this was any effort at all. Vittorino’s ideas about the training of noblemen had traveled far from the little school in Mantua. Indeed, they had become a strict code of conduct for the new age, a code which the gentlemen of the Renaissance could follow as the knights had once followed the code of chivalry.

Yet even before Castiglione’s book was printed, Urbino, the home of model gentlemen, was conquered, sacked and Guidobaldo and Elisabetta were forced to flee to Venice. The stories of many of Italy’s ruling families ended with defeat and flight, or destruction and death. Their cities were too rich and too small. Their bigger neighbours fought over them and foreign invaders overran them. In Ferrara, Boiardo stopped telling his tales of chivalry and wrote instead, “I see all Italy in flame and fire.” In Mantua, Isabella d’Este gave her last years to a desperate struggle to save her city. Some Italians said that Italy could only survive if it had princes who were strong, cunning and cruel — princes for whom nothing mattered but power. In Florence, about 1513, a man called Machiavelli began to write a book of rules and instructions for the princes whose power might save Italy.

Niccolo Machiavelli was an unlikely man to talk to princes. He was a commoner, a courtier without a court, a diplomat whose cunning no one wanted to employ. Politics was Machiavelli’s life. For fourteen years he had been an officer in the government of the Republic of Florence. He had traveled on state business to the courts of the emperor and the king of France and had been at home in the palaces and military headquarters of the most powerful men in Italy. Then the Medici had returned, aided by a Spanish army and the pope. Suddenly Machiavelli was a nobody, or worse than a nobody, for he was a citizen out of favor with the rulers of his city. He went to live on the little country estate that belonged to his father. By day, he played the country gentleman, but at night he lived again in the world of diplomats and kings.

RULES FOR PRINCES

He turned to writing, and, at first, he wrote about governments of the people, republics, that would give Italy the strength that it had had in the days when the Republic of Rome conquered the ancient world. Later, as he saw the states of Italy feuding and growing weak, he changed his mind. Italy could only be saved, he decided, by a monarch strong enough to hammer all those little states into a single mighty power. So he wrote the book he called The Prince. Like Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, The Prince was a guidebook for ambitious men. Machiavelli’s rules for princes were very different from those by which the gentle, well-bred courtiers lived.

“It is not necessary for a prince to be merciful, faithful, sincere or religious,” Machiavelli wrote, “for that would make him dangerously weak. It is most necessary for him to seem to be these things.” A prince, he said, must pass for good, but “know how to do wrong when it is necessary. . . He must know how and when to lie and he must be able to do it well . . . He should have but one object, one art: the art of war . . . He must be both a lion and a fox — a lion in order to frighten the men about him and a fox in order to avoid their plots.”

A man of power, ruthless, cruel and sly — such a man, Machiavelli thought, could succeed where generous, plain-dealing men like the dukes of Urbino had failed. It was useful, of couse, if a prince through his shows of goodness could win his people’s loyalty and love. “The best possible fortress,” Machiavelli said, “is to avoid the hatred of your subjects.” That was rarely possible, and “it is far safer to be feared than loved . . . Men in general are ungrateful, fickle liars . . . As long as you give them what they want, they will promise you anything: their blood, their gold, their lives‚ or their children . . . But when you begin to ask instead of to give, they will revolt . . . All men are bad and ready to show their evil natures when they have the chance . . . You can put no faith in their pretended love . . . Fear never fails.”

Few men had ever spoken so harshly of mankind and none had called treachery a good thing in a king. When people read Machiavelli’s book, they forgot that his prince, the conqueror who could trample over men and cities and feel nothing but scorn, was meant to be the saviour of Italy, the leader in the battle for independence. They remembered only that the book taught the art of tyranny and they made Machiavelli’s name another word for villain. Throughout Europe, schemers who plotted for power came to be called “Machiavellis.”

Machiavelli had not invented the ruthless system of ruling that he wrote about. Like Castiglione, he had merely described what he had seen in Italy in his own time. Castiglione had known the bright und splendid side of the Renaissance men. Machiavelli peered into the dark corners of their souls and he saw the ugliness and greed that came with the riches, the love of beauty, learning and the ceaseless fight for fame. If he talked of rulers whose methods were fear and treachery, it was because he had seen such methods used.

The Prince was not a portrait of an actual ruler, for Machiavelli knew of no one who used his princely methods perfectly. One man, however, did come close. He was Cesare Borgia, a brilliant and successful young general.

“DO WHAT YOU MUST”

Cesare Borgia was all that a gentleman should be. He was handsome, intelligent, witty, gracious and well-bred. Of course, there were those who said that he had murdered his brother and others who feared he was more cruel than clever. Machiavelli saw in him the mark of a true prince — the will to power. He had been named for Caesar and on the blade of his sword was the motto, “Either Caesar or no one.” On his ring were carved the words, “Do what you must, come what may.”

Young Cesare’s father was the pope, who hoped to make a Borgia dukedom of the states that belonged to the church. Cesare, of course, was to be the duke. By 1502, when he was twenty-seven, Cesare had overthrown a dozen rulers and taken over the governing of their cities. He had made himself the most successful condottiere in Italy and proved himself a talented schemer and teller of lies. He had courted the friendship of the duke and duchess of Urbino until he won their trust; then he had borrowed their cannon and used it to help him conquer their city. Later, with the neatest piece of diplomatic trickery that Italy had seen in years, he outwitted a group of noblemen who conspired to murder him.

The conspirators were all officers, old hands at plots and counterplots. One was famous for having won control of his city by entertaining its leaders at a well-poisoned banquet. Yet Cesare so charmed them with his offers of good will that they called off their plan to kill him. They even agreed to leave their soldiers behind when they came to his castle for a friendly conference. The meeting turned out to be a brief one: Cesare had them strangled.

Machiavelli had had a first-hand view of his triumph, for it occurred while he was at the castle as an ambassador from Florence. He described it in great detail in his book, as an example for ambitious princes. He agreed with the king of France, who sent word to Cesare that it “was a deed worthy of the great days of ancient Rome.”

Machiavelli could not write a happy ending to the story of his promising prince. Cesare’s right to hold his conquered cities depended on his father’s power over them as pope. When his father died and a new pope took his place, a pope who was the Borgias’ bitter enemy, Cesare’s empire of cities “vanished as the smoke in the air, or the foam upon the water.” He called for the help of the allies he had courted with favours, promises and gifts. None of them came to his aid. As Machiavelli pointed out, when a prince loses his power and begins asking instead of giving, he has no friends. Even Cesare’s troops deserted him. At last, he stood on a battlefield with only one companion and fought on until he was killed.

No other Machiavellian prince appeared in Italy. Instead, the job of uniting the states and little towns of the peninsula fell to the popes. For a time, they led the fight for Italian liberty.

In the rest of Europe, however, men who dreamed of power eagerly studied the little book that promised to teach them how to win and hold a kingdom. These men who followed the harsh code of the prince took their places beside the gentlemen who lived by the code of the courtier.